I Asked Him What Record It Was, But He Didn’t Know (The Last War in Albion Book Two Part Twenty-Six: Olympus)

|

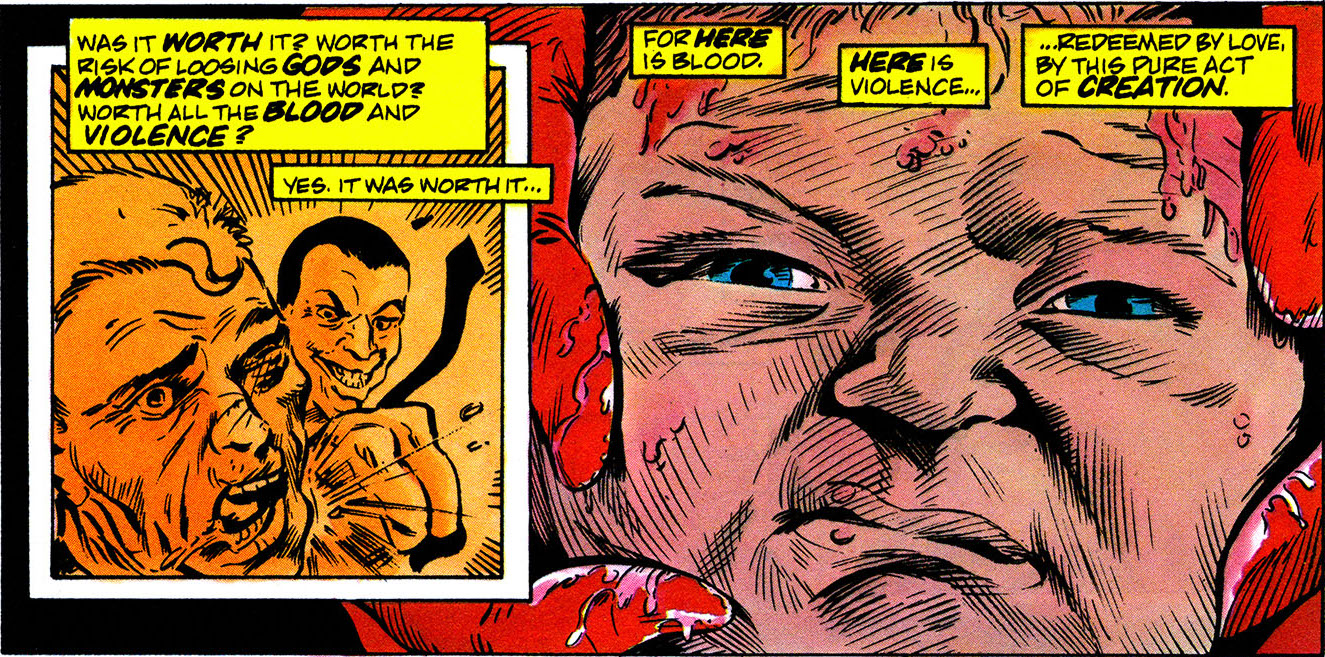

| Figure 930: Winter is worth it. (Written by Alan Moore, art by Rick Veitch and Rick Bryant, from Miracleman #9, 1986) |

Previously in The Last War in Albion: After a convoluted series of events, Alan Moore’s Marvelman, now renamed Miracleman, was published in the US by Eclipse, and Moore was writing new material for it, starting with a controversial issue including detailed images of Liz Moran giving birth.

As the sequence reaches its most famous page, it switches structure, the sepia-toned panels becoming insets on the full-color ones instead of the other way around as the baby’s head emerges. “Did it feel like this, when you took the first cell scrapings,” Miracleman asks the absent Gargunza. “Did it feel like this as you watched it divide and replicate; as you hauled me dripping from the tank? The head emerges; a face drawn on a fist. My eyes cannot grasp the fact of it: a head protruding from inside her. It looks so hideous, beautiful, absurd, awesome. But of course. Of course.” And finally, as Miracleman grasps his daughter’s head to finish delivering her, he asks, “was it worth it? Worth the risk of loosing gods and monsters on the world? Worth all the blood and violence? Yes. It was worth it. For here is blood. Here is violence. Redeemed by love, by this pure act of creation.”

