Dagorlad

Name: Dagorlad

Location in Peter Jackson films: Tongariro National Park, Te-Ika-a-Māui.

Summary: A treeless plain to the northwest of the Black Gate. A lot of epochal battles are fought here. It is not considered by anyone a nice place to visit.

Unlike previous stops on our odyssey, Tolkien dedicated scant time to describing the stark plain of Dagorlad. It’s a historical battlefield, renowned for the important events that happened on its grounds, with little to distinguish it topographically. I can attest to the banality of preserved battlefields — I grew up near Manassas National Battlefield Park in Virginia, the site of two American Civil War battles fought in 1861 and 1862, and most of the spectacle there is forestry and split-rail fences. Travelers stop here because of what it stands for, namely two military victories of white supremacist separatists. The Confederacy’s victories at the Manassas battlefield went beyond merely strategic (perhaps unsurprisingly — the Confederacy was a structural clusterfuck): they saw the canonization of Stonewall Jackson, a deranged general renowned for standing his ground in battle before eventually getting shot by his own men and dying of pneumonia.

But our subject is a different white supremacist war with an exponentially smaller bodycount. Sauron’s corruption of Númenor is the apex of his fight against Elves and Men. Númenor, the apex of mortal Men in Arda, is an Atlantis-type legend in The Silmarillion and an expression of the corrosive effects of evil typical of Tolkien’s Catholic theodicy — starting noble and godly, then falling to temptation and the hubristic whims of godless men. Sauron’s influence inevitably corrupts it, and by the time of The Lord of the Rings Númenor has fallen into the sea. Stylistically, Númenor shares Mordor’s trait of being defined by its absence and obviation. Its presence is keenly felt, but as a concrete presence it has long since perished. The war against Sauron is a culture war: the Second Age of Middle-earth concludes with the Battle of Dagorlad, the culmination of a seven-year siege of Mordor by the Last Alliance of Men and Elves, an act of vengeance for the lost kingdom of Númenor.

Dagorlad, a nondescript plain, fills in for Númenor and other fallen scions of the West. It’s where their deaths are litigated in great, bloody battles. Nothing happens here because everything happens here. It’s worth noting that Tolkien, while writing stories full of wars and great heroic deeds, spends relatively little time on descriptions of his villains and battles. Certainly some of this is down to Tolkien’s non-normative idea of heroism, a staple of his work. The Hobbit is a story of a protagonist being thrown into the wrong story, his novella Farmer Giles of Ham sees a misanthropic farmer completely abject traditional notions of heroism, and The Lord of the Rings lacks a central protagonist after The Fellowship of the Ring. The Fellowship’s split sees Tolkien forge a narrative where war severs close personal ties and individual heroism is an ahistorical folly.

Tolkien’s own views on war were fairly clearcut. Having survived the Somme and trench fever, unlike virtually all his close friends, war was certainly a source of trauma for him. Battle passages in The Silmarillion and The Lord of the Rings are fleeting, limited to descriptions of character moments and dialogue rather than much of the action. Tolkien’s correspondence was tainted by disgust at war, particularly when writing to his son and future estate majordomo Christopher, who served in the Royal Air Force. In a 1945 letter to Christopher, Tolkien aired some of his fears and disgust with the Western military-industrial complex, with a dash of self-aggrandizing Rings referencing:

…It is the aeroplane of war that is the real villain. And nothing can really amend my grief that you, my best beloved, have any connexion with it. My sentiments are more or less those that Frodo would have had if he discovered some Hobbits learning to ride Nazgûl-birds, ‘for the liberation of the Shire.’ Though in this case, as I know nothing about British or American imperialism in the Far East that does not fill me with regret and disgust, I am afraid I am not even supported by a glimmer of patriotism in this remaining war.

The Letters of J. R. R. Tolkien, 100

Tolkien’s “sub-creation,” stemming from his dedication to a Catholic understanding of God as the only true creator, was more than a pet project. To him, it was an alternate universe: a realm where he got to play with his view of history and make what he viewed as improvements to the world. Crucially, these improvements don’t mean a removal of difficulty or moral hardship: Middle-earth is at war for much of its existence. Tolkien’s antipathy to war doesn’t pertain to a disdain for all players involved, but the most valorous characters,such as Frodo and Aragorn, would rather rest at home or govern justly than fight great battles.

Dagorlad is a case study in Tolkien’s view of grace and wartime heroism, particularly what Tolkien deemed “eucatastrophe,” a neologism he coined to describe a “good catastrophe” wherein the worst fates are narrowly avoided by acts of grace. Gil-galad and Elendil, Kings of Elves and Men respectively, both die at the Battle of Dagorlad in the final assault on Sauron. After a seven-year siege, the Last Alliance loses its leaders to the hand of Sauron himself. As usual with Tolkien, salvation comes from a heretofore insignificant person, in this case, Elendil’s son Isildur. The prince cuts off Sauron’s Ring finger, in a spectacular display of “ending a war with a relatively minor combat wound,” and dissipates Sauron’s power for centuries. Yet even then the victory is only partial: Sauron’s spirit wanders Middle-earth until he’s ready to rebuild his empire, and Isildur’s refusal to destroy the One Ring directly leads to the events of The Lord of the Rings. Total victory doesn’t exist in Tolkien’s mythos; all victories are conditional, as I showed in the prologue of this series. Tolkien’s mythology repudiates history as a series of definitive beats and trumps. Eras of Middle-earth ebb and flow into each other, paying off their debts as they progress. Even as Tolkien embraces a largely traditionalist ideological view, his treatment of history is nuanced and powerful.

