Lost Exegesis (The Moth) — Part 2

You can find Part 1 of the essay here. Usually, the essay is spoiler-free until we get to the “Looking Glass” portion after an intertextual intermission. In this case our selected cultural artifacts are all much more interesting in how they function prophetically, so here’s your advance notice of spoilers from here on out.

Intermission

Saint Jack

SAWYER: Ah, damn. Didn’t I tell you? Word from the valley is Saint Jack got himself buried in a cave-in.

Let’s start with Saint Jack, a movie directed by Peter Bogdanovich based on the novel by Paul Theroux. Now, Paul Theroux, we should point out, isn’t just a novelist, he’s also justly known as a great travel writer, thanks to his travels to Africa, Singapore, and Japan. He’s earned the enmity of several governments, largely for bringing to light certain aspects of their countries which they’d preferred to keep covered up.

That said, I think the movie is much more celebrated than the book, so that’s what we’ll be attending to. It was shot in several months entirely on location in Singapore, under the pretense of being a standard rom-com (“Jack of Hearts”) as opposed to an adaptation of Saint Jack. After it was released, the movie was banned in Singapore for decades. So it’s got that, at least, in common with the book.

(What is it about “covering” things up? Come to think of it, Jack covers for Charlie at the end of The Moth, lying that Charlie has the flu to make his withdrawal more socially acceptable.)

The film is possibly some of the best work by Bogdanovich and lead actor Ben Gazzara, who plays the titular Jack Flowers. Jack Flowers is an American expat living in Singapore in the 70s. He makes his living by running a brothel, which also supports his drinking. Jack makes it work because he does not judge the people in his life. It’s not like he’s in a position to without being a hypocrite, but then we see all kinds of hypocrites in Jack’s line of work. He doesn’t use force or intimidation or privilege to navigate the world – no, he looks at everyone as deserving of his attention and respect and warmth, and even when he’s proven wrong he does little more than walk away. So Jack is a “saint” in this rather spiritual respect, in how he manages his relationships, not in terms of his “sins.” He’s a saint, but he’s no saint.

The movie meanders for quite a while, basically a series of vignettes featuring Jack interacting with his clients, workers, and other people, but it’s got a couple of pivotal moments. The first is when the local mob takes down Jack’s place of business, wrecking his establishment and dispersing his people, while marking his arms with tattoos comprised of various epithets and obscenities. This is actually about the halfway point of the movie. Jack goes to another tattooist to put down more tattoos that effectively integrate the Asian hieroglyphs into pictures of flowers. This scene features a mirror hanging on the back wall, through which Jack is reflected.

Obviously not a scene that has much of anything to do with The Moth, but it’s certainly relevant to Jack’s backstory, which we find out in the deeply underrated episode Stranger in a Strange Land, which details how Jack got his tattoos – in Thailand (which is pretty damn close). It’s interesting, because Stranger in a Strange Land plays with many of the Saint Jack tropes – once Jack is marked, he is meant to become anethama in the eyes of the local culture. The tattoos are defining – for Jack Shepherd, his destiny, and for Jack Flowers, well, he’s the lotus in which a certain jewel can be found, shall we say. Certain scenes, like running through markets, are practically duplicated (not cinematically so much as thematically.)

So what we have here is a literary intertextual reference, “Saint Jack,” that foreshadows if not prophesies later evens in the text of LOST. This strongly implies that it’s valuable to follow up on these references, that they are not tangential to the text but deliberately evocative and meaningful to it.

The second main “plot point” of Saint Jack (it’s a relatively plotless film) comes at the end, when Jack is recruited by the military’s “pimp” in Singapore to photograph a certain liberal anti-military Democratic senator in flagrante with a male prostitute. The point being that the man’s homosexuality becomes a source not of pleasure but of pain, of judgment. Jack succeeds in getting the photographs, but then his integrity, based on his true morality, trumps his desire for a $25,000 payout and he flings the pictures into the river, granting him the freedom to return to his friendly life in Singapore’s underground. (And it really is an underground – this is what Singapore didn’t want to admit of itself, which is why the film was banned there for so long. All the relevant locations, by the way, have since been bulldozed.) In so doing, the film aligns itself with Jack’s morality, one based not on a provincial understanding of good and evil, but one rooted in empathy. It’s certainly a perspective shared by The Moth, which doesn’t castigate Charlie for his drug use, but for its function as a false substitute for his relationships with his brother Liam and his music.

