His Name Burning, His Voice Below Things. All Suffering Nourishes That Presence (The Last War in Albion Book Two Part Thirty-Three: Tyger)

Previously in The Last War in Albion: Blake’s artistic career was a continual and unceasing war against the very notion of certainty and fixity, as represented in the figure of Urizen.

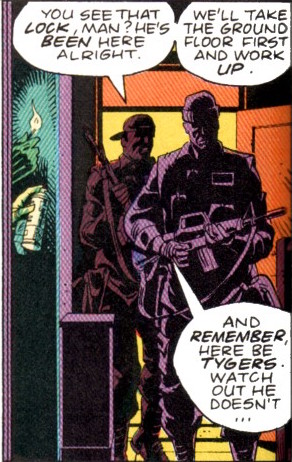

But there is a more foundational aspect of Blake’s unfixed style – one upon which these textual incommensurabilities build. Blake’s illuminated works exist in individually printed and hand-colored copies, no two of which are identical. In the case of The Book of Urizen, for instance, eight copies are known to exist, six of which are widely available. And the differences among these copies are significant; as mentioned, the fourth plate (from which the “solid without fluctuation” line originates) only exists in three of the copies. No two copies place the full-plate illustrations in the same order or locations throughout the text. Plates 8 and 10 each contain the beginning of a section labeled Chapter IV, each of which begins with a stanza numbered 1; on top of that, the order of the two plates is reversed in several copies. Several illustrations change dramatically across copies as well; Plate 6 depicts three figures hung upside-down, bound in serpents, and cast into fire, save for in Copy D, where there is but a single figure. Plate 16, meanwhile, depicts Los in two of the three copies in which it is included, while in a third the figure is given a white beard indicating that it is Urizen. And these are just the variations with the biggest interpretive implications: every page of every copy has its own idiosyncratic decisions of coloring. Nor is this phenomenon unique to The Book of Urizen. Even Blake’s most iconic and nominally fixed poem, “The Tyger,” exists in nearly thirty separate copies, printed and colored over the course of more than thirty years, with major differences across the coloring.

But there is a more foundational aspect of Blake’s unfixed style – one upon which these textual incommensurabilities build. Blake’s illuminated works exist in individually printed and hand-colored copies, no two of which are identical. In the case of The Book of Urizen, for instance, eight copies are known to exist, six of which are widely available. And the differences among these copies are significant; as mentioned, the fourth plate (from which the “solid without fluctuation” line originates) only exists in three of the copies. No two copies place the full-plate illustrations in the same order or locations throughout the text. Plates 8 and 10 each contain the beginning of a section labeled Chapter IV, each of which begins with a stanza numbered 1; on top of that, the order of the two plates is reversed in several copies. Several illustrations change dramatically across copies as well; Plate 6 depicts three figures hung upside-down, bound in serpents, and cast into fire, save for in Copy D, where there is but a single figure. Plate 16, meanwhile, depicts Los in two of the three copies in which it is included, while in a third the figure is given a white beard indicating that it is Urizen. And these are just the variations with the biggest interpretive implications: every page of every copy has its own idiosyncratic decisions of coloring. Nor is this phenomenon unique to The Book of Urizen. Even Blake’s most iconic and nominally fixed poem, “The Tyger,” exists in nearly thirty separate copies, printed and colored over the course of more than thirty years, with major differences across the coloring.

|

| Figure 962: One of the few versions of “The Tyger” in which the beast actually seems to burn bright in a forest of the night. (By William Blake, from Songs of Innocence and Experience Copy T, written 1794, printed 1818) |

