Lost Exegesis (Solitary) — Part 1

We now begin what I consider to be the second act of LOST’s first season. The basic tenor of the show has now been laid out – our principal characters have been introduced in some detail, as has the mysteriousness of the Island, and the general tenor of the show’s approach to episodic serialization has been established. Overall, it’s been a story of how these survivors of a plane crash have adapted to living on an island in the South Pacific, touching on issues of social organization through intense characterization. Now the show begins to shift focus, adding new dimensions: not only will some of the mysteries introduced early on be revealed, but it starts exploring the implication of the fact that our survivors are not alone.

We now begin what I consider to be the second act of LOST’s first season. The basic tenor of the show has now been laid out – our principal characters have been introduced in some detail, as has the mysteriousness of the Island, and the general tenor of the show’s approach to episodic serialization has been established. Overall, it’s been a story of how these survivors of a plane crash have adapted to living on an island in the South Pacific, touching on issues of social organization through intense characterization. Now the show begins to shift focus, adding new dimensions: not only will some of the mysteries introduced early on be revealed, but it starts exploring the implication of the fact that our survivors are not alone.

Which is ironic, given the title of the episode. And yet, in some ways the title of this episode is perfectly chosen, given the extent to which it explores the various connotations of the word and some of its metaphorical implications. We have Sayid, of course, who has shunned his fellow survivors out of his own shame; we have Rousseau, who lives the life of a hermit; we have Nadia, who experiences solitary confinement; we have Sawyer, a self-described outcast; we have Walt, estranged from his father; we even have the game of golf, which is most typically (though not exclusively) played as individuals competing against others or themselves, unlike most sports, which are team affairs. And, of course, there’s the fact that our Losties are literally lost on an Island, itself a solitary and unique place.

Let’s start with Sayid. It’s interesting that we begin this episode right where the previous one left off – indeed, the end of Confidence Man is prophetic, with Sayid heading off to ostensibly “map the Island,” which is practically what we get in Solitary. We haven’t had this much continuity between episodes since Pilot Part 1 and Pilot Part 2, with a dash of Tabula Rasa thrown in. We also haven’t had a character who blatantly represents a major component of the audience’s desire regarding the show’s mysteries. Jack is concerned with leading the group, Charlie with facing his demons, Kate with proving she’s a good person, Sawyer with proving he’s not, and all the rest with their own interpersonal relationships. Locke comes close, but he’s already had his revelation, an experience not shared by the audience. Sayid, on the other hand, has already tried to triangulate the source of the Frenchwoman’s transmission, and now he’s actively exploring the Island. He is now, at least here, our proxy for trying to divine the Island’s mysteries – especially once he finds a mysterious cord laid out across the beach, leading at once out to sea and deep into the jungle.

The Hanged Man

As such, I find it very interesting that Sayid eventually finds himself in a position that evokes a couple of mythological connotations when he ends up caught in Rousseau’s trap, hanging upside down with his leg briefly impaled by a pointy stick. This final point suggests a particular myth, namely the myth of Odin from the Poetic Edda:

“I know that I hung on a windy tree nine long nights, wounded with a spear, dedicated to Odin, myself to myself, on that tree of which no man knows from where its roots run. No bread did they give me nor a drink from a horn, downwards I peered; I took up the runes, screaming I took them, then I fell back from there.”

In this myth, the god Odin has sacrificed himself to the World Tree, the axis mundi that runs through the worlds, connecting Above and Below, Past and Future, to the Here and Now. He’s been impaled, and he peers downward, towards the ground. His reward is the gift of the runes, of writing. In other words, this is a spiritual quest, one of gaining wisdom in the act of ego-death. Which, for Sayid, is actually apt. When he hangs from the tree, he prays – he frames his entrapment with a spiritual context. He is impaled, and looking downward. At the end of the episode, he gains certain writings – not words, per se, but the written maps that Rousseau has produced – in accordance with the “quest” he set out to accomplish at the end of the previous episode.

I want to tease out some of the mythological connotations here, if only for future reference. In Norse mythology, the World Tree is called Yggdrasil, and it’s under the branches of Yggdrasil that the last two humans escape Ragnarok, the end of the world, the apocalypse. This will have implications for future readings of LOST, and suggests something of the nature of the Island. And then we have Odin, a god who sacrificed his right eye to learn all the past, present, and future – to become an all-seeing Eye, which plays into the opening salvo of Eye imagery in LOST. For Odin, though, the experience must be like one of being outside of Time itself, where everything happens at all once, and Fate is thus immutable. Imagine Billy Pilgrim, from Slaughterhouse Five by Kurt Vonnegut, who gains a glimpse of such a perspective. Finally, there’s a metatextual implication, namely that to learn of “the writing” plays back into Sayid’s role as an audience proxy at this point: for those of us interested in gleaning the Island’s mysteries, an understanding of the principles that underlie the writing of the show would surely be paramount. Indeed, this is partly why the Lost Exegesis favors an intertextual approach.

