Enigmatic (Book Three, Part 47: Fear and Loathing, The Simple Art of Murder)

Previously in The Last War in Albion: Garth Ennis was eventually joined on Hellblazer by Steve Dillon, whose simple expressiveness was a perfect fit for Ennis’s style, and who would go on to be the most significant collaborator of Ennis’s career.

“Yeah, well, that’s me, ennit? Enigmatic.” – Grant Morrison, Hellblazer

This arc wrapped in November of 1992, and with the arrival of Vertigo on the horizon Ennis wisely decided to do a pair of one-offs. The first of these saw him return to Constantine’s family with a story about his niece Gemma unwisely deciding to begin playing with the occult. This mostly served as a small showcase for Kit, who gets a four page scene in which she tries to talk Gemma out of continuing with the occult, noting her firm rule that Constantine keep his occult life away from hers, pointing out how “he’s been all over the world, he’s seen incredible stuff, he’s had the time of his life, and he’s cause a terrible, terrible lot of pain while he’s been at it,” and finally suggesting that the next time someone messes with Gemma she should just “chin the wee bitch,” It’s a succinct demonstration of the character, perfectly capturing why she’s an interesting counterpart to Constantine.

For his first Vertigo issue, meanwhile, Ennis penned a comedy issue about John Constantine’s surprise fortieth birthday party, thrown for him by the Lord of the Dance with a cross-section of Constantine’s supporting cast attending. This allows Ennis a change of gears, demonstrating the basic fact that he can do comedy. And indeed, the issue is tremendously funny, taking advantage of the oddity of the transition to use the permissiveness of Vertigo, which would soon become a siloed entity, to comment on the DC Universe it was in the midst of parting from. And so Ennis pulls gags like having the Phantom Stranger visit Constantine while he’s outside taking a piss, causing Constantine to surprisedly turn and pee on the Stranger’s shoes. “I had hoped we could ignore the cold facade that our kind deems so necessary, if only at this time of celebration. But I see there will be no hands clasped against the dark this night. I see I must remain a stranger,” he intones with sublime pretension before vanishing into the night. The issue is a charming bit of irreverence, if a stange sales pitch for Ennis’s run. Nevertheless, it worked; as Ennis describes it, the Vertigo launch meant that “The sales tripled… Just for one issue because there was a massive publicity push, which died away instantly the next issue, but it did us a lot of good. Even when the sales died down again they were still not quite double what they had been, so that was pretty good. A bigger audience got into Vertigo, and into that kind of comic.”

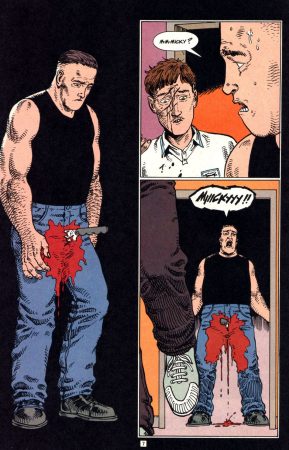

The first proper arc to take advantage of the book’s newfound readership was Fear and Loathing, which saw Ennis return to one of Jamie Delano’s best tricks, albeit with his own distinct spin on it. The story saw Constantine hunted by Charles Patterson, the white supremacist he briefly encountered all the way back in Dangerous Habits when visiting the archangel Gabriel at the Cambridge club. This was the same basic trick—putting Constantine up against an entirely mortal and mundane threat—that Delano used to great effect when having Constantine hunted by the serial killer known as the Family Man. But where that story was entirely grounded in the human scale, featuring no supernatural elements at all, Fear and Loathing splits its attention. Charles Patterson uses entirely non-magical means in hunting Constantine, and his defeat similarly comes not as a result of any of Constantine’s magic but because the brother of a Black man that Patterson killed earlier in the arc blows his head off with a shotgun. But all of this plays out over a b-story in which Gabriel suddenly walks out of the Cambridge club and begins to wander London, eventually falling in love with a woman. This only directly connects to the other plot at the outset; Gabriel’s departure is prompted by his doubts and concerns over Constantine pointing out that one of his associates is a neo-nazi, and in turn prompts Patterson, who was grooming Gabriel as an ally, to begin his hunt of Constantine. Beyond that the plots play out in parallel, not even really converging at the end.