|

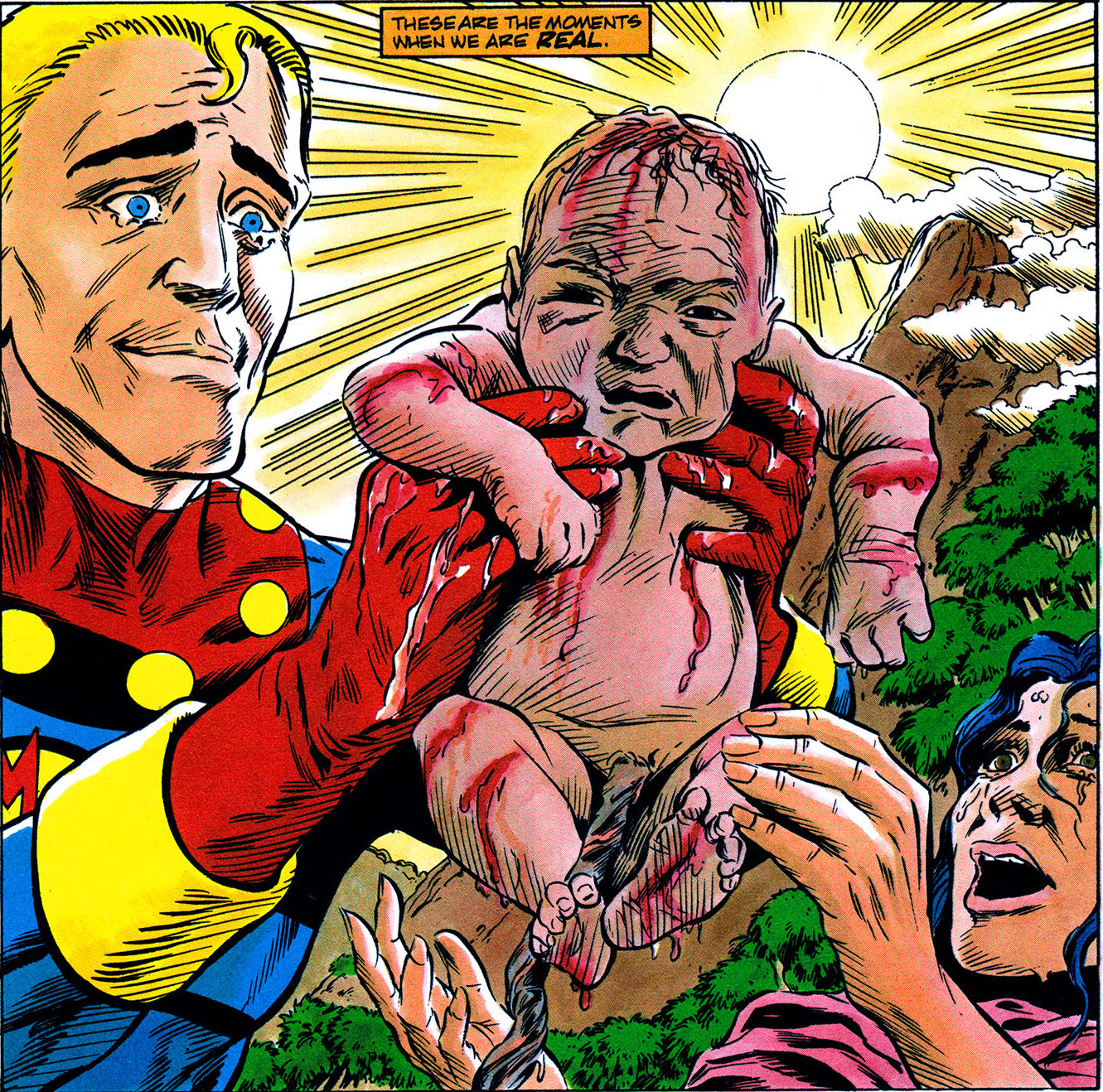

| Figure 931: Winter, delivered at last. (Written by Alan Moore, art by Rick Veitch and Rick Bryant, from Miracleman #9, 1986) |

It is, of course, a standard technique for Moore, right down to the heavily iambic flow of the narration. But the content is remarkable. It’s not that Moore hasn’t blended imagery of sex and death before, most obviously in “Rite of Spring,” where the orgasmic unity of all things includes a description of how “my enemy’s blood erupts to fill my mouth with molten copper,” but notes that “there is no contradiction” between this and sexual passion. Or, for that matter, in the description of the “almost sexual hatred” between Miracleman and Kid Miracleman in their early confrontation. But, of course, “Scenes from the Nativity” is not about sex, even though it contains the most detailed depiction of female genitalia to grace Moore’s work prior to Lost Girls. “Rite of Spring” stretched the definition of sex to its widest point, but stayed firmly within the realm of the erotic; “Scenes from the Nativity,” on the other hand, retains all the sense of taboo and sacredness, but strips it down to the most elemental binary, proclaiming that “in the careless and foggy continuum of our lives, these precious moments burn like suns: birth, death… these are the moments when we are real,” the final phrase coinciding with a 2/3 page panel of Miracleman and Liz crying as they hold the just-delivered Winter up to the gleaming sun. And in turn all of this is presented as the true and inevitable teleology of superheroes, with all of the ornately rewritten mythology of Miracleman being framed explicitly as something existing only to lead to this moment. It is, in short, a tour de force.

