Was This Your Intended Statement? (Book Three, Part 63: Buster Brown at the Barricades)

Previously in Last War in Albion: To Moore’s delight, the V for Vendetta mask became an international symbol of anticapitalist protest on the back of the Occupy movement.

“All those logos on your raiment, brand-name badges of enslavement, drip-fed passive entertainment. Was this your intended statement?” -Alan Moore, “Mandrillfesto”

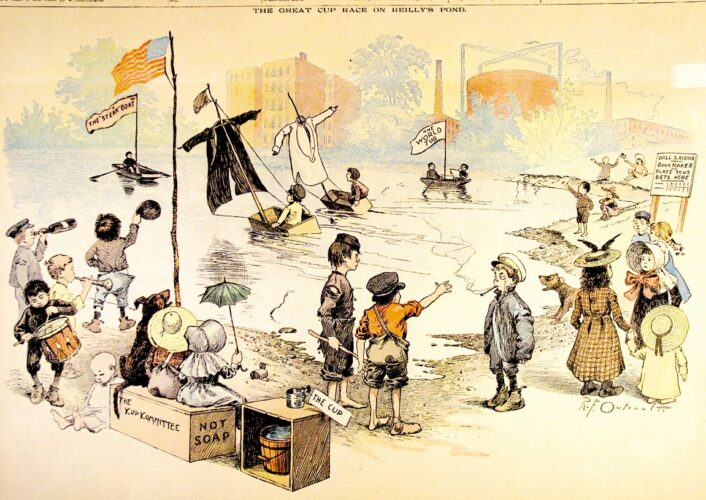

A month into the Zucotti Park encampment, indie filmmaker Matt Pizzolo, one of the distributors of the Grant Morrison: Talking With Gods documentary, announced a crowdfunded comics anthology to be called Occupy Comics, which was soon able to announce the participation of Alan Moore, who ended up contributing an essay to the project entitled “Buster Brown at the Barricades” that was serialized as the headline element of all three issues of the anthology once it came out in 2013. This was a lengthy work—over 21,000 words—in which Moore traced an alternate history of comics. Starting from the vogue among those inclined to mythologize the medium to trace its origins back to Egyptian times, Moore notes that “a very different, and perhaps more vital, reading of comic-book history becomes available if we simply turn over the stone blocks on which these stylised chronicles of Egypt’s kings or deities were carved. On the reverse of numerous stones that went to make the pyramids, inscribed on faces that were never meant to see the daylight, archaeologists have found what may well be the first anti-authoritarian and blasphemous satirical cartoons. These are depictions made, presumably, by bored and truculent stonemasons, of the same animal-headed gods to be found in the more conventional inscriptions, only here they’re shown as sitting around playing cards like some divine Egyptian poker school,” declaring this to be “the true historical precursor of the cartoon and the comic strip, the signifier of a grand tradition rooted in its healthy scepticism with regard to rulers, gods or institutions; a genuine art-form of the people, unrestricted by prevailing notions of acceptability and capable of giving voice to popular dissent, or even of becoming, in the right hands, a supremely powerful instrument for social change. It could even be said that, rather than such scurrilous and anti-social sentiments being a minor aberration in the otherwise sedate commercial history of comics, these expressions of dissatisfaction are the medium’s main purpose.”

Moore then proceeds to lay out this alternate history, looking at the relationship between comics and class in the early days of the medium by focusing on the treatments of poverty in Hogan’s Alley, the early days of Blondie, and strips like Mutt and Jeff, Bringing Up Father, and Li’l Abner before they settled into being a middle class concern. Throughout this, however, he notes the role of obscenity in the medium as well, with sections on Aubrey Beardsley’s “urge to shock and his desire to push his work beyond the boundaries of acceptability[, which] had very possibly no more of a refined conceptual basis than that of a teenager embellishing a garage door with an improbably enormous phallus, although executed with far greater delicacy and accomplishment” and on the way in which Tijuana Bibles were “puncturing the socio-sexual hypocrisy which held that sexual provocation was acceptable as long as the human activity which it was based upon was never mentioned or made otherwise explicit.”…