Hey, Did You Hear The One About The Nuns? (The Last War in Albion Book Two Part Twenty-Seven: Nemesis)

|

| Figure 938: Miracleman throws a car full of people at Kid Miracleman. (Written by Alan Moore, art by John Totleben, from Miracleman #15, 1988) |

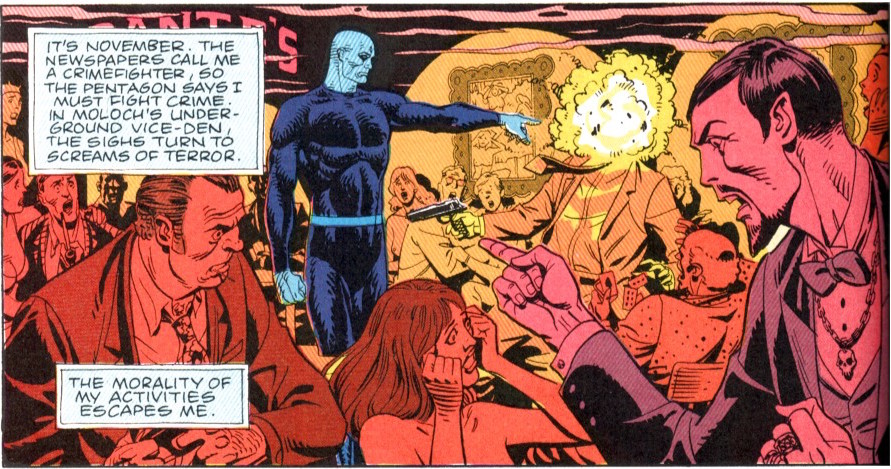

Previously in The Last War in Albion: Coming to the end of his run on Miracleman, Moore decided to grapple with as brutally realistic a portrayal of a superhero fight as he could imagine – to actually show what such a battle would mean for the world in which it took place.