Veitch stayed for one further issue, rounding out Book Two of Miracleman (which had begun back in Warrior #13) with a story alternating between showing Mike and Liz’s new domestic life with their slightly unsettling new child and two mysterious figures speaking a strange alien language looking for the “cuckoos,” who are clearly the subjects of Gargunza’s experiements (including a previously unseen woman who flees before they can find her, marking the introduction of Miraclewoman). But whereas first nine issues had come out more or less monthly, with no more than a two month gap between them, Miracleman #10 came out in December of 1986, five months after “Scenes from the Nativity.” Gaps of this size would remain the norm for the remainder of Moore’s run on the title, as well as for Neil Gaiman’s follow-up, with more than a year separating Moore’s last two issues.

Part of the reason for these delays was that the artist on the final six-issue stretch of Moore’s run, John Totleben (who, like Veitch, came over from Moore’s Swamp Thing work), was diagnosed with a degenerative eye condition shortly before he began work on the series, which slowed his work considerably. But given that the scheduling difficulties continued even after Gaiman and Buckingham took over the title, it is difficult not to assume that Gaiman’s explanation of the delays applied to his predecessors as well. As Gaiman puts it, “the bit nobody ever knew was that we wouldn’t start writing until we got paid for the last episode. I would stop writing and Mark wouldn’t start drawing. It wasn’t that we were a year late. It was like one day our checks would turn up and then we start working on it because the checks were so amazingly unpredictable from these guys. We didn’t realize at the time that they were being creative with the royalties, all the stuff that wound up[ sending them into bankruptcy.”

|

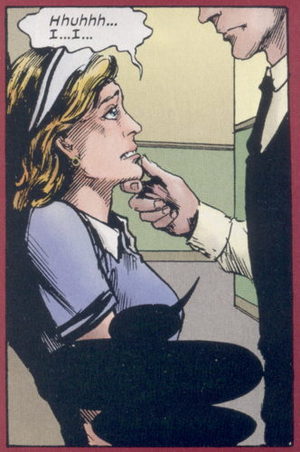

| Figure 932: Miracleman #14, misprinted by Marvel in their 2015 reprint. (Written by Alan Moore, art by John Totleben, original 1988, colored by Steve Oliff 2015) |

Adding to the frustration for readers was the rapidly increasing price of the issues. When the Eclipse series had launched in 1985 it had been priced at ¢75, the industry standard price shared by Swamp Thing. With issue #5 it jumped to ¢95, a modest increase, especially given that as of issue #9 the actual Miracleman material was reduced to a mere sixteen pages per issue, with a Laser Eraser & Pressbutton strip usually making up the rest of the issue. But with the start of the John Totleben issues the price jumped again to $1.25, and, two issues later, to $1.75. Both of these increases coincided with larger jumps in the industry, but it was difficult not to feel that $1.75 was rather a lot to spend for Miracleman #13, which didn’t even feature new material in its backup strips, instead reprinting a pair of Mick Anglo stories on top of its meager sixteen pages of new content. (Although the all-time record for appalling pricing is held by Marvel’s 2014 reprint of issue #14, which cost $4.99, padded the sixteen page story out with reproductions of Totleben’s pencilled art, some figure studies, and a Mick Anglo reprint, and managed to misprint the issue so that one of its most famous scenes lacked any dialogue, then declined to offer a reprint.)