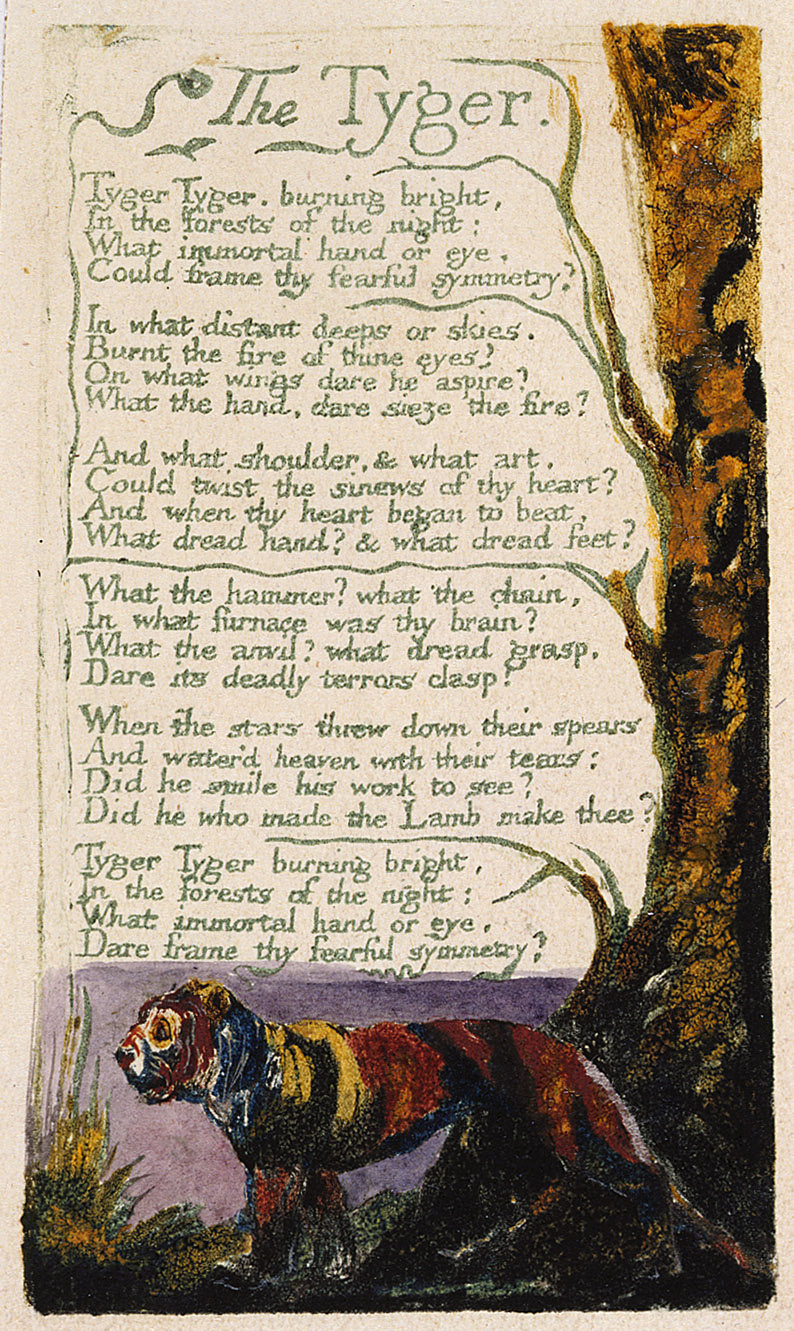

“The Tyger” is a fitting thing to look at here, not least because it shares some of the particular horror of The Book of Urizen with its deadly terrors, dread grasp, and, perhaps most obviously, its fearful symmetry, a phrase that seems tailor made for the geometric precision of Urizen. But more than that, “The Tyger” illustrates another means by which Blake destabilizes his texts, namely the gap that opens up between image and text. For all the anthology-friendly bombast of the poem, after all, it is impossible to escape the fact that in the overwhelming majority of the copies, the image is not that of a monstrously incandescent Tyger, but of an ordinary, at times even downright goofy looking tiger. This is not universally true – in particular, Copies T and F adopt a strikingly dark color palate, such that the flashes of yellow and orange really do seem to burn brightly out of some limitlessly dark woods. But for the most part Blake uses the image to undercut the poem, re-emphasizing the children’s primer Innocence of the book’s dualism instead of allowing Experience to define the tone of the page. Variations on this are a common technique in Blake, whose images often bear an oblique and difficult to surmise relation to the text, not so much illustrating as complicating it.

And yet for all of this, it is the frenzied, obsessive energy of the works that shines through. It’s not just the desperate, constant desire for escape – the way in which Blake seems to be flinging himself at the doors of perception, seeking not merely to cleanse them but to knock them off their hinges entirely. It is the way in which to read them is to be drawn into the act – to be forced to join Blake in his ceaseless, furious quest to see more and deeper. One does not keep up with Blake in doing so; he is always just ahead, always on to something else by the time you’ve caught up to what he was doing. It is easy to be left in a state of dazed exhaustion when reading Blake; The process is frustrating, and moreover eternally frustrated, whether by fundamental unknowability of his vision, the limitations of the existent texts, or simply by the inevitable inadequacies of the reader. But this does not matter; one does not read Blake because the task will succeed. One reads his work for the same reason that he created it: because we have to. Because we are compelled.