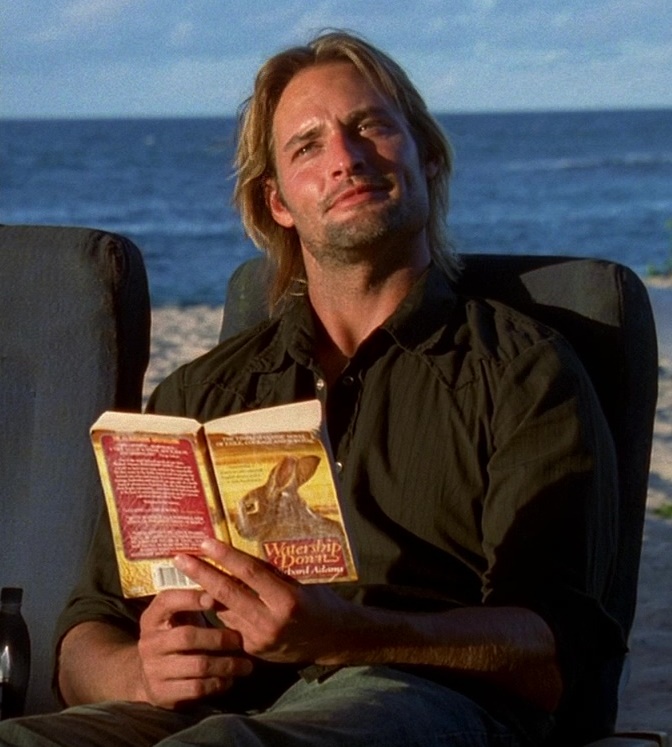

Watership Down (Part 3)

Part 3 of Watership Down is entirely concerned with the rabbits’ infiltration of a warren on the other side of their world to steal away females for breeding purposes, since a group of rabbits comprised entirely of boys will obviously have fertility issues. The plot is neatly split in two. On the one hand we have the leader Hazel, his brother Fiver, and several other rabbits preparing the escape route. On the other hand we have Bigwig entering Efrafa, pretending to be an eager office-wannabee, all by himself. He finds several females (does, in the parlance of rabbit) and engineers their escape from the overcrowded military-esque warren that’s run by General Woundwart. Our heroes are chased down, but escape on a small boat in a nearby river.

Again, this doesn’t really have anything to do with The Moth.

We could point out that there’s a kinship between the trickery of rabbits and the clever bit with Sawyer in this episode. Namely, how Sawyer, by withholding the information about Jack’s imperilment, attempts to deflect Kate’s pity. But we’ll be getting Watership Down again in the next episode, when it becomes clear that Sawyer has more in common with tricksy rabbits than we’d known.

So instead we’ll take this opportunity to once again demonstrate the prophetic nature of LOST’s literary references. I’m speaking, of course, of the next major subplot that’s just around the corner: the infiltration of the Losties by someone who lives on the other side of the Island. This stranger pretends to be a survivor, but he’s actually a resident, and his purpose is to steal away the pregnant woman of the group, because the Island apparently has fertility issues. Significantly, this plot development shares the “chiastic” structure of, say, Liam and Charlie trading places over the course of The Moth, in that positions of the protagonists and antagonists have been reversed – rather than rooting for the infiltrators like in Watership Down, we’re now rooted in the experiences of the group that’s been infiltrated.

Given that we have established a relationship between the literary elements of LOST’s intertextual references and the show itself, let’s turn to the very interesting mythological “Story of El-ahrairah and the Black Rabbit of Inlé” in the middle of Watership Down’s third part. In this tale, El-ahrairah basically journeys to the land of Death in an effort to save his besieged people. He offers his life, but the Black Rabbit refuses it. He wagers away his ears and tail in contests in which the Black Rabbit easily prevails. He even tries to infect himself with plague, to smite his enemies in self-sacrifice, but even here he is outwitted. Finally, El-alhrairah gives up:

Then at last El-ahrairah felt that his strength and courage were gone. He fell to the ground. He tried to move, but his back legs dragged along the rock and he could not get up. He scuffled and then lay still in the silence.