|

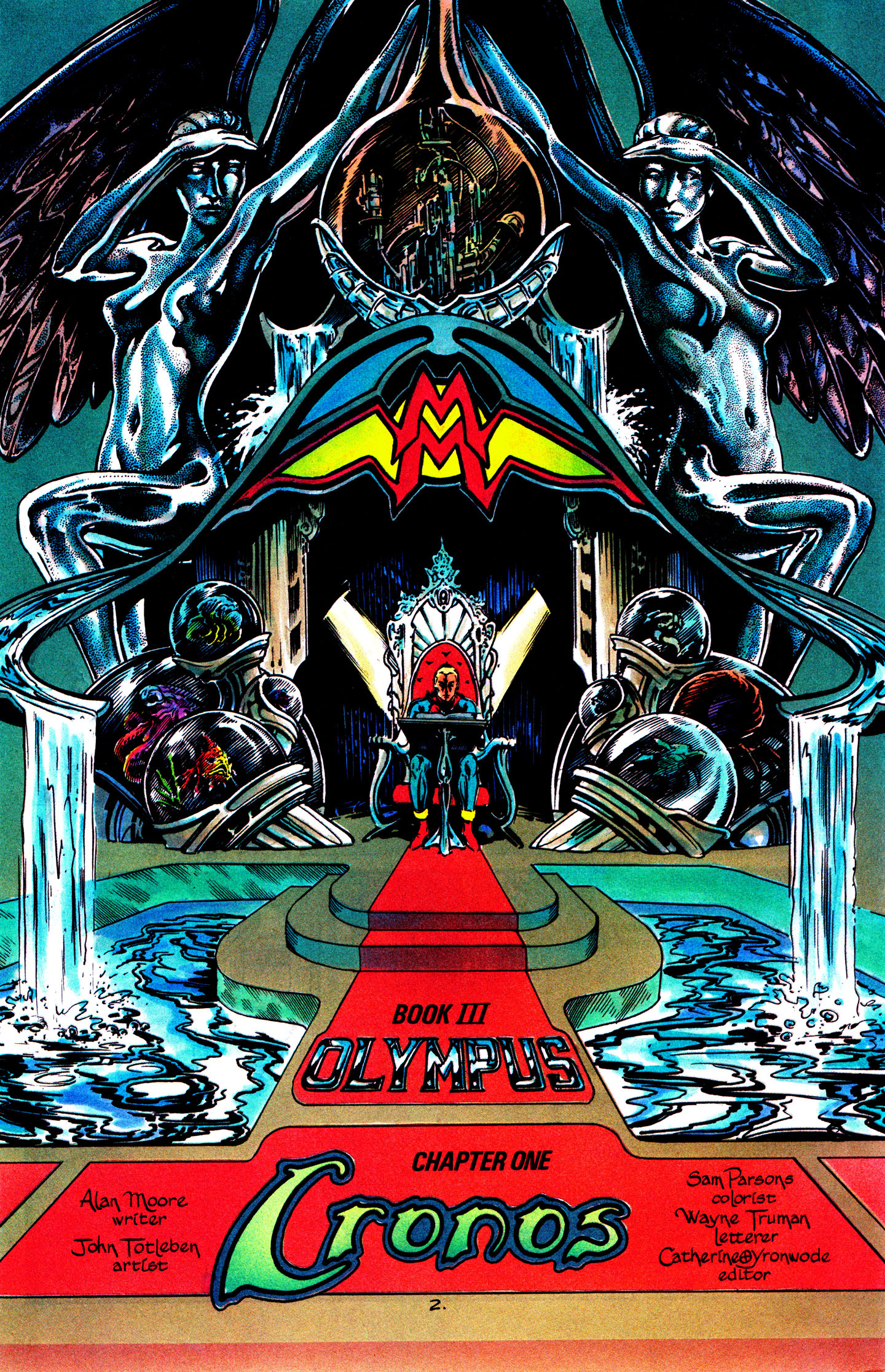

| Figure 933: Miracleman’s opulent and alien throne. (From Miracleman #11, 1987) |

Given all of this, it’s hardly surprising that when Moore called Neil Gaiman around the time of Miracleman #10’s publication to offer him the opportunity to continue the series Moore described it as a “poisoned chalice.” But in some ways his more interesting warning came after Gaiman expressed interest when, in Gaiman’s telling, he said “now I should warn you by the end of Miracleman #16 I will have solved all crimes, ended all war, and created an absolutely perfect world in which no further stories can occur. Do you want to back out now? Please feel free.” Indeed, although the means by which this happens are not fully revealed until Moore’s final issue, this radical state of affairs is introduced at the start of Miracleman #11, which jumps five years forward from the 1982 setting of the main story to 1987. This is a sly move on Moore’s part; 1982, of course, had been the present day when the series debuted in Warrior, and the five year time jump brought it to the present day. But whereas “A Dream of Flying” took place in a 1982 that was, at first glance, the same as one it was published into, “Cronos,” the first part of Book III, also titled Olympus, opens with Miracleman in a vast palace of crystal inscribing “tales of how it feels to live in a mythology” into a book made of steel while sitting upon a throne adorned with beautiful metal statues and strange alien flora and fauna. All but three of the sixteen pages consist of his tales, a flashback to 1982 that picks up where Miracleman #10 left off, but over the course of those three pages it becomes increasingly clear that Miracleman is in fact ruling the entire planet. Instead of starting from the world of the reader and slowly twisting it into something new, Moore was now presenting a world that was radically unlike that of the present day, even as he asserted that it took place there, twisting the premise so that it began from the alien instead of from the human.