And yet for all of this, it is the frenzied, obsessive energy of the works that shines through. It’s not just the desperate, constant desire for escape – the way in which Blake seems to be flinging himself at the doors of perception, seeking not merely to cleanse them but to knock them off their hinges entirely. It is the way in which to read them is to be drawn into the act – to be forced to join Blake in his ceaseless, furious quest to see more and deeper. One does not keep up with Blake in doing so; he is always just ahead, always on to something else by the time you’ve caught up to what he was doing. It is easy to be left in a state of dazed exhaustion when reading Blake; The process is frustrating, and moreover eternally frustrated, whether by fundamental unknowability of his vision, the limitations of the existent texts, or simply by the inevitable inadequacies of the reader. But this does not matter; one does not read Blake because the task will succeed. One reads his work for the same reason that he created it: because we have to. Because we are compelled.

“Symmetry becomes it. Come to ruin our impending feast, a presence that nourishes suffering. All things below voice his burning name. His turmoil offers only truth, in which longer moments live. Let consciousness recapture the flicker it saw then. Torch our continuity of thought now until that mind evaporates. Lust after shadows in us, rend that lace of promises broken and white lies. Regard our love of wreckage, the way our heads thunder approaching that warning pulse and temple of throbbing light that is Asmodeus.” – Alan Moore, “The Demon Regent Asmodeus”

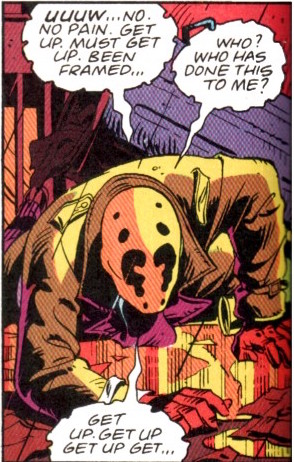

{By most standards, “In Pictopia” is best approached as one of the footnoted curios of Alan Moore’s career, of a type with “Not! The World Cup,” “Captain Airstrip One,” or his 1984 short story “Sawdust Memories,” with which it shares at least some affinity. It’s a mere thirteen page story, scripted by Moore as eight but expanded by primary artist Don Simpson, and has been collected only sporadically, reprinted only in a 1990 best-of-decade collection from Fantagraphics and the first edition of The Extraordinary Works of Alan Moore, both out of print. Several online editions exist, at least one with Moore’s blessing, but it remains, by any reasonable standard, one of Moore’s many obscurities. And yet despite unquestionably being obscure, it is a work with a surprisingly robust reputation. A 1999 best-of-century list in The Comics Journal, for instance, put it at 92nd place, immediately behind Watchmen. (The other War-relevant placings are Mr. Punch at 90th, V for Vendetta at 83rd, and From Hell at 41st; the top three were Pogo, Peanuts, and Krazy Kat.) It was one of many strange decisions in the list, to be sure, but it speaks volumes about the regard in which “In Pictopia” is held by its admirers.

{By most standards, “In Pictopia” is best approached as one of the footnoted curios of Alan Moore’s career, of a type with “Not! The World Cup,” “Captain Airstrip One,” or his 1984 short story “Sawdust Memories,” with which it shares at least some affinity. It’s a mere thirteen page story, scripted by Moore as eight but expanded by primary artist Don Simpson, and has been collected only sporadically, reprinted only in a 1990 best-of-decade collection from Fantagraphics and the first edition of The Extraordinary Works of Alan Moore, both out of print. Several online editions exist, at least one with Moore’s blessing, but it remains, by any reasonable standard, one of Moore’s many obscurities. And yet despite unquestionably being obscure, it is a work with a surprisingly robust reputation. A 1999 best-of-century list in The Comics Journal, for instance, put it at 92nd place, immediately behind Watchmen. (The other War-relevant placings are Mr. Punch at 90th, V for Vendetta at 83rd, and From Hell at 41st; the top three were Pogo, Peanuts, and Krazy Kat.) It was one of many strange decisions in the list, to be sure, but it speaks volumes about the regard in which “In Pictopia” is held by its admirers.