“El-ahrairah,” said the Black Rabbit at least, “this is a cold warren: a bad place for the living and no place at all for warm hearts and brave spirits. You are nuisance to me. Go home. I myself will save your people. Do not have the impertinence to ask me when. There is no time here. They are already saved.”

It is this moment of “letting go” that Grace comes, a boon bestowed for no earthly reason, and certainly not because it has been earned or anything like that. El-ahrairah is an abject failure, and yet his people are still saved. Obviously, we’ll be looking out for thematic resonance along this line in future episodes. We’ll also be looking out for things like “there is no time here,” and El-ahrairah’s being “forgotten” by his people when he finally returns.

The Phantom Tollbooth

The Phantom Tollbooth

KATE: What we’re doing… chasing some phantom distress signal… what are the odds of this working?

SAYID: No worse than the odds of us surviving that plane crash.

KATE: People survive plane crashes all the time.

SAYID: Not like this one. The tail section broke off when we were still in the air. Our section cart-wheeled through the jungle and yet we escaped with nothing but a few scrapes. How do you explain that?

KATE: Blind dumb luck?

SAYID: No one’s that lucky. We shouldn’t have survived.

KATE: Sorry Sayid, some things just happen, no rhyme, no reason.

Finally, we turn to one of my favorite childhood books, The Phantom Tollbooth. This is an utterly delightful and whimsical turn into an Other World, as the bored little boy Milo enters the Lands Beyond and becomes a hero. See, the Lands Beyond are in need of healing because the twin princesses, Sweet Rhyme and Pure Reason, have been taken away to the Castle in the Air. In other words, there’s no Rhyme and no Reason in this other world. Based on the dialogue above, that was enough “rhyme and reason” to include this book in the Exegesis. But what sealed the deal for me was Charlie’s line with Jack in the Caves:

CHARLIE: This place, it reminds me of confession, those little claustrophobic booths.

Not to mention the fact that The Awful Dynne, a monster made of smoke in The Phantom Tollbooth, seems like a pretty good nod to the Smoke Monster of the Island, which, naturally, makes an awful din when it appears. Indeed, both monsters seem to be in the habit of collecting interesting sounds.

Now, I’m aware that this is a likely apocryphal intertextual reference. It’s not like The Phantom Tollbooth actually appeared in the show, like Watership Down, nor was it directly referenced in dialogue, like Saint Jack. It’s something we had to dig for, an excavation that necessarily required foreknowledge of the reference itself in order to be found. This is not an unusual literary technique. T.S. Eliot’s epic poem The Waste Land, for example, is rife with allusions to other unspecified works, works which add texture and connotation to the poem – works that facilitate the act of interpretation. It is in this spirit that I view LOST, which at this point has already presented its bona fides when it comes to intertextual relevance. So with that in mind, let’s take a look at The Phantom Tollbooth and see if it says anything interesting about The Island, or even just the underlying premise of being lost.

The first thing to note about The Phantom Tollbooth is the aesthetic in which it partakes. It’s very much a deliberate work of children’s literature, insofar as it delivers a message regarding the value of becoming educated, but it’s very much in the vein of the Faery-Story. You pass through a magic portal to a Special place, where the “rules” of reality are based in a different logic. Fantastic adventures ensure. This is the logic of Narnia, for example, and passing through a magic wardrobe is very much like passing through a magic tollbooth.

Or perhaps the logic of Alice in Wonderland would be more apt (passing through a looking glass, it’s all the same). For the people and places of The Phantom Tollbooth are beholden to a very sophisticated and yet very simple play on the nature of language, specifically on the fact that so many words carry multiple meanings in so many different ways, thanks to the magic of idiom. The “weather man,” for example, becomes “the Whether Man,” and plays his role as such. A “watch dog,” on the other hand, ends up literally having the torso of an alarm clock. In a place where you literally eat your words, it’s best to have a short speech reciting your favorite menu prepared. This impetus to demonstrate the absurdity of literalism informs the entire book.