|

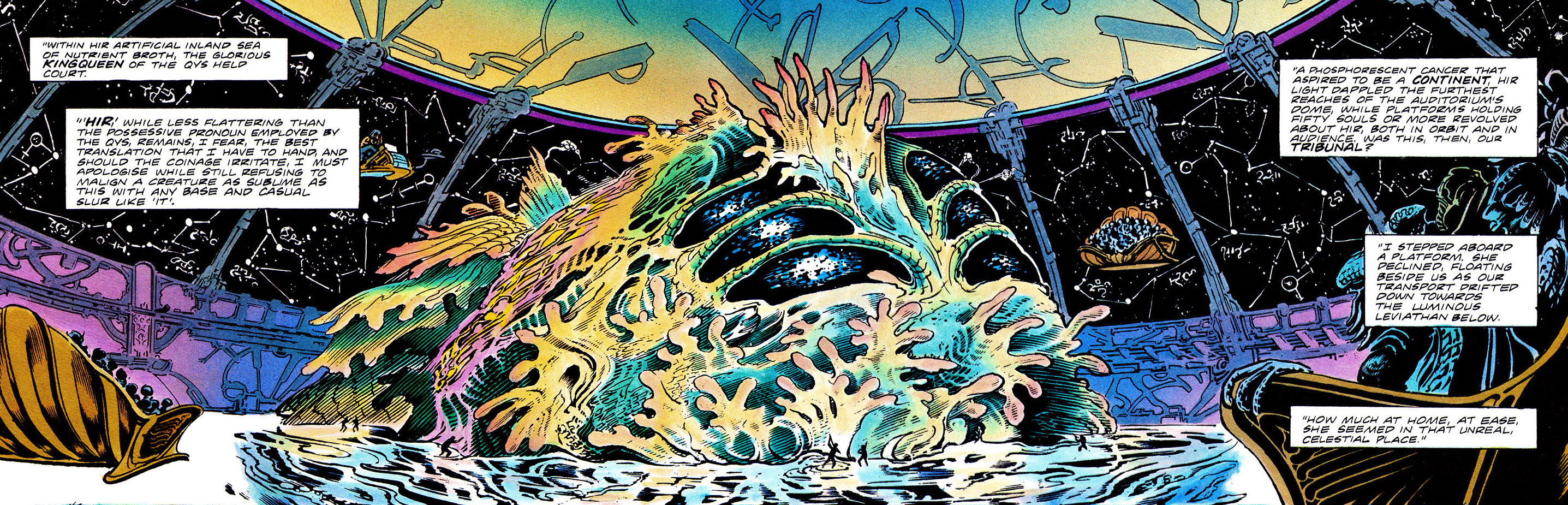

| Figure 934: The Kingqueen of the Qys. (Written by Alan Moore, art by John Totleben, from Miracleman #13, 1987) |

This is reflected throughout the Olympus arc, which uses the 1987 frame story for each of its first four installments. But more broadly, it is reflected in the focus of the arc, which moves from untangling Moore’s reimagining of Mick Anglo’s original mythology to exploring the worlds of the alien races that Moore established as the true origins of the character. In some ways this is a mixed bag; the space-bending Warpsmiths and body-swapping Qys are interesting concepts, and Totleben’s depiction of them, heavily indebted to classic pulp illustrator Virgil Finlay, is at once lush and unsettling, living up to Moore’s description of “a phosphorescent cancer that aspired to be a continent, hir light dappled the furthest reaches of the auditorium’s dome, while platforms holding fifty souls or more revolved around hir, both in orbit and in audience,” as he has Miracleman describe the Kingqueen of the Qys. But with as many other plot threads as Moore is juggling through the four sixteen-page installments leading up to his denouement, their development is scant, and they never really progress beyond being interesting ideas, a tendency exemplified when a discussion of whether the Warpsmiths and Qys are necessarily locked into an endless cycle of war is resolved by Miraclewoman casually suggesting “couldn’t you have sex instead” and explaining that “if two organisms or two cultures are forced into contact it can be thanatic and destructive, or erotic and creative,” an observation that basically fixes everything.

