Hey, Did You Hear The One About The Nuns? (The Last War in Albion Book Two Part Twenty-Seven: Nemesis)

|

| Figure 938: Miracleman throws a car full of people at Kid Miracleman. (Written by Alan Moore, art by John Totleben, from Miracleman #15, 1988) |

Previously in The Last War in Albion: Coming to the end of his run on Miracleman, Moore decided to grapple with as brutally realistic a portrayal of a superhero fight as he could imagine – to actually show what such a battle would mean for the world in which it took place.

Moore had grappled with some of this in the first Miracleman/Kid Miracleman fight when, for instance, Kid Miracleman hurls a baby through the air in the middle of the fight, distracting Miracleman by throwing a baby at a nearby building, which Miracleman of course saves, but with the note that he’s broken a couple of the baby’s ribs because of the speed he was traveling, a grimly funny note of realism in a standard superhero trope. There’s a not entirely dissimilar moment in Miracleman #15 when Miracleman, in another fairly standard superhero punch-up moment, picks up a car and throws it at Kid Miracleman. “My apologists have claimed the car that I first hurled at Bates was empty, those who’d been inside having all previously escaped,” he narrates. “I’m sorry, but that isn’t true,” the final caption box changing color to be yellow on black – Bates’s colors. The shift in tone – from a winking subversion of the “superheroes save everybody” to a stark-faced refusal to offer any sort of salvation at all – is stunning.

And this is hardly the only such moment in Miracleman #15, an issue that returns over and over again to images of stark brutality. Kid Miracleman, under Moore, had always been portrayed as a brutally sadistic figure, whether in his mocking murder of his secretary in his first appearance “just to show you that I don’t mind doing that sort of thing. In fact, I quite enjoy it” or in his dispatching of the nurse in Miracleman #14. But what is striking – especially for Moore – is that the issue contains almost no textual descriptions of what Kid Miracleman does to London. Early on the narration establishes that Bates spends hours in London before Miracleman and company realize he’s back, and talks about “those hours that he had crammed with centuries of human suffering; those narrow side-streets filled with miles of pain. Having exhausted all the humdrum cruelties known to man quite early in the afternoon he had progressed to innovations unmistakably his own,” and the end narration makes a fleeting and bleak mention of “coral reefs of baby skulls, and worse,” but this is the extent to which Moore uses the written word to frame these depravities into the sort of classic and endlessly quotable lines that had characterized, for instance, Rorschach’s famously bleak narration in Watchmen. There are neither “abattoirs of retarded children” nor “gutters full of blood” to drown the vermin in.

|

| Figure 939: John Totleben’s double page spread of utter carnage. (Written by Alan Moore, from Miracleman #15, 1988) |

Instead there is John Totleben’s art, at once scratchy and meticulous, with an almost fractal density of hatching, like a woodcutting of a charnal house. The issue’s most acclaimed beat is a double page splash at the end, after Kid Miracleman has been defeated, that simply shows the devastation wrought by both the battle and by Bates himself. On the one hand it is a familiar and popular bit of 80s comic book stylistics – the sort of intricately detailed spread that characterizes, for instance, George Pérez’s work. But instead of the appealingly bright and clean tableaus of Crisis on Infinite Earths, where, for all the nominally apocalyptic tone, the pleasure was always firmly pouring over the page and identifying the heroes, both obscure and iconic, tucked into every nook of the page, Totleben’s spread is one of pure and unrelenting horror. Its centerpiece is a twisted and bent lamppost from which two bodies hang, wrapped in barbed wire. A severed head is impaled upon the lamppost’s spire, bent sideways. To its right, a woman, her dress in shreds, screams. Her eyes are empty sockets; her children cling to the bloody stumps that were once her arms. In the foreground, three bodies are slumped together. A spike runs through two of their heads. But these are only the most emphasized parts of the tableau. The meticulously restored version eventually published by Marvel, recolored by Steve Oliff emphasizes the scale best – countless twisted and mangled corpses, dismembered by the burning ruins of London in which they are scattered, and a handful of shellshocked, stunned survivors stumbling through it. Even in the original Eclipse version, colored by Sam Parsons, the horror is inescapable, a ruined city lit by the flames of the burning Houses of Parliament in the background, everything suffused in a haunting and sickly green.

