Neat Little Analogy, Huh? (The Last War in Albion Book Two Part Twenty-Five: Scenes from The Nativity)

|

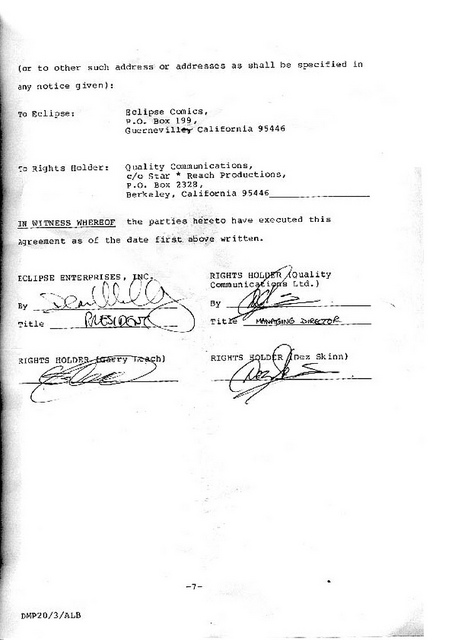

| Figure 923: The signatures upon the contract that led Dez Skinn to go to a seedy bar to pick up a couple thousand dollars in cash. |

This installment of The Last War in Albion contains graphic images of childbirth below the cut.

Previously in The Last War in Albion: In a comedy of errors, Alan Moore’s Marvelman series, originally published in Warrior, was republished under the title Miracleman by Eclipse Comics in the US. But with the reprints running out, Eclipse had to clear the way to commission new material from Moore, which required appeasing Dez Skinn.

Eclipse’s solution, ratified in a new contract dated February 1986 (the same month that Miracleman #6 is dated), was to buy the right to produce new Miracleman material from Skinn for a further $8000, payable in three installments, one of which Skinn recounts was given to him at a meeting “with Jan Mullaney – Dean’s brother – in New York, in some really seedy bar. He turned up looking like a real hippie with a couple thousand dollars in cash in a brown envelope. And I’m sitting there, this sort of funny Englishman in this really scary place and he comes in and this is like some dodgy transaction taking place as he slides the envelope over to me with a couple thousand dollars or more in cash and he says, ‘you will count it, won’t you?’” This contract also seemingly marks the point where Skinn abandoned his support for Alan Davis’s objections to having his work reprinted, noting simply that “Eclipse also assumes the sole responsibility of payment to and for the creative talent on all issues of Miracleman or any such other titles featuring “Miracleman” and the Characters, including payment of artistic royalties to Alan Moore and Gary Leach representing Alan Davis on the stories reprinted from Warrior Magazine,” and transferring all of the design copyrights Skinn had previously asserted that Davis held to Eclipse.

This is perhaps unsurprising – the fact that Skinn had chosen to direct his letter regarding Davis’s objections to Moore suggests that the position was more about trying to force Moore back into playing ball with Dez Skinn than about concern for Alan Davis. Whereas the entire point of this agreement was to clear the way for Eclipse to hire Moore directly (as opposed to the obviously unworkable plan of having Skinn/Quality employ him). For the purposes of filling out Miracleman #6 and publishing #7, Moore’s involvement was minimal – he’d been ahead in scripting for Warrior, and had three installments written but not drawn. But the problem of getting them drawn was more substantial, since it’s not as though Alan Davis was going to be returning to the gig. Unfortunately, Eclipse’s stable of available artists did not come close to matching that of the major companies. They presented Moore with a few options, and of them he picked an neophyte named Chuck Austen, though he was at the time still going by his birth name of Chuck Beckum on the grounds, as Austen put it, that he “didn’t draw everybody so that they looked like they were superheroes in street clothes.”

|

| Figure 924: Chuck Austen’s art failed to live up to the grand melodrama of Moore’s script. (From “First Star I See Tonight,” in Miracleman #7, 1986) |