|

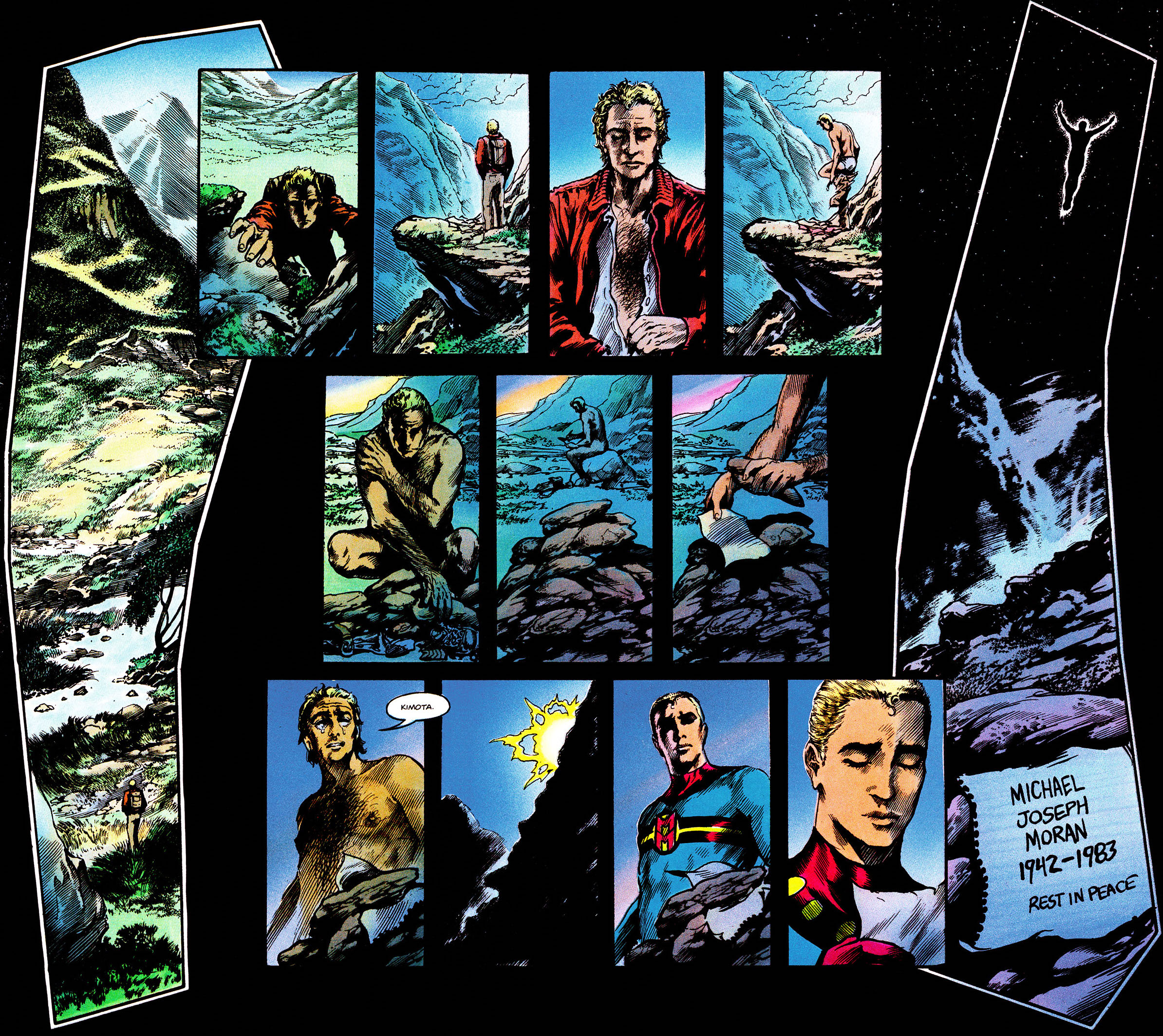

| Figure 935: The death of Michael Moran. (Written by Alan Moore, art by John Totleben, from Miracleman #14, 1988) |

That is not to say there are not impressive moments in these issues, most obviously a two-page sequence in Miracleman #14 in which Mike Moran travels to Scotland, climbs a mountain, strips, buries his clothes beneath a small cairn, and then places a scrap of paper atop it before saying his magic word for the last time. Miracleman picks up the scrap of paper and reads it before flying away, with the final panel revealing its contents to the reader: “Michael Joseph Moran 1942-1983.” And the stories of behind-the-scenes drama pile up as well, most notably a panel in issue #12 in which Young Nastyman commits necrophilia, a moment that’s relatively subtle in the issue itself, but that in the script was, as Totleben fondly recalls, “a real howl. It was incredibly graphic and excessively lurid. I think maybe he was going a bit over the top just to antagonize them or something,” leading to a lengthy conference call with Totleben over it in which he shocked Dean Mullaney by declaring that he was not particularly bothered by drawing the panel, pointing out that Moore had called for a very large panel of Miraclewoman in classic William Moulton Marston-style bondage and that very little of Moore’s detail would actually be able to make it into the panel.

