No Way Forward (Book Three, Part 56: Really and Truly)

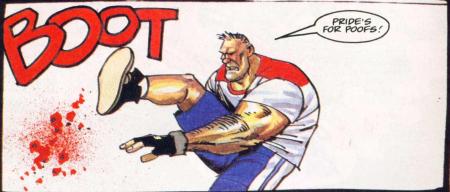

Previously in Last War in Albion: Morrison did the worst work of his career with the recklessly offensive and bullying Big Dave.

A nervous breakdown. There is no way forward. We must set the action in reverse. -Alan Moore, The Birth Caul

Whatever its moral flaws, Big Dave, along with Maniac 5, were the two most popular strips of the Summer Offensive, and so like Maniac 5 it saw itself trotted out for return engagements. This began with the one-off “Young Dave,” a story of Big Dave’s childhood, which appeared in the 1994 annual, followed by two more four-part stories in 1994. These stories moved away from the sheer and over the top big concept premises of the original two strips, finding their humor instead in putting the title character in juxtaposition with iconic parts of British lad culture. The first, “Costa Del Chaos,” sees Big Dave holidaying in Tenerife, while the second, “Whole Lotta Balls,” sees him storming the World Cup to win it for England and defeat the Germans. Tonally both are similar festivals of cynical and calculated offense to the original, but there’s a creeping sense of desperation and trying too hard, as if Morrison and Millar were simply trying too hard for something that neither deserved it nor, truth be told, wanted it. Morrison validates this sense, admitting that “Big Dave clearly had to die. Mark and I were goading each other on every day to break some new bad taste taboo, We both have pretty fucked-up notions about what’s funny and what isn’t. It got to the point where we wouldn’t be satisfied with a Big Dave pitch unless one of us was really badly shocked. We were barely aware that our audience didn’t necessarily want to go as far as we would have liked.”

Mercifully, 2000 A.D.’s editors eventually grew to blanche at their enfants terrible, and pulled the plug later that year. Morrison has suggested a variety of ideas that might have come out otherwise—“Planet of the Darkies,” which Morrison described as “Dave gets sick on a bad kebab and imagines returning from space to a world taken over by immigrants,” “Battleground Bulger,” which saw miniaturized Dave and Saddam Hussein fighting inside the body of a dead toddler, and a story for the 2000 AD Yearbook called “Cheryl-Anne’s Big Night Out,” which saw Big Dave trying to kill Salman Rushdie. This story, which apparently got as far as Steve Parkhouse drawing it, was the one that actually served as the breaking point, with Fleetway head Chris Powell rejecting the story, which largely coincided with both Morrison and Millar ceasing to work with the company, with Morrison going so far as to suggested that he was “blacklisted at 2000 A.D.”

And indeed, their future treatment at 2000 A.D. largely bears this out, at least in the short to medium term. Perhaps the most striking example comes with the strip Janus: Psi-Division, featuring the psychic judge they introduced in Inferno. Morrison wrote a one-off for the 1993 Winter Special, and another one-off that appeared in 1995, while Morrison wrote a short arc that appeared in 1996. A larger story, co-written by Morrison and Millar with art by Chris Weston, was planned for the DC-published Judge Dredd: Legends of the Law, but that book got cancelled before it saw print and the project migrated back to 2000 A.D. where it was viewed as so low a priority that rather than having Weston finish his pages or have the project’s new artist, Paul Johnson, redraw them they simply dropped the first third of the story, running it in 1997 as part of a glut of inventory stories cleared out before the magazine changed paper sizes. This was perhaps harsh on a story that had no obvious or glaring flaws, but equally, it wasn’t exactly long on virtues either—some weird ideas, most obviously the cosmic Judge Angels, but nothing that fits together or feels like anyone was trying too hard. Nevertheless, that Fleetway would be so disinterested in a comic by one of the stars of the British industry speaks volumes about how frosty Morrison’s relationship with the magazine had become.

For all that Morrison and Millar were the primary names behind the Summer Offensive, it was in practice a three party effort, with one strip, Slaughterbowl, contributed by John Smith. Smith is one of the forgotten men of 90s British comics. He’s appeared fleetingly throughout the post-Watchmen story—he was the writer of New Statesmen, the original co-feature of Crisis along with World War Three, and penned a fill-in issue in the middle of Ennis’s Hellblazer run. But for the most part his career never quite caught fire—his flagship effort in the American market was an eight issue Vertigo miniseries called Scarab that, by Smith’s own admission, was “a fiasco from beginning to end,” and he spent most of his career in the British market writing for titles attached to 2000 A.D.