|

| Figure 940: Plate 41 of Goya’s Disasters of War |

This, however, is only the largest and loudest piece of horror in the issue. From the close-up of Bates’s head after the Warpsmith Aza Chorn teleports a chunk of concrete and rebar into the middle of his skull is one of of sheer brutality, as is the haunting opening image of a clothesline upon which three human skins have been hung, legs twisting in the breeze, rictus and hollow anguish on their faces, or the hands of Big Ben, or simply the myriad images of people running, desperately and futilely trying to flee the cityscape of raw carnage. Totleben has spoken about how he “wanted it to look more like Goya’s Disasters of War or Mathew Brady’s Civil War photographs where you just see the bodies laying all over the fields,” and the contrast between this and usual styles of superhero art is vast, rendering Miracleman #15 less an exploration of sadistic violence (indeed its detached excess means that no individual act of violence is particularly lingered upon in the same way as, for instance, the murder of Stephanie back at the beginning of the run, with its narration of “her name is Stephanie. She likes Adam and the Ants. Her boyfriends name is Brian. She collects Wedgwood. Her insides have turned to water” and Kid Miracleman’s sadistic quip of “you dropped the coffee, Stephanie. You dropped the coffee!” as he kills her) than a demonstration of an absolute conceptual limit – the furthest that the idea of superheroes as, to quote Moore in an early issue of Swamp Thing, “Over-People” can be pushed. Or so he thought.

In some ways there is no better encapsulation of the inconsistent nature of Moore’s aesthetic influence and success in the 1980s than the fact that, between issues #9 and #15 of Miracleman, it is the latter that has had almost all of the visible impact on the development of superhero comics. In reality it is “Scenes from a Nativity,” with its six panels of reverential but detailed depiction of a woman giving birth, that represents an aesthetic endpoint – a line that no mainstream American comics have ever surpassed, or even really approached, while the smoldering piles of twisted bodies in issue #15 have seen so many imitators that it is depressingly easy to miss what was so chilling and powerful about the comic when it came out in late 1988. (Certainly Moore has expressed dismay about it on many occasions.) But contextualizing the end of Miracleman with the rest of Moore’s 80s superhero work requires going beyond issue #15. That issue, after all, ends with the note that “in all the history of Earth there’s never been a heaven; never been a house of gods that was not built on human bones,” a sentiment that almost perfectly matches Rorschach’s final observation that “one more body amongst foundations makes little difference” in the grand scheme of Ozymandias’s newly forged utopia. But where Watchmen ends on a note of meticulously constructed ambiguity, with the fate of the impending utopia delicately balanced in the ketchup-stained hands of Seymour, Moore’s Miracleman run spends its entire final issue exploring the post-superhuman world.

What is striking about Miracleman #16, and indeed about the resolution of Watchmen as well, is the depth of ambivalence displayed towards utopia. It is a balance perfectly captured by the text piece, written from Miracleman’s perspective, describing the celebrations commemorating the anniversary of his return. “As it transpired,” Miracleman says, after noting his fears that they would sacrifice animals or children to him, “I was quite touched: they made a bonfire on the wasteland that was once Trafalgar Square and on it heaped their comic books, their films and novels filled with horror, science fiction, fantasy, and as it burned they cheered; cheered as the curling, burning pages fluttered up into the night; cheered to be done with times when wonder was a sad and wretched thing made only out of paper,” a description that is strikingly ironic coming as the opening to a comic book filled with horror, science fiction, fantasy, and wonder. And indeed, the remainder of the brief text piece pushes this irony further, describing Miracleman’s own dreams for the world, including passages like “I dream a world of heroes and exciting clothes, hoods cut away to show the hair or leotards made of flags. I dream insignia, dream lightning flashes, planets, letters, stars; of bob-cut women wearing red stilettos, ice-blue half-length capes; of men in dominos, transparent blouses, slashing elegance of line in every wrinkle, every crease,” a series of wonders that, as Miracleman attests, do not exist in his world, and are thus only made of paper.

|

| Figure 941: Various governments reacting to the disorganization of their nuclear stocks. (Written by Alan Moore, art by John Totleben, from Miracleman #16, 1989) |