I’m also reminded of Wagner’s Ring Cycle, which features the god Odin (Wotan) in his effort to save Frei, the goddess of beauty and love and youth, by recovering a magic ring of power forged in the renunciation of love. This, however, will have to wait for the Intermission in next week’s essay.

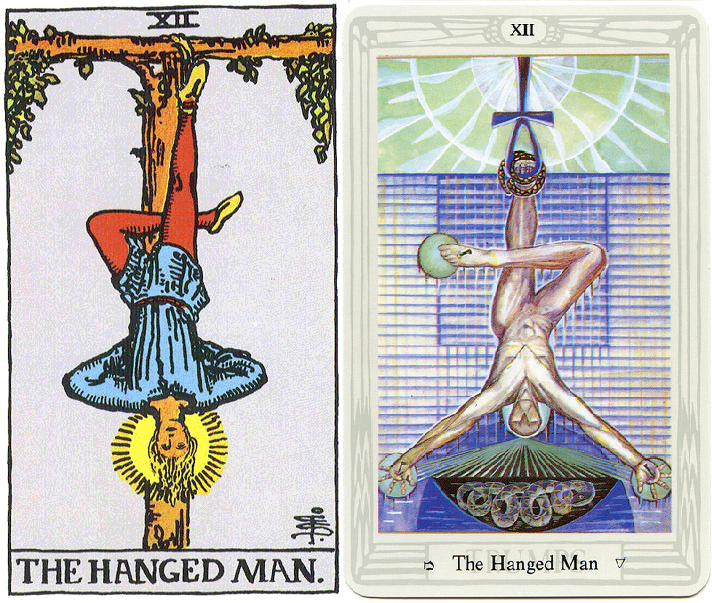

The other esoteric connotation to note of Sayid’s position is that of The Hanged Man, from the Tarot. The most widespread Tarot images are those of the Rider-Waite deck, drawn by Pamela Coleman Smith, and Aleister Crowley’s Thoth deck, drawn by Lady Frieda Harris. The 12th card in the Major Arcana (well, the 13th, given the position of The Fool as 0th card), the Hanged Man comes between Justice (11) and Death (13). It is typically interpreted to indicate a time of reflection, a relationship between the Divine and the Universe, even a moment of initiation. Alternatively, it represents inaction and suspension, the inability to go forward, even the dark night of the soul. In context between Justice and Death, it should not be surprising that very early versions of the card called him The Traitor.

The other esoteric connotation to note of Sayid’s position is that of The Hanged Man, from the Tarot. The most widespread Tarot images are those of the Rider-Waite deck, drawn by Pamela Coleman Smith, and Aleister Crowley’s Thoth deck, drawn by Lady Frieda Harris. The 12th card in the Major Arcana (well, the 13th, given the position of The Fool as 0th card), the Hanged Man comes between Justice (11) and Death (13). It is typically interpreted to indicate a time of reflection, a relationship between the Divine and the Universe, even a moment of initiation. Alternatively, it represents inaction and suspension, the inability to go forward, even the dark night of the soul. In context between Justice and Death, it should not be surprising that very early versions of the card called him The Traitor.

These descriptions are apt for Sayid. He’s trying to run away from his people, but he’s stopped in his tracks. He’s a traitor, at least to the Republican Guard, and certainly to his own ideals. And he’s about to be initiated into certain Island mysteries.