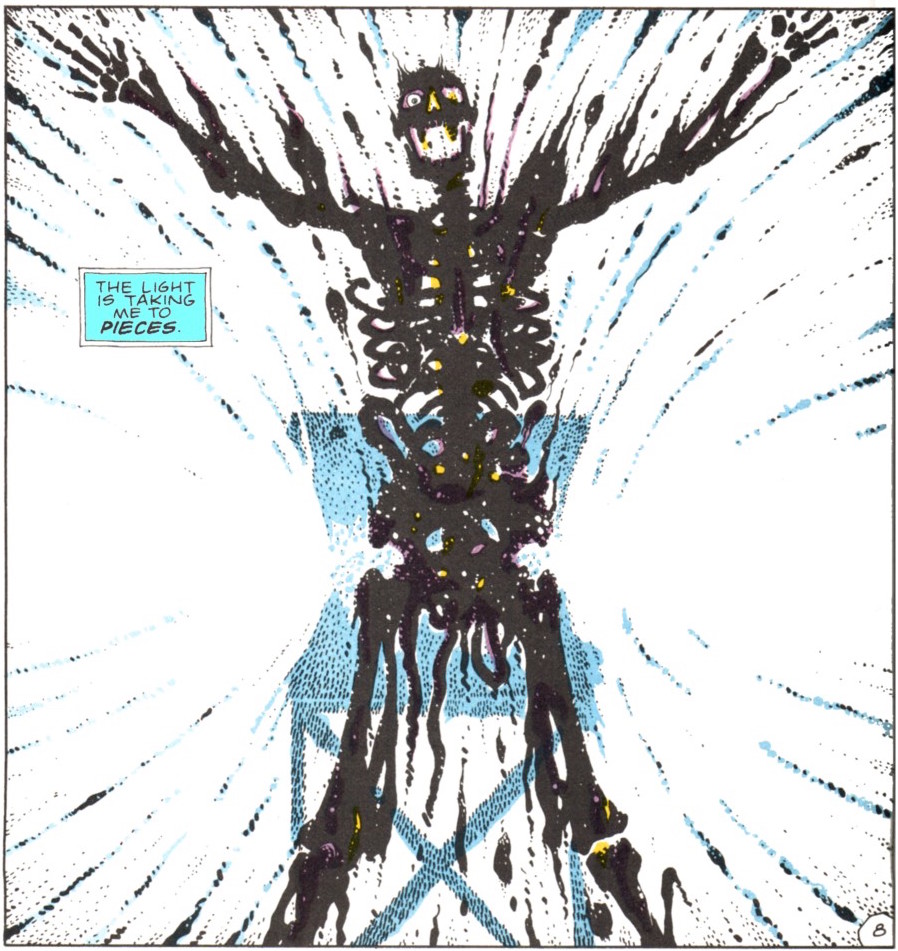

Moore had grappled with some of this in the first Miracleman/Kid Miracleman fight when, for instance, Kid Miracleman hurls a baby through the air in the middle of the fight, distracting Miracleman by throwing a baby at a nearby building, which Miracleman of course saves, but with the note that he’s broken a couple of the baby’s ribs because of the speed he was traveling, a grimly funny note of realism in a standard superhero trope. There’s a not entirely dissimilar moment in Miracleman #15 when Miracleman, in another fairly standard superhero punch-up moment, picks up a car and throws it at Kid Miracleman. “My apologists have claimed the car that I first hurled at Bates was empty, those who’d been inside having all previously escaped,” he narrates. “I’m sorry, but that isn’t true,” the final caption box changing color to be yellow on black – Bates’s colors. The shift in tone – from a winking subversion of the “superheroes save everybody” to a stark-faced refusal to offer any sort of salvation at all – is stunning.

And this is hardly the only such moment in Miracleman #15, an issue that returns over and over again to images of stark brutality. Kid Miracleman, under Moore, had always been portrayed as a brutally sadistic figure, whether in his mocking murder of his secretary in his first appearance “just to show you that I don’t mind doing that sort of thing. In fact, I quite enjoy it” or in his dispatching of the nurse in Miracleman #14. But what is striking – especially for Moore – is that the issue contains almost no textual descriptions of what Kid Miracleman does to London. Early on the narration establishes that Bates spends hours in London before Miracleman and company realize he’s back, and talks about “those hours that he had crammed with centuries of human suffering; those narrow side-streets filled with miles of pain. Having exhausted all the humdrum cruelties known to man quite early in the afternoon he had progressed to innovations unmistakably his own,” and the end narration makes a fleeting and bleak mention of “coral reefs of baby skulls, and worse,” but this is the extent to which Moore uses the written word to frame these depravities into the sort of classic and endlessly quotable lines that had characterized, for instance, Rorschach’s famously bleak narration in Watchmen. There are neither “abattoirs of retarded children” nor “gutters full of blood” to drown the vermin in.

|

| Figure 939: John Totleben’s double page spread of utter carnage. |

{Impressively, Alan Moore’s second publisher for Marvelman/Miracleman was an even bigger trainwreck than his first. It is perhaps unsurprising, given this, to find out that Dez Skinn negotiated the bulk of the deal. The financial plan for Warrior had always involved selling the strips to foreign markets, and Skinn was determined to sell them as a package, reasoning that “strips like Spiral Path – which I put into an anthology alongside Shandor and Bojeffries Saga – were not the stars of the show,” but that Warrior would never have happened without them and that they deserved the same shot at foreign publication as the heavy-hitters like V for Vendetta and Laser Eraser and Pressbutton. But ironically, it wasn’t the lesser Warrior material that made selling the strips abroad a challenge, but the nominal crown jewel, Marvelman, as neither of the two biggest comics publishers would touch it. DC was the obvious first choice, since they were already having considerable success publishing Alan Moore in the US market, and were indeed interested, but Dick Giordano pointed out that there was simply no way that they could publish a comic called Marvelman, citing the number of problems they were already having with Captain Marvel, which they’d bought from the smoldering ruins of Fawcett and started publishing under the name Shazam! But the obvious second choice proved no better; Marvel wouldn’t touch it either, pointing out that if they were to publish a strip called Marvelman it would be read as representing the entire company, which was perhaps not quite what they wanted Moore’s psychologically damaged take on superheroes to do.