Throughout the issue, the wondrous nature of Miracleman’s new utopia is stressed, often with considerable wit, as when the Warpsmith Phon Mooda explains to the UN that “your chemical, biological and nuclear stockpiles are completely disorganized,” and, when asked by a puzzled American diplomat whether she means this on a political level, clarifies that she means that they are disorganized on “a molecular level. We teleported them into the sun fifteen minutes ago,” a joke, of course, recycled from Watchmen and sped up by twenty minutes. (“Later astronomers announced a tiny flare upon the sun’s perimeter,” Miracleman notes subsequently. “In nuclear terms, the sun is an unshielded giant reactor, several million times as big as Earth itself. I don’t suppose it even noticed.”) And Moore visibly relishes in sections such as Miracleman’s extended speech about the folly of money and explanation of the post-scarcity society to come, or his gleefully didactic explanation of how “we legalized all drugs, while saturating the Earth with honest information on their toxic and benign effects.”

|

| Figure 942: Miracleman and Margaret. (Written by Alan Moore, art by John Totleben, from Miracleman #16, 1989) |

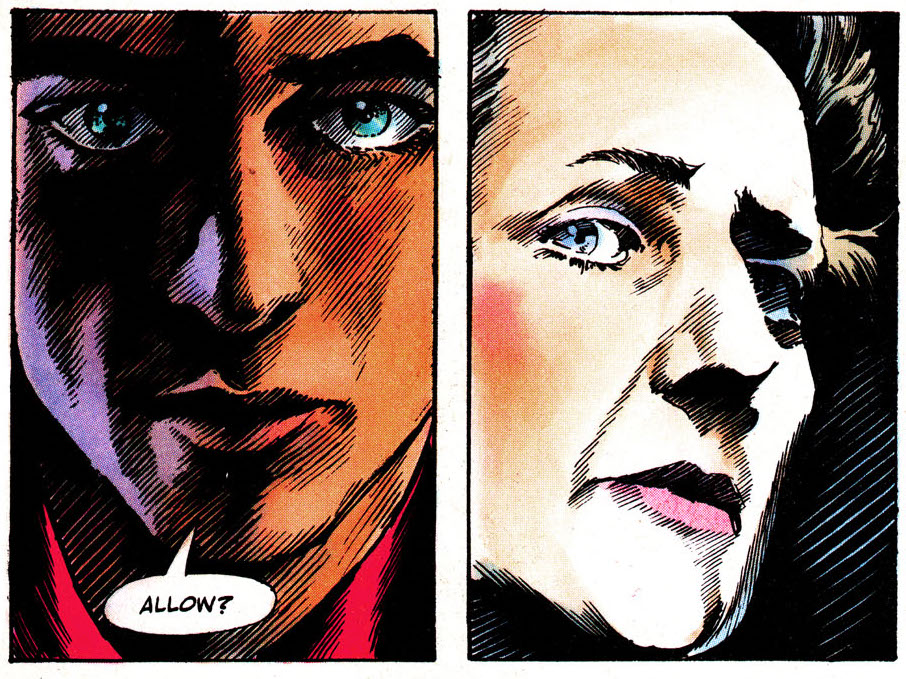

In contrast to this rapture, the sense of unease about utopia can seem muted, not least because Moore devotes more time to skewering the political left (there’s a savage bit of snark about how “when the nuclear power plants, like the bombs before them, found their place within the sun, the unions were at best unsympathetic,” followed by a pretty bruising commentary on radical environmentalists, who “maintained that Africa should starve and die; part of a ‘natural balance,’ while insisting that the smallpox virus had its place in our ecology, and ought to be reproduced,” and who were “mostly Americans” and “well-fed and well inoculated”) than he does offering any significant critique of Miracleman’s program. For the most part, the discontents are portrayed as distinctly unsympathetic types – rural survivalists, religious fundamentalists, and, worst of all, Margaret Thatcher. But this last example also highlights the subtle presentation of this; Thatcher objects to Miracleman’s planned restructuring of the economy, saying, “this is all quite preposterous. We can never allow this kind of interference with the market,” to which Miracleman icily replies, “allow?” The response so utterly crumples Thatcher that Miraclewoman scolds him for being “childish and spiteful,” and as Thatcher leaves, Miracleman reflects on “the way she hung onto the minister beside her, voice too choked to speak, her eyes so dazed. Walking away, she looked so old, so suddenly… I could not hate her.”