Unlike the tale of Odin, however, which exists in but a singular form from the Poetic Edda as saved in the Codex Regius, the images of the Tarot have changed throughout the centuries; indeed, the very practice and intention of Tarot does not have a singular canonical expression or source. We can trace their origin back to Italy, but as playing cards for very rich families, with any esoteric messages most likely rooted in politics, social commentary, or vanity. By the 18th century, the use of playing cards for gaming was widespread, but even then the art cartomancy – using the cards for divinatory practice – had grown, alongside other kinds of “random” practices like throwing dice or casting sticks, not to mention palmistry and astrology. At this point a fairly standard order emerged for the Major Arcana when it came to the Tarot, from the French woodcuts of the Tarot de Marseilles. It’s from this deck that hermetic, alchemical interpretations of Antoine Court de Gébelin introduced the use of Tarot not as a vehicle for games or divination, but as a subject of esoteric study in its own right. This in turn led thinkers like Jean-Baptiste Alliette (known as Etteilla, a simple mirroring of his last name) and Alphonse Constant (known as Eliphas Lévi) to design their own decks and link the Tarot to astrology, the elements, the Kabalah, and other occult understandings. This, in turn, is what led Arthur E Waite and Pamela Coleman Smith, adepts of the Hermetic Order of the Golden Dawn, to publish through Rider their own deck, and which in turn led to Crowley and Harris’s own ideas.

This is why so many decks have different takes on the images. In the Marseilles, we find Justice and Strength as the 8th and 11th trumps, but the Waite-Smith deck reverses them, and the Crowley-Harris deck reverses that reversal back. And, of course, the imagery itself differs. With the Waite-Smith deck, we see the Hanged Man hanging from his right foot, upon a Tau-shaped living tree (no ordinary gallows here), his hands pinned behind him, the leg crossed over in a fylfot cross. Crowley-Harris have him hanging from his left foot, attached to an Egyptian anhk via a snake, above a much larger snake, and his hands staked in way that evokes a sense of crucifixion. But the earliest images of the Hanged Man do not have these connotations – it’s simply a man hanging from his feet at a standard gallows.

Indeed, when Etteilla first reworked his rather unconventional deck back in 1789, he significantly reordered and renamed a number of cards; his version of The Hanged Man becomes Prudence, an interpretation based on holding the card upside down and seeing someone stepping gingerly over a snake. It’s interesting, then, that even this sense of the card is retained by Sayid when he gingerly steps over the tripwire in the jungle, only to land in a trap.

So, in the spirt of the ever-changing Tarot, let’s examine the particulars of LOST’s version of the Hanged Man in its own context. We’ve already considered his impalement, connoting the tale of Odin. Next, Sayid’s legs are not crossed at all – instead he hangs in an X pattern, a pattern we’ve already discussed in relation to the paths of Charlie and Liam back in The Moth—the X symbolizes finding the right spot, crossing trajectories, and the union of opposites, marking change and transformation. Uniquely, he hangs in the Jungle, now a place of Mystery.

It’ll be interesting to see if Tarot cards appear again in LOST.

Par for the Course

Par for the Course

Speaking of games, there’s this whole thread in the episode about Hurley building a golf course. It is, of course, a necessary tonic considering the rather intense nature of Sayid’s ordeal at the hands of the Frenchwoman, coupled with his rather intense FlashBacks of Nadia. So before we launch into Sayid’s tale, let’s consider and appreciate the apparent levity of these sequences. We should note, first of all, that the golf clubs are found by a new character, Ethan, who was out hunting “rabbit” with Locke and found them before dumping them at Hurley’s feet. Given our obsession Watership Down and following “the White Rabbit” down the rabbit hole (invoking Alice’s adventures in Wonderland and Through the Looking Glass), I do not think this is a sequence that should be casually dismissed. Hell, the whole point of golf is get a little white ball (the rabbit) into a cup in the ground (the rabbit hole) that is marked with a little flagpole (the axis mundi).

As mentioned before, golf is typically a solitary sport. It’s a game you can play all by yourself, and most competitions are structured as individual pursuits. True, there are team versions of the game, but even when played as a team, only one player is playing at any given time; everyone else hangs out and waits. Every stroke is made singularly.

And yet, with Hurley in charge, the game becomes a communal adventure. People from both the Caves and the Beach (representing the schism in philosophies amongst the survivors) come together upon mountains green, to watch the game be played in the spirit of teamwork – Jack and Michael face off against Hurley and Charlie. Even loners like Kate and Sawyer show up – and Sawyer gets into the spirit of the game by making a bet, a wager, about whether Jack will make his shot or not, a shot we never get to see.

HURLEY: (after grounding his club into the turf, completely missing the ball) Aw, crap, do over.

CHARLIE: It’s a mulligan, mulligan. It’s a gentleman’s sport, you’ve got to get the words right. Mulligan.

There’s an interesting word that’s repeated during the golf game: Mulligan. It starts when Hurley completely misses the ball, and wants a “do over.” Charlie corrects him with the “correct” terminology. Mind you, in the official rules of golf, there are no do-overs, no mulligans. This is a casual convention. And yet Charlie is right: it’s certainly gentlemanly. Everyone pretends that the original errant shot didn’t happen, and the subsequent shot represents the true story.