It’s an accurate enough description, but the truth is that Austen’s blocky art style and relatively static faces are a rough transition from the famous fluidity of Alan Davis’s work, especially coming as they do on a page turn from an exquisite splash page of Miracledog (although actually, Austen handles Miracledog pretty well). And the biggest sequence that Austen drew, Miracleman flying into space with Gargunza, kissing him, and then hurling him at the planet in issue #7, is a desperately unsatisfying one. Austen has talked about how he struggled to give the scene the correct emotional content as requested by Moore in his typically detailed script, saying how “you want Gargunza to look dazed and totally lost and realizing that it’s all over and there ain’t shit that he can do about it. And at the same time you want this almost tender, totally controlling happening in the panel where Miracleman looks like he’s absolutely in control and Gargunza is resigned to the fact. That’s the hardest part to me, and the part that’s also fun. That energizes me, working on that emotional level trying to get the character to express that inner thing that’s going on.” Which is all well and good, although Moore’s captions, which clarify that Gargunza, in the vacuum of space, is “barely conscious” rather cuts against them, but there’s simply no way to avoid the fact that Austen’s static and slightly cartoonish art ends up looking more like Miracleman is throwing a mannequin at the planet. Still, after eighteen months, the cliffhanger was resolved, and audiences at last found out how a depowered Mike Moran escaped the jaws of the mutant canine formerly known as Marveldog.

|

| Figure 925: The Eclipse offices were ravaged by floods in early 1986. (Written by cat yronwode, art by Chuck Austen, from Miracleman #8, 1986) |

At this point, however, things really started to go wrong. Some of this was entirely understandable; in February of 1986 heavy rainfall flooded the Russian River, resulting in a fifty foot flood through Guerneville California, where Eclipse was headquartered. Unsurprisingly, this resulted in delays, with Miracleman #8 being published as a set of Mick Anglo reprints with a Chuck Austen-illustrated framing sequence in which cat yronwode explained the situation while decrying the usual practices of desperate comics publishers where they try to shoehorn reprints into the ongoing narrative. The only direct effect of this was the month delay to Miracleman #9, but it did considerable damage to Eclipse’s finances, exacerbating almost all of the existing issues with the company.

This was also roughly the point where Eclipse lost the services of Chuck Austen after yronwode called Austen at home and screamed down the line at his grandmother because some pages were late, resulting in Austen refusing to work for Eclipse anymore. That meant finding a new artist. But Eclipse very nearly faced an even bigger problem when yronwode attempted the same basic approach with Moore himself, calling him to demand the scripts for forthcoming issues, which Moore had not yet started work on because he was waiting for the issue with Alan Davis’s rights to be settled. As Moore recounts it, “she was being very blustery, and trying to make out that I’d done something wrong, while not answering my questions about this paperwork. She said something else that sounded offensive and I said, ‘Well, perhaps we could just stop the entire project right here,’” resulting in Dean Mullaney, who had apparently been listening in on the call, cutting in to promise that the paperwork was forthcoming, but asking if Moore would start work while waiting for it, which Moore agreed to.

(Moore apparently forgot about the paperwork after this point, or at least did not pursue it further, since, as Davis points out, no such paperwork existed and Eclipse’s reprints of his material were entirely unauthorized. Davis, for his part, is absolutely withering about this anecdote, noting that he “felt really sad that Alan’s work had been so badly impaired by deep concern over the legality of Eclipse publishing MY art. He was so distraught in fact, that he must have forgotten he had my address and telephone number, or if he was too nervous to call, could have contacted me via a mutual acquaintance like Jaime Delano.”)