|

| Figure 943: Liz Moran critiques Utopia. (Written by Alan Moore, art by John Totleben, from Miracleman #16, 1989) |

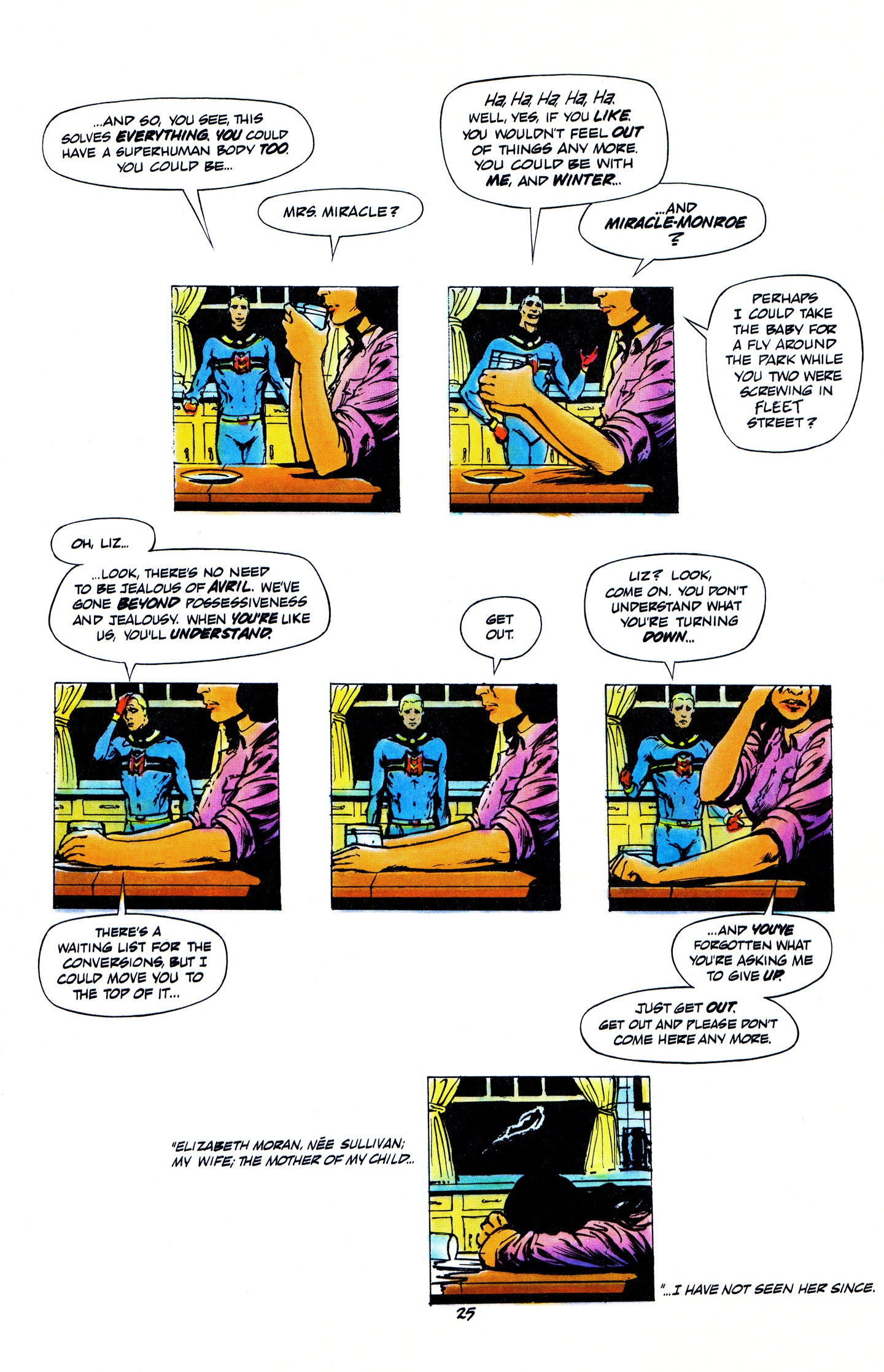

It’s not just that this scene displays a surprising amount of compassion for a woman that Moore, charitably, hated with every fiber of his beard. Rather, it’s that Moore is using the incongruity of presenting Thatcher so sympathetically to make the comic’s presentation of utopia unsettling. For all that it offers no obvious major flaws, and indeed consciously draws the reader’s attention to a number of minor flaws (“Perfection. Not without its problems, I’ll confess; but then without them, could protection be?” muses Miracleman at one point) in order to suggest that these are the extent of utopia’s failings, the comic remains consistently unsettling, for reasons that are difficult to quite articulate. The closest the comic comes is in a one-page scene in which Miracleman visits Liz in order to offer her the chance to be turned into a superhuman, which she angrily rejects, responding to his plea that “you don’t understand what you’re turning down” by claiming that “you’ve forgotten what you’re asking me to give up.” But this is not articulated further, left merely as a poignant and cutting remark instead of as a substantive critique.

This was, of course, the point; as Moore puts it, “what I wanted to do is show just the blissfulness of it all, but at the same time you can’t point your finger on what’s wrong; it’s very difficult. You know there’s got to be something wrong with all this. There’s something that feels wrong.” And for all that Miracleman #16 presents a carefully realized ambivalence on the matter, any suggestion that a committed anarchist like Moore would be on the fence about what he openly admits is “a dictatorship” is ridiculous. As with Watchmen, what Moore is doing is not presenting a vision of the world, but a commentary on the nature of the superhero genre. Much like Miracleman #15 took the idea of the superhero fight to a logical endpoint, Moore’s conclusion to the series looked at the idea of superheroes as figures who saved people and took it to its endpoint, revealing (but not entirely rejecting) the troubling fantasy within.} [Continued… in a couple of weeks]

February 19, 2016 @ 10:38 am