{Impressively, Alan Moore’s second publisher for Marvelman/Miracleman was an even bigger trainwreck than his first. It is perhaps unsurprising, given this, to find out that Dez Skinn negotiated the bulk of the deal. The financial plan for Warrior had always involved selling the strips to foreign markets, and Skinn was determined to sell them as a package, reasoning that “strips like Spiral Path – which I put into an anthology alongside Shandor and Bojeffries Saga – were not the stars of the show,” but that Warrior would never have happened without them and that they deserved the same shot at foreign publication as the heavy-hitters like V for Vendetta and Laser Eraser and Pressbutton. But ironically, it wasn’t the lesser Warrior material that made selling the strips abroad a challenge, but the nominal crown jewel, Marvelman, as neither of the two biggest comics publishers would touch it. DC was the obvious first choice, since they were already having considerable success publishing Alan Moore in the US market, and were indeed interested, but Dick Giordano pointed out that there was simply no way that they could publish a comic called Marvelman, citing the number of problems they were already having with Captain Marvel, which they’d bought from the smoldering ruins of Fawcett and started publishing under the name Shazam! But the obvious second choice proved no better; Marvel wouldn’t touch it either, pointing out that if they were to publish a strip called Marvelman it would be read as representing the entire company, which was perhaps not quite what they wanted Moore’s psychologically damaged take on superheroes to do.

It is October 1987. Moore is sitting down to dinner after a Glasgow signing to promote Watchmen. At the table is Grant Morrison, a neophyte comics writer. It is the only meeting between them that Moore recalls, although he had given Morrison advice at a 1983 Glasgow comic mart when Morrison was on the cusp of transitioning from a failed rock star to a successful comics writer. Moore will eventually, to Morrison’s chagrin, describe him as an “aspiring” comics writer at the time of this meeting, one of many swipes he will take at Morrison over the years. They talk about vegetarianism. (“Sometimes you can’t live with the contradictions, Grant,” Morrison recalls him saying.)

It is October 1987. Moore is sitting down to dinner after a Glasgow signing to promote Watchmen. At the table is Grant Morrison, a neophyte comics writer. It is the only meeting between them that Moore recalls, although he had given Morrison advice at a 1983 Glasgow comic mart when Morrison was on the cusp of transitioning from a failed rock star to a successful comics writer. Moore will eventually, to Morrison’s chagrin, describe him as an “aspiring” comics writer at the time of this meeting, one of many swipes he will take at Morrison over the years. They talk about vegetarianism. (“Sometimes you can’t live with the contradictions, Grant,” Morrison recalls him saying.) It’s summer, 1992. Alan Moore is thirty-eight. Just a few years out from the twin smoldering wreckages of Big Numbers and his first marriage, he takes a call from Jim Valentino at Image Comics. Moore is unimpressed with the Image output, thinking, “I’ve been away for five years, and comics have turned into some bizarre super-steroid-mutant hybrid that I’ve got no familiarity with at all,” but the business model of Image appeals to him, and the failure of Big Numbers along with a relatively fallow period in Moore’s output means he needs the money, and so he throws himself into “teaching myself this new language and trying to understand this new audience.” He ends up creating 1963 with Steve Bissette and Rick Veitch, a colorful pastiche of vintage Marvel comics written in explicit contrast to the post-Watchmen style (largely embodied by Image itself) of violent and cynical comics.

It’s summer, 1992. Alan Moore is thirty-eight. Just a few years out from the twin smoldering wreckages of Big Numbers and his first marriage, he takes a call from Jim Valentino at Image Comics. Moore is unimpressed with the Image output, thinking, “I’ve been away for five years, and comics have turned into some bizarre super-steroid-mutant hybrid that I’ve got no familiarity with at all,” but the business model of Image appeals to him, and the failure of Big Numbers along with a relatively fallow period in Moore’s output means he needs the money, and so he throws himself into “teaching myself this new language and trying to understand this new audience.” He ends up creating 1963 with Steve Bissette and Rick Veitch, a colorful pastiche of vintage Marvel comics written in explicit contrast to the post-Watchmen style (largely embodied by Image itself) of violent and cynical comics. It’s January 7