Within the Gabriel plot the key revelation is that the woman is in fact a disguised Ellie, who is working on Constantine’s behalf to trick the angel into falling so that he could gain leverage over him to use against the First of the Fallen. This succeeds, and the arc ends with Gabriel wandering the streets, his back a bloody mess from where Constantine cut his wings off with a chainsaw. Impressively, however, this is by some margin the less significant ramification of the arc. The more important development came in the mundane plot, when Patterson attempts to get at Constantine by sending some heavies to attack Kit. Ennis uses this development to subvert the “women in refrigerators” trope, having Kit handily dispatch the goons, grabbing a chef’s knife and driving it into one’s crotch before clawing the other in the face. Despite the ease with which she handles the problem, however, Kit is deeply traumatized by the attack and blames Constantine for breaking his promise not to get her involved in his crap (the bitter irony being that it wasn’t even the magical side of his life that got her in trouble) and leaves him, sending Constantine into a drunk and depressive spiral.

The broad take on Constantine’s character represented here reveals a deeper set of roots in noir than simply adopting the prose techniques of people like Elmore Leonard to comics. In this regard it is helpful to turn to Raymond Chandler’s 1950 essay “The Simple Art of Murder,” which serves as a sort of manifesto for the style, albeit one written after the bulk of its greatest works were already completed. Nevertheless, Chandler was one of its great early practitioners, following from the earlier work of Dashiell Hammett to create Philip Marlowe, the archetypal hardboiled private investigator.

Much of “The Simple Art of Murder” is framed as a critique, establishing the distinctions between Chandler’s preferred style of detective story and what he describes as “the English formula.” Chandler’s account of this is deliciously sneering, describing how “old ladies jostle each other at the mystery shelf to grab off some item of the same vintage with a title like The Triple Petunia Murder Case, or Inspector Pinchbottle to the Rescue” and describing the plots as “futzing around with timetables and bits of charred paper and who trampled the jolly old flowering arbutus under the library window.” He singles out the great masters of the form for absolutely savage insults; Arthur Conan Doyle’s corpus is summarized as “mostly an attitude and a few dozen lines of unforgettable dialogue,” the resolution of Agatha Christie’s Murder on the Orient Express dismissed as “guaranteed to knock the keenest mind for a loop. Only a halfwit could guess it,” and The Red House Mystery is subjected to a ten paragraph flensing of such comprehensive brutality it’s a wonder A.A. Milne survived all the way to 1956. Having so massacred the entire literary tradition of British detective fiction he casually delivers the coup de grace, declaring that “The English may not always be the best writers in the world, but they are incomparably the best dull writers.”

Chandler, meanwhile, starts from the premise—not entirely justified, but embraced with such passion as to render that irrelevant, that “Fiction in any form has always intended to be realistic.” And so he roots his own vision of detective fiction in the reality of murders and their investigations, noting how writers of the English style imagine that “a complicated murder scheme which baffles the lazy reader, who won’t be bothered itemizing the details, will also baffle the police, whose business is with details. The boys with their feet on the desks know that the easiest murder case in the world to break is the one somebody tried to get very cute with; the one that really bothers them is the murder somebody only thought of two minutes before he pulled it off.” In his view, the failure to start from these material truths leads to a larger failure at having anything to say. As he puts it, “if the writers of this fiction wrote about the kind of murders that happen, they would also have to write about the authentic flavor of life as it is lived. And since they cannot do that, they pretend that what they do is what should be done.”