For example, at one point our heroes (Milo, the boy; his watch dog, Tock; and the Humbug, who is just that) start getting cocky and jumping to conclusions about how easy their road will be – and sure enough, they literally jump to an Island called Conclusions, where they have to work out how to escape. Hmm… an Island. Anyways, the first thing that Milo says about this is perhaps a perfect indicator that someone is “lost”:

For example, at one point our heroes (Milo, the boy; his watch dog, Tock; and the Humbug, who is just that) start getting cocky and jumping to conclusions about how easy their road will be – and sure enough, they literally jump to an Island called Conclusions, where they have to work out how to escape. Hmm… an Island. Anyways, the first thing that Milo says about this is perhaps a perfect indicator that someone is “lost”:

“Pardon me,” said Milo to the first man who happened by, “can you tell me where I am?”

“Pardon me,” replied the man, “can you tell me who I am?”

The strange man proceeds to describe himself in pairs of opposites – he’s tall as can be, and as short as can be; as generous as can be, and as selfish as can be; as strong as can be, and as weak as can be; and so on. Once our heroes ascertain the man’s identity (Canby, of course), they learn how to escape their predicament.

I bring all this up as a metaphor for LOST. Because LOST is just as much, if not more, about the mysteries of being human as it is about the mysteries of the Island. And at this point, there seems to be a correlation between Island mysteries and character mysteries. There’s a moth on the Island, and Charlie ends up ritually embodying that experience – the metaphor becomes strangely literal. At this point, the cave skeletons “Adam and Eve” are more important for understanding Kate’s psychology than for answering questions about the show’s mythology. And there’s certainly a lot of word play when it comes to LOST – from all of Sawyer’s nicknames to the way the show repeats certain phrases and words to create thematic resonance (like Jack’s constant invocation of “fix,” or people talking about “the others” before The Others even become known, let alone a plot point). And hell, before the end of this season we’ll even be mining the show for numbers.

“Whether or not you find your own way, you’re bound to find some way. If you happen to find my way, please return it, as it was lost years ago.”

Finally, there are several actual references to being “lost” in The Phantom Tollbooth. Perhaps they can illuminate some of the deeper mysteries of LOST. First up, a quote from The Whether Man. It works as a pun, and yet it’s pithy. The Whether Man has lost his way. He’s so concerned with accommodating every kind of reality (whether this or that) that he literally can’t make his mind up about everything. He ends up standing under a solitary cloud that rains only over him. Which is what can happen to us when we fail to be who we are, and refuse to make any choices in our lives.

“I think I’m lost. Can you help me please?”

“Don’t say ‘think,’ ” said one sitting on his shoe, for the one on his shoulder had fallen asleep. “It’s against the law.”

Here, Milo is lost in the Doldrums. Which is actually another way of being metaphorically lost in your life. And it’s actually rather related to the Whether Man’s sense of being lost. Except rather than being bewitched by all the possibilities, Milo is instead too dull to consider any possibility. It’s still the same, though – an inability to choose a way forward. As it turns out, to escape the Doldrums simply requires “thinking” – thinking about anything. The way out of being lost, here, is to turn within.

“I think we’re lost,” panted the Humbug, collapsing into a large berrybush.

“Nonsense!” shouted Alec from the high branch on which he sat.

“Do you know where we are?” asked Milo.

“Certainly,” he replied, “we’re right here on this very spot. Besides, being lost is never a matter of not knowing where you are; it’s a matter of not knowing where you aren’t—and I don’t care at all about where I’m not.”

Here we get an “extended” lecture on the nature of being lost, from a boy named Alec who grows down rather than up, and will only be an adult when his feet finally reach the ground. Anyways, it’s a rather simply philosophy – to avoid being lost, one only need Be Here Now. But the converse that Alec presents is also interesting: not knowing where you aren’t. Now, I know I’m not at the opera right now, so in this sense I’m not lost. But what if I don’t know that where I am now actually is an opera, and I’m just misinterpreting it? Then maybe I am lost, because I don’t know I’m not not at the opera.

In terms of the Island, though, let’s take a look at some popular theories and how they fit in with this understanding of being LOST. One theory is that they’re all Purgatory, or some place you go to when you’ve died. They’re not in any of those places, but they don’t know that, and at various points in the show they come to realize they don’t quite know that they’re not in those places. For example, Locke’s father Anthony Cooper believes he’s in hell, just before Sawyer strangles him. Cooper doesn’t know where he’s not. That’s why he’s lost, which certainly contributes to his subsequent death.