Regardless, not unlike the Tarot, there are multiple origins for this practice. In one version, it was a Canadian, David Mulligan, who re-teed a ball after a poor drive (possibly due to bad nerves after a rushed or difficult trip to the golf course that morning) and called it a “correction shot.” In another version, it was John “Buddy” Mulligan who got an extra shot from his buddies Dave O’Connell and Des Sullivan, on account that they had practiced all morning while he was working.

Interestingly, there was once a single-prop airplane from around that time called “Mister Mulligan,” that won a couple of cross-country trophies in 1935. However, in 1936, the plane crashed in New Mexico, and pilot Ben Howard not only lost his leg, he lost the airplane. It was found in 1970 by racing enthusiast Bob Reichardt, who salvaged most of the parts and gave Mister Mulligan a second life. Alternatively, we might consider the fictional character of Malachi “Buck” Mulligan, from James Joyce’s novel Ulysses. At once callous and complex, Mulligan is a Falstaffian student of medicine, portrayed as both offensive and heroic, having saved a man from drowning. He is the subject of the novel’s first sentence: “Stately, plump Buck Mulligan came from the stairhead, bearing a bowl of lather on which a mirror and a razor lay crossed,” from which he parodies the Mass. He comes across as a combination of Hurley, Jack, and Sawyer. Perhaps if Ulysses appears in LOST at some point, we’ll return to this text.

In the meantime, we’ll go back to the obviously intended meaning of “mulligan” within the text of LOST, that of the “do-over.” It is, in other words, the chance to have a fresh start. A clean slate. At its best, it means life renewed. It’s a form of resurrection, a way to “go back.” This is the second game presented in LOST, and this emphasis on going back evokes the first game, Backgammon, which has going back as an integral mechanic of its rules. Interesting, though, that a mulligan – the ability to go back for a do over, to cover up something too terrible to behold – is only necessary after a mistake, after failure, after your shot has died.

The Mirror Box

The Mirror Box

SAYID: Danielle, please let me go.

DANIELLE: Go?

(The music box dies, grinding to a halt.)

SAYID: Back to the people I told you about.

One of the things LOST really excels at is developing all kinds of interesting and unique metaphors for what’s going on with our characters, and how they’re progressing through their issues. Danielle Rousseau’s music box is one of those metaphors. Embedded in the hinged lid of the music box is a triptych of mirrors, making this a reflection of Danielle and her heart. When the episode begins, she is broken, just like her music box. But when Sayid opens the music box to work on it, he also goes to work on fixing Danielle, who subsequently opens up.

He starts by asking questions – by asking her for her name, her first name. “Danielle” is the feminized version of Daniel, a Hebrew name which means “God is my Judge.” Daniel was a prophet in the Old Testament; within the text of LOST, Danielle serves as a prophet, describing events future to the text but from the past in her own narrative.

Anyways, Danielle opens up. She talks about her lost love, Robert. And she describes how she came to the Island. Like with the plane crash, it involved malfunctioning instruments, and the crash of the vehicle, though she came by boat rather than by plane. And then we get what seems to be a major clue – Danielle says there are “others” on the Island. She’s heard them. Heard them whisper. Sayid doesn’t believe her, but prophets are often not believed; Sayid will hear Whispers at the end of the episode.

The funny thing is, this scene reflects an earlier scene in the episode. When Danielle finds Sayid’s envelope, the one with the pictures of Nadia in it, and opens it up, Sayid starts opening up to Danielle. He speaks of his lost love, and how he came to be on the Island. He talks of being alone, out of shame for what he’s done. He opens up his heart, in other words.

In fact, there’s a rather remarkable amount of “mirror-twinning” in the dialogue between Sayid and Danielle:

SAYID: Rousseau.

DANIELLE: How do you know my name?

SAYID: I read it. There, on the jacket. What is this place? Those batteries — they wouldn’t be able to produce enough power to transmit your distress call all these years.

DANIELLE: It broadcasts from somewhere else. But they control it now.

SAYID: They?

DANIELLE: You. And the others like you.

SAYID: I don’t know who you think I am. I’ve already told you I’m not…

DANIELLE: Sayid?

SAYID: How do you know my name?

DANIELLE: My name was on a jacket, yours is on the envelope you carry.

