Lost Exegesis (Solitary) — Part 2

In the first part of our Exegesis of Solitary, we explored the mirror-twinning of Sayid and Danielle, the meaning of do-overs or “mulligans” in golf, and the principle that “names are important” when it comes to decoding LOST in our discussion of Nadia. We now enter the second part of theses essays, an Intermission where we dive deep into the intertextuality of the show.

In the first part of our Exegesis of Solitary, we explored the mirror-twinning of Sayid and Danielle, the meaning of do-overs or “mulligans” in golf, and the principle that “names are important” when it comes to decoding LOST in our discussion of Nadia. We now enter the second part of theses essays, an Intermission where we dive deep into the intertextuality of the show.

Intermission

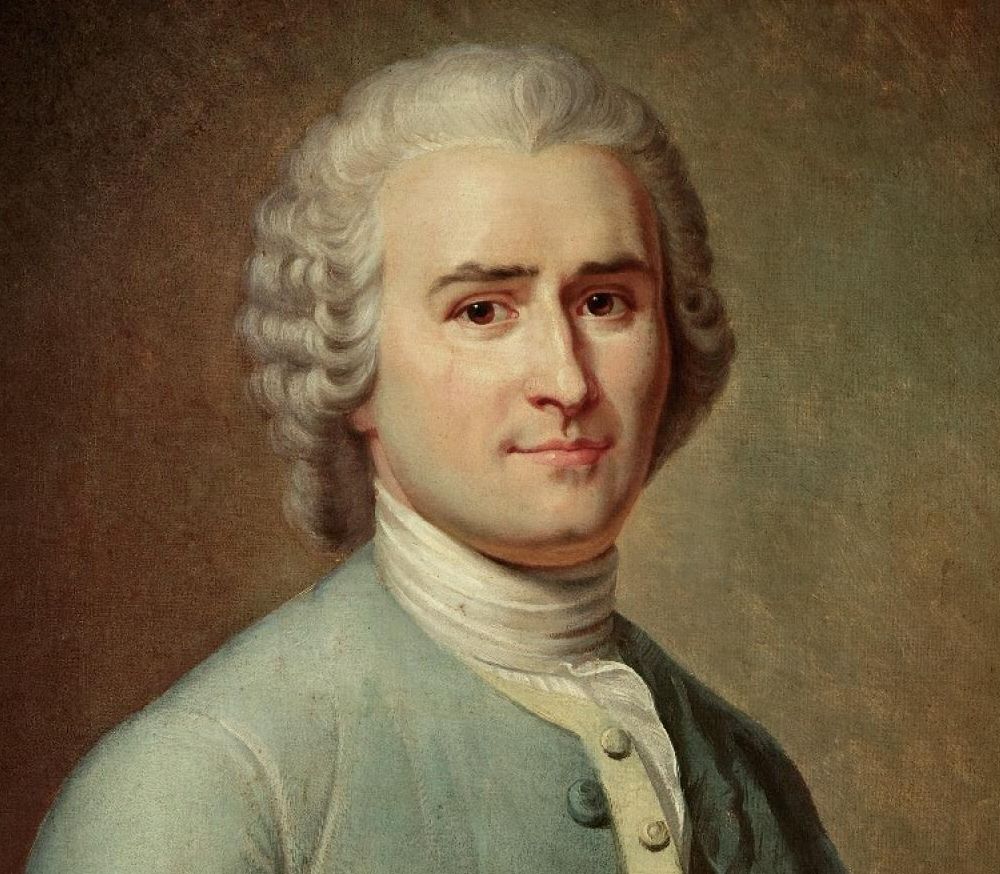

Jean-Jacques Rousseau

With the introduction of Danielle Rousseau, we get our second invocation (after John Locke) to another Enlightenment-era philosopher. Jean-Jacques Rousseau (1712 – 1778) was born in Geneva, Switzerland, and his mother died nine days later due to complications from the childbirth. His personal life was, frankly, a mess. With his semi-literate seamstress, Thérèse Levasseur, he sired five children, all of whom were deposited at a foundling hospital soon after birth, which Rousseau later regretted. His early writings on music were published in an early Encyclopedia, and he even invented a new system of musical notation based on numbers, but those works were never considered very important. He alienated every colleague he ever worked with, from Diderot to Hume, and his antagonistic writings against religion forced him to flee arrest in both France and Geneva. Later in life he became paranoid with delusions of plots conspired against him, as detailed in his Reveries of a Solitary Walker. He died a recluse, but by no means a hermit, as he still held his wife and a few friends dear.

Rousseau’s writings had a tremendous impact on Western culture. To him the idea of the “noble savage” is usually attributed; Rousseau imagined that man in his “natural state” – before society – was naturally good, in that such a self-sufficient man was not subject to the vices of politics and government. As such, things like his Discourse on Inequality have relevance to our Losties, stranded in the middle of nowhere and essentially forced to create a society all on their own. Indeed, the text of LOST seems to confirm Rousseau’s rebuttal of Hobbes’s contention that in the state of nature, with no civilization, all was “continual fear and danger of violent death; and the life of man, solitary, poor, nasty, brutish, and short”:

“There is another principle which has escaped Hobbes; which, having been bestowed on mankind, to moderate, on certain occasions, the impetuosity of egoism, or, before its birth, the desire of self-preservation, tempers the ardour with which he pursues his own welfare, by an innate repugnance at seeing a fellow-creature suffer. I think I need not fear contradiction in holding man to be possessed of the only natural virtue, which could not be denied him by the most violent detractor of human virtue. I am speaking of compassion…”

Our Losties have not been at each others’ throats since returning to a state of nature. Indeed, they’re pulled together remarkably well to live together (so as to avoid dying alone), despite the fact they’ve hived off into two camps at the Beach and at the Caves. …

We now begin what I consider to be the second act of LOST’s first season. The basic tenor of the show has now been laid out – our principal characters have been introduced in some detail, as has the mysteriousness of the Island, and the general tenor of the show’s approach to episodic serialization has been established. Overall, it’s been a story of how these survivors of a plane crash have adapted to living on an island in the South Pacific, touching on issues of social organization through intense characterization. Now the show begins to shift focus, adding new dimensions: not only will some of the mysteries introduced early on be revealed, but it starts exploring the implication of the fact that our survivors are not alone.

We now begin what I consider to be the second act of LOST’s first season. The basic tenor of the show has now been laid out – our principal characters have been introduced in some detail, as has the mysteriousness of the Island, and the general tenor of the show’s approach to episodic serialization has been established. Overall, it’s been a story of how these survivors of a plane crash have adapted to living on an island in the South Pacific, touching on issues of social organization through intense characterization. Now the show begins to shift focus, adding new dimensions: not only will some of the mysteries introduced early on be revealed, but it starts exploring the implication of the fact that our survivors are not alone.