Guest Post: Introduction – A History of Video Game History

I am on extended hiatus from posting on Eruditorum Press, but I wanted to use my platform here to share this wonderful and exciting new project from my good friend Ben Knaak. Ben’s been a guest on Pex Lives and he and I have done a few audio recordings of our own together that some readers might remember. Anyone who’s interested in video game criticism and/or Marxist history and philosophy, which is to say statistically all of you, should really enjoy this new series.

I’ll be crossposting content here as it becomes available to me, but please do consider following Ben’s new blog and YouTube channel. That should be all from me.

Not a Country with an Army but an Army with a Country

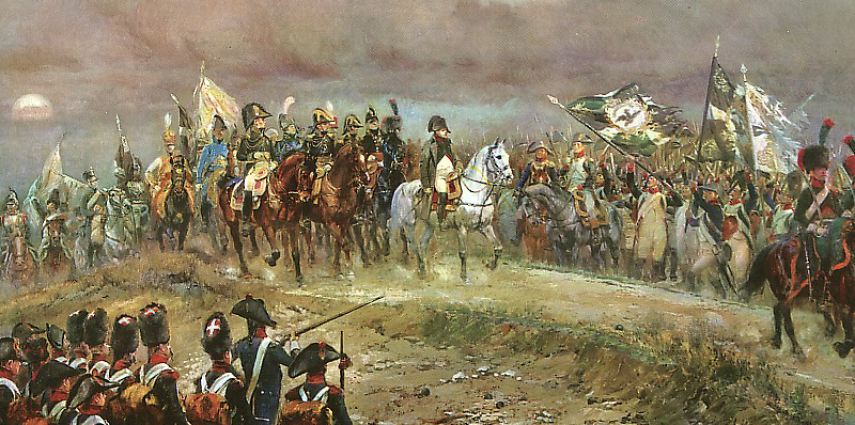

The story of Video Game History™ (as distinct from the history of video games, which is of course a different subject) does not, in fact, begin with Sid Meier. Nor even with Francis Tresham, designer of the original Civilization board game that introduced the infamous “tech tree” to the world. No, the long, slow gestation of Video Game History™ predates not only the existence of video games, but of Charles Babbage’s original difference engine. To the extent that any one Great White Man is responsible, the creation of Video Game History™ comes down to one of the greatest and whitest of them all: this bullshit is all Napoleon’s fault.

On October 14th, 1806, Napoleon’s armies crushed the Prussians at the Battles of Jena and Auerstedt, effectively ending Prussia’s involvement in the War of the Fourth Coalition. Their demoralized armies capitulated one by one, and less than two weeks later, Marshal Davout’s army entered Berlin. The Prussian aristocracy, which above all else tied its prestige to the success and discipline of its army, was stunned and humiliated.

They responded to this defeat with a complete and comprehensive overhaul of their military structure, bringing it more in line with the relatively more merit-based French system. Conscription was introduced, the officer corps was opened (for a time) to the middle class, a new war college was opened, and the highest leadership was reorganized into a new general staff, promotion to which would be based on merit. Emphasis was placed on the training of leadership, since they believed that this rather than the quality of the individual soldiers was what had won France the battle. The Prussian General Staff would convene to make plans for every possible contingency, devising first a broad objective to be accomplished which would be clear to all commanders involved. These plans would come to be called “Cases” – each military situation was like an academic problem to be solved. Or, if you like, a level to be beaten.

It was in this environment in the year 1812 that one of these Prussian officers, Lieutenant Georg Leopold von Reiswitz, compiled the original ruleset for a game that would come to be known simply as Kriegsspiel (literally “wargame”). It attracted little attention at first, but in the quiet postwar years, its popularity spread enormously among the officer class thanks to the promotional efforts of Chief of Staff Helmuth von Moltke. To an officer corps hungry both to plan for future battles and relitigate past defeats, Kriegsspiel was pure catnip.

Kriegsspiel, of course, was not the first game designed to emulate warfare, nor even the first Prussian game to do so. But after the many Prussian (and later German) victories of the 19th century, the popularity of Kriegsspiel began to spread outside Germany to militaries around the world. By the turn of the 20th century, civilian enthusiasts such as Fred T. Jane and even H.G. Wells were developing their own games inspired by Kriegsspiel. Even in the post-World War II boom period, when games like Tactics pioneered a new form of board wargaming for the mass market, the influence of the old Prussian training exercise remained.