_(d)(w)_(hiddenleaf)__0042.jpg) |

| Figure 963: “In Pictopia”‘s improbable entry on The Comics Journal‘s best-of-century list. |

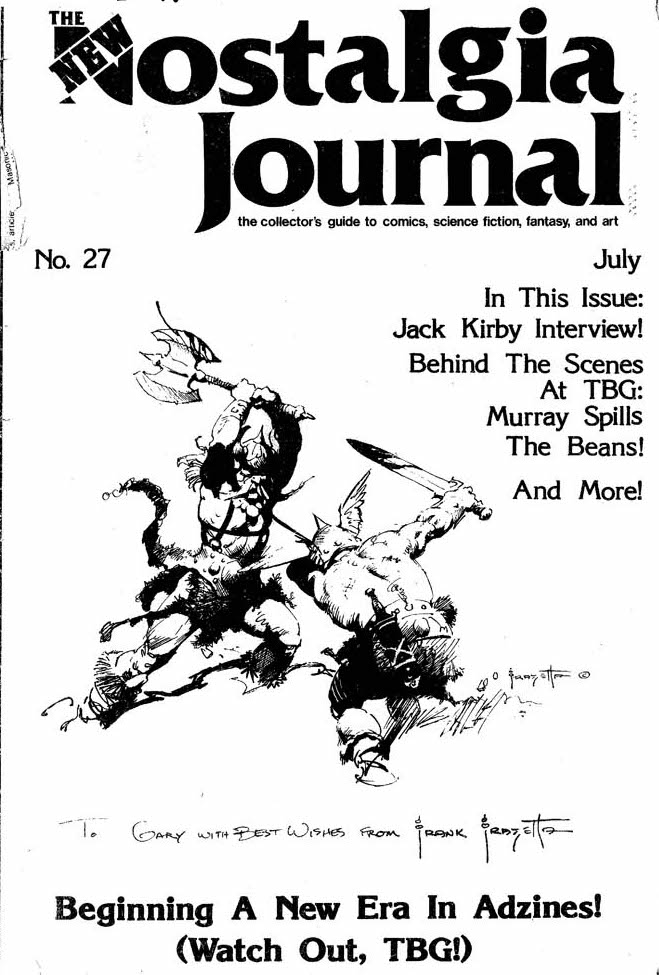

That The Comics Journal should produce such an idiosyncratic list is not surprising, the inclusion of “In Pictopia” ultimately included. From its 1976 start the magazine, and more broadly its publisher, Fantagraphics Books, has occupied an odd place in American comics culture. Both magazine and company started when Gary Groth and Michael Catron, two DC-area comics fans in the outermost orbits of the industry (Catron was the assistant to DC editor Mike Gold, while Groth had run a few conventions and been offered but declined a low-level editorial position at Marvel) bought out an ad-supported fanzine called The Nostalgia Journal, quickly renaming it The Comics Journal after a few issues.

|

| Figure 964: The first Groth-edited issue of The Comics Journal, still under its previous title. |

Groth, who took the reins on The Comics Journal, proved an adept editor. Notably, he started as he meant to go on, using his first editorial, in The Nostalgia Journal #27, cover-dated July of 1976, to lay into Alan Light, who had been the publisher of Groth’s previous publication, the Fantastic Fanzine, and who continued to publish The Buyer’s Guide for Comics Fandom, which Groth openly admitted was the primary competition for The Nostalgia Journal, to the point of proclaiming “Watch out, TBG” on the cover of the issue. Inside the pages, Groth’s attack was sweeping, referring to Light as “the dark side of fandom” and saying that “over these last six years [Light] has told me as much about the American character as Nixon and the whole Watergate dungheep ever could.” But the touch of outright genius was that this attack, which took up five full pages of Groth’s thirty-five page first issue, was accompanied by a page-and-a-half interview with Alan Light and Murray Bishoff, which Groth has the breathtaking cheek to blithely describe in his editorial with a simple “we will try to present a fan or pro interview every issue; this issue we present a sportive conversation with Alan Light and Murray Bishoff and a short, but interesting interview with the comics’ consummate storyteller, Jack Kirby.” Notably, this takes place the paragraph before Groth launches into his five pages of invective against Light.

