Fantasy Means Almost Nothing (Book Three, Part 64: Real War Stories)

Before we get started, an update: my new Patreon, which I had to start from scratch after Patreon informed me that it was not possible to simply convert my Patreon of nine years over to per-month billing, is still $2400 a month short of the old one, which is an absolutely terrifying hit to my income. This new Patreon gives you more content—all my ebooks, Britain a Prophecy, and more—for less money than the old one, and if you want my work to continue I really implore you to support it.

Especially because, as of a few minutes ago, all Patrons got access to a pre-release ebook of Last War in Albion Volume 3, featuring this amazing cover.

So if you’re not currently a supporter of my work on Patreon, please do consider changing that.

Previously in The Last War in Albion: Having finished his outstanding obligations to DC and free at last to pursue his own interests, Alan Moore moved on to other things.

There are things that happen out on the most violent edge of human experience that eclipse fiction by their sheer intensity – that you simply could not ever invent. The many accounts I’ve read of human experience in wartime reveal degrees of courage, cruelty, cowardice and even kindness that are beyond imagination. Next to that, fantasy means almost nothing. – Garth Ennis, interview with Unwinnable

One of the first of these things would see Alan Moore make his final trip to the United States in October of 1987, a few months after the publication of Watchmen #12. Although he was still a couple of months away from finishing his work on V for Vendetta, he did not visit the DC offices at all. Instead he went to Washington DC, where he met with members of a law firm called the Chrsitic Institute and with the American comics writer Joyce Brabner.

Moore had already worked with Brabner before on a volume called Real War Stories, published by Eclipse Comics the same month that Watchmen and Swamp Thing concluded. This was a comic produced with the Central Committee for Conscientious Objectors, which, as Brabner explained it, “needed a tool to reach teenagers with information about the military. This was during the peacetime draft, when they were looking for smart white kids to sign up, and they had a very aggressive recruiting campaign around the time Top Gun was in the theatres.” The CCCO had originally envisioned and had the budget for a small indie book, but Brabner successfully argued that in order to have any impact on its intended audience “it had to be a color book with popular artists and writers if we were going to get the kids,” and so she worked with Eclipse Comics to bring the project to fruition. Moore’s explanation for his interest in the project, printed (along with similar statements from other contributors) at the outset of the comic, was simple: “Because I have a deep aversion to all forms of violence and war, and if I have to explain, I must fall back on the pacifist slogan that says ‘A bayonet is an instrument with a worker on either end of it.’” And he was part of an impressive roster of talent including Denny O’Neil, Brian Bolland, Bill Sienkiewicz, Mike Barr, and much of the Swamp Thing team with Stan Woch, John Totleben, and Steve Bissette all joining him on his story, entitled “Tapestries.”

The basic structure of Real War Stories was exactly what its title implied: in contrast to countless war books offering jingoistic stories of adventure and daring, this book would offer actual stories about war. This meant that the various writers and artists were paired with veterans whose experiences had led them to rethink war and militarism and tasked with telling their stories. In Moore’s case, this meant W.D. Ehrhart, a poet and memorist. Moore’s work is based both on conversation with him and on his memoirs, which are in places adapted quite closely. The second chapter of Ehrhart’s memoir Vietnam-Perkasie: A Combat Marine Memoir, for instance, began, “I grew up in Perkasie, Pennsylvania, a small town between Philadelphia and Allentown. By the time I graduated from high school, Perkasie was beginning to show a terminal suburban sprawl, but when I was growing up it was still just a quiet little country town. People left their houses unlocked at night, neighbors called to each other from large front porches on warm summer evenings, and kids went sledding on Third Street hill when it snowed in the winter. There were no traffic lights in town. The whole countryside around was dotted with small family farms, and you could get on your bicycle and in ten minutes be caosting between cornfields, or go down to Lake Lenape and catch painted turtles and water snakes. Carolers strolled from house to house on Christmas Eve, and Jimmy the shoe repairman knew the shoe size of everyone in town.” Moore’s adaptation, meanwhile, has Stan Woch drawing a young Ehrhart atop his bike on an idyllic suburban street, with a caption explaining, “I grew up in Perkasie, Pennsylvania, where the shoe repairman knew the sizes of everyone in town.”