As Smith explains it, he became involved in the Summer Offensive because he was friends with Millar at the time. He was, however, emphatically marginalized in the promotion—when Comics World did an interview promoting the project, for instance, it was with Morrison and Millar, not Smith. To some extent that’s understandable—Morrison and Millar were collectively responsible for four of the five strips in the Summer Offensive, after all. And sure, Morrison’s joke when asked about Slaughterbowl that “the real tragedy is that John could have been with us if only you’d known to bring a Ouija board, Martin. John died recently in fairly unsavoury circumstances” is probably a bit rough given that Smith could surely have used the promotional boost, but it was a cheeky and irreverent interview, and these things happen. That this was followed by Millar going on a riff about how “I’m glad he’s dead” and how “but that whining nasal voice really got on my tits” is, however, downright shocking, to the point where it formed the only point in all the fuss around the Summer Offensive where Morrison seemed to balk at Millar’s antics, repeatedly chastising him to drop the bit, albeit to no avail.

The irony here is that Slaughterbowl is a quiet highlight of the Summer Offensive. In many ways it is best compared with Maniac 5, with which it shares an aesthetic of aggressively straightforward action. But while Maniac 5 used (or at least tried to) its action sequences to mask a fundamental emptiness of the premise, Slaughterbowl takes a giddy “more is more” approach to the task. Its premise sees convicted criminals competing in gladitorial combat atop robot dinosaurs for a chance at money and freedom, a setup that is ridiculous, but that is also tailor made for visual excitement. To add a satisfying contrast to proceedings, the protagonist is a man named Stanley Modest, who, as the name suggests, is not exactly the sort of hardened and brutal criminal who on robo-dinosaur death matches. Indeed, he’s a meek greeting card writer who’s in the eponymous Slaughterbowl to try to finance his sick wife’s medical care. He is, admittedly, a serial killer, but in a fundamentally realistic sense, which is to say a reedy and pathetic man as opposed to a hulking action hero badass.

It’s a charming strip, although one can see in it how Smith might have a career ceiling. For all the strip’s gloriously dumb populist appeal, there is a constant sense that Smith is overthinking it, unable to quite relax into doing the big dumb action extravaganza that he’s created a perfect premise for. It is in many ways like Peter Milligan only moreso—a writer of evident talent and cleverness that can’t quite get out of his own way or land the premise. Slaughterbowl is a highlight of the Summer Offensive, yes, but that relies on the fact that the Summer Offensive was largely a disaster.

The final strip in the Summer Offensive was Really and Truly, which saw Morrison reuniting with their Dare collaborator Rian Hughes for what they described as “the light, buzzy strip, with lots of pop culture references and a kind of breezy pointlessness to it all.” This was a brightly colored bit of 1960s nostalgia with a threadbare plot of two crack operatives, the eponymous Really and Truly (of whom Morrison proudly notes that they “don’t even know which one’s Really and which one’s Truly”) trying to drive a car full of drugs (including bullets you put in your ear to download pop songs) up to San Francisco for the annual Burn Out on behalf of the communists who run the entirety of pop culture. This image has roots in the 1960s iconography, but by 1993 would have been more directly connected with the rise of rave culture (and tellingly, the bullet songs are specifically called “mixes”, a point Morrison emphasizes when they describe the aesthetic goal as “ a strip which approximated the experience of taking Ecstasy.”

Ecstasy—the street name for 3,4-Methylenedioxmethamphetamine—was first developed in 1912 by the drug company Merck, where it was an unsuccessful drug for stopping bleeding. It sat largely unnoticed in the company’s patent archive until the 1970s, when its psychoactive effects were discovered and it began seeing recreational use in the Chicago area. This sparked research into its utility for psychotherapy, where it showed promise in treating PTSD, which in turn spread knowledge of its recreational value, and in the early 1980s it found its niche as a club drug. Its effects—euphoria, mild visual hallucinations, and a burst of energy—made it a nigh perfect drug for a dance party, and it took off, repopularizing dance parties with it.