Which is to say that being lost is really a matter of perspective, which is emphasized in another passage that also takes place in The Forest of Sight:

“Do you want to ruin everything? You see, to tall men I’m a midget, and to short men I’m a giant; to the skinny ones I’m a fat man, and to the fat ones I’m a thin man. That way I can hold four jobs at once. As you can see, though, I’m neither tall nor short nor fat nor thin. In fact, I’m quite ordinary, but there are so many ordinary men that no one asks their opinion about anything. Now what is your question?”

“Are we lost?” asked Milo once again.

“H-h-m-m-m,” said the man, scratching his head. “I haven’t had such a difficult question in as long as I can remember. Would you mind repeating it? It’s slipped my mind.”

Milo asked the question for the fifth time.

“My, my,” the man mumbled. “I know one thing for certain; it’s much harder to tell whether you are lost than whether you were lost, for, on many occasions, where you’re going is exactly where you are. On the other hand, you often find that where you’ve been is not at all where you should have gone, and, since it’s much more difficult to find your way back from someplace you’ve never left, I suggest you go there immediately and then decide. If you have any more questions, please ask the giant.”

Even I get lost in that kind of logic. And yet there’s something tantalizing about this, when we take into account the nature of the Flashbacks, and the recurring phrase “go back” that permeates the show. First, to understand that you were lost is actually rooted in the nature of reflection, of actively examining your memories. If we understand the Flashbacks as being experienced as Memories in addition to being a narrative device, we can see how Charlie’s understanding of how he was lost in his life before the plane crash helps him to make different choices going forward, indeed informing him of where he wants to go and who he wants to be be.

Secondly, the Thin Fat Short Giant makes an interesting point that once you’ve realized you’ve made a mistake (you’ve been somewhere you shouldn’t have been) it behooves you to go back to that point to work your way forward, rather than trying to go back to the place you believe you should have been but never actually visited. In other words, don’t pretend to be who you’re not. Which is actually the objection that Milo made about this fellow.

“You did a fine job,” he said, patting Milo on the head. “Someday I’ll let you conduct the orchestra yourself.”

Tock wagged his tail proudly, but Milo didn’t say a word, and to this day no one knows of the lost week but the few people who happened to be awake at 5:23 on that very strange morning.

This is a fun one. In the Lands Beyond, it takes a symphony orchestra to paint the world in color. Milo, completely enchanted by the “music,” tries to orchestrate the moment before dawn… and at 5:23am, he orchestrated a hyper-accelerated week-long psychedelic event. (Sounds more like The Grateful Dead to me.) This is what’s called “lost,” this adventurous step into another reality.

At the same time, let’s note that the idea that “sounds” would manifest as colors, a form of synesthesia, is taken to its logical conclusion in the Valley of Sound, where a bass drum beat manifests as a giant cotton ball, and a round of applause appears as a stream of paper sheets fluttering to the ground. At this point in the story, Milo is learning the lesson of false dichotomy — that’s it’s perfectly possible for presumably contradictory or separate things to in fact mingle. (The terms of set logic are actually rather inadequate for capturing the human experience.) This, in turn, helps him to defeat the Mathemagician in a logical dialectic, gaining consent and assistance to advance to the Mountains of Ignorance.

Neither the Mathemagician nor his brother Azaz, the King of Dictionopolis, will agree with the other as a matter of principal. Milo fuses this opposition together by noting that they both agree to the same “rules” of their conflict. This permits Milo to rescue Sweet Rhyme and Pure Reason. Now, it’s interesting that both come across as “higher” functions of Words and Math. They embody the union of opposites, in that they’re twins, and as such recognize the inherent value of holding both positions. They never compete, but always complement. And this is what heals the world. (There’s also a nifty conversation on the value of making mistakes.)

Finally, the last meaning of “lost” from The Phantom Tollbooth (emphasis mine):

“In a few minutes they’d reached the crest, only to find that beyond it lay another one even higher, and beyond that several more, whose tops were lost in the swirling darkness. For a short stretch the path became broad and flat, and just ahead, leaning comfortably against a dead tree, stood a very elegant-looking gentleman. He was beautifully dressed in a dark suit with a well-pressed shirt and tie. His shoes were polished, his nails were clean, his hat was well brushed, and a white handkerchief adorned his breast pocket. But his expression was somewhat blank. In fact, it was completely blank, for he had neither eyes, nose, nor mouth.”