Moore, however, is not acting as a mere summarist of Ehrhart’s work, even as he draws quite directly from his prose. Moore instead adopts a non-chronological storytelling approach similar to what he did in the “Watchmaker” chapter of Watchmen, albeit with less jumping around. His pages are arranged in asymmetrical six panel grids, two panels to a row, with one narrative timeline running down the left side of the page, the other down the right. So at the start the panel of Ehrhart and his bicycle fondly remembering the memorious shoe repairman is juxtaposed by a second panel describing Ehrhart at boot camp “sick-scared, emptying our pockets beneath naked limbs, deafened by drill sergeants” yelling offensive slurs at them. The third panel then jumps back to Ehrhart’s childhood memories of saying the Lord’s Prayer and the Pledge of Allegiance and doing atomic bomb drills at school, and then the fourth goes to Vietnam, where Ehrhart recalls “collecting Civilian detianees, temporarily held for questioning… mostly old men, women, and children. Bound hand and foot with wire they’re thrown over the tractor sides and stacked like cord wood. I hear bones breaking.”

“Tapestries” is divided into two parts, a three-page first installment with art by Woch and Totleben, and a four-page second part with Bissette on art. In the first part, the two timelines move linearly: the left side of the pages move from childhood memories up to Ehrhart leaving for boot camp, while the right side begins precisely where the left leaves off, with Ehrhart at boot camp, and continues through his war experience and into his difficult reintegration into civilian life. Interestingly, the two sides are narrated in different tenses—the left-hand panels are told in the past tense, while the right-hand side is told in the present tense.

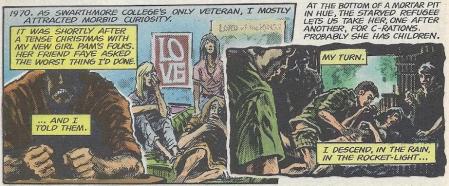

The second part of “Tapestries,” meanwhile, inverts the paradigm slightly. The left hand panels essentially begin where the right-hand of part one left off, in 1968 with Ehrhart back in Perksie, drunk and throwing up in the men’s room feeling “lonely and used. I feel defiled.” Part two picks up with a left-hand panel set in 1970 with Erhart at Swarthmore College, recalling how his girlfriend’s “friend Faye asked the worst thing I’d done. And I told them.” The right-hand panel then offers a flashback to the war, with Ehrhart remembering how “At the bottom of a mortar pit in Hue, the starved refugee lets us take her, one after another, for c-rations. Probably she has children. My turn.” Notably, even though these right-hand panels are now taking place at an earlier point in Ehrhart’s life than the left-hand panels, it is still narrated in the present tense while the narrative of Ehrhart’s life in Swarthmore and beyond is in the past tense, giving the war memories status as traumatic events existing in an eternally re-experienced present—a point emphasized by the fact that several of the events recalled in this portion of “Tapestries” are second tellings of things that already appeared in the first part. The effect is a strangely elliptical, lyrical story about trauma, the wreckage of naive beliefs, and growing up—a quietly powerful comic, if not quite an arresting counter-narrative to Top Gun.

While it’s not entirely clear what direct impact Real War Stories had, it was at least enough to irritate the US Department of Defense. Brabner recounts the comic being distributed at a high school career fair in Atlanta, where it sparked controversy with a local newspaper who “lashed out at the presence of Real War Stories and related material at the school, saying there was no such thing as a career in peace in America.” This sparked a pressure campaign that led to the school removing the CCCO from the career fair, which prompted a lawsuit, to which the Department of Defense sent a expert witness named who attempted to attack the credibility of the comic, taking particular issue with the opening story, by Mike Barr and Brian Bolland, which related the experiences of Tim Merrill, a Navy sonar technician turned conscientious objector. This story depicted the practice of “greasing,” a hazing ritual in which new recruits are anally penetrated by a grease gun. As Brabner tells it, “We had military Naval court records on hand involving a female recruit who had this happen, and in court it had been established that this was a military tradition!” The Department of Defense went home with its tail between its legs, and quickly withdrew their objections to the book.