Peter Jackson’s historiography is a different machine. While far from pro-war or even particularly reactionary (or at least, any more reactionary than Hollywood mainstays Steven Spielberg or George Lucas), Jackson’s films are grounded in a history of cinematic spectacle, making the action-adventure genre of filmmaking ground zero for a discussion of history and psychology. While Jackson’s films retain much of the moral core of Tolkien’s novels, and tone down much of their reactionary content, Jackson’s love of cinematic spectacle leads him to spend more time on the battle sequences than perhaps Tolkien would have appreciated (it’s probably this tendency that caused Christopher Tolkien to disparage the Lord of the Rings films as “gut[ting] the book, making an action film for 15-to-25-year-olds”). There’s no inherent problem with this; Jackson would have been a damn fool not to make Rings an action franchise, and The Two Towers’ rendering of Helm’s Deep remains an unparalleled achievement in blockbuster filmmaking nearly two decades after that film’s release. It simply means that Peter Jackson’s The Lord of the Rings is fundamentally a different narrative project than J. R. R. Tolkien’s The Lord of the Rings, and is both enriched itself and does the book a favor in the process.

As with most adaptations, Jackson’s Rings films significantly truncate their source material. This mostly pertains to plot structure, particularly the films’ sage choice to cross-cut the novels’ storylines (as opposed to Tolkien’s frankly baffling decision to do the Rohan/Gondor plots and Frodo and Sam’s journey as discrete blocks) and geography. Let’s deal with the latter here, as it pertains to how Jackson films the Battle of Dagorlad. In The Fellowship of the Ring’s prologue, the Battle of Dagorlad is fought “on the slopes of Mount Doom,” whereas Tolkien places Dagorlad outside the Black Gate, several miles away from Mount Doom. It’s effective filmmaking: keeping Mount Doom in the audience’s mind shortly after its first appearance as Sauron’s forge. The icons of Mordor — Sauron, the Ring, Mount Doom, and orcs — are introduced in one sequence. The battle itself is a montage that amounts to little more than a pale anticipation of what’s to come — it’s hard to envision Helm’s Deep and the Pelennor Fields at this point.

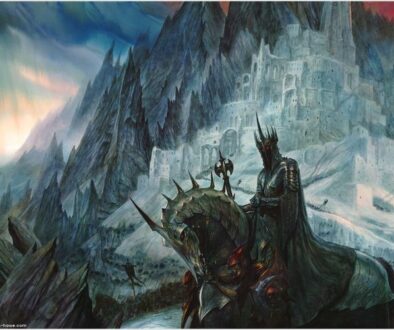

What sticks out most is the depiction of Sauron. There are no head-on shots of him — he’s depicted through composer Howard Shore’s motifs, some shots of his hands and eldritch helmet as he flings around elves and men with a death metal-style mace, and quick cuts by editor John Gilbert. Sauron’s design (a wonder of gothic rendering by Weta Workshop) sticks in the mind but pointedly never appears onscreen for more than a few minutes. In a couple short minutes, The Fellowship of the Ring utilizes cinematic techniques to depict Sauron’s impact in lieu of Sauron himself, similarly to how Tolkien writes Sauron, while also doing things with the character that would have faintly scandalized Professor Ronny-boy.

Sauron’s performance at Dagorlad seems to have made waves outside of Middle-earth as well. The Dagorlad scene was shot at Tongariro National Park, a staple of New Zealand’s North Island. Tongariro is the oldest national park in New Zealand, and the location of numerous Māori sacred sites. Disturbance of the region by The Lord of the Rings’ production led part of Tongariro to be deemed “Orc Road.” Conservation efforts have been made and led to some stunning achievements in the area. Yet it goes to show that touted values don’t always equate to actions. Tolkien’s love for the environment deferred to his preference for a kind of monarchical feudalism, which doubtless would do the environment no favors. Jackson, while sticking to Tolkien’s themes, disturbed New Zealand’s environment somewhat. Oftentimes, in the pursuit of crusades, the need for conquest shows itself in full livery, ready to step over anything in pursuit of its own arbitrary hunger.

June 4, 2021 @ 8:39 am

“Elendil and Gil-galad, Kings of Elves and Men respectively”

You’ve got them switched around.

June 4, 2021 @ 11:02 pm

Fixed. Thanks!

June 6, 2021 @ 11:52 pm

Really enjoying this series; if/when I read the books someday, I can imagine I’ll find it an essential guide.

The last paragraph made me think of Mad Max: Fury Road and the alleged negative environmental impact on the Namibian Desert by the production; a great work (one of my favorites, at least) with its heart in the right place, but perpetuating the very cycles it serves as a statement against. I’ve grappled with how I feel about that for some years now, and your recounting of the impact on Tongariro does a good job of putting that in perspective.

June 8, 2021 @ 3:08 pm

(as opposed to Tolkien’s frankly baffling decision to do the Rohan/Gondor plots and Frodo and Sam’s journey as discrete blocks)

Well I guess it depends upon whether you look at it as one single work or a six book series? Each volume is clearly a discrete block – and, barring the last, they each have a cracking cliffhanger too! It’s just that we are so used to seeing them in the “trilogy” form (which may actually do the structural design of the story a serious disservice!) that this doesn’t necessarily register as strongly as it perhaps should. You certainly lose a lot of the literary stylistic fun as Tolkien shifts his genres around for each separate “book”.

And consider how much less effective the ending of Book IV would be if we hadn’t spent the last 200 pages trudging through the swamps with Frodo and Sam, and how fantastic the end of Book V is when we have absolutely no idea what has been going on in Mordor.

Sure, the Jackson version couldn’t completely do that – they broke a lot of rules but even I don’t think they could have gotten away with following that model, especially whilst the whole project was still such a gamble during preproduction. And yet they give it a decent shot even so.

But I don’t think Tolkien’s decision is remotely baffling; it seems to make perfect structural and narrative sense.

(Still loving this series and appreciating your slant.)