So, the tops of the Mountains of Ignorance in a swirling darkness – in other words, ignorance veiled in ignorance. A most unfavorable epistemological state of being to inhabit. But I’m just as interested in the monster that our heroes confront here – a man with no discernible identity who turns people into laborers. Laborers who receive no compensation save for a good feeling. The faceless monster of capitalism? Alas, no, the Terrible Trivium is simply a monster of habit, wasted effort – of worthless, petty tasks.

The meta joke, sadly, is that the show will never deliver in a straightforward expository fashion the actual nature of the Island and the storytelling of it. When it comes to the story of the Island, LOST is but a tip of the iceberg: most of the mysteries reside under the sea.

Anyone who explored The Phantom Tollbooth, Saint Jack, or Watership Down at this early stage in the game for LOST would be particularly well-equipped to appreciate certain developments in the show as it progressed.

Through the Looking Glass (The Moth)

Wordplay

If The Phantom Tollbooth represents the sort of thing we can find through a little bit of digging, perhaps we can apply its lessons to the show at large, or at least this episode. For this is an episode that plays quite a bit with words. In the first part of the essay, we noted how “rock god” was a repeated phrase that took on new meanings given a new context – rather than just ostensibly referring to Charlie’s musicianship, it became a phrase of  foreboding, immediate preceding two cave-ins. And then there’s its redemption, when Hurley tells Charlie “You rock!” after he saves Jack.

foreboding, immediate preceding two cave-ins. And then there’s its redemption, when Hurley tells Charlie “You rock!” after he saves Jack.

MICHAEL: Alright, this area here is load-bearing. We’ve got to dig where there’s no danger of the wall buckling in on itself. Here, we dig in here so the wall doesn’t collapse. Four at a time, by hand, until we can find some kind of shovel. We take shifts, and go slow. Whoever isn’t digging should be clearing the rocks that we clear out and bring the water to whoever is working.

KATE: Why is nobody digging?

MICHAEL: We’ve got enough people to dig. You keep going at this pace you’re going to kill yourself.

Perhaps the most repeated non-trivial word in The Moth is “dig,” and it’s used in several different contexts. Most obviously, digging through the cave-in. Yet even here there’s a nifty little joke – when Michael tells Kate she’s going to kill herself “going at this pace,” it behooves us to remember that Charlie’s last name is Pace. So while on the surface Kate is going after Jack, there’s also an implication that she’s going after Charlie, which is relevant as an inside joke, as Evangeline Lilly and Dominic Monaghan were dating at the time.

LOCKE: You see this little hole? This moth’s just about to emerge. It’s in there right now, struggling, it’s digging its way through the thick hide of the cocoon. Now, I could help it, take my knife, gently widen the opening, and the moth would be free. But it would be too weak to survive. The struggle is nature’s way of strengthening it.

It’s the use of “digging” that helps to link Locke’s metaphor of The Moth to Charlie’s activities around the cave. Charlie will dig through a little hole, albeit one in the earth, and emerge as someone who’s been transformed. And now we can see the Caves as a sort of cocoon as well, a place where the act of self-transformation can occur in general.

SAWYER: Heard the doctor was vacating the premises. Thought I’d best lay claims to my new digs before somebody else did.

SAWYER: So, he’s a doctor, right? Yeah, the ladies dig the doctors. Hell, give me a couple of band aids, a bottle of peroxide, I could run this Island too.

And then we get Sawyer’s quips. Two different jokes that use “dig” in unexpected ways. Both, interesting, have something to do with Jack, referring to Jack’s previous “home” on the beach and the notion that Kate is fixated on Jack because he’s a doctor. In both cases, though, notice how Sawyer is inserting himself into Jack’s place, both in the literal sense of taking over Jack’s digs, and imagining himself as the Island’s leader if he only had some medical credentials.

We’ll return to this recurring theme of “replacement” in a bit, but while we’re on the subject of Sawyer’s magnificent use of language, let’s consider his latest nickname for Sayid: “Mohammed.” Mohammed was the creator of Islam, the principal religion of the Middle East, where Sayid hails from. Mohammed’s inspirations and prophecies came during his long stays in a cave (naturally) where he had retreated from his dissatisfying life in Mecca. At the age of 40, he proselytized his new religion until his death nearly 23 years later, converting most of the Middle East.