Indeed, the mark of Kriegsspiel on tabletop gaming as a whole is not hard to spot. Much of what we now recognize was first introduced here: miniatures to represent units, an organized map grid to mark the field of play, dice rolls to determine probabilistic results, strict rules governing movement speed and combat capability, a simulation of the fog of war, and most notably an impartial third-party observer to determine the results of combat engagements, a direct progenitor to the gamemaster or umpire of today’s games. The line of influence is as direct as can be – Gary Gygax himself cut his teeth as a wargaming hobbyist. Kriegsspiel is the ghastly foundation on which the entirety of the roleplaying and strategy genres are built. Their very structure and approach to history and problem-solving are drawn from it and cannot be separated from it. Anyone who has ever played Risk, Dungeons & Dragons, Civilization, or Final Fantasy has been training to defeat Napoleon without realizing it.

A Genre Takes Shape

To this point I have used the ironically-trademarked term Video Game History™ without defining it. This is mostly because it’s one of those terms that is simultaneously hard-to-define but which everyone instinctively has a sense of what it means. We all know the standard critique of Civilization’s Tech Tree, after all. This sense of historical determinism is probably what you imagine when I use the phrase. But the particular form the historical telos takes is not important – only the fact that there is one.

Video Game History™, you see, consists of nothing more than the application of the logic of Prussian war exercises to Western historiography. To see this, we need look no further than virtually every historical and political strategy game ever made, every one of which shares the following things in common:

- They are each fundamentally about the military and/or political leader of one or more nations or armies.

- The game is meant to test the player’s capacity to, as leader, marshal the resources at their disposal to attain supremacy for their nation/army.

- This success or failure occurs in direct conflict and competition with other nations, whether through military means or peaceful ones.

- Success or failure is defined on the level of high command and high command only. National success is dependent entirely on the player.

Of course, the conception of history as a struggle between armies, nations, and their leaders’ ability to command them was not invented by Baron von Reiswitz in the year 1812. But it was in no small part through their Prussian lineage that strategy games inherited this attitude, which they retained as strategy wargames evolved into grand strategy games.

Grand strategy games first began to develop in the latter days of the tabletop wargaming boom of the 1970s and early 1980s, beginning with games such as Axis and Allies, which was designed in 1981 but republished by Milton Bradley in 1984, one year after Koei released their first computer grand strategy game, Nobunaga no Yabō (first in the series known in the West as Nobunaga’s Ambition).

The title of the latter should be enough to clue you into the fact that the approach hasn’t changed. The player assumes the role of one of the daimyo of Japan’s sengoku period, and your mission is to conquer all of the others to unite the country and become shogun. “Case Nihon,” the Prussians might call it. This time, however, you are placed in charge of the people and resources of the entirety of your holdings. In addition to raising and commanding armies, you must manage the economy and ensure that your peasants are happy, loyal, and well-fed. The larger the peasant base you have to work from, the larger and more effective your armies can be – a more underhanded player can even raise and train ninja. The goal is still conquest and the emphasis is still on leadership, but the logic has expanded to the idea of a total war – fought by entire populations, but commanded and decided by their noble leaders.

The original motivation behind the series even mirrors Prussian relitigation of Jena and Auerstedt. Kou Shibusawa, creator of the series, states that his inspiration was his long-held admiration for Nobunaga, and his belief that Japan may have become a stronger, more modern country far sooner had he lived long enough to become shogun. The notion of what might have happened if he had never risen to power and another daimyo had done so instead also intrigued him – surely Japanese history would be very different if any of these dozens of samurai possessed Nobunaga’s titular ambition. Setting aside the dubious truth value and Great Man-itude of such a statement, it is important to note that this viewpoint, as well as the game constructed around it, fundamentally views the driving force of history as a problem of command. If X general had made Y maneuver, Z country could have Won History. Grand strategy games are a marvelous place to play out this sort of alternate-history-as-command-exercise.

