Lost Exegesis (Solitary) — Part 2

In the first part of our Exegesis of Solitary, we explored the mirror-twinning of Sayid and Danielle, the meaning of do-overs or “mulligans” in golf, and the principle that “names are important” when it comes to decoding LOST in our discussion of Nadia. We now enter the second part of theses essays, an Intermission where we dive deep into the intertextuality of the show.

In the first part of our Exegesis of Solitary, we explored the mirror-twinning of Sayid and Danielle, the meaning of do-overs or “mulligans” in golf, and the principle that “names are important” when it comes to decoding LOST in our discussion of Nadia. We now enter the second part of theses essays, an Intermission where we dive deep into the intertextuality of the show.

Intermission

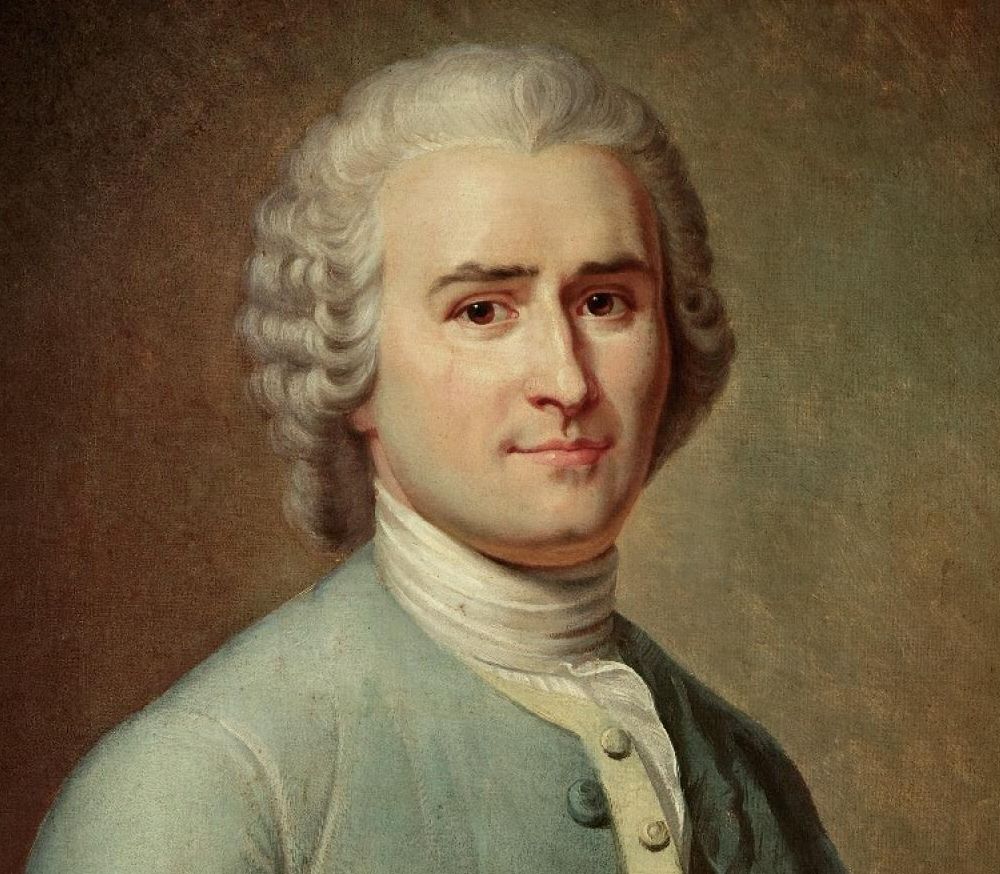

Jean-Jacques Rousseau

With the introduction of Danielle Rousseau, we get our second invocation (after John Locke) to another Enlightenment-era philosopher. Jean-Jacques Rousseau (1712 – 1778) was born in Geneva, Switzerland, and his mother died nine days later due to complications from the childbirth. His personal life was, frankly, a mess. With his semi-literate seamstress, Thérèse Levasseur, he sired five children, all of whom were deposited at a foundling hospital soon after birth, which Rousseau later regretted. His early writings on music were published in an early Encyclopedia, and he even invented a new system of musical notation based on numbers, but those works were never considered very important. He alienated every colleague he ever worked with, from Diderot to Hume, and his antagonistic writings against religion forced him to flee arrest in both France and Geneva. Later in life he became paranoid with delusions of plots conspired against him, as detailed in his Reveries of a Solitary Walker. He died a recluse, but by no means a hermit, as he still held his wife and a few friends dear.

Rousseau’s writings had a tremendous impact on Western culture. To him the idea of the “noble savage” is usually attributed; Rousseau imagined that man in his “natural state” – before society – was naturally good, in that such a self-sufficient man was not subject to the vices of politics and government. As such, things like his Discourse on Inequality have relevance to our Losties, stranded in the middle of nowhere and essentially forced to create a society all on their own. Indeed, the text of LOST seems to confirm Rousseau’s rebuttal of Hobbes’s contention that in the state of nature, with no civilization, all was “continual fear and danger of violent death; and the life of man, solitary, poor, nasty, brutish, and short”:

“There is another principle which has escaped Hobbes; which, having been bestowed on mankind, to moderate, on certain occasions, the impetuosity of egoism, or, before its birth, the desire of self-preservation, tempers the ardour with which he pursues his own welfare, by an innate repugnance at seeing a fellow-creature suffer. I think I need not fear contradiction in holding man to be possessed of the only natural virtue, which could not be denied him by the most violent detractor of human virtue. I am speaking of compassion…”

Our Losties have not been at each others’ throats since returning to a state of nature. Indeed, they’re pulled together remarkably well to live together (so as to avoid dying alone), despite the fact they’ve hived off into two camps at the Beach and at the Caves.