We’ll return to this recurring theme of “replacement” in a bit, but while we’re on the subject of Sawyer’s magnificent use of language, let’s consider his latest nickname for Sayid: “Mohammed.” Mohammed was the creator of Islam, the principal religion of the Middle East, where Sayid hails from. Mohammed’s inspirations and prophecies came during his long stays in a cave (naturally) where he had retreated from his dissatisfying life in Mecca. At the age of 40, he proselytized his new religion until his death nearly 23 years later, converting most of the Middle East.

One of the principal rituals of Islam is known as Salat, where five times a day the dedicant supplicates himself to Allah. The prayers and prostrations are performed facing the city of Mecca, wherein lies the Kaaba, a large cube-like building surrounded by a mosque. The eastern corner of the Kaaba is the Rukn-al-Aswad, likely a meteorite known also as the Black Stone – its very blackness is said to be due to all the sins of the ages that it has absorbed.

Let’s not forget our translation of the Frenchwoman’s distress call. In it, she says they have to go to “the black rock.” Sayid, a Muslim, is in essence looking for a “source” which transmits a message about a “black rock.” It’s not the same Black Rock, of course, but that’s not what matters here. This is the kind of wordplay that the show deals in – creating threads of thematic resonance.

JACK: Call me a broken record, but caves are a natural shelter, and a hell of a lot safer than living here on the beach.

SAYID: Our section cartwheeled through the jungle and yet we escaped with nothing but a few scrapes.

JACK: The signal has been running on a loop for 16 years, Kate.

KATE: You don’t want off this Island because there’s nothing for you to go back for.

I want to highlight some of the other interesting language that’s crept into this episode, and indeed the entire series. It kind of goes back to the metaphor implied by the Frenchwoman’s transmission – a signal that’s been running a loop for sixteen years, and yet every iteration that we heard in Pilot Part 2 is slightly different. The implication is one of circularity, but a circle that changes, that isn’t entirely static. Perhaps it’s a way of suggesting evolution.

But there’s also an important phrase to consider in light of this juxtaposition: DriveShaft, the name of Charlie’s band. A “driveshaft” is basically a long thin cylinder that’s used to transmit rotational power across a distance, and usually depends on “universal joints” to connect the various components of a drive train. Implicit, then, in the name of Charlie’s band is the concept of rotation, of circularity. But this is also coupled by the basic “schema” of a driveshaft, namely that it functions as an axis. As we’ve pointed out before, the axis mundi – as represented by the World Tree, for example – is the “center” which connects Above and Below, Past and Future, to the Here and Now. So there’s also the principle of connectivity implicit in the name of Charlie’s band.

Finally, we might want to take a look at the lyrics of their hit song: “You all everybody / You all everybody / Acting like you’re stupid people / Wearing expensive clothes / You all everybody / You all, everybody.“

The lyrics are, admittedly, insipid, purportedly stolen from the outburst of an audience member at The Phil Donahue Show. But there’s still a couple of interesting aspects to consider here. First, the song is certainly inclusive, drawing a connection to “everybody.” Second, though, is the implication that is made about everybody – acting like we’re stupid people wearing expensive clothes. Which basically accuses us all of pretending to be dumber than we are, while simultaneously covering up that deceit through artificial materialism. To find the true self, then, requires digging through several layers of cover-ups. This will become much more relevant in our exploration of the next episode.

The Aesthetic of Mirror-Twinning

The Aesthetic of Mirror-Twinning

So, it’s finally time to cover the interesting shots and anomalies in The Moth. As everything preceding would suggest, there’s plenty of material that qualifies for LOST’s mirror-twin aesthetic. Luckily I don’t need thousands of words to demonstrate the aesthetic, as it’s plain to see from the scene in the dressing room where Charlie and Liam have their big fight, and Charlie ends up making a horrible decision. Just about every shot here incorporates a mirror. We get shots of Charlie literally twinned by two mirrors, taking up multiple reflections. Both he and Liam share similar poses in front of the mirror. The cinematography of director Jack Bender is just phenomenal. And it’s not like it’s a gratuituous stylistic flourish — this is literally what happens to Charlie and Liam — they are mirror-twinned in their trajetories, as one goes from straight-laced to junkie while the other goes from junkie to straight-laced. If anything, the show is hitting us over the head with the aesthetic here.