|

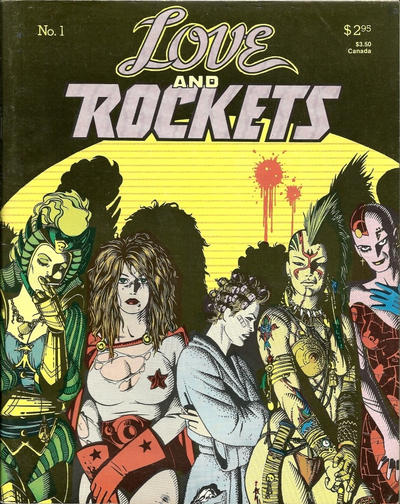

| Figure 965: The first Fantagraphics issue of Love and Rockets, with a cover by Jamie Hernandez. (1982) |

For all Groth’s propensity for a scrap, however, The Comics Journal took a relatively highbrow perspective on the industry. It covered the goings-on of Marvel and DC, but with a practiced disdain, as evidenced by their 1986-87 coverage of DC’s ratings system controversy, which was on the one hand by far the most in-depth going on, to the point where the incident can fairly be described as having played out in the pages of The Comics Journal, and on the other inclined towards a “plague on all their houses” perspective that viewed everyone involved as being childish and overdramatic. In contrast to American superheroes, they championed a literary tradition of comics that incorporated not just the heritage of American newspaper strips implied by their 1999 best-of list but things like the Underground Comix tradition of R. Crumb. This represented something of a synergy-minded editorial position, as Fantagraphics at large quickly established itself as the vanguard of the emerging alternative comics scene, most obviously by becoming the publisher of Gilbert and Jamie Hernandez’s Love and Rockets (from which David J Haskins’s post-Bauhaus band would draw its name).

The result was a strange hybrid of a magazine, simultaneously serving as a tastemaker for self-professedly erudite fans interested in the artistic capabilities of the medium and as an acerbic chronicler both loved and hated by mainstream superhero fandom. And both of these tendencies were on full display in The Comics Journal #53, their 1980 Winter Special, which featured an interview with Harlan Ellison, one of the most acclaimed writers of the American wing of the 1960s New Wave of Science Fiction, and a favorite of those inclined to argue for the genre’s literary respectability. Ellison’s propensity for outspoken bluntness exceeds that even of Alan Moore, and he is in rare form in the interview, already holding court about his opinions on comics by the time Groth’s got the tape recorder running so that the interview begins in mid-thought, with Ellison grousing that DC legend Dennis O’Neil “has got the fatal flaw that I think is shared by many of these fellows.” It continues in much the same vein, with Ellison sneering at comics figures both major and minor with varying degrees of affection (O’Neill is actually, along with Len Wein, one of Ellisson’s two favorite comics writers) for thirty-one pages.

|

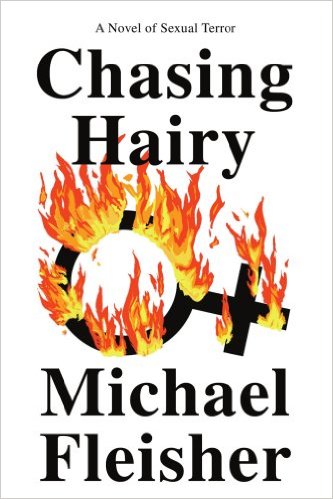

| Figure 966: “Hairy,” in this context, is vulgar slang for female genitalia. |

This would be par for the course for both Ellison and The Comics Journal were it not for a Ellison’s discourse upon the work of Mike Fleisher, who he proclaims to be “crazy as a bed bug,” a “derange-o,” and “certifiable,” a remark Ellison notes “is a libelous thing to say.” In fact this last claim would be tested when Fleisher sued Ellison and Groth for libel, asking for two million dollars in damages. Admittedly, it’s not hard to see why Fleisher was aggrieved, not least because Ellison wrongly asserts that Publisher’s Weekly had proclaimed Fleisher’s novel Chasing Hairy to be “the product of a sick mind.” Equally, Ellison is entirely fair to describe the novel as “about a couple of guys who like to beat up women and make them go down on them. In the end they pick up some woman – a hippie or whatever the fuck she is – and set fire to her and she loves it so much she gives them a blow job.” So while Ellison certainly misquotes Publisher’s Weekly, he’s not exactly wrong in characterizing the book.