However, I’m not so sure that Rousseau’s conclusions have been fully verified, either. According to Rousseau, by joining together through the “social contract” individuals can both preserve themselves and remain free – through submission to the authority of the general will of the people, all authors of “law”, in essence guaranteeing against being subordinated to the wills of others. But neither has this been the case. While Jack plays the part of ostensible leader, not everyone obeys him (again, half the people didn’t follow him to the Caves) and there’s no one playing the part of Leader at the Beach. Furthermore, there are opportunities for other people to create new social structure of their own initiative, as Hurley has with the opening of his golf course.

Rousseau, by the way, was also a novelist as well as a philosopher. Like most philosophers, his fiction is wedded to philosophical discourse, and in Julie, or the New Heloise, we get a story told in the form of letters written between two lovers which explore the conflict between the dictates of society (even those morals presumably reached through the mechanics of “reason”), and the “secret principles” of one’s inner identity. Julie loves St. Preux, and he loves her, but due to their different social standings they cannot marry; Julie ends up with the aristocrat Wolmar instead. She does her best to suppress her longings, but in the end confesses that her passion truly belongs to St. Preux… and then she conveniently dies in an act of self-sacrifice to save her child. As Julia puts it in her last letter:

“Long have I indulged myself in the salutary delusion, that my passion was extinguished; the delusion is now vanished, when it can be no longer useful. You imagined me cured of my love; I thought so too. Let us thank heaven that the deception hath lasted as long as could be of service to us. In vain, alas! I endeavored to stifle that passion which inspired me with life; it was impossible; it was interwoven with my heart-strings. It now expands itself, when it is no longer to be dreaded; it supports me now my strength fails me; it cheers my soul even in death.”

She goes on to say that the combination of their passion and virtue will unite them forever in the “mansions of the blessed,” implying reunion in their deserved afterlife. Overall, then, I am reminded of the relationship between Sayid and Nadia. Sayid’s passion for Nadia is true, but it is Nadia who is resolute in bringing forth their authentic selves – she will not betray her virtue. This does not mean, however, a life lived without subterfuge: Sayid plays the con man, faking Nadia’s escape and murder of the captain, which he accomplishes himself. But he too is possessed by virtue – he cannot escape with her on account of needed to protect his family back home.

So it goes.

Perhaps it would also be constructive to examine Rousseau’s final writings, his Reveries of a Solitary Walker, a title that practically screams out for us to consider both Danielle and Sayid in its light. Indeed, the very word “reverie” acquired a positive connotation upon Rousseau’s usage of it, having previously been considered as a kind of anxiety or a “ridiculous” flight of imagination. And yet, there are passages within that are rather dark, ruminating on the imminence of death:

“But despite this desuetude of my body, my soul is still active; it still produces feelings and thoughts; and its internal and moral life seems to have grown even more with the death of every earthly and temporal interest. My body is no longer anything to me but an encumbrance, an obstacle, and I disengage myself from it beforehand as much as I can.”

“Only with difficulty does my soul any longer thrust itself out of its decrepit wrapping; and were it not that I am hopeful of reaching the state to which I aspire because I feel I have a right to it, I would no longer exist but by memories.”

“Experience always instructs, I admit; but it is profitable only for the time we have left to live. Is the moment when we have to die the time to learn how we should have lived?”

These passages are striking. Rousseau considers the willful disengagement from his body as death approaches, identifying himself more with his memories than anything else, and wonders if this is the time to actually profit from one’s regrets, or at least to learn from that final judgment. Sadly, such speculation does not seem to provide any insight into this episode. Yes, Sayid seems to bear regret for his past actions not to mention his lost love, and Danielle is surely sad in her loneliness, but neither seem particularly on the verge of death. I mean, it’s not like anyone got shot or anything.

Nonetheless, we shall bear these sentiments in mind going forward. Not everything in LOST bears fruit immediately—some of its mysteries may well take time to pay off.

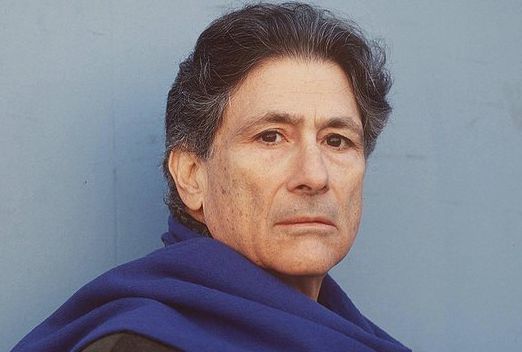

Edward Said

Edward Said

SAYID: Who were the carriers?

DANIELLE: The others.

SAYID: What others?

I know the spelling of Sayid’s first name and Edward Said’s last name are different. However, they are homophones, and besides, there’s plenty of material within the text of LOST to suggest that Said’s work on cultural imperialism and the “othering” of people is influential. So, Edward Said was a Palestinian-American literary theorist and outspoken activist best known for his 1978 book Orientalism, wherein he writes of how Western writings on the Orient (that is, the Middle East and parts of Asia) are suspect and cannot be taken at face value, due to the history of European colonial rule and political domination in that area. By depicting the Orient an irrational, weak, feminized “Other”, contrasted with the rational, strong, masculine West, a contrast he suggests derives from the need to create “difference” between West and East that can be attributed to immutable “essences” in the Oriental make-up.

“This is not to say that Orientalism unilaterally determines what can be said about the Orient, but that it is the whole network of interests inevitably brought to bear on (and therefore always involved in) any occasion when that peculiar entity ‘the Orient’ is in question. How this happens is what this book tries to demonstrate. It also tries to show that European culture gained in strength and identity by setting itself off against the Orient as a sort of surrogate and even underground self.”

The idea that the colonial powers “othered” the East in order to subjugate them is only part of the general philosophy of “othering.” Hegel was one of the first to express the idea that “the other” is in fact defines or constitutes “the self.” In sensing the separateness between the Self and Other, feelings of alienation are created, and one’s perspective of the world necessarily changes. Other is the necessary complement to Self, which fits in nicely with the themes we’ve seen running through Lost.