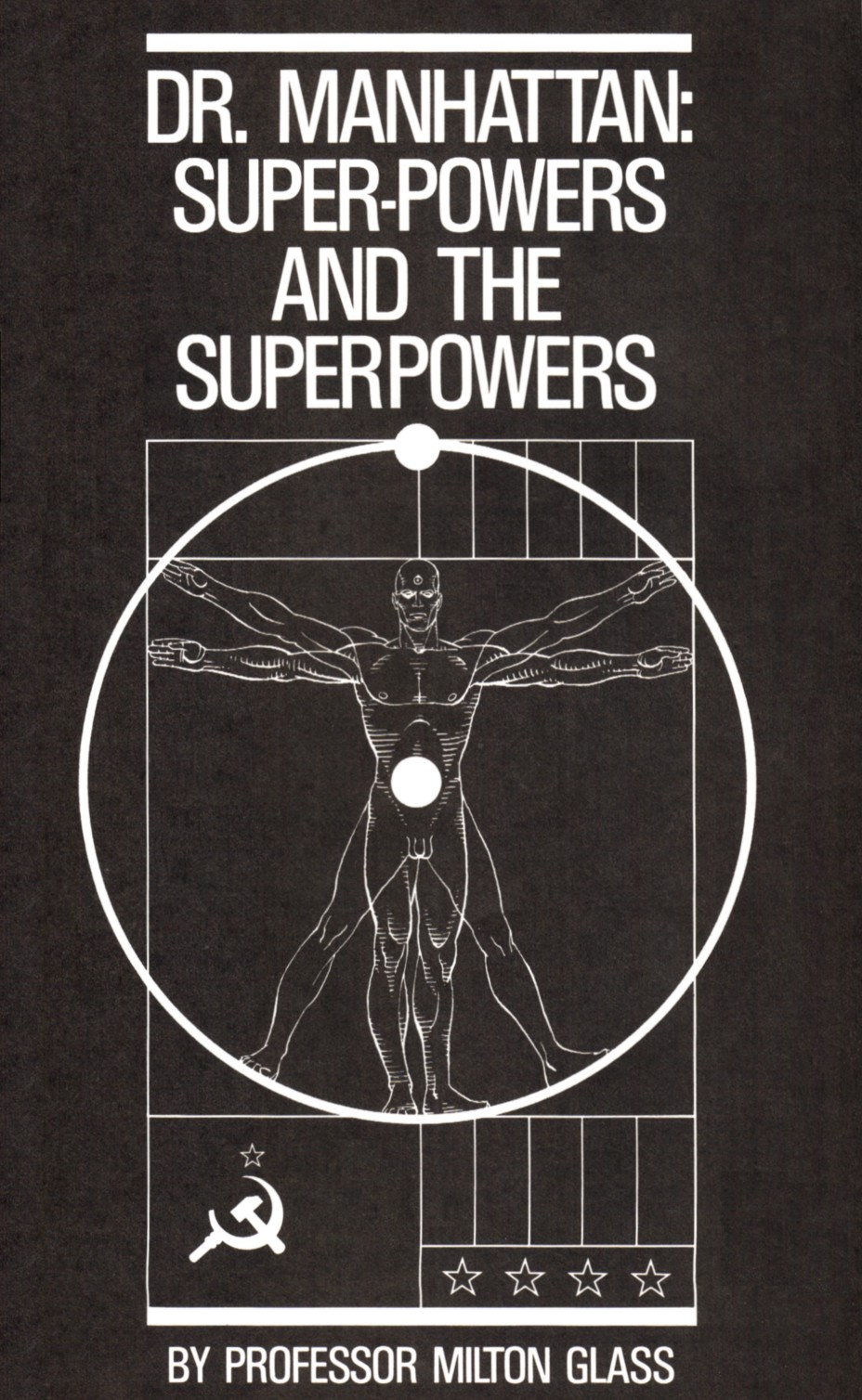

It’s January 7 It is January, 1988. Alan Moore is thirty-three, and writing the introduction to the collected edition of Watchmen. His relationship with the publisher is in tatters, a fact he alludes to only vaguely when he notes that it is “the very last work that I expect to be doing upon Watchmen for the foreseeable future.” He looks back to 1984, when the idea originated, and the giddy enthusiasm of it all. And yet there is something he cannot quite locate in this. He notes that at the start “we wanted to do a novel and unusual super-hero comic that allowed us the opportunity to try out a few new storytelling ideas along the way. What we ended up with was substantially more than that.” But he cannot pin down the transition. Instead he describes a growing realization of the story’s complexity and scale, but without a sense that the realization had an end point. Instead, “there was the mounting suspicion (at least on my part) that we might have bitten off more than we could chew, that we might not be able to resolve all these momentous strands of narrative and meaning that seemed to be springing up wherever we looked, that we might be left at the end of the day with a big, messy, steaming bowl of semiotic spaghetti.” But even when the project ended. But even now, in 1988, Moore is lost in the process, saying that it is only now, in writing the introduction, that he realizes “how dazed a state I’d spent that year in, as if I’d been slam dancing with a bunch of rhinos and the concussion was only just starting to clear up,” a claim that oddly undercuts itself; the daze clearly extending beyond the year, simultaneously located “now, twelve months after” he finished the final script and in the past, as indicated by the past tense in the concussion metaphor.

It is January, 1988. Alan Moore is thirty-three, and writing the introduction to the collected edition of Watchmen. His relationship with the publisher is in tatters, a fact he alludes to only vaguely when he notes that it is “the very last work that I expect to be doing upon Watchmen for the foreseeable future.” He looks back to 1984, when the idea originated, and the giddy enthusiasm of it all. And yet there is something he cannot quite locate in this. He notes that at the start “we wanted to do a novel and unusual super-hero comic that allowed us the opportunity to try out a few new storytelling ideas along the way. What we ended up with was substantially more than that.” But he cannot pin down the transition. Instead he describes a growing realization of the story’s complexity and scale, but without a sense that the