LOST, though, is also an examination of identity, and I find it interesting that the two characters yield very different reactions. I mean, the both have periods of lucidity, and periods of addiction. Does the actual order of these presentation actually matter when it comes to discerning their identities? LOST would seem to argue that the order very much matters. It matters, because we don’t exist in eternity. What happened, happened, but what actually matters is the here and now. It doesn’t matter if you used before, or if you were clean back when, it only matters where you are here and now. The present is really the only thing relevant. Charlie and Liam may be mirror-twinned, but one went first, and the other followed.

We can “pull back the camera,” as it were, and look at the “gaps” in the story. Obviously Liam wasn’t always a junkie. At some point in his life, he started using. And then, eventually, he stopped. And now we see Charlie going through the exact same thing. He wasn’t always a junkie. But at some point in his life, he started using. And eventually, he stopped. Filling in all the gaps, both Liam and Charlie have experienced the same journey, like congruent but out-of-phase sine waves. We’ve just been shown the story in a more dichotomous way.

The other thing of particular note in The Moth is a matter of continuity. Now, LOST is actually really quite superb when it comes to “continuity.” For example, Sayid gives Kate a watch in this episode, to help her synchronize the fireworks and the antennaes that will triangulate the Frenchwoman’s transmission. We’ve noted the importance of watches before, in just the last episode, in fact. In this scene, there are several cuts as the camera circles around the group of Sayid, Kate, and Boone, and the match-cuts of Kate donning the watch are impeccable. Impeccable! And in all the various scenes, which were surely not shot in story-order, the watch is appropriately worn (or not) by Kate. This is a demonstration that the people in production are on their game.

Which makes a particular scene with Charlie and Liam stand out like a sore thumb. Charlie and Liam are walking through some cloisters, with Liam to Charlie’s right. Liam holds the record contract in his right hand. Two nuns cross their path, and Liam looks at them strangely. In the next shot, we see Liam and Charlie exiting the cloisters and walking onto the grass. But now Liam is on Charlie’s left, and holding the record contract in his left hand. It’s in this scene that Liam gets Charlie to change his mind about sticking with the band. This is the moment when they start trading places, and here we have a continuity error where they literally take each other’s places relative to each other.

I think this is significant, especially in light of Fire+Water, the Season 2 episode which features Liam “escaping” through some “prison bars” (in actuality the oversized crib or cot for the diaper commerical they’re filming). We’ve talked about the alchemical meaning of one person taking another’s place — it’s the principal of Equivalent Exchange. In a “fate machine” situation it doesn’t matter who, exactly, is taking the preordained fate, just so long as the fate is confirmed and acted out. But it can matter, depending on the situations that then befall the person who ends up in the clutches of Fate.

For example, what if you got to The Looking Glass station, and realized that you didn’t know how to key in Good Vibrations? You’re sure it’s the right thing to do, you just don’t know how to do it. But your brother… who’s practically a mirror-twin of you, he would know. He would remember. He could key in Good Vibrations, because he’s a real musician. And, as it turns out, it’s vitally important that Good Vibrations gets keyed in. Maybe, you believe, the fate of the world depends on it. Or the fate of people you’ve come to love. The fate of a baby. If you could go back, and get your brother to take your place, and all it took was tricking a security system into thinking you were basically one and the same, wouldn’t you be obliged to do so? Or, less charitably, wouldn’t you be tempted to let someone else drown in your place?

March 2, 2016 @ 1:31 am

I’m fuzzy on the details of the Looking Glass Station bit — been years since I watched — but that last paragraph is a hell of a thought.

March 2, 2016 @ 4:57 am

I missed a beat on that — should have added, “rather than face the music?”

🙂

March 30, 2016 @ 7:29 am

Loving these articles, I’ve watched the whole 6 series through 3 times but reading this again makes me think it’s time for a slower revisit!

April 27, 2016 @ 7:37 am

Hi Jane,

Loving this series of articles! Any idea when the next one (Confidence Man) will be available? Hope you’re ok.