Koei would continue to make grand strategy games along these lines, the most popular of which are the Sangokushi series (Romance of the Three Kingdoms in its English release). Throughout the 80s and much of the early 90s they were nearly synonymous with the grand strategy genre, at least on the computer and console. The most notable of the other companies to make forays into the grand strategy was the American developer Strategic Simulations, better known for more traditional wargames like the Panzer General series. Their contributions to grand strategy were mostly set in World War II, with the exception of Colonial Conquest, set during the Scramble for Africa. As one would expect, these games hewed even more closely to the logic of the original Kriegsspiel.

Our Words Are Backed with Technological Determinism

While reasonably popular, the grand strategy genre still served what was primarily a niche market. At the same time Koei was making the Nobunaga’s Ambition series, other developers were taking the logic of tabletop wargaming in a more abstract direction which would ultimately prove to be more commercially successful (though this wasn’t the case at first). This group of broadly similar games form the loose genre known as 4X. The four X’s stand for their four most important elements of gameplay: eXplore (scout around the map), eXpand (acquire more territory), eXploit (gather and make use of resources at your disposal), and eXterminate (attack and defeat rival players).

Though nearly all players agree that 4X is a distinct genre, it is nonetheless difficult to say precisely where this genre diverges from grand strategy. The goals of a player of Europa Universalis are fundamentally similar to those of a player of Alpha Centauri. The primary difference lies in their aesthetic priorities – grand strategy tends to emphasize detail and historical or technical accuracy even at the expense of balance or accessibility, whereas 4X games are more willing to depart from reality for gameplay’s sake even if it makes the game more “gamey.” A country as powerful as, say, the Ottoman Empire in Europa Universalis IV would never make it into a historical 4X game, regardless of how powerful they were in real life. (This is not to say that 4X can’t be slavishly representationalist or that grand strategy never takes balance into account – it merely describes a preference).

The most notable example of the 4X genre is, of course, Civilization. Indeed, as hard a genre as 4X is to pin down, “games that are like Civilization” may be the best possible definition. For most, computer strategy begins here. For some, it ends here, too. This is not entirely unfair, either – the long shadow of Sid Meier continues to loom over the 4X genre, and virtually every other strategy genre as well. People who play and make strategy games aren’t thinking of a Prussian wargame almost nobody’s ever heard of, or even the tabletop games it inspired – they’re thinking of Civilization.

Its most influential innovation, of course, is the much-discussed Tech Tree – the most significant development in Video Game History™ since the Prince of Orange handed his sword to Prince Murat. It is at this point almost prosaic to point out that the presentation of technological, philosophical, and social development as a linear hierarchy of progressive upgrades presents a eurocentric view of history that is ahistorical even on its own terms. But from a gameplay perspective, the tech tree just works. It gives each game a natural rhythm – a feeling of a beginning, middle, and end – and a sense of epic historical scope. It provides multiple options for gaining particular qualitative advantages depending on the player’s situation and playstyle. This was the conscious design motivation for the invention of the tech tree. Not only is the tech tree a major factor in Civilization’s success, it seems hard to imagine how the strategy genre ever managed without it.

There’s a reason the tech tree fits the genre so well – like everything else in strategy gaming, it treats history as a problem of command. The knowledge produced by your civilization is a resource to be harnessed toward a particular end goal. It is up to you, the Great Leader of your nation to allocate those resources based on strategic needs. Do you take the military upgrade now, despite lacking the funds to turn your Pikemen to Musketmen? Or do you go for the economic upgrade?

Obviously no society, anywhere, has ever had its achievements and discoveries (to the extent that you can credit whole societies with such things) directed by a single person, one invention at a time. (Again, 4X games aren’t afraid to be “gamey” and non-representational with their history). This bears far more of a resemblance to a battlefield commander waiting for reinforcements or new equipment, and accounting for their resources. Should you take the oil fields now, or wait for the new tanks to arrive?

There is another sense in which the tech tree represents an unconscious return to the roots of the strategy genre. The framing of history as a deterministic techno-cultural hierarchy – a ladder of which every rung describes an inherently more valuable civilization – reflects the worldview of the time in which they lived. The 19th century marked the point at which capitalism and imperialism became a world-encompassing social narrative. Africa and Asia were carved up and subjugated by the European powers with the ostensible goal of bringing civilization to its people.