|

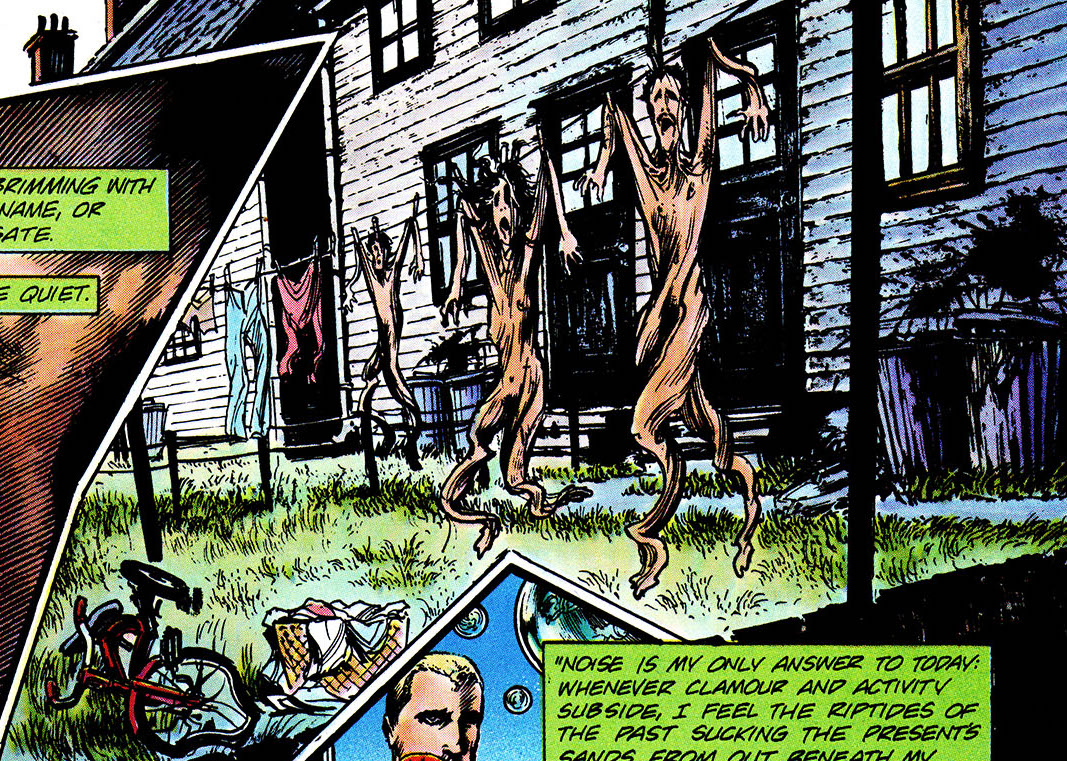

| Figure 936: Miracleman #15 starts as it means to go on – with a clothesline of human skins. (Written by Alan Moore, art by John Totleben, 1988) |

But for the most part these four issues are mere preludes to Miracleman #15, which rivals issue #9 in terms of its impact and infamy for reasons that are at once similar and radically different. The issue deals with the return of Kid Miracleman, who finally escaped the prison of Johnny Bates’s mind at the end of the previous issue when Bates was sexually assaulted by other children at the hospital and tearfully and desperately used his word. (This results in the iconic scene in issue #14 that Marvel subsequently misprinted the dialogue of in which Kid Miracleman informs a nurse, “you were the only one who was kind to me” and declares that he’ll let her live, walking off, then doubling back and saying, “I’m sorry. They’d say I was going soft, wouldn’t they” and vaporizing her skull, a scene notably ripped off almost note for note a quarter-century later by television writer Toby Whithouse in Being Human.) It is an interesting question exactly when Moore decided on this resolution and its consequential establishment of a utopian society under Miracleman’s authority. His original outline pitching his ideas to Dez Skinn had left off with the Gargunza storyline that made up Book Two and a vague description of “an encounter with the alien race whose starship fell to Earth in Wiltshire all those decades ago.” But he clearly had some idea along these lines by the time of 1982’s Warrior #4, for which he penned “The Yesterday Gambit,” which presented itself as a flash forward in Miracleman’s timeline and included the Warpsmiths, the return of Kid Miracleman, and Miracleman’s underwater fortress Silence, all of which feature in Miracleman #15, although in forms that are not entirely compatible with “The Yesterday Gambit,” which was the one Marveleman story from Warrior that Eclipse declined to reprint. (Despite this, Moore references its events directly in issue #15, positioning them as one of the many apocryphal legends of the fight, “each with its own adherents; as valid, if not more so, as the truth.”)

|

| Figure 937: Bates in a more light-hearted presentation from early in the story. (Written by Alan Moore, art by Gary Leach, originally printed in Warrior #5, 1982, colored for Miracleman #2, 1985) |