|

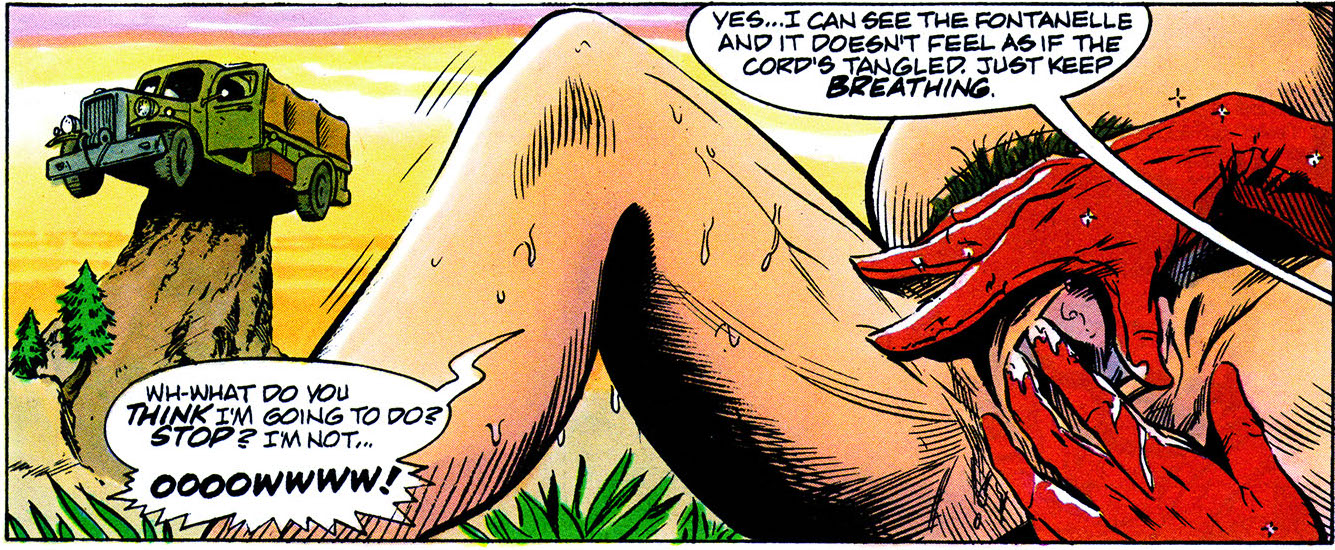

| Figure 926: “Scenes From The Nativity featured graphic depictions fo childbirth. (Written by Alan Moore, art by Rick Veitch and Rick Bryant, from Miracleman #9, 1986) |