Here is where Kriegsspiel meets its other half, and Video Game History™ becomes complete. Field Marshal von Moltke has found his world to conquer. History is a linear and upward progression from barbarism to Enlightenment, from a village to an empire, from a stone hut to Alpha Centauri. If one is to be victorious over history, one must maneuver carefully and marshal all their nation’s forces to conquer it. The field is yours, Herr General – march over it, and all else who stand on it.

This is the story of Video Game History™, and with it the entire strategy genre. It cannot be separated from the ambitions of the German military aristocracy. Its vision of the 19th century is the primary story it tells.

But is that all that strategy games are capable of? Are there no other stories it can tell? It feels as though we’re forgetting something. Or someone.

Ludonarrative Marxism

The military aristocracy would not be the only Prussians who would have found sense in Video Game History™. A time traveling factory owner from Berlin would find it very intuitive. A hierarchical tech tree reflects his experience of material reality. The transition of Europe to an economy of machines and factories created unprecedented amounts of wealth, which led to the development of newer machines and more efficient factories, which led to more efficiency and created more wealth.

Until it didn’t. You see, there’s a funny thing that tends to happen to the rate of profit.

Yeah. There’s another historical narrative that came about around the same time, wasn’t there? Started with that German fellow with the big beard. I suspect many readers are familiar with him. Some of you may have even read some of the stuff he wrote about history. Probably a lot more of it than I have. But I’m committed to this project, so I guess I’ll have to take a stab at a crude summary.

Marx was the first to articulate what he referred to as the materialist conception of history. But much of the popular understanding of historical materialism derives from the later summaries written by Friedrich Engels. (Or even more accurately, the Bolshevik works which derived their understanding of it from Engels). This excerpt from his pamphlet Socialism: Utopian and Scientific serves as a decent summary:

The materialist conception of history starts from the proposition that the production of the means to support human life and, next to production, the exchange of things produced, is the basis of all social structure; that in every society that has appeared in history, the manner in which wealth is distributed and society divided into classes or orders is dependent upon what is produced, how it is produced, and how the products are exchanged. From this point of view, the final causes of all social changes and political revolutions are to be sought, not in men’s brains, not in men’s better insights into eternal truth and justice, but in changes in the modes of production and exchange. They are to be sought, not in the philosophy, but in the economics of each particular epoch.

Because humans must meet their material needs to survive, the first concern of any society will be the means by which the goods that meet them will be gathered, produced, and exchanged. Societies are therefore organized in accordance with these modes of production, and are divided into classes through the division of labor and ownership. (The better adherents will acknowledge that it is not the only reason social arrangements can exist, but it’s easy for some to forget).

One can therefore view history as a succession of modes of production, which arise not through the plans of great leaders but the action and reaction of the existing classes of the current mode of production. In Europe, for instance, the urban bourgeoisie of the Late Middle Ages and Early Modern period brought about the transition to industrial capitalism with ever-larger and more organized workshops and manufactories. As the producers of goods became more independent and the bonds of feudal society weakened, the state hastened their collapse by enclosing common lands, bringing a flood of former peasants from the fields to the mills and sweatshops. Their allegiance belonged not to a liege lord, but to the factory owners who extracted surplus value from their labor – the capitalists. As this arrangement continues, the exploited classes will become more aware of their role in capitalist society and acquire class consciousness. Then, when avenues for growth have been exhausted and the rate of profit dries up, when even the state-enforced stopgaps have failed, the organized working class will resolve the contradictions of capitalism by seizing the means of production and ushering in the next mode of production: socialism.

Or so the story goes.

Of course, Marxist historiography is open to criticism of its own, even from the left – particularly if one hews to the vulgar, reductionist version expounded by certain users of certain microblogging platforms. But as an alternative to Video Game History™, even the version of Marxism you get from anime avatars with flags in their profile names offers a crucial advantage. It gives us a different story – one which doesn’t completely center around leadership and Great Men, one which doesn’t measure the success of whole nations by a Great Man’s decisions, one where the strength of an empire can be acknowledged as detrimental to many of the people in it. But because it is a framework that makes predictions about the development of human societies which are at least to some extent deterministic, it’s a story which can still be fitted to the shape and pace of a strategy game.