We’ve already seen some reference to “the other” in the text of Lost, though it may have gone unnoticed until now. In the Pilot episode, Jin speaks with Sun: “You must not leave my sight. You must follow me wherever I go. Do you understand? Don’t worry about the others. We need to stay together.” As Jin and Sun seem “other” to us and the rest of the castaways due to race and more importantly language, so too are we “other” to them.

Jack’s process of separation from the group he’s come to lead is reflected in White Rabbit, when he speaks with Locke: “How are they, the others?” Sayid, for that matter, when speaking to Jack alone in Tabula Rasa about the effect of the dying Marshal’s groans, refers their fellow passengers similarly: “The others are getting upset.”

In Pilot Part 2, when Sayid first picks up the Frenchwoman’s transmission (a deduction made because he’s picked up “feedback,” implying a loop), Boone wonders if there are “other survivors” on the Island. According to Shannon’s translation, Danielle is saying, “I’m alone now, on… on the island alone. Please someone come. The others, they’re… they’re dead. It killed them. It killed them all.” In Tabula Rasa, while sitting around a campfire, Sawyer calls this transmission “that other thing,” and Kate reiterates to Jack that the message said “the others were dead—something had killed them all.” So we’ve already known that “others” have been on this Island, which Danielle once again confirms, referring to them as those who “whisper.”

“It is hegemony, or rather the result of cultural hegemony at work, that gives Orientalism the durability and the strength I have been speaking about so far. Orientalism is never far from what Denys Hay has called the idea of Europe, a collective notion identifying ‘us’ Europeans as against all ‘those’ non-Europeans, and indeed it can be argued that the major component in European culture is precisely what made that culture hegemonic both in and outside Europe: the idea of European identity as a superior one in comparison with all the non-European peoples and cultures.”

More poignantly, LOST seems to be addressing both Said’s point about Orientalism as well as the underlying premise of the “us-versus-them” mentality in general. First, there’s been a fair amount of subversion (at least in 2004, when this season began) when it comes to certain storytelling tropes about people from the Middle East and Asia. For example, we’re initially presented with Jin and Sun as a couple with a stereotypical marriage – Jin as domineering and Sun as submissive – which is subsequently upended when we see how their relationship formed. And now we get into Sayid’s backstory, with a strong woman helping him to recognize how much he abhors the work he’s been doing and to find the inner strength to stop. Yes, both stories are essentially love stories, but the love story is, at least in Western culture, a universalized story, something used to find common connection with other people (indeed, that would seem to be a significant principle of love itself)—and this in turn is paired with as much a focus on the interiority of Sayid, Sun, and Jin as we’ve gotten from the other white characters. I would argue that this is a powerful tonic. The text teaches us to care for these characters as much as anyone else.

I find it especially interesting that in Sayid’s backstory, our characters have a variety of motives that are not typically ascribed to the conflicts in Iraq. We don’t know yet why Sayid got into the business of torture, but he’s primarily motivated by his relationships (to Nadia and to his family) than to any political or religious ideology. Likewise, Nadia’s comments on what The Republican Guard have done to her body indicates an antipathy towards how the Ba’athist regime wielded and abused their power. Their motives are personal and idealistic, not ideological. Conversely, we get Danielle Rousseau – a European – placed in the role of the “noble savage,” someone who is just as adept at using torture (and failing to get any valuable intel), as well as someone who could justifiably be described as not being right in the head. She is wild and untamed, and yet almost childlike at the same time, a strong reversal of how Europeans are typically depicted—and at the same time ironic in the sense that she is partaking of tropes usually assigned to “the other.”

Dr. Quinn, Bizet’s Carmen, and Simone de Beauvoir

Dr. Quinn, Bizet’s Carmen, and Simone de Beauvoir

JACK: You want it easy, quit moaning. I’ve got to change these bandages.

SAWYER: Well, try not taking my skin off with them. How’d I score the house call, Dr. Quinn? Trying to ease your conscience?

Let’s start with Dr. Quinn, Medicine Woman, which is a direct reference thanks to Sawyer’s nickname of Jack at the beginning of the episode. Sawyer, of course, is trying to needle Jack by misgendering him, which we’ll get back to in a little bit. In the meantime, let’s actually consider the TV show in question. Dr. Quinn ran on CBS in the mid-to-late 90s, and later in syndication for, like, ever, starring Jane Seymour as the eponymous Dr. Michaela “Mike” Quinn, a Boston doctor who relocated to Colorado in the “Old American West” of 1867. So, it’s in the genre of a Western.

Except it isn’t. This was definitely a feminist show, and an intersectional one at that. It wasn’t about lauding toxic masculinity typically perpetuated by the Western genre, but rather about granting dignity and power to those disenfranchised by that hegemony. Dr. Quinn proved over and over again that her gender was irrelevant to her ability to practice medicine, except in how she had to prove herself over and over again to the people around her. The series covered a number of other social issues, including racial prejudice and homophobia, not to mention single parenting, adoption, coming of age, family dysfunction, mastectomy, and so forth. It was not a particularly critically praised show at the time – it certainly wasn’t subtle in its political messaging, for example, and garnered Emmy wins only for its technical achievements, though Seymour was nominated several times.

However, we can see in Dr. Quinn an influence on the series of LOST. Mind you, LOST is much more serialized than Dr. Quinn, which basically relied on the romance between Quinn and mountain man Byron Sully as far as long-term plot developments are concerned (Quinn and Sully married at the end of Season Three). That said, all of the characters were rooted in their own backstories, which were slowly revealed over the seasons. And like Dr Quinn, we’ve had no shortage of “issue” stories on LOST, with themes of euthanasia, racism, torture, drug addiction, Iraq, and daddy issues right out of the gate, not mention allusions to building a new society “in nature” through its evocations of certain so-called Enlightenment philosophers.

