Jadzia Dax and Doctor Bashir are taking time out from a camping trip in the Bajoran wilderness to visit a museum honouring the planet’s art, history and culture. Jadzia compliments the beauty of one of the pieces, whereas Julian tries to act like an art critic to impress her with his “knowledge” of different Bajoran styles. Jadzia is exasperated and, perhaps sensing he’s fucked up, Julian changes the subject. He asks her if any of her hosts went on class field trips to museums as children. Standing atop a towering balcony, the two gaze down into the museum below, where it just so happens one such field trip is underway right now.

Jadzia Dax and Doctor Bashir are taking time out from a camping trip in the Bajoran wilderness to visit a museum honouring the planet’s art, history and culture. Jadzia compliments the beauty of one of the pieces, whereas Julian tries to act like an art critic to impress her with his “knowledge” of different Bajoran styles. Jadzia is exasperated and, perhaps sensing he’s fucked up, Julian changes the subject. He asks her if any of her hosts went on class field trips to museums as children. Standing atop a towering balcony, the two gaze down into the museum below, where it just so happens one such field trip is underway right now.

It’s a large room, full of gigantic statues, all looming imposingly over the museum guests. A teacher is disappointed in her students, none of whom recognise the figure immortalized in stone before them. Her name was Charna Sar, who she says was a great hero of the Bajoran people whose name has been forgotten. The children wish to hear her story and the teacher obliges, but only on the condition they will continue to tell it themselves. The teacher begins the tale, saying the story of Charna Sar is intimately connected to that of a Cardassian by the name of Kotan Darek. We transition to a flashback, and return to the darkest days of the occupation. Darek has arrived at a prison camp, wishing to speak with a Bajoran prisoner named Charna Sar, which takes the camp’s commandant by surprise. Charna is a resistance member who’s been captured and sentenced to death, but Darek wants to pardon her, shocking both Charna and the commandant.

As they leave the camp, Darek explains that he’s been ordered to construct a orbital space station around Bajor that will serve as an ore processing facility. In addition to being in the resistance, Charna Sar is also Bajor’s greatest architect, and Kotan Darek wants her to help him build it, as well as serve as a liaison to the Bajoran labourers. Charna flatly refuses on the grounds the station would further the explotation and enslavement of her people, but Darek protests that the station will in fact automate the mining process, thus making life easier for those on the ground in the mines. Charna still isn’t convinced, but complies after Darek threatens to destroy the Barodeem, a library tower containing historical and cultural artefacts dating back centuries with a phaser blast (Darek then claims, however, that he would never have actually done it). The two leave for the station, which is already under construction. Darek says that it will be “the eyes and ears of Bajor and Cardassia’s greatest aesthetic triumph”.

Darek takes Charna aboard, showing her a common area under construction, and shows her the opulent quarters she’s been assigned, right next to his. After Darek leaves, Charna compliments his taste in clothing, and takes a look at the future Terok Nor‘s schematics. In keeping with a previous comment she made about the station being “typically Cardassian” and “function over form”, she extends the lengths of the docking pylons and takes a look at the air filtration systems. Meanwhile, Darek is in communication with a Gul Dukar, who is less than pleased with his employing of a Bajoran terrorist to help design their ore processing facility. Dukar says he should be alerting the Obsidian Order, but instead tells Darek to have Charna executed once she’s done, to which he agrees.

The next day Darek goes to see Charna first thing in the morning. As they make their way to Operations, Darek says he’s found out about the changes she’s made to the blueprints, and agrees with her alterations: Both respeccing the ventilation units to alleviate the strain on the Bajoran workers and her other design alterations. Soon, they meet a former comrade of Charna’s, a woman named Hester, who’s not happy to see her working with Darek, which she views as collaboration. Darek points out that while Charna may see her work on Terok Nor as helping the cause, Hester probably doesn’t view it the same way. Charna later goes to try and talk things over with her by way of explaining, but Hester won’t hear any of it. That is, unless, she’s willing to fight on the frontlines again. Charna gives the Bajoran resistance fighters the schedule of a group of supply ships, which does not go unnoticed. She’s formally disciplined in the Cardassian way (that is, brutally), but all Darek wants from her is to promise not to destroy Terok Nor until after it’s finished.