In 1987 the drug hit Manchester, where it collided with the burgeoning club scene centered on Factory Records’ Haçienda nightclub, sparking the Madchester scene and, the next year, the Second Summer of Love as rave culture exploded across British pop culture. This was the cultural moment out of which Fleetway’s retro-60s Revolver had sprung, and is understandable at least in part as the first direct repercussion of the magical explosion that was Watchmen, a point captured by the embrace of the yellow Harvey Ball smiley face as a symbol, which was even sporting the trademark blood stain on the cover of Bomb the Bass’s acid house hit “Beat Dis.” This was one of the major shifts in the nature of drug culture within the 20th century, second only to the early 70s transition from LSD to cocaine. But while the rise of rave culture was liberatory in the context of the right wing hegemony of the Thatcher/Reagan/Bush/Major years, it was fundamentally a hedonistic turn without much in the way of larger political investments. Or, as Morrison put it describing Really and Truly in terms of ecstasy, “it’s light and it’s loveable and makes you want to dance, but when you come down you realise you haven’t learned anything. To that end I wrote the entire eight episodes in one day, out of my face on snowballs. It’s summery and superficial, but in a way which I hope will recall those dance records you just can’t get out of your head.”

It’s easy to miss the most significant part of this, however, which is that Morrison wrote the strip on drugs. This was a marked contrast to Arkham Asylum, which they noted that they wrote “late at night and after long periods of no sleep” because they were “straight-edge to the core and the only way I could approximate a genuinely deranged consciousness was via the use of matchsticks between the eyelids.” And it’s telling that their early comics, for all they regularly dealt with weirdness, were not especially psychedelic or focused on drugs—the peyote trip in Animal Man is the only real exception. This was a later change, in the wake of their career success—they describe how “it took me until I was thirty to decide I’m gonna start drinking, I’m gonna start taking drugs, I’m going to see what life is like for other people.” This sparked a wealth of life changes—they broke up with their girlfriend, began traveling, and more broadly began to fully embrace the ostentatious persona they had previously only played in Drivel columns and occasional interviews.

With Doom Patrol largely plotted out since 1988, this change took a while to actually appear within their comics, just as it took a while to actually unfold. (The perhaps definitive event—shaving their head just before they departed on the trip around the world that would famously lead them to Kathmandu—took until early 1994.) Nevertheless, the Grant Morrison who wrote Really and Truly was clearly a markedly different person than the far shier and more uncertain figure who had caught the train down to London to meet with Karen Berger and Dick Giordano six years earlier. This was Grant Morrison as comics rock star, brash and confident, fully absorbed by the character they had chosen to play. The psychedelic chaos magician, so much larger than life, ready at last to fight a War. [continued]

November 21, 2022 @ 8:19 am

The great thing about Slaughter Bowl is the twist. At the, start it looks like Stanley is being set up by the government as a Serial Killer, but nope it’s no he’s actually guilty!

November 21, 2022 @ 6:29 pm

there is a constant sense that Smith is overthinking it

Or maybe just that he’s out to please himself and doesn’t particularly care whether the reader can keep up. I have all five issues of new statesmen‘s US release, and it embodies the passage from the introduction to Sandman #8 about how “We come in in the middle, after the lights have gone down, and try to make some sense of the story so far. Whisper to our neighbours ‘Who’s he? Who’s she? Have they met each other before?'” Except that, with Smith as your neighbo(u)r, he gleefully confessed in a text piece that he’s more likely to show you “a picture of the Queen’s corgis encrusted with semen”, captioned O COME ALL YE FAITHFUL, than to give you any context for the world of 2047 (once removed) that wouldn’t naturally emerge from talk such as human beings would be likely to talk in the given circumstances. There are probably better ways to learn that Brenda (as the Welshbian on the Milliways discord used to call her) kept corgis.

(Of course, he did eventually break down and give us an epilogue, published as prologue to the US edition, in which one of the surviving Optimen talks to a now-grown throwaway character from an early chapter. I can’t say which position fits it better. I can only say that it greatly reduced the sense of alienation that must have haunted people reading it in Crisis, or at least made it indistinguishable from the normal alienation I experienced living on Earth with my autism diagnosis a decade away.)