KATE: This thing have a ladies team?

JACK: Hey, when did you show up?

KATE: A while ago. I almost didn’t recognize you. You’re smiling.

Sawyer calling Jack “Dr Quinn” isn’t the only gender play in this episode. Just the fact that Danielle is named after the famous Jean-Jacques Rousseau, falling in line after the reveal of John Locke, is rather interesting, especially in context with the song that plays from her music box: the intermezzo of Bizet’s opera Carmen, which back in 1875, France, the Carmen was somewhat controversial, given its depiction of passionate immorality and tragic lawlessness.

Carmen, a fiery gypsy working at the smoky cigarette factory, represents untameable passion, seducing the naïve soldier José into freeing her after she’s captured by Zuniga, the officer of the guard, for attacking another woman with a knife. José and Carmen end up embroiled in a plot by smugglers, which leads to José deserting his post. A “card reading” foretells Carmen’s death, and in the meantime a bullfighter named Escamillo successfully woos Carmen. José kills her during the bullfight when she mocks and scorns him.

So, obviously, there are some feminist readings to glean from this. Gotta love Carmen for wanting to do her own thing, not being tied to any man. Gotta be displeased by how much the men in the story want to tie her down, and especially José, who can’t accept her rejection. It sucks that he’s treated as a tragic character, as someone whose hubris earns her death, though by no means does the text seem to judge her – indeed, as the main character, the opera positively revels in her. Consider how Carmen (her name is a shade of red) is juxtaposed with the bullfighter at the end, but one who ends up being gored by the bull rather than winning the bout. She’s wild, and willful, and very much her own woman, which is something to admire all on its own, she’s just been done in by an animal in the end.

I’m very much tempted to compare this story to JJ Rousseau’s story of Julie. In Carmen, we also see people who are moved by their own passions, and who try to authentically follow their bliss. But whereas in Julie the characters’ tragedy is rooted in following the dictates and duties of society, in Carmen they are undone by not following said dictates and duties. It seems you just can’t win!

Aside from that, there are (again) parallels to consider with regards to Solitary. Sayid, of course, is the soldier convinced to reject his military duties, much like José, though at least Sayid is smart about doing so in a way that doesn’t implicate himself. Does this make Nadia our Carmen, the passionate woman who does what she needs to do out of her own authenticity? Or is Rousseau our Carmen, with her wildness and freedom, matching wits with a man who would kill her? Rousseau, thankfully, isn’t killed, and neither is Nadia, apparently – both women are strong, sympathetic, and free.

“If we do not love life on our own account and through others, it is futile to seek to justify it in any way…”

– Simone de Beauvoir, The Ethics of Ambiguity

Simone de Beauvoir is not directly or indirectly invoked by the text of LOST. Nonetheless, she haunts this episode, with its insistence of exploring the dynamics of “othering” and presenting us with a woman who invokes a French philosopher in Danielle Rousseau. So let’s have a French female philosopher who has actually written about the Other and who indeed precedes Edward Said on this account. For de Beauvoir, much like Said, the Other is constructed by those in power to set up certain dualities by which an imbalance of power can be maintained, except here it’s the othering of woman by men, within the province of Western society itself. This is ultimately a trap, though – for the construction of the Other is always a part of the construction of the Self, at least in the Hegelian sense. The Other is always a mirror, and we must always recognizes that there’s another consciousness there, just as there is here. Which is why freedom is not an individual project, but a social one, and a political one. If anyone isn’t free, then no one is really free.

So let’s take a look at this in regards to Solitary. First, we have to consider Sayid’s imprisonment at the hands of Rousseau, juxtaposed with how he imprisons Nadia in FlashBack. By de Beauvoir’s theory, neither Sayid nor Rousseau are truly free while they play the captor to someone else. Sayid’s very being, for example, is reduced to that of the “communications officer” who gets people to communicate through the practice of torture; in reducing other people to objects, he himself is reduced to a caricature. But when he finally frees Nadia, he also frees himself to be the person he truly is within. Likewise for Rousseau – she gets nowhere trying to find out about Alex through electrocuting Sayid, and even when he’s fixing her music box, he’s still chained to the desk, and so too is she chained to a past which she can’t let go of. Only when Sayid convinces her of the value of letting go, both of him and her obsessions, is she free to become an independent agent once again.

Wagner’s Ring Cycle

Wagner’s Ring Cycle

Finally, I want to touch on an Apocryphal intertextual reference, namely Wagner’s epic opera, Der Ring des Nibelungen. The Ring Cycle as it’s commonly known tells the story of a magic ring desired by Wotan (another name for Odin), a ring that grants dominion over the entire world, but which he has to give to the giant Fafner to save all the gods. Wotan’s daughter Brunhilde gets involved in the plot, intervening to save Sieglinde, the mother of Siegfried, who is destined to kill Fafner, and for this Wotan puts her in a deep sleep encircled by fire. Siegfried comes of age, kills Fafner (who has become a dragon), and acquires the ring. After waking Brunhilde from her slumber, they pledge to bring down the gods, and through treachery and revenge and redemptive sacrifice they succeed. This story, in turn, became a source for Tolkein’s The Lord of the Rings. (I wonder if that reference will emerge any time soon.)

This really doesn’t sound like the small opera of LOST at all, true. As I said, though, this an apocryphal reference, not directly alluded to in the text, but through some striking details that obliquely point to it. First, we should note, is the nature of their respective scores. Both rely heavily on leitmotifs – repeated musical signatures denoting character, action, themes, and so on – and it’s Wagner’s Ring Cycle that first used leitmotifs in a systematic fashion. In LOST, we have different themes for all of our characters, as well as various themes for certain emotional moods (even the act of climbing) that recur throughout the text.