It’s almost a dance. Sayid reads her name on a jacket – an outer covering – and she reads his on an envelope, likewise. Even the structure of the moment is mirrored: the name read aloud, the question of “How do you know my name?” and the answer to that question.

SAYID: I found a wire on the beach, I followed it. I thought it might have something to do with the transmission we picked up on our receiver. A recording, a mayday, with a French woman repeating on a loop for sixteen years.

DANIELLE: Si quelqu’un m’entend, je vous en prie, venez à notre aide… Il les a tués. Il les a tous tués… Sixteen years. Has it really been that long?

SAYID: You.

DANIELLE: You just happened to hear my distress call?

In this scene, Sayid mentions the maydays that’s been on a loop for sixteen years. Danielle then repeats one of the lines from that distress call: If anybody hears me, please, come to our rescue… It killed them. It killed them ALL. (This line will be repeated later on by Sayid: “Your distress signal? The message I heard, you said, ‘It killed them all.’”) Danielle then repeats Sayid’s last words, “sixteen years.” When Sayid gasps “You,” her very next sentence begins with “You.”

DANIELLE: We were coming back from the Black Rock. It was them. They were the carriers.

SAYID: Who were the carriers?

DANIELLE: The others.

SAYID: What others? What is the Black Rock?

Notice the quick repetition of “the Black Rock,” “the carriers,” and “others.”

DANIELLE: You can’t. You have to stay. It’s not safe.

SAYID: Not safe, what’s not safe?

DANIELLE: You need me! You can’t leave.

SAYID: Danielle… Where are you going?

DANIELLE: If we’re lucky, it’s one of the bears.

SAYID: If we’re lucky? It might be that thing out there — the monster.

DANIELLE: There’s no such thing as monsters.

And again with “not safe,” “if we’re lucky,” and “monster.” This is exactly the same phenomenon we noted in Pilot Part 2, but here it’s only between Sayid and Rousseau. In Sayid’s FlashBacks, the dialogue isn’t filled with repetition, is neither is the side plot involving Hurley’s golf course. However, there are some strange resonances with what’s going on in their interactions.

I described this as a dance (take a lot at Rousseau’s music box again) and it comes to a mirrored climax when Sayid and Danielle point rifles at each other, each taking exactly the same position and stance as the other. Sayid says he doesn’t want to hurt her; she retorts that he already has, a reversal. When Sayid pulls the trigger, nothing happens, and Danielle notes that Robert didn’t notice when the firing pin had been removed either – this scene has happened before, in Danielle’s experience. Danielle says he was sick; Sayid claims he is not sick…

I described this as a dance (take a lot at Rousseau’s music box again) and it comes to a mirrored climax when Sayid and Danielle point rifles at each other, each taking exactly the same position and stance as the other. Sayid says he doesn’t want to hurt her; she retorts that he already has, a reversal. When Sayid pulls the trigger, nothing happens, and Danielle notes that Robert didn’t notice when the firing pin had been removed either – this scene has happened before, in Danielle’s experience. Danielle says he was sick; Sayid claims he is not sick…

(…and meanwhile, back at camp, a second new character, named Sullivan, is sick, well, kind of – he’s got hives, but he’s a hypochondriac. “Sullivan,” by the way, means “little dark eye” in Irish, echoing the Eye imagery of the opening battery of episodes. So we’re introduced to two new Losties in this episode, in addition to discovering Rousseau. Also, notice how Sayid is tortured in the episode after he tortures someone. When he begs Rousseau to stop, we cut to a Flashback where the man he’s torturing begs for it to stop. Sayid says he doesn’t want to hurt Rousseau… and says just as much to Nadia in Iraq. Rousseau thinks that Sayid believes she’s insane… while Hurley complains that they’ll all “go crazy” without some fun. He’s impaled in his left leg right next to where he shot himself the last time he saw Nadia, a twinned wound. And, of course, there’s the mention of Whispers, followed by a scene where there are Whispers. Anyways.)

Danielle won’t let go of Sayid until he lets go – by saying what’s on the back of his picture of Nadia: “You’ll find me in the next life if not in this one.” The implication, of course, is that there’s a second reality, a second life to had, just on the other side of the looking glass.

Noor Abed-Jazeem

Noor Abed-Jazeem

Names are important in LOST, as we’ve seen with the invocation of John Locke and as we’ll see shortly with the invocations of Rousseau and Sayid. Before we get to them in the intermission, though, let’s take a look at Nadia, who occupies a rather interesting position in this story and who has a very interesting name – her birth name is Noor Abed-Jazeem. We’ll get to “Noor” in a second, but let’s start by going backwards. “Jazeem” means “resolute, determined, unshakeable,” while “Abed” means “worshipper.” So Nadia is an unshakeable worshipper, which is exactly how she’s presented — in the face of being tortured, she refuses to cave in. She will not divulge any information. Sayid puts her in solitary confinement, but this does not break her.

