Sunburn Tatters (Book Three, Part 65: American Splendor)

Last War in Albion is produced with the support of my Patrons. My Patreon is currently in some trouble after a Patreon-mandated start from scratch to switch to per month billing, and is currently below the level of our monthly rent, which my family has historically relied on my Patreon to pay. If you enjoy my work, please consider supporting it.

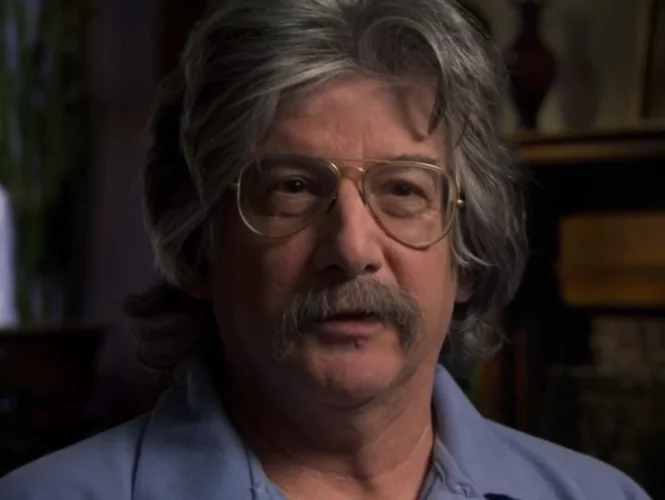

Previously in The Last War in Albion: Alan Moore contributed a story to Joyce Brabner’s Real War Stories project. Brabner got into comics, as she tells it, by appearing in one—specifically Harvey Pekar’s American Splendor.

Only the gutter margins where the strata peeled back into sunburn tatters gave away the lawyers of human time compressed below, ring markings on the long-felled cement tree-stump of the Boroughs. – Alan Moore, Jerusalem

American Splendor gradually evolved from the meandering anecdotal form into more long form and piercing accounts of Pekar and his life. Many of the stories were simply several page accounts of conversations Pekar had with various people in Cleveland, while others offered more piercing accounts of Pekar, his anxiety, stubbornness, and sense of himself. A story in American Splendor #3 entitled “Awakening to the Terror of a New Day,” for instance, starts with Pekar on the phone with his ex-wife, trying to get back together, only to be rebuffed, at which point he loses his temper at her and is castigated for it, concluding that “I shouldna lost my temper. That’s one reason chicks don’t dig me. They’re scared a’ me.” He lays down in bed, wakes up anxious, masturbates, and is left feeling hollow and empty inside. He takes a bath, reflecting on his job, and how he doesn’t want to get out of the tub. “Sometimes I wish I could freak out,” he thinks, “have a nervous breakdown, anything to get away from the same routine.” Instead he rises from the tub, gets dressed, grouching about how his clothes are tattered but how he doesn’t want to spend money on new ones because “what could be more ridiculous than fat slobs spendin’ a lot a’ money on clothes. They’re gonna look lousy anyway.” He has breakfast, leaves for work, and decides on the walk that he should take the civic service exam and look for a government job. The comic ends with him sitting at the bus stop, resolving that “I gotta take the days one at a time… make a plan an’ try t’ follow it out. I might be able t’ make it if I get my ass in gear. I’ll check out the gover’mint gig scene an’ think over where I stand with th’ chicks I know. Mybe I’m overlooking someone. T’day’s Thursday. Tomorra’s Firday. Saturday I c’n sleep late.” A final caption notes that “Man looks wherever he can for hope,” and the strip ends. It’s elliptical, willfully unsatisfying, but more than anything is simply a poignant reflection on working class life in Cleveland in the 1970s.

Pekar’s work drew a number of admirers, although the comic remained a niche operation that ran at a steady but sustainable loss.…