One of the musical compositions of the Ring Cycle is called “Forest Murmurs,” a moment when Siegfried gains understanding of birdsong and the animal kingdom itself after tasting Fafner’s dragon blood. Which, I dunno, evokes to me the scene of Sayid running through the jungle and hearing whispers, which confers to him an understanding of Danielle’s metaphorical song. This understanding happens at dusk… and the last chapter of the Ring Cycle is called “Twilight of the Gods.” At this point Sayid is limping through the forest with a walking stick, not unlike that which Wotan wields, but Wotan’s is inscribed with words. (It would be cool if something like that appeared in the show.)

The second act of the Ring Cycle takes place in a home within which a massive Ash Tree grows. Remember, in Norse Mythology, the Ash Tree is a signifier of the World Tree, Yggdrasil, the central axis mundi which connects Above and Below, Past and Future, to the Here and Now. So I find it particularly striking that Danielle’s home, burrowed into the earth, has a Banyan tree in its center. The Banyan Tree serves as an equivalent symbol in many mythologies of the South Pacific, where the Island is presumably located, given that Danielle says they were three days out of Fiji when her team shipwrecked on the Island. Interestingly, the main island of the Fiji archipelago, Viti, was first visited by European sailors who shipwrecked on the island.

Finally, the end to the Ring Cycle was rewritten several times by Wagner – at first the gods weren’t destroyed, then they were; at one point the gods are redeemed, and later are admonished; in one version, it’s declared that Love has replaced the gods as ruling the world; in another, a vaguely Buddhist ethos of “letting go” of the endless cycle of rebirth is emphasized. It seems, in other words, that Wagner got several Mulligans on this.

Through the Looking Glass (Solitary)

Through the Looking Glass (Solitary)

If you really don’t want to be spoiled regarding future episodes of LOST, let alone the conclusions of the Exegesis, you really should stop now, as the “Through the Looking Glass” portion of these essays takes into consideration the future events of the series with regard to the present episode in question.

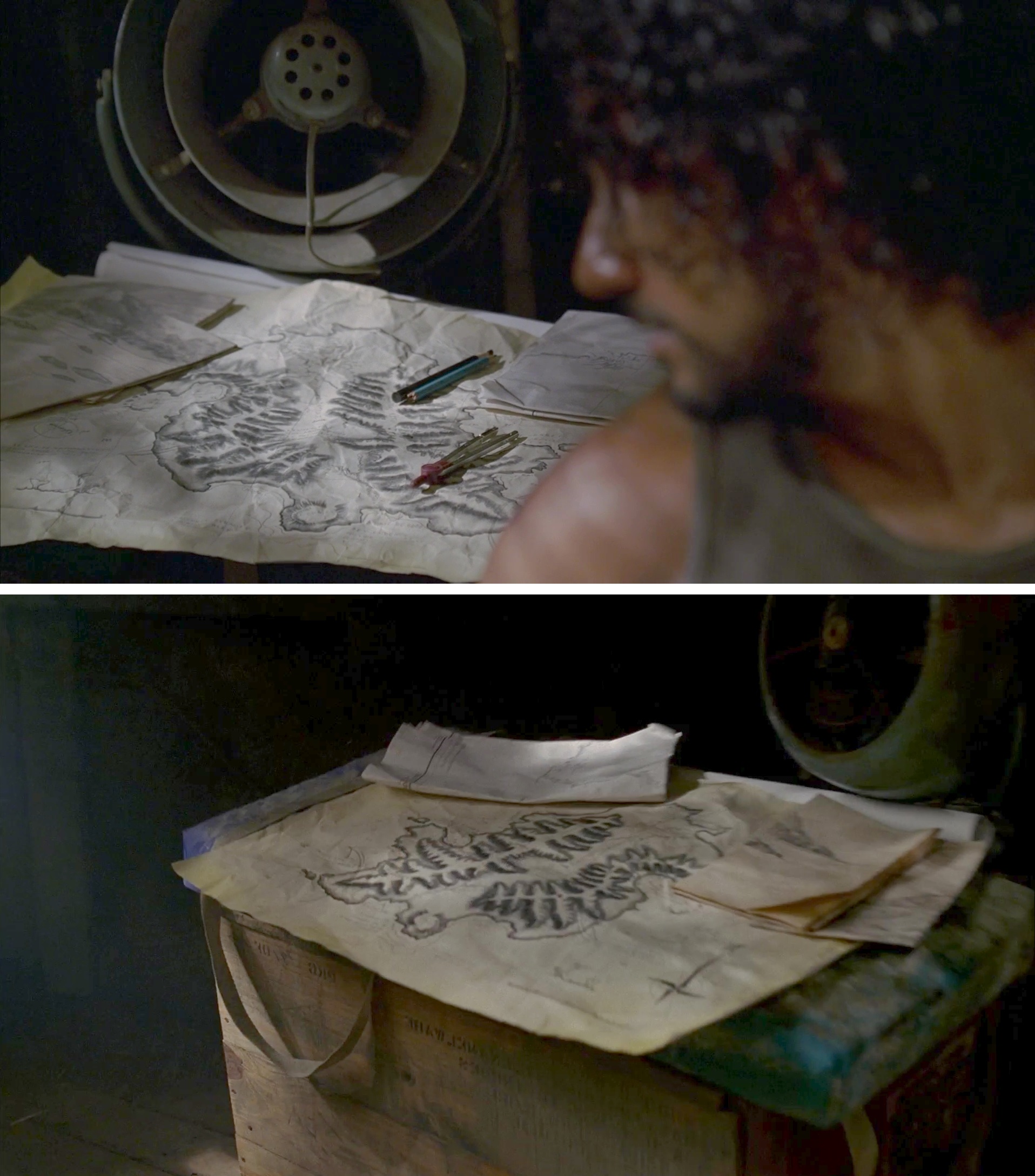

Now that you have informed consent, let’s begin. In previous essays we’ve obsessed about “continuity” and about mirrors, specifically with how the show seems to present “reversed images” at crucial moments insofar as our characters’ choices are concerned. We get quite the doozy of a convergence in this respect when Sayid decides to take Danielle’s maps. So, consider the two images here. In the first, while Sayid is working on Danielle’s music box (which has three mirrors on it) he looks over his shoulder and sees the maps of the Island that she’s made sitting on the table. In terms of how the shot is framed, we see a folded up map in the upper right hand corner that’s aligned with the orientation of the map. In the upper left hand corner, there’s a pair of maps, one of which is positioned diagonally with respect to the larger map.