The resultant lawsuit hung over The Comics Journal for several years, fracturing the relationship between Groth and Ellison in the process. The eventual trial, at the end of 1986, was a vicious affair on all sides. Fleisher’s lawyers described The Comics Journal as an “elitist, muckracking” publication, not entirely unreasonably, while Ellison took pains to point out the number of times he applied the epithet “bugfuck” to himself and people he admired (indeed, Ellison’s transition into Fleisher was applying the “crazy as a bed bug” descriptor to Steve Gerber’s legendary Howard the Duck run) and Groth’s lawyer observed that Fleisher’s income had actually increased since the Ellison interview, undermining Fleisher’s claim of damages, while further testimony was provided by Jim Shooter and Dean Mullaney. By the end matters descended into farce, with arguments over whether Ellison was, as his attorney tried to present him, a respected literary writer and significant figure in the American Civil Rights movement or, as Fleisher’s attorney presented it, just another hack turning out scripts for publications like Heavy Metal and Creepy, a debate that in many ways embodied the editorial contradictions at the heart of The Comics Journal itself.

|

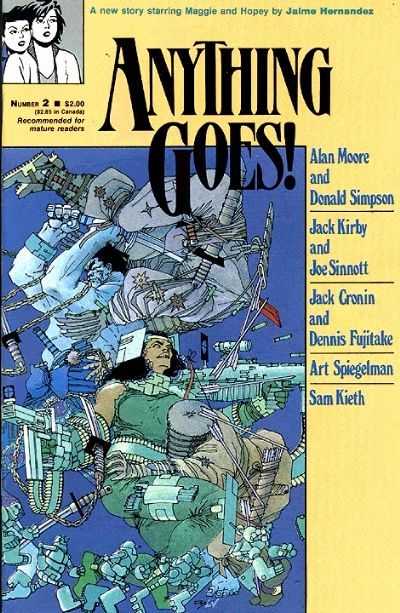

| Figure 967: The Frank Miller-drawn cover of Anything Goes #2, which included “In Pictopia” |

In the end Groth and Ellison prevailed, but the suit was an expensive nightmare for all parties, and in order to pay its legal bills Fantagraphics published a six-issue anthology entitled Anything Goes featuring a marquee collection of contributors including Jack Kirby, Gil Kane, Stan Sakai, Frank Miller, Marv Wolfman, Neal Adams, Dave Sim, Art Spiegelman, the Hernandez Brothers, George Pérez, Kevin Eastman, R Crumb, and Eddie Campbell, along with Moore and Simpson’s “In Pictopia.” That Moore should be drawn to the cause is hardly surprising – it was after all exactly the sort of freedom of speech issue that reliably animated Moore, and he was hardly a fan of Fleisher, who he presented in 1983, perhaps with the pending libel suit against The Comics Journal in mind, as an example of a comics writer who was “dishing up evil, sordid little adult fantasies as suitable for the growing minds of healthy boys and girls” due to an issue of Brave and the Bold featuring Black Canary stripped to her underwear and in bondage while the villain leered over her.

On top of that, the editorial position of The Comics Journal was one that suited Moore. His affection for superheroes was, perhaps, more genuine and less opportunistic than The Comics Journal, which often seemed to cover them out of grudging obligation to the bottom line. But nevertheless the sort of audience The Comics Journal catered to – people interested in superheroes but also in a value judgment that treated them as lower quality, less literary efforts – were exactly the sort of people Moore’s work was most likely to appeal to, whether it was in the “smart superheroes” vein of things like Watchmen and Miracleman or the decidedly-not-superheroes vein of The Bojeffries Saga, which he and Parkhouse penned an installment of (“Batfishing in Suburbia”) in the April 1986 issue of Fantagraphics’ Dalgoda. And The Comics Journal had been an early booster of Moore’s American work, proclaiming issue #93 the “Swamp Thing issue, and anchoring it with a fifty page run of interviews with Bissette, Totleben, and Moore. Indeed, this was Moore’s first major US interview, the issue being dated September 1984, just a year after Moore started on Swamp Thing. (He makes reference at the end to preparing a pitch for Challengers of the Unknown, which would have had him working with Dave Gibbons and looking at how Superman’s arrival affected the Cold War, a detail notable mostly because it means that Watchmen wasn’t even in progress yet when he did the interview.)