Darek takes Charna to his quarters, and shows her a hologram of the Obsidian Order headquarters, which he both designed and built. It was his greatest masterpiece, before Terok Nor, which he wants them to finish as quickly as possible: By working with a Bajoran, he’s made powerful enemies within the Cardassain government, and his allies will no longer be able to protect him. Charna is baffled that he would throw away his career for her, and asks him why. “Because we are the same,” Darek says. “Fate has made us enemies, but destiny has allowed us to pursue our love together. The creation of shape and form. To make something new from nothing, the power to build”. “How I would love to believe that”, Charna responds, “But you Cardassians have mastered an art that eludes us Bajorans, the art of destruction”. “That is the way of my species, and I must accept that”, he answers.

One month later, Terok Nor is finished, with both Charna and Darek marveling at how beautiful it is. Even so, Charna doesn’t want to be associated with it, claiming it’s “a product of Cardassian brutality, not Bajoran ingenuity”. Just then, Darek is summoned to meet with Gul Dukar, but warns Charna of something about him before he goes, though we don’t get to hear what it is. In the newly completed prefect’s office, Dukar relieves Darek of command without advance notice. The architect is then ordered to move *every Bajoran* on the station to Cargo Bay 6, again with no explanation. Indeed, Dukar even snarls that if he didn’t have friends in high places, Darek would be going with them. Dukar presses the Gul for the reasons why, and the infuriated commander spits out that Darek has compromised the safety of the entire station by employing Bajoran construction workers, and now they must all be disposed of. Darek leaves to fulfill his duty.

Gul Dukar takes his young son to watch the execution via a viewscreen looking in on the cargo bay. Dukar plans to depressurize the cargo bay, thus suffocating all the Bajorans inside. The child asks why not simply shoot them, and his father calmly explains that this way they can make it look like an accident. “What about the children?”, his son asks. “What of them?” the Gul asks in response. But before he can act, an elite team of Bajoran resistance fighters in stealth suits breaks into the Operations centre. Dukar orders them all killed and fires the first shot, cutting down one of the freedom fighters. The leader of the strike force responds by gunning down the Gul himself. Then Darek exclaims he’ll depressurize the bay if they resistance fighters don’t drop their weapons, and the leader tells her team to do as he says.

The next day, it’s revealed the resistance leader was, of course, Charna Sar, and, of course, Darek knew about it. They both comment on the roles history has forced them into playing. She knows he has to execute her, but he saved her people, which is all she cares about. And when they comment on the fate of Gul Dukar’s son, who “will continue the vicious chain, seeking the blood of Bajorans in vengeance for what he witnessed”, Charna implores her equal and opposite to tell the boy and all the others “Tell them what we had together. Bajorans and Cardassians must know that there is something better than hate. Something more than enmity”. He will, and promises to make her death painless. And she knows he will. Darek’s last words to her: “Through Terok Nor, Charna Sar, you will live forever…I will miss you”.

Back in the present day, the teacher tells her class that after this, Darek disappeared, his story only coming to light after his diaries were uncovered after an attack on the Obsidian Order headquarters. Some think the accounts contained are fabrications, but nobody alive today who worked on the construction of Terok Nor will repudiate their claims. She also says that Darek has become an unperson, his name going unmentioned in all official historical accounts and government records. One of the children asks what became of Gul Dukar’s son, but the teacher says that “is a story for another time”. Leaving the museum, Doctor Bashir ponders on the tragic story of Kotan Darek and Charna Sar. “I can’t help but think of the irony, Jadzia…The Cardassians built Terok Nor to exploit Bajor and now it may be what ultimately saves Bajor.” But the wise Trill doesn’t agree: “Terok Nor won’t save Bajor, nor will the Federation. It’s the spirit of the Bajoran people that will. A spirit that can never, and will never, be suppressed”.