Now, when we get to the shot later in the episode of Sayid taking the map, we see again a diagonally placed map in the upper left hand corner, and in the upper right hand corner the folded up maps are aligned with the larger map’s orientation; they are parallel/perpendicular. However, this is in fact a reversed image. Look carefully at the picture of the Island on the main map – the “tail” of the Island curves to the right of the frame, while in the second picture it curves to the left, and when Sayid eventually enters the frame, we see his watch on his right wrist instead of his left.

I believe this reversed image to be deliberately constructed, because the orientations of the smaller stacked maps on the larger map should also be reversed with respect to the framing of the shot. But they aren’t! Which means the props were rearranged so that a reversed image would maintain continuity with the earlier shot that is not reversed.

Furthermore, the reversed shot is twinned in the scene – after we see Sayid take the maps, we get a non-reversed shot of him folding up more papers, and then a second reversed shot of him stuffing his bounty into his backpack.

Finally, the scene ends with an alchemical principle. As Sayid climbs out of the dugout, the camera pans down to the pictures of Nadia which Sayid has left behind. So, Sayid has taken one set of documents and left behind another set. This is called “equivalent exchange,” for in alchemy there must always be respect for balance, which is part of the process of the “union of opposites.” We saw something similar in The Moth, when the Caves are alternatively described (twice) in terms of “cool” and “warm.”

Finally, the scene ends with an alchemical principle. As Sayid climbs out of the dugout, the camera pans down to the pictures of Nadia which Sayid has left behind. So, Sayid has taken one set of documents and left behind another set. This is called “equivalent exchange,” for in alchemy there must always be respect for balance, which is part of the process of the “union of opposites.” We saw something similar in The Moth, when the Caves are alternatively described (twice) in terms of “cool” and “warm.”

We are considering if mirror-shots are re-entry points for characters going back to change the past, to make a different choice, and in so doing erasing what previously happened. Taking a mulligan, as it were. But to do so, balance must still be maintained; a principle of duality or mirror-twinning prevails. If this is the case, this makes Sayid’s actions here much more self-conscious than they appear. But from what point in the future is he going back? The sub? The temple? I’m not sure at this point. What we do know, though, is that the maps will have two very important entailments for the “Rube Goldberg” cascade of events of Season One. First, they are at the origin of Sayid’s relationship with Shannon. Second, they will propel Hurley towards Danielle Rousseau. While Sayid likely doesn’t have much insight into Hurley’s relationship with the Numbers, he’d certainly be motivated to go back and initiate his relationship with Shannon as early as possible.

Other Mirrorings

Before we get into a discussion of what it means to go back, there are a few other mirrorings to attend to. First, of course, is the matter of the cable Sayid finds on the beach. We now know that this cable leading out to sea (into the water, a reflective surface) goes to The Looking Glass, which has as its logo a rabbit, tying right back into all the bunny references we’ve had so far. So the Looking Glass, the mirror, is a kind of a rabbit hole, a tunnel, a way to access what might be termed The Other Side.

I find it particularly interesting that what Sayid actually sees when he finds the cable is a part of it that’s become unsheathed. The metal inside isn’t copper, but silvery in appearance. Silver, of course, is traditionally what’s used on the back of a sheet of glass to turn it into a proper mirror. But there’s another image to consider her, which is simply The Silver Cord. In various strands of metaphysics, such as astral projection and out-of-body experiences, the Silver Cord is what connects the physical body to the astral body. In such experiences, it’s important that the cord isn’t stretched so far that it becomes broken – or else the traveler will become lost. Which, you know, is a euphemism for being dead. Notice, by the way, that the cord is buried in the earth, and Sayid has to lift it up, almost like a resurrection.

I find it particularly interesting that what Sayid actually sees when he finds the cable is a part of it that’s become unsheathed. The metal inside isn’t copper, but silvery in appearance. Silver, of course, is traditionally what’s used on the back of a sheet of glass to turn it into a proper mirror. But there’s another image to consider her, which is simply The Silver Cord. In various strands of metaphysics, such as astral projection and out-of-body experiences, the Silver Cord is what connects the physical body to the astral body. In such experiences, it’s important that the cord isn’t stretched so far that it becomes broken – or else the traveler will become lost. Which, you know, is a euphemism for being dead. Notice, by the way, that the cord is buried in the earth, and Sayid has to lift it up, almost like a resurrection.

This particular image appears in Ecclesiastes 12:

6 Or ever the silver cord be loosed, or the golden bowl be broken, or the pitcher be broken at the fountain, or the wheel broken at the cistern.

7 Then shall the dust return to the earth as it was: and the spirit shall return unto God who gave it.

In the Masonic interpretation, the Golden Bowl represents the brain, and the Silver Cord represents the spine. Jack Shephard is a spinal surgeon, who described all those nerves as “angel hair pasta” in Pilot Part 1.