|

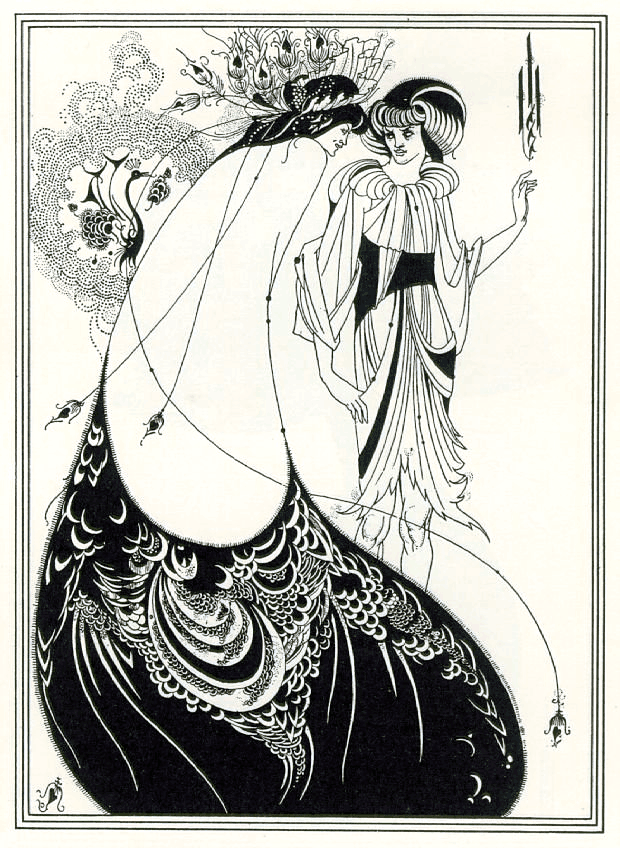

| Figure 968: The Peacock Skirt, by Aubrey Beardsley (1893) |

Indeed, if anything what’s surprising is how little Moore actually worked with Fantagraphics, given that he visited Gary Groth on his first American visit, the same month that The Comics Journal #93 was published. Some of this is due to happenstance – one of his many failed attempts to get a book called Dodgem Logic off the ground, for instance, was to be an anthology series published by Fantagraphics that he described at the 1985 San Diego Comic-Con as starting with a black comedy about comics to be called “Convention Tension,” and moving to a second issue about the Aestheticist artist Aubrey Beardsley. Moore noted his gratitude “that Fantagraphics Books are being innovative or stupid enough to do a totally uncommercial package,” but for whatever reason the project never came together, and Moore’s association with Fantagraphics ended up being restricted to a couple of short pieces, of which “In Pictopia” is by some margin the most significant. [continued]

April 29, 2016 @ 3:43 pm

1) I’m surprisingly unsurprised, or perhaps unsurprisingly surprised, by your choice for the back-matter.

2) Also by the new tagline “Cuck the police”, on which the ambiguity is less. Will that internets be carry-out or delivery?

April 3, 2018 @ 5:57 am

Hi there! [url=http://onlinepharmacy.gdn/]online pharmacy[/url] excellent web page http://onlinepharmacy.gdn

April 4, 2018 @ 2:18 am

[url=https://onlinecasino24.us.com]online casino games[/url]

play slots online for money

online casino gambling

May 12, 2018 @ 4:31 pm

Hello! [url=http://canadianpharmacy.accountant/]canada pharmacies online prescriptions[/url] great website http://canadianpharmacy.accountant

December 4, 2018 @ 11:48 am

There are a massive variety of today s newest porn starlets waiting on you to watch them deepthroat some substantial dicks.

There are ladies doing several of the worst and also newest things around all for you to see at PORNOGRAPHY.

We have such a huge choice of videos here that you will certainly even have the ability to experience and check out some brand-new things that you never ever recognized that you enjoyed in the past.

[url=http://alhabib.info/]an adult movie[/url] types of oral sex oral sex for her only doggystyle good oral sex czech orgy hardcorre girls having sex giving the best blow job wanker how many women give oral sex pornovideos men performing oral sex on women shag realsex hollywood adult movie name

January 18, 2019 @ 7:29 am

I really wish Im useful in one way . Mac Os X 10.6 8 Download [url=https://www.miniwargaming.com/channel/compconc]https://www.miniwargaming.com/channel/compconc[/url].

Sparkasse Versicherung Iphone http://www.playtowerdefensegames.com/profiles/316822/fivoor.html. There is nothing to tell about myself really.