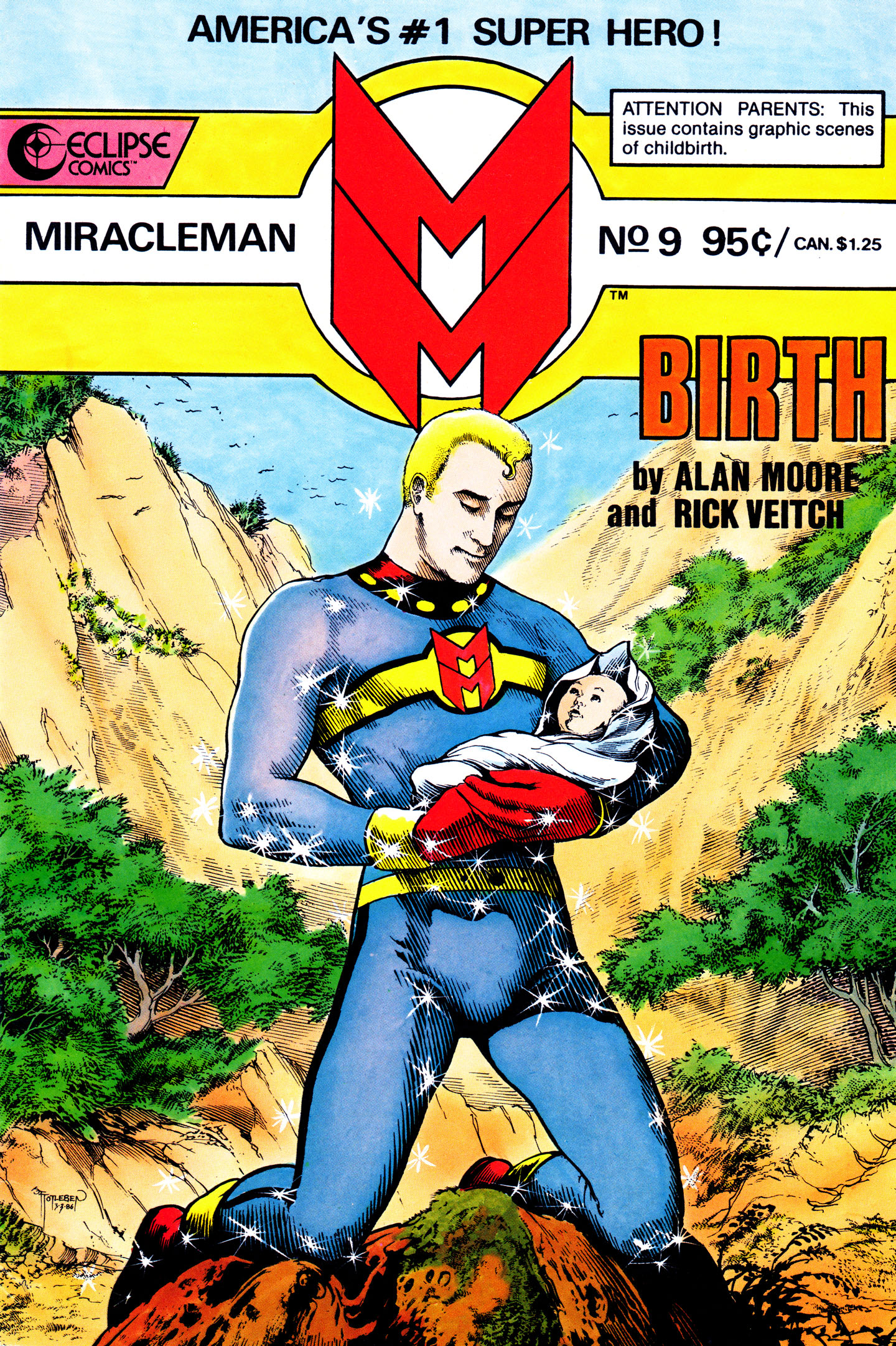

With Moore mollified, work could begin on what would end up being one of the most famous issues of Miracleman, and indeed of Moore’s career – one that would, indirectly, lead to the fracturing of his relationship with his other major American publisher, DC Comics: “Scenes From the Nativity.” On art chores for it was Moore’s frequent Swamp Thing collaborator Rick Veitch (explaining, perhaps, why John Totleben stepped in to do the conclusion of the “Greening of Gotham” arc at around the same time). And what a job Moore gave him; the issue featured, as the warning label on the cover put it, “graphic scenes of childbirth,” which is to say five detailed panels over the course of the issue of Liz and Miracleman’s child emerging from the birth canal. The story had been one Moore had been planning for some time; Moore recalls a conversation with Dez Skinn in the latter days of Warrior where he noted that, with Liz pregnant, they were going to have to tackle the birth of her child at some point. “I suppose it depends what kind of angle you take upon it,” Skinn replied, to which Moore said, “well, how about from the front?”

|

| Figure 927: John Totleben’s cover to Miracleman #9, featuring an explicit content warning made to look like a Surgeon General’s warning. |

This is difficult to quite believe, at least as a sincere suggestion to Skinn who, by that point, had already had a small freakout over Moore’s use of the word “period” in an earlier installment, although given how fraught Moore and Skinn’s relationship was by the end of the comic’s Warrior run it’s certainly possible that Moore was simply seeking to wind him up as opposed to making a proposal he actually thought was likely to make it into the comic. But either way, now that he was free of Skinn and clearly at a publisher that needed him more than he needed them he decided to go with it. This was, by all appearances, the plan from the start of the Eclipse iteration of the story – Austen recalls talking to yronwode about the forthcoming issue, saying that she “was not really happy about the idea. ‘You’re taking a super-hero book and you’re putting a birth scene in the middle of it.’” yronwode, for her part, vigorously disagrees with this account, noting that Eclipse had previously published Sabre, which had a depiction of childbirth “although after the art was drawn, a word balloon was put over the woman’s vagina and it was covered up,” and that an earlier issue “was, as far as I know, the first American four-color comic that showed a girl getting her first menstrual period.” In her telling, she firmly “didn’t think there was going to be any problem,” and indeed claimed to have obtained the photo reference used by Veitch by photocopying pages of Lennart Nilsson’s A Child is Born, saying that “if you compare the book – which is available in almost every public library – with the pictures in Miracleman you’ll see that they are copies from that,” presumably assuming nobody would bother to do so, as it’s not even remotely true.

For Moore’s part, the point was straightforward. “I’ve seen some birth scenes in comics where it seems that the artist has probably taken the woman’s poses from a porn magazine. Just change the expression on the faces slightly and everything was posed so that you can’t actually see the genital area. And it struck me, having seen a couple of childbirths m’self – I mean, I find them quite magnificent. Stunning. Both occasions were stunning occasions; it was an incredible kinda powerful moment. I thought, well, this was something sacred I’m talking about. I really shouldn’t have to be bothered with the self-imposed problems and laws or whatever of the American comics industry.” And indeed, the issue fits smoothly into the larger pattern of Moore challenging the censorship of the American comics industry, first with getting DC to publish Swamp Thing without the approval of the Comics Code, then subsequently in his decision to do issues about menstruation and psychedelic vegetable sex. And, of course, it was Miracleman #9 that provoked Steve Geppi into launching a moral crusade to clean up comics, resulting in DC’s proposed ratings system and Moore’s schism with the company.

|

| Figure 928: Miracleman reflects on Mike Moran’s life and past as the birth of his daughter approaches. (Written by Alan Moore, art by Rick Veitch and Rick Bryant, from Miracleman #9, 1986) |