Another mirroring worth considering vis-à-vis future events is the twinning of Sayid’s leg injury. He gets stake in the thigh, right next to where he shot himself in his FlashBack. This is actually something we’ll see again. John Locke, for example, will lose his kidney (or will have lost his kidney) and then ends up getting shot in the exact same place, which ultimately allows him to live. But more striking is the matter of Jack. In The End, he gets knifed in the gut, and we another similar wound right next to this. Which, of course, we learned about in Something Nice Back Home, when he has his appendix removed — during which he insists on employing a mirror so he can observe the surgery. Interestingly, by having his appendix removed, it can’t be burst when he later gets knifed there.

Finally, let’s return to the premise of alchemical exchange, with regard to Sayid and Rousseau. We’ve noted in the previous essay that they are heavily mirror-twinned, sharing dialogue and metaphor and even bodily positions. Most importantly, however, is how their drama plays out in terms of their character development. Rousseau’s working over of Sayid – and in particular, her opening of his envelope – is what leads him to start letting go of Nadia, so he can get back to the people with whom he needs to continue relationships with. In return, Sayid fixes her music box, which helps her to let go of Robert, and which will propel her into a new set of relationships. There’s a balance here. Each has given and received.

Bring Out Your Dead

DANIELLE: But Nadia, you left her, too?

SAYID: She wasn’t on the plane. She’s dead — because of me.

DANIELLE: I’m so sorry. I want to show you something.

“I want to show you something.” This is actually a repeated phrase in LOST, indicating something that’s actually quite important, like a central metaphor or concept. In The Moth, it’s the scene where Locke literally shows Charlie the moth in its cocoon, likening it to Charlie himself. Boone uses it in Further Instructions as part of Locke’s vision quest. In Happily Ever After, well…

DESMOND: Why’d you try and to kill me?

CHARLIE: I didn’t try and kill you. I was trying to show you something.

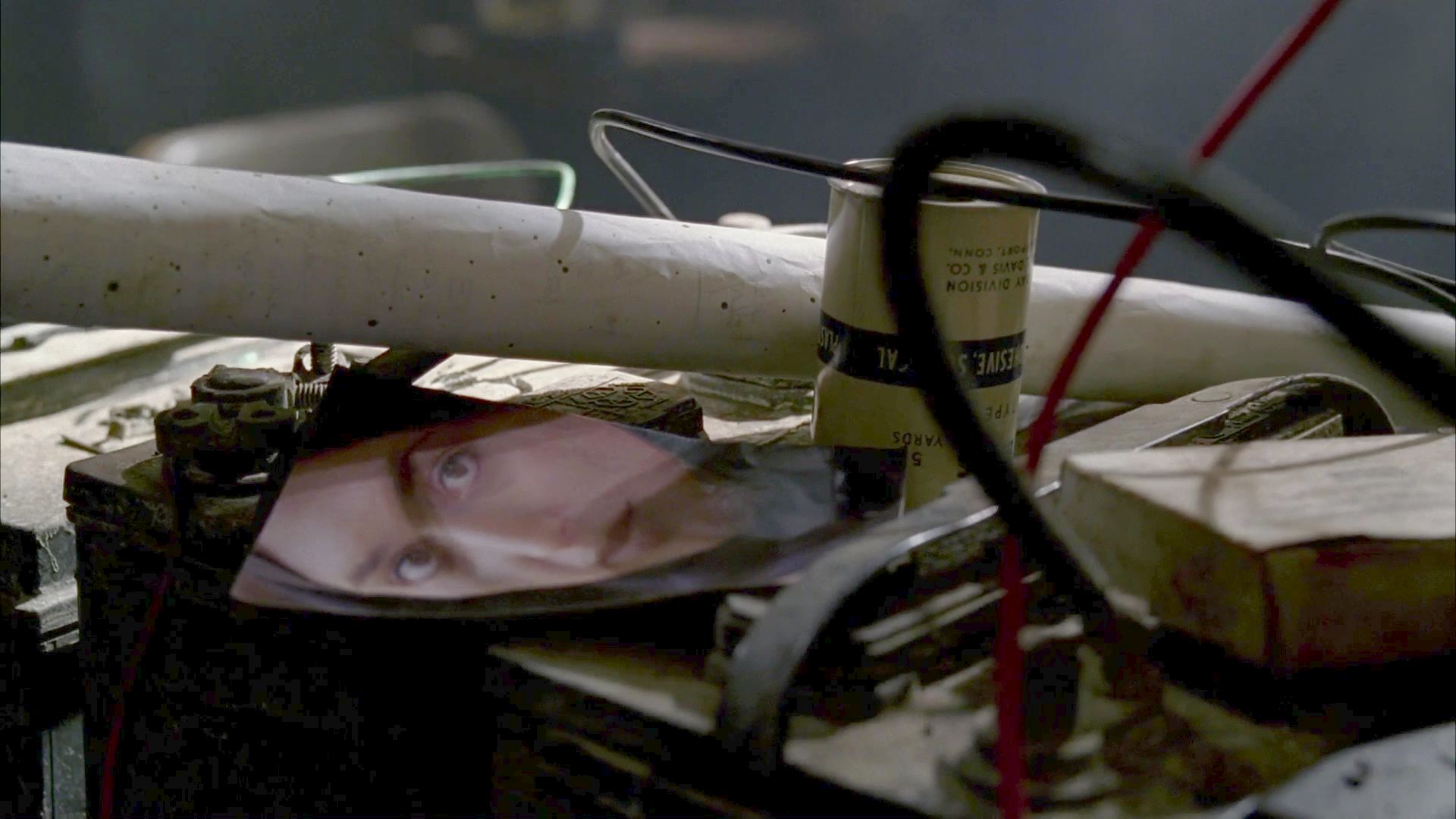

Trying to show him something indeed. What Danielle is trying to show Sayid, by the way, is her music box, which stands as a central metaphor in the episode. But what if she’s trying to show him something else? Something in the way that Charlie is trying to show Desmond? Reconsider that shot of Danielle and Sayid facing off:

Sayid pulls the trigger, but the rifle doesn’t fire. However, if Danielle is aware of the Island’s secrets, it wouldn’t matter. If the rifle fired, Danielle could just go back and remove the firing pin, which is what I think she actually did, hence the strong mirroring in that scene. In return, she “drugs” Sayid, really putting him into a state of unconsciousness that probably triggered his FlashBacks. FlashBacks in which, because of his own regret (this show is ultimately a collection of character studies, after all), he ends up saving Nadia after all. This, then, would explain why in one scene he seems to believe Nadia is dead, and in another scene recognizes that she might still be alive.