And so he turns to Dashiell Hammett, his fellow great noir writer, whose style he followed in. Hammett, he explains, “ gave murder back to the kind of people that commit it for reasons, not just to provide a corpse; and with the means at hand, not with hand-wrought duelling pistols, curare, and tropical fish. He put these people down on paper as they are, and he made them talk and think in the language they customarily used for these purposes.” There is, to be sure, a direct line from this to the simple and unfussed prose of Elmore Leonard. But Chandler builds a larger aesthetic edifice out of all of this, noting that Hammett’s fidelity to actual human speech provided the foundation for a larger honesty in the depiction of the world at large, depicting “world in which gangsters can rule nations and almost rule cities, in which hotels and apartment houses and celebrated restaurants are owned by men who made their money out of brothels, in which a screen star can be the fingerman for a mob, and the nice man down the hall is a boss of the numbers racket; a world where a judge with a cellar full of bootleg liquor can send a man to jail for having a pint in his pocket, where the mayor of your town may have condoned murder as an instrument of moneymaking, where no man can walk down a dark street in safety because law and order are things we talk about but refrain from practising; a world where you may witness a hold-up in broad daylight and see who did it, but you will fade quickly back into the crowd rather than tell anyone, because the hold-up men may have friends with long guns, or the police may not like your testimony, and in any case the shyster for the defense will be allowed to abuse and vilify you in open court, before a jury of selected morons, without any but the most perfunctory interference from a political judge. It is not a very fragrant world, but it is the world you live in.”

From here, Chandler comes to the essay’s concluding and most famous passage, in which he describes the classical noir protagonist. “down these mean streets a man must go who is not himself mean, who is neither tarnished nor afraid. The detective in this kind of story must be such a man. He is the hero, he is everything. He must be a complete man and a common man and yet an unusual man. He must be, to use a rather weathered phrase, a man of honor, by instinct, by inevitability, without thought of it, and certainly without saying it. He must be the best man in his world and a good enough man for any world. I do not care much about his private life; he is neither a eunuch nor a satyr; I think he might seduce a duchess and I am quite sure he would not spoil a virgin; if he is a man of honor in one thing, he is that in all things. He is a relatively poor man, or he would not be a detective at all. He is a common man or he could not go among common people. He has a sense of character, or he would not know his job. He will take no man’s money dishonestly and no man’s insolence without a due and dispassionate revenge. He is a lonely man and his pride is that you will treat him as a proud man or be very sorry you ever saw him. He talks as the man of his age talks, that is, with rude wit, a lively sense of the grotesque, a disgust for sham, and a contempt for pettiness.” It will not go unnoticed that many parts of this double neatly as descriptions of John Constantine, at least as he’s written by Ennis. Constantine is, in this era, very much the good man in a bad world, with a similar sense of being an honorable loner. Certainly some details fail to match—most obviously in Chandler’s description of sexual morality; Ennis mercifully has no interest one way or the other in protecting the fragile honor of virgins.

In his introduction to the trade paperback of Fear and Loathing Warren Ellis makes a case much like this only to ultimately dismiss it. Constantine, he notes, is “Frequently painted as a mystic investigator in some kind of bastardized Chandlerian tradition, Society’s Knight riding against the Bad Craziness in the dark,” when in fact Constantine is “Society’s Bastard, locked inside the world he hates, angry and twisted, holding a small, poisoned set of ethics to his chest. And that last point is possibly the only thing that really makes him different from the rest of them. That’s what makes him wake with anger and lie down with it. That little voice that says Fucking People Over Is Wrong, and No One Else Should Have To Live Like This.” Ellis is a savvy enough critic that this must be taken seriously in spite of his obvious deficiencies as an expert on not fucking people over. And yet something about his analysis remains unsatisfying.

June 7, 2022 @ 1:15 pm

This is a great side trip, connecting some of my favorite genre’s: 90’s Comics & Noir Fiction. I really appreciated this installment. And an Elmore Leonard reference to boot!