realization had an end point. Instead, “there was the mounting suspicion (at least on my part) that we might have bitten off more than we could chew, that we might not be able to resolve all these momentous strands of narrative and meaning that seemed to be springing up wherever we looked, that we might be left at the end of the day with a big, messy, steaming bowl of semiotic spaghetti.” But even when the project ended. But even now, in 1988, Moore is lost in the process, saying that it is only now, in writing the introduction, that he realizes “how dazed a state I’d spent that year in, as if I’d been slam dancing with a bunch of rhinos and the concussion was only just starting to clear up,” a claim that oddly undercuts itself; the daze clearly extending beyond the year, simultaneously located “now, twelve months after” he finished the final script and in the past, as indicated by the past tense in the concussion metaphor. A similar temporal ambivalence exists in the previously discussed description of how his “nostalgia for the [superhero] genre cracked and shattered somewhere along the way and all the sweet old musk inside just leaked out and evaporated,” a statement in which Moore is clearly lying, albeit as much to himself as the reader, the description of the “sweet old musk” evoking precisely what he says he has lost, so that the sentence offers the very experience it exists to reject. Moore casts superheroes away, but in doing so only draws them back in, a tension implicit in the very idea of nostalgia, which is of course an intense feeling for a thing that one is not actually experiencing at the time. He is nostalgic for his nostalgia, relishing in the scent of its memory even as he pushes the genre away, grimly certain in the necessity of all his burnt bridges.…

A similar temporal ambivalence exists in the previously discussed description of how his “nostalgia for the [superhero] genre cracked and shattered somewhere along the way and all the sweet old musk inside just leaked out and evaporated,” a statement in which Moore is clearly lying, albeit as much to himself as the reader, the description of the “sweet old musk” evoking precisely what he says he has lost, so that the sentence offers the very experience it exists to reject. Moore casts superheroes away, but in doing so only draws them back in, a tension implicit in the very idea of nostalgia, which is of course an intense feeling for a thing that one is not actually experiencing at the time. He is nostalgic for his nostalgia, relishing in the scent of its memory even as he pushes the genre away, grimly certain in the necessity of all his burnt bridges.…