That double-page spread is amazing. Has the artist ever spoken about other influences?, because it reminds me of the warscapes of Dix or Grosz as much as the work of Goya or Brady.

February 20, 2016 @ 4:23 am

Jack, totally agree about the way Totleben’s art recalls German expression. Pictures like Grosz”s The Funeral or The City, or Otto Dix’s Bird’s Hell are what come to mnd, right? Also, the tortured and burning architecture reminds me of the apocalyptic landscapes of Ludwig Meidner. A bit of Itaking futurism in the twisted prespectives and the rather outre ligthing effects (Carlo Carra’s Funeral of the Anarchist Galli).

I’ve loved Totleben’s art here and (working with Steve Bissette) on Moore’s Swamp Thing for decades, as I’ve loved the earlier 20th century artists mentioned here for just as long. But I hadn’t seen the connection until now. Nice one Jack and Phil!

February 20, 2016 @ 9:26 am

Wow yeah, it is an incredible piece of art, certainly a piece that has stuck in my mind (like the other artists you mention Jack) ever since. Definite echoes of Goya and even some of Bosch. And yeah Richard, love your points about German Expressionism – Totleben’s work has for years been a huge influence on my own work, so great to see the remastered spread of London shown here.

Weird thing happened on the comments section here this morning when I opened the webpage – I found not my own name and email details auto-filled, but Sean Dillon’s. Quite odd, especially as I had his email address copied in and I’ve never seen it before.

February 23, 2016 @ 10:38 pm

Not directly relevant to this post, but relevant to the Last War in Albion as a whole, and likely interesting to its readers: an interview with Alan Moore about his theory and magical practice, and some very Alan Moore grumpiness, to boot – http://www.pagandawnmag.org/alan-moore-the-art-of-magic/

February 25, 2016 @ 5:30 pm

Is there some problem with the website? I had a hard time finding this entry. It keeps opening on the previous entry and I had to go to the right hand column to click on this. Today I didn’t see it in the right hand column either and had to go to the February archives to find it.

February 27, 2016 @ 12:55 pm

Well, for one thing this post isn’t tagged so it doesn’t come up when you look for Last War in Albion posts.