So it’s interesting that she prefers the name Nadia, a nickname meaning “delicate” in Arabic. However, there’s nothing delicate about this woman – she’s tough. She’s been burned with acid, the soles of her feet have been flayed, and the palms of her hands have been drilled into, leaving the marks of stigmata. Which is peculiar, given that Nadia is Muslim, for such stigmata are decidedly Christian, representing the wounds Christ received during his crucifixion. (And then there’s the fact that the first “stigmatic” was actually Saint Francis, in the 13th Century; the Tau Cross, basically a glorified T, is the cross of the Franciscan Order, and is the cross of the Hanged Man in the Waite-Smith tarot deck. Nadia, by the way, is called a “traitor” by Sayid.)

However, Nadia’s first name is Noor, or Nūr, a word with a very specific religious connotation in Islam. The 24th surat of the Quran, Sūrat an-Nūr, or “The Light,” contains the most esoteric verse of the text, a parable of the Divine Light:

Allah is the Light of the heavens and the earth.

The parable of His Light is as if there were a niche,

And within it a Lamp: The Lamp enclosed in Glass;

The glass as it were a brilliant star;

Lit from a Blessed Tree,

An Olive, neither of the East nor of the West,

Whose oil is nearly luminous, though fire scarce touched it;

Light upon Light!

Allah sets forth parables for men: and Allah knows all things.

So Nadia was actually named for this kind of light, for the light of Divinity. So while it may be surprising that Nadia also bears the marks of Christendom as well as partaking of Islam, this is only because of sectarian expectations. Hopefully the Light of the Universe transcends such categorization. Which, actually, the Light Verse points to. After all, it comes from a Blessed Tree, of neither West nor East – this sounds very much like the World Tree that transcends the pairs of opposites, and whose oil is luminous without the need for fire. It is, in other words, not a physical light so much as that light which is reflected from the mirror of the heart.

So perhaps we should consider the Western meaning of “Nadia” — rather than the Arabic meaning of “delicate,” let’s go with the Russian meaning of “hope.” Which is actually how Sayid describes his relationship to Nadia during his final confrontation with Rousseau:

SAYID: I know what it’s like to hold on to someone. I’ve been holding on for the past seven years to just a thought, a blind hope that somewhere she’s still alive. But the more I hold on, the more I pull away from those around me.

Of course, we should also point that Nadia’s role in Sayid’s story is a spiritual one, and she appears in every one of his FlashBacks. When she arrives, Sayid’s already an accomplished torturer. But she’s not afraid of him. She still sees in him the little boy she knew when she was growing up, a boy she was attracted to. She sees a divine light within his heart:

SAYID: This isn’t a game, Nadia.

NADIA: Yet, you keep playing it, Sayid — pretending to be something I know you’re not.

At this point we should note that when Sayid first talks about Nadia to Rousseau, he indicates that Nadia is dead, because of him. So when Nadia’s execution is ordered, and Sayid brings Nadia a black hood, it seems that we’re going to get a scene that shows us how Sayid brought about Nadia’s demise. However, this is only a pretense – he’s actually planned to save her.

SAYID: Forty meters outside this door there’s a supply truck that will be leaving shortly. They don’t check them on the way out, only coming in. Get inside. Cover yourself any way that you can. They won’t reach the city for thirty minutes; that’s enough time for you to jump out and hide yourself.

NADIA: Come with me.

SAYID: I can’t. Desertion. They would kill my family. I don’t have your courage.

NADIA: You have more than you know.

Again, Nadia seems to be able to see things inside Sayid that he can’t see himself. And then Sayid actually succeeds in saving her. She’s no longer dead within the narrative – it’s as if she’s been resurrected. And in so doing, it’s as if Sayid has been redeemed. He lets go of Nadia, ironically, when confronted by Rousseau, and in turn she lets him go.

Letting go, we must remind, is a precursor to Grace.

July 20, 2016 @ 9:07 am

Brilliant article again. Once completed I would buy a book of this interpretation of the show if made!

July 20, 2016 @ 2:17 pm

Great as usual, Jane. I can’t say it enough, but I really love these posts and look forward to each new one.