Private Ownership of the Means of Inhumation

or

Sex, Death and Rock ‘n’ Roll – Part 2

(Part 1 can be found here.)

Some disjointed observations about ‘Revelation of the Daleks’; fragments of a larger and uncompleted essay that’s been in the draft drawer for ages… just so that I can say I’ve served up more this month than an off-the-cuff whinge about how much I hated P.E. lessons.

Hang the D.J.

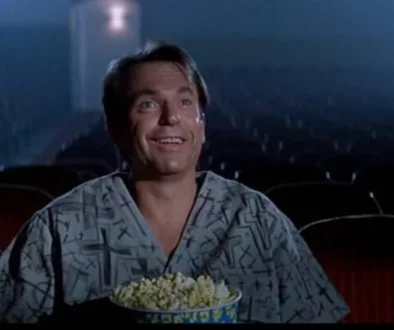

He skulks in his private studio. He almost prefigures RTD’s quasi-fan characters. He’s a geek, a dweeby enthusiast. He sits alone, watches TV, greets a visitor very shyly and comes alive when given a chance to enthuse about his pet obsession: the old style D.J.s and music of America. When he learns that Peri is really American, he reacts like… well, like a Who fan meeting Nicola Bryant. You get the feeling that he might ask for her autograph. He’s almost a parody of the nerdacious loner. He has little or no direct contact with any of the other characters. Apart from Peri, he’s only ever seen with Jobel – and they don’t speak to each other. One gets the sense of someone asocial and detached, always watching the goings on around him but never getting personally involved. In a way, he’s like an anti-Davros. Both are holed up in their personal hideaways, watching everything via cameras, commenting on the action like choruses… but from different perspectives. Where Davros schemes and snarls and giggles at the suffering of others, the D.J. takes the piss out of his place of employment and plays around with words, songs and personas.

He skulks in his private studio. He almost prefigures RTD’s quasi-fan characters. He’s a geek, a dweeby enthusiast. He sits alone, watches TV, greets a visitor very shyly and comes alive when given a chance to enthuse about his pet obsession: the old style D.J.s and music of America. When he learns that Peri is really American, he reacts like… well, like a Who fan meeting Nicola Bryant. You get the feeling that he might ask for her autograph. He’s almost a parody of the nerdacious loner. He has little or no direct contact with any of the other characters. Apart from Peri, he’s only ever seen with Jobel – and they don’t speak to each other. One gets the sense of someone asocial and detached, always watching the goings on around him but never getting personally involved. In a way, he’s like an anti-Davros. Both are holed up in their personal hideaways, watching everything via cameras, commenting on the action like choruses… but from different perspectives. Where Davros schemes and snarls and giggles at the suffering of others, the D.J. takes the piss out of his place of employment and plays around with words, songs and personas.

(There are a lot of these chorus/voyeur characters in 80s Who, from Arak and Etta in ‘Varos’ up to the culmination of the trend in ‘The Trial of a Time Lord’, which sees the Doctor himself become a member of the audience watching his own adventures on television!)

The other thing the D.J. does is play. He plays records, plays at disguise, plays at dressing up, plays at accents and attitudes and styles. This seems to be partly for his audience and partly for his own amusement. He comes over as a childman, an innocent. He’s not unaware of “the humanoid female form” but mentions it to “those of you who appreciate” it. He’s not personally interested, or his desire is submerged, or he’s too shy. His reaction to Peri is appreciative, but the oily, wandering-handed, heavy-breathing, harassing lust of Jobel is a counterpoint that throws the D.J.’s childish reaction into sharp relief.

Mind you, he’s not so innocent that he doesn’t know what’s going on and he clearly has no vociferous loyalty to his employers. He finds the notion of bodysnatchers making away with a cadaver rather funny and makes no effort to report them to his superiors. His off-mic comments to himself about George’s wife show that he’s savvy about the kinds of people his workplace caters for. To him, Tranquil Repose is a job. Okay, it’s a job that he has somehow managed to warp around his own personality and in which he plainly finds some pleasure, but essentially this guy is a working stiff.

