Guest Post: Introduction – A History of Video Game History

I am on extended hiatus from posting on Eruditorum Press, but I wanted to use my platform here to share this wonderful and exciting new project from my good friend Ben Knaak. Ben’s been a guest on Pex Lives and he and I have done a few audio recordings of our own together that some readers might remember. Anyone who’s interested in video game criticism and/or Marxist history and philosophy, which is to say statistically all of you, should really enjoy this new series.

I’ll be crossposting content here as it becomes available to me, but please do consider following Ben’s new blog and YouTube channel. That should be all from me.

Not a Country with an Army but an Army with a Country

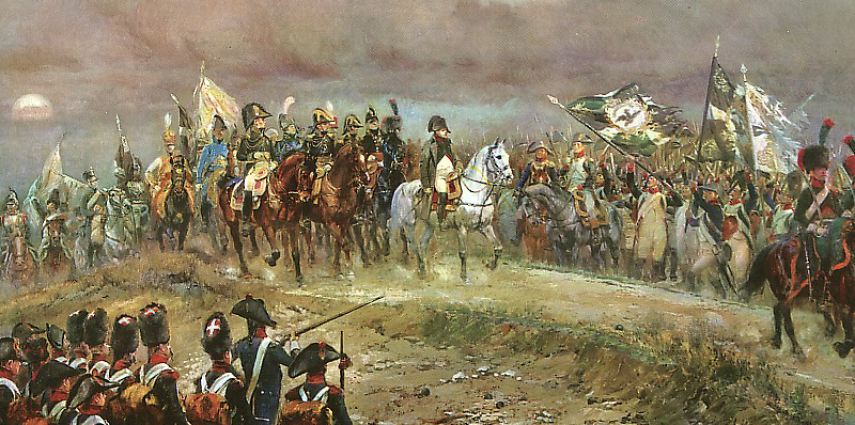

The story of Video Game History™ (as distinct from the history of video games, which is of course a different subject) does not, in fact, begin with Sid Meier. Nor even with Francis Tresham, designer of the original Civilization board game that introduced the infamous “tech tree” to the world. No, the long, slow gestation of Video Game History™ predates not only the existence of video games, but of Charles Babbage’s original difference engine. To the extent that any one Great White Man is responsible, the creation of Video Game History™ comes down to one of the greatest and whitest of them all: this bullshit is all Napoleon’s fault.

On October 14th, 1806, Napoleon’s armies crushed the Prussians at the Battles of Jena and Auerstedt, effectively ending Prussia’s involvement in the War of the Fourth Coalition. Their demoralized armies capitulated one by one, and less than two weeks later, Marshal Davout’s army entered Berlin. The Prussian aristocracy, which above all else tied its prestige to the success and discipline of its army, was stunned and humiliated.

They responded to this defeat with a complete and comprehensive overhaul of their military structure, bringing it more in line with the relatively more merit-based French system. Conscription was introduced, the officer corps was opened (for a time) to the middle class, a new war college was opened, and the highest leadership was reorganized into a new general staff, promotion to which would be based on merit. Emphasis was placed on the training of leadership, since they believed that this rather than the quality of the individual soldiers was what had won France the battle. The Prussian General Staff would convene to make plans for every possible contingency, devising first a broad objective to be accomplished which would be clear to all commanders involved. These plans would come to be called “Cases” – each military situation was like an academic problem to be solved. Or, if you like, a level to be beaten.

It was in this environment in the year 1812 that one of these Prussian officers, Lieutenant Georg Leopold von Reiswitz, compiled the original ruleset for a game that would come to be known simply as Kriegsspiel (literally “wargame”). It attracted little attention at first, but in the quiet postwar years, its popularity spread enormously among the officer class thanks to the promotional efforts of Chief of Staff Helmuth von Moltke.…