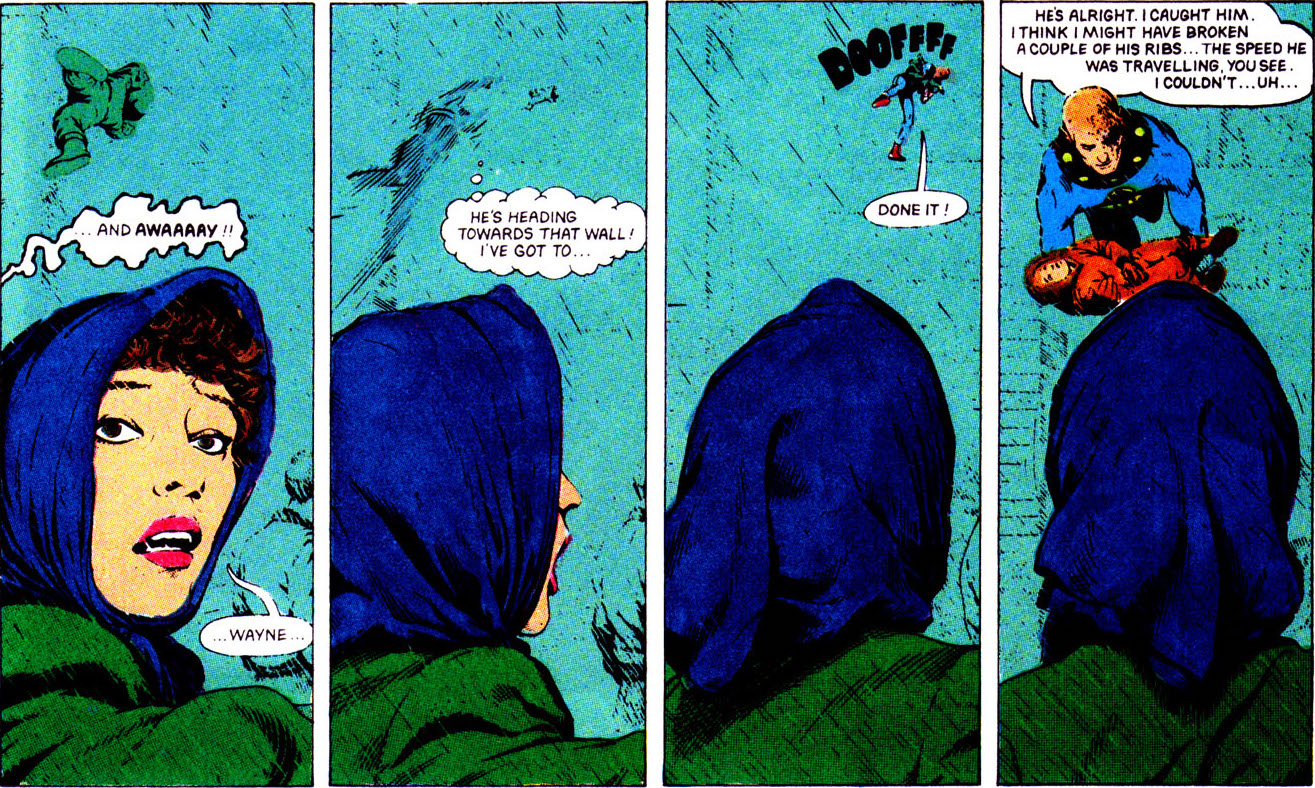

But nothing in “The Yesterday Gambit” hints at the shocking brutality of Miracleman #15. Moore’s explanation for the issue was wanting to “show a superhero fight as it really might be. Let’s just show how bad it might really get if you had Superman and Bizarro punching out in downtown Metropolis.” Moore had grappled with some of this in the first Miracleman/Kid Miracleman fight when, for instance, Kid Miracleman hurls a baby through the air in the middle of the fight, distracting Miracleman by throwing a baby at a nearby building, which Miracleman of course saves, but with the note that he’s broken a couple of the baby’s ribs because of the speed he was traveling, a grimly funny note of realism in a standard superhero trope. There’s a not entirely dissimilar moment in Miracleman #15 when Miracleman, in another fairly standard superhero punch-up moment, picks up a car and throws it at Kid Miracleman. “My apologists have claimed the car that I first hurled at Bates was empty, those who’d been inside having all previously escaped,” he narrates.

February 12, 2016 @ 11:03 pm

“Totleben […] was diagnosed with a degenerative eye condition shortly before he began work on the series, which slowed his work considerably.”

And also put the kibosh on Hellhead (initially announced as The Ironic Man), which would’ve been the only component of Rick Veitch’s King Hell Heroica that Roarin’ Rick did not himself draw. (In the final issue of the Bratpack comic, there’s a mention of Hellhead‘s main characters, Scourge and Runamok, but the redrawn ending of the graphic novel removes this.) I mention it here in a probably-futile effort to get our host to reconsider covering the Heroica as part of the War.

February 15, 2016 @ 8:52 pm

Love figure 993.

February 17, 2016 @ 7:59 pm

I mean 933!

February 17, 2016 @ 12:00 am

My favorite story regarding the delays comes from ‘The Miracleman Companion’, by TwoMorrows Press. There’s an interview with Cat Yronwode where she talks about how “unreliable” Gaiman and Buckingham were, and how she didn’t want to get into the nasty details but there was all sorts of personal stuff that was affecting their ability to work.

Then about forty pages later there’s an interview with Gaiman where he quite casually mentions that he and Buckingham wouldn’t start work on the next issue until they’d been paid for the last one. It was the most quietly beautiful demolishing of a self-interested narrative I’d ever seen. 🙂

September 5, 2016 @ 7:26 am

Mr. Christian Louboutin brand of the same name was founded in 1992 in Paris, the talented shoe designer collection of artists and craftsmen in one shoe, with immense passion for footwear design, to create an unlimited number of unique colorful design, red lacquered soles it is to become the trademark of the world’s top footwear brand cheap christian louboutin design. Different geographical culture has become a source of inspiration of Christian Louboutin, and into the ideas are like the design of making more diverse style of footwear. Born in Paris since the beginning, beautiful red soled cheap christian louboutin shoes with his own traveled all over the world, free from the avant-garde New York, London, elegant and refined, mysterious ancient Egypt and India, and then to Hawaii passionate fusion of classical and modern Beijing, the “Paris of the Orient,” said the Shanghai, can find the classic Christian Louboutin red in these cities.more at:http://www.christianshoesukshop.co.uk