A second issue of Real War Stories followed in 1991, this time seeing Brabner work with Citizen Soldier, another anti-war veterans group. This was a slightly less impressive package, although Mike Barr and Bill Sienkiewicz still contributed, along with Oracle co-creator Kim Yale, but it continued in the vein of socially conscious comics as journalism that were quickly becoming Joyce Brabner’s niche—a niche that would soon see her working together with Moore again, this time on a far larger and more ambitious project.

Brabner describes her route into the comics industry thusly: “How did I get into comics? I became a character in one.” Although straightforward, this description raises a lot of questions, most of which are answered by the fact that the comic in question was Harvey Pekar’s American Splendor. Pekar had come up as a writer in the underground comix scene, having become friends with Robert Crumb after meeting him at a swap meet in Cleveland, Ohio, where they were both looking for jazz records. Pekar remained friends with Crumb, and in 1972, while Crumb was visiting Pekar, Pekar presented him with stick figure layouts for some comics of his own, and Crumb was sufficiently impressed to agree to illustrate one of the strips, which appeared that year in his anthology The People’s Comics. This was a one page strip entitled “Crazy Ed,” in which Pekar is introduced to the eponymous Crazy Ed, who tells a go-nowhere anecdote about another guy named “Horvee” he knew once. When the anecdote comes to its non-ending, Pekar expresses a panel of confusion, then turns to the reader to grin and exclaim, “Wotta demon!”

This was indicative of Pekar’s basic style, which was to tell autobiographical, observational vignettes about his life in Cleveland as a file clerk at the VA hospital. Over the next four more years he did a couple more stories in various underground magazines before, but he grew frustrated because, as he put it, “the counterculture which had supported alternative comics was dying out. A lot of these middle-class kids who were part of the counterculture—as soon as they found out they weren’t going to be drafted, that they didn’t have to go to Vietnam—they just went on and became ‘straight’ again. As a result, the alternative comics just didn’t have much of an audience anymore. It was becoming difficult for me to get my stories published.” And so Pekar set his record collecting hobby aside for a while and saved up the money to self-publish his own comic, called American Splendor, a name he described as “kind of ironic… because most people would not think of my life as very splendid!”

The first issue of American Splendor opened with a two-page piece entitled “A Fantasy” that offered an embellished version of R. Crumb’s 1972 visit to Cleveland, this time featuring Harvey Pekar angrily laying into Crumb, berating him for not getting in touch for a year and a half, and shouting “I oughta wring yer skinny neck! Whadaya think, yer too good for yer buddies in Cleveland?!” before cajoling him into drawing some of Pekar’s comics, insisting that Crumb, as a “lousy schmuck” who’s “over the hill,” would benefit from working with a hot new talent like Pekar with his “new neo-realist style.” A browbeaten Crumb acquiesces to a two-pager, which is, of course, the very strip this is all depicted in. (Crumb, for better or for worse, was content to print the legend on this, telling an interviewer that Pekar “would have been totally happy if I just completely dedicated myself to drawing his comics and nothing else. He had a big ego, and he didn’t care if I continued to draw my own stuff or not. And in order to persuade me to draw his comics he would tell me, ‘Aw Crumb, you’re all washed-up; you’re finished. It’s over for you. You should get on the bandwagon with my stuff — my stuff is really what’s happening. My stuff is the hottest thing.’ [laughs] Yeah, I liked drawing his stuff, ‘cuz it was good, you know, story and dialog, but I didn’t want to spend all of my time just drawing his stuff. So, he very quickly realized that and got other artists to draw his stuff too.”) [continued]