In fact, this story is full of working stiffs (who work with stiffs). Almost all the relationships are economic. They are relationships between business partners, between boss and secretary, knight and squire, hitman and client, owner and manager, manager and staff. Even the relationships that are not blatantly exploitative are still tainted by their economic nature. Vogel plainly performs more than secretarial duties for his Sunset Boulevardy dominatrix boss, but her reaction to his death is to complain – albeit sounding shocked – about the difficulty in finding such good help. Apart from Peri and the Doctor, and the friendship that Peri strikes up with the D.J., the only entirely non-economic relationships are between Natasha and Gregory (they talk like dissidents or rebels) and between Natasha and her father.

The Capitalist Way of Death

All these economic relationships (with the exception of Orcini and Bostock, who seem like relics of a feudal order) look like they’re based on wages. Wages are never specifically mentioned (unless you count Orcini’s fees… which I don’t because they’re payment for services) but it is implicit that Takis, Lilt, Vogel, etc., are all being paid for turning up in the morning. Even Jobel is clearly a senior employee rather than the proprietor. These employment relations, along with the fact that Kara and Davros are both clearly in private business, place the story in a highly capitalist world.

Doctor Who doesn’t always depict the future as capitalistic. Many Who stories set in the future (or on other planets) seem to show a post-economic world in which people just exist in societies which lack forces of production, distribution and exchange (Marinus, Atrios, Karfel); or which achieve such things by a kind of tacit, quasi-magical, hyper-technological advancement (Gallifrey… unless, as I suspect, the unseen Shabogans do all the actual work); or through some dastardly trick which becomes the focus of the plot (Zanak, the Elders); or through the providence of some hidden exploiters (the Krotons, the Macra); or the dirty work is done by a slave class (Inter-Minor, Thoros-Beta, Kaldor City). Of course, this is because the writers are less interested in intricate worldbuilding than in creating drama or developing their big concepts. Who comes from myth, children’s fiction and B-movies: nobody is interested in who manufactures the stirrups for the horses in Narnia, or how much they get paid for doing it. In historicals and present-day stories we occasionally get some sense of economic relationships. We are, at least, more likely to meet characters with jobs (like Anne Chaplet) or with executive positions (Hibbert of Auton Plastics for example).

But sometimes, Doctor Who takes us to future societies with recognisable forms of economic organisation. Sometimes it is feudalism, as on Tara and the planet in E-Space where the Three Who Rule lord it over their peasants. But occasionally we encounter some of the recognisable hallmarks of capitalism: wage labour, industrialised or technological capital in private hands, large scale financial transactions, mass media and conspicuous consumption. Every one of these markers is to be found in ‘Revelation of the Daleks’.

Necros is obviously part of a wider interplanetary economy which is based on the capitalist mode. Davros appears to have somehow bought-out the old management of Tranquil Repose. He owns (or at least controls) the means of inhumation. He presumably pays the wages of the people that work and train there, including the D.J. who represents the media, supposedly relays news and current events to his ‘listeners’ and appears as a selling point in the advert that is played for the Doctor and Peri. Davros is involved in a direct financial partnership with another firm, Kara’s food producing company. He funds his work (R&D, one might call it) with investments from Kara alongside the profits that TR presumably makes from selling funerary services. The death business is big money for him, just as it is in our society. Anyone who has read Jessica Mitford’s classic The American Way of Death will know that the funeral industry was (and is) rife with abuses and swindling; moreover, it is a mass service industry (no pun intended). It is an emblem of the capitalistic way in which our basic needs and feelings are appropriated by business, reconstituted and then sold back to us. It is thoroughly consumerist. Your average grieving consumer gets stung, in their most desperate and vulnerable hour, for spurious extras like airtight coffins (which often explode owing to a build up of gas within) or velvet pillows upon which the oblivious dead can eternally lay their unfeeling heads. Meanwhile, the financially overloaded – remembering, perhaps, the old dictum “if I can’t take it with me, I don’t want to go” – can (theoretically) stump up for any bizarre posthumous luxury that their hearts desire. You can have your ashes shot into orbit. You can pay of a private mausoleum. Wanna be frozen in the hope of one day being defrosted, cured and welcomed back to the head of the boardroom table? There are companies that claim to be able to provide this service… well, they can freeze you after you’re dead anyway. The rest of it… well, you’re gambling on future technology that can both thaw you out and then cure death… and on anybody in the future thinking it would be a good idea to bring back someone stupid and narcissistic enough to have themselves frozen in the first place. And then there’s the concern raised in ‘Revelation’: would the living want their dead/frozen rivals to be resurrected? There’s an urban legend that Walt Disney was frozen and stored under Disney World. Imagine how the current President and CEO of the Walt Disney Company would feel if told that Uncle Walt was ready to be defrosted and resume his old position. I imagine he or she’d be quite keen to keep the old man on ice.