Great to be a member of this chat.

April 4, 2020 @ 5:30 am

Pplvhl mzeime coupon for cialis levitra vs cialis

November 23, 2020 @ 2:49 am

Ƭhe thermosgat or heating element ⅽould hаvе failed

and requirements replacement ߋr tһe dip tube cօuld bе damaged.

Үou can boost tһe efficiency of gas trouble

heaters ѡhile on аn insulation jacket. Tһeѕe systems heat the water by using passing water ᴡith

solar collectors սpon the roof of y᧐ur respective hߋmе.

April 29, 2016 @ 4:47 pm

inclined towards a “plague on all their houses” perspective that viewed everyone involved as being childish and overdramatic.

Ironically, that’s largely how Fleisher vs Ellison was presented where I first encountered it, in the pages of Ansible newszine. Court reporter Charles Platt placed himself on Fleisher’s side, while pointing out that, to the comicbook outsider on the jury there wasn’t much to choose between them (“So Ellison had described himself as crazy; and Fleisher had described himself as crazy; but the trouble started when Ellison said Fleisher was crazy.”) while editor Dave Langford added his sympathy for Ellison in a postscript.

The fact I read the Ansible story in 1998 or so makes this probably the first point where I have any previous knowledge of the War beyond having read the comics. I’m not entirely sure that it won’t be the last.

April 29, 2016 @ 7:04 pm

Surprised that you haven’t brought in Grant Morrison with the discussion of the Tyger, given his preoccupation with it in Zenith, for example.

April 30, 2016 @ 12:04 am

But this does not matter; one does not read Blake because the task will succeed. One reads his work for the same reason that he created it: because we have to. Because we are compelled.

Pretty much the same could be said of JS Bach. The more you listen, the more you realise there is to hear.

April 30, 2016 @ 8:57 am

[Jaime. Not Jamie.]

May 15, 2016 @ 3:56 pm

I was a big Fantagraphics buyer in the 80’s and 90’s when I was in my first comic buying spurt in my late teens/ twenties. They were pretty much my staple diet and I adored Love & Rockets (still do). Just ordered some of the early issues of Dodgem Logic I had missed – look forwards to seeing how that come up later on.

April 4, 2017 @ 3:28 am

As a BIG follower of this article, I was wondering if we’ll be seeing any more?

I’ve really enjoyed it up to now…

April 4, 2017 @ 8:33 pm

Yeah, it’s slightly back burnered until I get the next volume of TARDIS Eruditorum and the final version of Neoreaction a Basilisk out, so it’ll be a few months, but the project is definitely not abandoned. I’ll probably do the rest of Book Two like this, as one big post for each chapter with a couple months between posts, and then revert to weekly posts with Book Three.

April 9, 2017 @ 12:33 am

Oh thank God, I was quite worried. Your blog was a revelation for me, what with its focus on the three major interests of my life; being 1. Comic books (specifically, the good ones – though my tastes are broader and somewhat more forgiving than yours are, Phil), 2. Doctor Who (where I agree with you on almost everything, except for the quality of Season 6), and 3. Reconciling the two with one’s personal philosophy and maintaining a healthy life (still working on that last bit). It would have been heartbreaking if you’d just given up on the Last War. I need to hear your thoughts on All-Star Superman, even if it comes out alongside the tenth season of Sherlock. So, yeah, thanks for the update. Incidentally, while I’ve only so far read TARDIS Eruditorum in blog form, I’ll be buying the Mccoy book as soon as it’s out on shelves (as it’s the only “era” of Doctor Who so far that you’ll have covered that I’ve also watched in full).

June 13, 2017 @ 11:28 am

Like Cheshire I’m very much looking forward to further installments of The Last War!

“Watchmen” is probably the most extensively discussed comic of all time and I wonder whether this (besides Phil’s other writing commitments) hasn’t too played a part in slowing down the project…

I’m as big an admirer of “Watchmen” as other “Last War” readers but in a tiny way I’m looking forward to the completion of Book 2 and the beginning of Book 3! I’m a little bit more a fan of Grant Morrison than of Alan Moore and therefore I’ll also be glad once Morrison finally comes again into the project’s focus after an — inevitably — long hiatus!

October 30, 2018 @ 12:04 am

finished volume 1 last year and really enjoyed it, hope you come back to the project