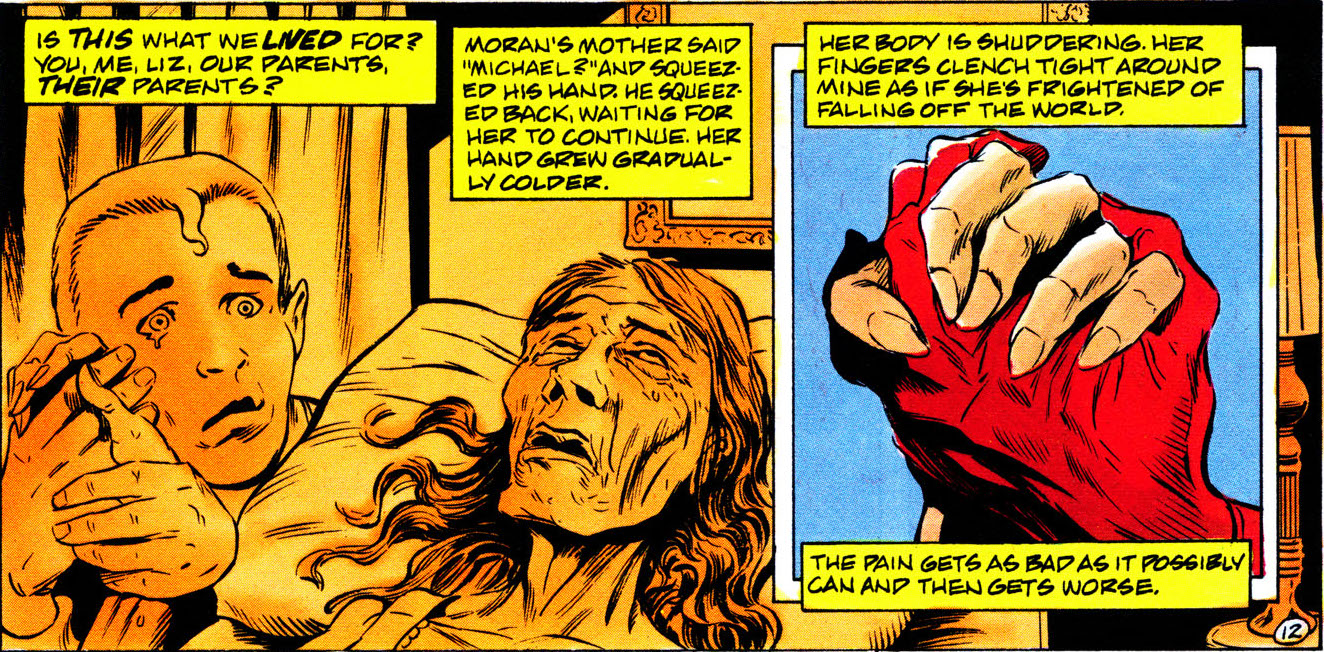

While the five panels explicitly depicting Liz Moran’s vagina caused the lion’s share of reaction to Miracleman #9, they were far from the whole of the issue. Miracleman #9 marks the first time Moore wrote an installment of Miracleman as a single issue, although notably he still structures it as two short scenes (an eight-pager and a six-pager) separated by a two page interlude focusing on Johnny Bates. The first section deals fairly straightforwardly with Miracleman and Liz’s reunion and exit from the Zarathustra complex, depicting it straightforwardly and without captions. The second section, on the other hand – the one actually depicting the birth – runs alongside narration from Miracleman addressed at the late Emil Gargunza, with full color panels of Liz giving birth juxtaposed with sepia-toned flashbacks of major events in the character’s mythos. So, for instance, as Miracleman asks “is this what we lived for? You, me, Liz, our parents, their parents? Moran’s mother said ‘Michael?’ and squeezed his hand. He squeezed back, waiting for her to continue. Her hand grew gradually colder. Her body is shuddering. Her fingers clench tight around mine as if she’s frightened of falling off the world. The pain gets as bad as it possibly can and then gets worse,” the art first features a young Michael Moran crying by his mother’s deathbed, and then, with the switch to “her body is shuddering,” a close-up of Liz and Miracleman’s hands entwined.

|

| Figure 929: The sepia-toned flashbacks recede as the sacred moment arrives. (Written by Alan Moore, art by Rick Veitch and Rick Bryant, from Miracleman #9, 1986) |