Sayid pulls the trigger, but the rifle doesn’t fire. However, if Danielle is aware of the Island’s secrets, it wouldn’t matter. If the rifle fired, Danielle could just go back and remove the firing pin, which is what I think she actually did, hence the strong mirroring in that scene. In return, she “drugs” Sayid, really putting him into a state of unconsciousness that probably triggered his FlashBacks. FlashBacks in which, because of his own regret (this show is ultimately a collection of character studies, after all), he ends up saving Nadia after all. This, then, would explain why in one scene he seems to believe Nadia is dead, and in another scene recognizes that she might still be alive.

I find it very interesting that Danielle’s music box is at the heart of this exchange:

SAYID: Danielle, please let me go.

DANIELLE: Go?

(The music box dies.)

SAYID: Back to the people I told you about.

The music box dies in the middle of the phrase “go back.” Because that is kind of what it takes to “go back,” to unhinge one’s consciousness from the physical body and travel back to another time period. This, I believe, is the ultimate secret of the Island, and why those who live here are so… effective at getting what they want, and often seemingly unafraid of dying. No wonder, then, Danielle’s retort to Sayid’s request is that “it’s not safe.”

The Whispers Are Beautiful

Finally, then, let’s talk about the Whispers. We’ll be going over their instances throughout the Exegesis at this point. According to the showrunners, the idea behind the Whispers changed over time, but I’m not really sure I believe them, for they’ve been very unreliable narrators, which is actually the perfect approach as an author for maintaining the secrecy of a text that’s actually oriented around faith.

So, briefly, here’s what we know about the Whispers. First, they’re not terribly audible. Most of the time we can tell when there is Whispering going on, but it’s rare for the words of the Whispers to actually be discernible (such as in Outlaws, when we hear “It’ll come back around,” which is a terribly apt phrase all things considered.) However, very clever people with computers and sophisticated sound equipment have isolated the Whispers and posted their transcripts of what they’re actually saying – for they are all composed of actual voices, albeit heavily processed. (They’ve also found Whispers hidden in audio tracks from other episodes, even in Pilot Part 1, but which aren’t audible at all in ordinary playback.) As it turns out, what the Whispers actually say is rather complicated.

In Solitary, for example, one listener (named Adawhen, apparently, who was an active member of ABC’s LOST forums back in the day) transcribed the Whispers as such:

Man: Just let him get out of here

Man: He’s seen too much already

Man: What if he tells

Woman: Could just speak to him

Man: No

According to David Fury, they were originally supposed to be The Others. Which, fine, but that doesn’t mean they aren’t dead, too, as Hurley determines in Season Six (as Juliet says at some point, they all learned a “dead language.” Regardless, the conversation is fascinating – particularly the idea that Sayid has “seen too much already,” now that Danielle has “shown” him “something” nice from back home.

Mind you, if these are dead people, why are they whispering at this point? We can’t say for sure, but what we do know is that the Whispering stops Sayid dead in his tracks. Which is what we also see happen to Sawyer in Outlaws, not to mention Shannon in Abandoned. (Ironically, Ben tells Rousseau to run if she ever hears them.) It’s the Whisperers who keep our Losties from blowing up the plane of Flight 316, which they all would have deeply regretted. Maybe, then, the intention of the Whispers in Solitary is alter Sayid’s fate, to get him to make some kind of course correction. Or, of course, it could all just be ironic. After all, one of the Whispers suggests speaking to Sayid, while another disagrees – all while Sayid has become aware that he’s hearing voices. Now isn’t that an interesting mirror?

Mind you, if these are dead people, why are they whispering at this point? We can’t say for sure, but what we do know is that the Whispering stops Sayid dead in his tracks. Which is what we also see happen to Sawyer in Outlaws, not to mention Shannon in Abandoned. (Ironically, Ben tells Rousseau to run if she ever hears them.) It’s the Whisperers who keep our Losties from blowing up the plane of Flight 316, which they all would have deeply regretted. Maybe, then, the intention of the Whispers in Solitary is alter Sayid’s fate, to get him to make some kind of course correction. Or, of course, it could all just be ironic. After all, one of the Whispers suggests speaking to Sayid, while another disagrees – all while Sayid has become aware that he’s hearing voices. Now isn’t that an interesting mirror?

July 26, 2016 @ 9:36 pm

Marvellous! Your “going back” theory is beginning to NEARLY convince me.

Also, this is almost just in time for a big anniversary: the complete version of Wagner’s Ring cycle was performed in Bayreuth for the first time 140 years ago this August.

There are no coincidences.

July 27, 2016 @ 1:53 am

Gee, thank you! All I really want to do is just show you something, so I’m glad you’re getting into it. 😉

August 3, 2016 @ 7:30 pm

You are, indeed, showing me something new, even after all the years I spent going back and back into this show. I never picked up on the repetition of “show you something” before, so thanks for giving me another motif to track.

November 16, 2016 @ 2:35 pm

Can’t wait until the next article… is this still in the pipeline? I check your blog every day waiting for it… 🙂

December 12, 2019 @ 6:10 am

If you do not want to get the low grades for your essay, you must write high-quality content. In this case, you can hire the editing services that will review your content.

December 26, 2021 @ 8:54 pm

this was a ride – does it continue anywhere else? I mean, there is enough so we all could continue on our own, but this was such a beautiful guide it sure is hard to just let go now