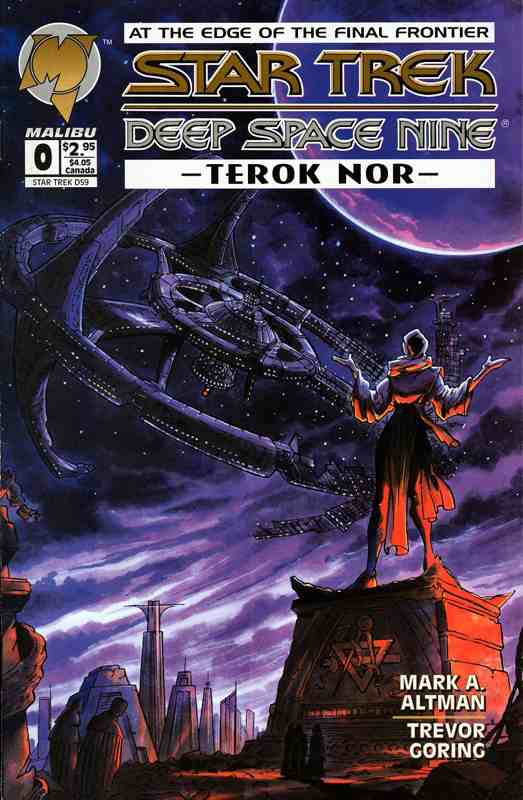

There is probably no greater honour to give Star Trek: Deep Space Nine than to have its final proper story be an Issue # 0. Much like “Emissary” at the opposite end of this era, “Terok Nor” is a story existing outside the bounds of time: Past, present and future exist simultaneously. A tale from the primordial history of Deep Space 9 itself and a lyrical exaltation to its highest purpose, yet bifurcated by a gatefold pinup of the USS Defiant and followed by an essay on the Dominion by the author himself. Bajor, and the Bajoran Wormhole, and beyond that, eternity. This is the last stop on our spiritual journey before we depart this plane of existence forever. The final task laid out before the waystation At the Edge of the Final Frontier is to sublimate itself: Deep Space 9 realises its own spiritual awakening, and vanishes into the Rainbow Moment.

The steward for the last part of our journey is, naturally, Mark A. Altman. And diegetically, Jadzia Dax. It is her and Doctor Bashir who I seem to associate with Altman’s work the most, and it seems very fitting that they should be our sole representatives of the Star Trek: Deep Space Nine status quo here. And “Terok Nor” has to be Altman’s masterpiece: As good as Hearts and Minds was and as much personal sentiment as I have for it, this is, to turn a phrase, on a different plane. Altman is helped immensely by artist Trevor Goring, whose work is breathtakingly painterly in a way I never see in comics. This is the best any Star Trek comic has ever looked. It is debatably the best Star Trek itself has ever looked. But, like Charna Sar and Kotan Darek, it’s what Altman and Goring create together that lasts the ages.

“Terok Nor” works via dream logic-Its plot points and core themes are conveyed not so much through exposition as they are through implied symbolic association. There’s the implication, never explicitly stated or shown, that the towering museum Dax and Bashir visit is the same Barodeem Darek and Charna visit before they leave Bajor. And then Julian’s disparaging comment about disliking “Bajoran expressionism” is juxtaposed with the fact Goring’s style for this book is overtly expressionistic, with enormous landscapes of hauntingly alien beauty paralleled with starkly realistic characters drawn in sharp contrast with heavy shadow and surreal lighting. It resembles neither the photorealistic look of Altman’s last Star Trek: Deep Space Nine story (and the Malibu series on the whole), nor the theatrical look of the TV series, nor the four-colour pulp look of DC’s Star Trek: The Next Generation series. “Terok Nor” is singular, and looks like no Star Trek story before or since.

There’s the utterly bold move to imply Darek and Charna conspired to kill Gul Dukar together. And not long after that, we have the subtle implication that Gul Dukar’s son grew up to be Gul Dukat (“That’s a story for another time”). We also get a reference to not just Garak (in Charna’s complimenting of Darek’s fashion sense) but also Quark (Darek telling Charna that he hopes to one day have a public establishment where people can relax and mingle as they walk down the future Promenade). References like these serve to make “Terok Nor” an elegant prequel that weaves itself into the pre-existing narrative unobtrusively and respectfully, but it’s the striking choice to have one of the Bajoran teacher’s students be named Bareil that really show’s the strengths of this approach, as it unbinds the story’s sense of linear time completely.