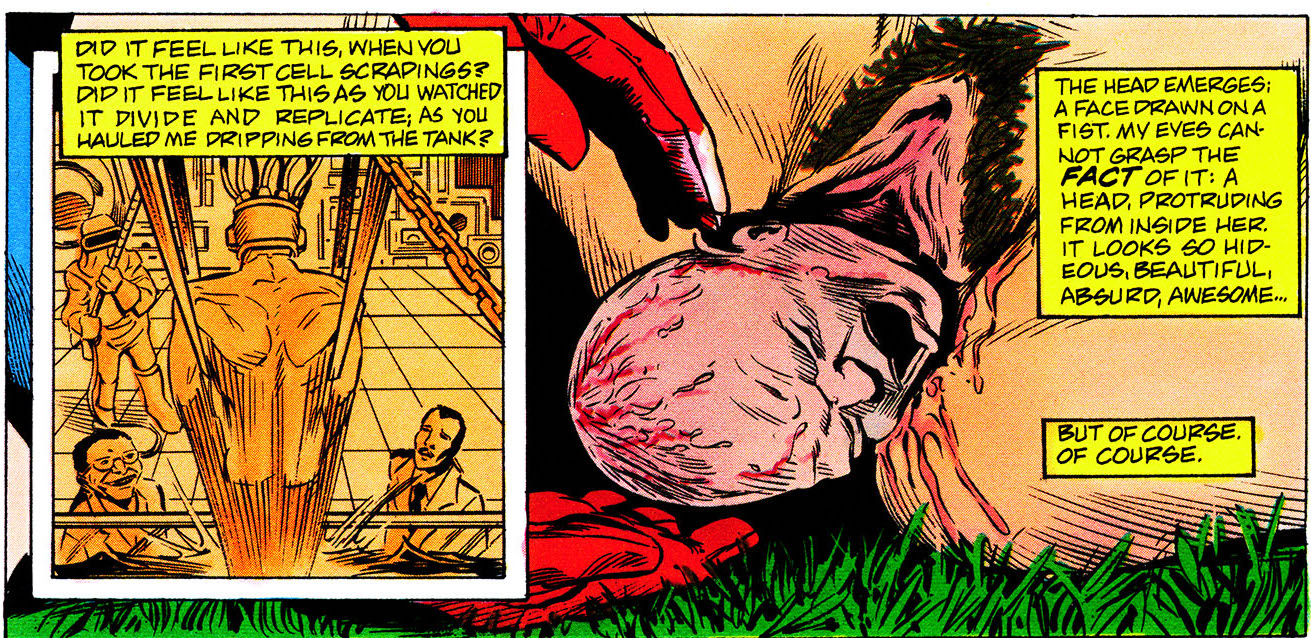

As the sequence reaches its most famous page, it switches structure, the sepia-toned panels becoming insets on the full-color ones instead of the other way around as the baby’s head emerges. “Did it feel like this, when you took the first cell scrapings,” Miracleman asks the absent Gargunza. “Did it feel like this as you watched it divide and replicate; as you hauled me dripping from the tank? The head emerges; a face drawn on a fist. My eyes cannot grasp the fact of it: a head protruding from inside her. It looks so hideous, beautiful, absurd, awesome. But of course. Of course.” And finally, as Miracleman grasps his daughter’s head to finish delivering her, he asks, “was it worth it? Worth the risk of loosing gods and monsters on the world? Worth all the blood and violence? [continued]

February 6, 2016 @ 12:11 pm

I really like Alan Moore, but his treatment of Alan Davis regarding this is pretty shabby.

BTW when is the parenthesis you opened last week’s installment going to close?

February 6, 2016 @ 6:40 pm

You’re talking about the {, right? I use those to bracket the chapter-ending essays corresponding to the text pieces. This one runs for two more parts, making Chapter Four a six-parter in total. (Chapters 1-3 had all been seven-parters.)

And yeah, I agree, that’s decidedly not Moore’s finest hour.

February 7, 2016 @ 7:57 pm

It always bugged me that you could pretty much show as much graphic violence as you liked in (non-Comics Code) comics, but showing birth caused a huge ruckus. What does that say about our society?

February 9, 2016 @ 11:17 am

Yeah certainly agree not Moore’s best moment at all. Still love the work produced though, but what a mess all of it!

Totally with you John above that it is such a huge shame that people can freak over the beautiful act that brings us into the world, but glorify violence, especially violence towards women in the media. As you say, this says a lot about us.

February 9, 2016 @ 11:18 am

And I love that you posted images from the comic Phil – thanks.