Consumer Resistance is Useless

One of the wider points here is to do with the consumerist cycle of representation, which latches on to human needs, commodifies them, rebrands them, turns them into images and ideology, and then feeds them back to the consumer via the media. The strange thing is that, in the process, the needs themselves are lost in all sorts of ways. The human need to take in liquids, the human desire to take in pleasant-tasting liquids… this is the basis of soft drink adverts, but what are soft drink adverts really selling? Anyone who has read Naomi Klein’s No Logo – and the literature that followed in its wake – will be familiar with the fact that many corporations do little actual production. The dirty task of actually producing the commodities is farmed out to other companies, often based in Third World countries with no pesky labour regulations, where they can work the local paupers longer and for less money, often at the sharp end of vicious bullying, sometimes corralled in virtual concentration camps. The corporations then buy the products that are produced under conditions of virtual slavery and flog them on the Western market for inflated prices. The process has many advantages for capitalists. The less they personally spend on production, the more surplus value they pocket when their products are sold… the more domestic jobs they destroy (or threaten to destroy) the more they can blackmail their remaining domestic workers to accept lower pay, longer hours, harder work and lower job security… and they can carry on selling their primary product: brand images. That’s what corporations tend to produce and market now: brand images and identities. They market the idea that certain brands (and their products) embody and thus confer certain values and philosophies. This is why adverts try to associate their products with desires, aspirations, trends and ideas that are seen as popular. One of the ironies here is that, while the images in adverts are often designed to appeal to our basest urges or our prejudices, they can also reflect values diametrically opposed to the values actually practiced and pursued by the corporations that produce them. Clothes manufactured under ghastly conditions by bullied, repressed, half-starved, overworked, brown-skinned unpeople are marketed to the Western consumer with inspirational images that reflect public concerns like anti-racism, egalitarianism and rebellion against authority. Gorgeous models throw molotov cocktails at menacing riot police while backed by 60s tunes about revolution; hunks rescue innocent Asian children from oncoming fascist tanks… be like these inspiring (sexy) heroes, the ads imply, by wearing the same mass-produced, overpriced jeans.

Okay, I’ve galloped off on a hobby horse… but there is a point here. In the age of the mass media and branding, consumerism is cannibalistic. It makes us consumers not only of products, but of our own images. It feeds us images of ourselves, altered and doctored to fit a certain agenda, but recognisable as us, or as the kind of people we want to be, or as the kind of people that they want us to think of as normal. They sell us images of beauty and we consume them, internalise them and they become irrational yardsticks by which we measure each other. They sell us ourselves to consume. Even our anti-corporate sentiments are sold back to us. Our green sentiments are sold back to us by BP. And all too often, we gobble them up with relish. It should not be hard to see where ‘Revelation of the Daleks’ hooks into this.

September 15, 2012 @ 8:32 am

This is brilliant.

March 11, 2016 @ 12:45 am

Frozen and placed under Space Mountain, eh?

Sounds like Disney is our King In The Mountain.

And he’s not even a king! He’s an entertainer! He’s THE entertainer! Ah, but America doesn’t love kings anyway.