That scene takes place in the establishing shot of the museum, with two figures whom we are to assume are Jadzia and Julian looking down from the balcony (although this is never shown definitively), and comes directly after Bashir asks Dax if she ever went on field trips to museums. This links Bajor’s more distant past to its recent past as well as its present and future (and even those of Dax and Bashir, who are not “Bajoran”, but are perhaps “Of Bajor”), while the story’s general arc of moving from our regulars on the balcony to the teacher telling her story and then back to the regulars at the end mirrors Jadzia with the teacher and Julian with her students.

Perhaps then, the teacher did get her wish. Perhaps like all oral narratives, the story of Charna Sar and Kotan Darek’s forbidden love and the child born out of it is one that reaches back to the dawn of time, and forward into the next cycle as we all take our turn playing the role of the storyteller.

It is a story that lasts because it is imperative to our survival. All ancient stories pass on crucial knowledge and wisdom from one generation to the next. The story of “Terok Nor”, and that of Star Trek: Deep Space Nine, is that of healing, reconstruction and rebirth through giving birth. It’s about meeting and getting to know other people to help reveal facets in ourselves. It is about our journey to find ourselves and our purpose and learning how to incorporate those lessons into our daily lives. We all come from different lives and different worlds, and there will always be the need for a place we can all go to share our positionalities and create something new together out of them. This is what Deep Space 9 was made for: This is its truest purpose, and it is the story about how it was born under this dream such that the dream was built into its very being that reminds us of this.

Art and stories, compromised as they may be, offer us human-made symbols that can trigger memories of deeper things within us. Art may not ever be able to replace the eternal, but perhaps the best art can point us in the direction to find it within ourselves. And maybe, for some, they will remember that a small part of them will always have a home here on Deep Space 9.

Jadzia Dax and Doctor Bashir are taking time out from a camping trip in the Bajoran wilderness to visit a museum honouring the planet’s art, history and culture. Jadzia compliments the beauty of one of the pieces, whereas Julian tries to act like an art critic to impress her with his “knowledge” of different Bajoran styles. Jadzia is exasperated and, perhaps sensing he’s fucked up, Julian changes the subject. He asks her if any of her hosts went on class field trips to museums as children. Standing atop a towering balcony, the two gaze down into the museum below, where it just so happens one such field trip is underway right now.

Jadzia Dax and Doctor Bashir are taking time out from a camping trip in the Bajoran wilderness to visit a museum honouring the planet’s art, history and culture. Jadzia compliments the beauty of one of the pieces, whereas Julian tries to act like an art critic to impress her with his “knowledge” of different Bajoran styles. Jadzia is exasperated and, perhaps sensing he’s fucked up, Julian changes the subject. He asks her if any of her hosts went on class field trips to museums as children. Standing atop a towering balcony, the two gaze down into the museum below, where it just so happens one such field trip is underway right now.

March 29, 2017 @ 10:37 pm

And here is clearly another story I need to get hold of.

The idea of the station being the result of such a collaboration – a union of people ground between the gears of empire – is extraordinarily astute. It means DS9 really does belong there. It is not something that was hijacked and forced to play a role it was not meant to, as Gul Dukat will always insist, but rather that time and change have conspired to uncover what it was truly built for.

I think I could gaze at that cover alone for a long while. The ghost of the station haunting the sky of Bajor above the statue of its mother, which cannot of course exist simultaineously with the apparition. But then all ghosts are juxtapositions and prophecies are often paradoxical.

Lovely.

May 13, 2024 @ 3:59 am

To address these challenges, assignment writing services site like http://www.12y.org/ have emerged as a valuable resource for students. These services consist of professional writers and subject experts who have a deep understanding of the expectations and requirements of academic assignments. They provide students with guidance and support in organizing their ideas, creating a well-structured plan, and designing a visually appealing assignment.