So it should be no surprise that someone’s done it.

The Swedish Empire of Grand Strategy

Indeed, this isn’t even the first time I’ve covered the developers who did it. You may recall that last year Marsfelder and I recorded a two-hour Let’s Play/vodcast of the game Crusader Kings II, one of many grand strategy games created by the Swedish company Paradox Development Studio. Indeed, over the past decade and change, they have been nearly synonymous with the genre in the West, making series such as Europa Universalis and Hearts of Iron into some of the best selling grand strategy games ever. Over the course of two hours of discussion and gameplay, I argued that the primary appeal of Paradox games was their generative, organic storytelling. Their design is such that the gameplay itself creates masterfully compelling and detailed narratives with the feel and scope of centuries of history.

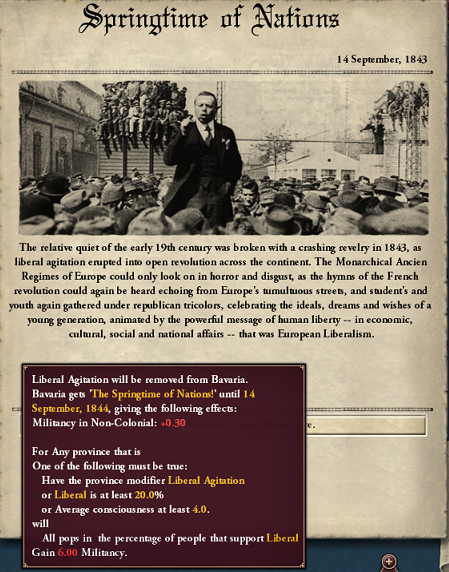

Naturally, this made them the ideal candidate to develop the series that made hardcore gamers fall in love with covert Marxist propaganda. So it was that in 2003, Paradox released Victoria: An Empire Under the Sun, to a raucous response of…complete and utter indifference. Seven years later, they tried again with Victoria II, which didn’t sell that well either. It did well enough, however, to receive two DLC expansions, and it retains a sizable cult following which only continues to grow as the player base for their other series expands.

Victoria II spans exactly one century of history, between the years 1836 and 1936. This is a much shorter time scale than Crusader Kings or Europa Universalis. But its years are long ones – it takes place during a century of social, political, and economic transformation, in a world alive with revolt. The world map you see at the beginning of the game will not resemble the one you see at the end. At the beginning, the old monarchies of Europe struggle to suppress the rise of liberalism and bourgeois nationalism. In the midgame, they struggle for continental and colonial dominance as socialism emerges. At the end, fascism lurks in the shadow of crises of overproduction and (usually) the aftermath of a world war. Elsewhere, non-western nations must adapt or be squashed under the bootheel of global imperialism.

What makes Victoria II unique, however, are the game mechanics that drive these changes. There is, as one would expect, a complex economic system that models the production and exchange of goods. But its true distinguishing game mechanic is the POP system, the elaborate means by which it models and characterizes assorted groups of people ranging in size from a few dozen to hundreds of thousands. All POPs in Victoria II are categorized by culture and, most importantly, by class. Farmer and Laborer POPs gather raw resources, which is sold on the market by the Aristocrat, who owns the land. Craftsman POPs work in factories, which are owned by Capitalists and managed by Clerks. Each POP has their own set of goods, that they need, both for basic subsistence and emotional well being. Most importantly, the POPs are dynamic – their size, wealth, political affiliation, militancy, and class consciousness changes in direct response to their material conditions.

Let me repeat that last one for the folks in the back: This game has a number to keep track of class consciousness.

This does not provide us with an entirely clean break from Prussian militarism. Nothing programmed in something called the Clausewitz engine ever could. In many instances, the historical materialism embedded in the game’s design merely provides an explanation for the imperialist behavior most players would be expected to engage in anyway. For instance, colonization allows for increased access to the raw materials required by Capitalist POPs, as well as providing them with new markets of exploited colonial Laborers and Farmers to which to sell their finished goods. But if it can’t completely break free of the baggage of its own genre, perhaps it can at least offer a self-critique. Or maybe even give the player a chance to create a better history.

But it wouldn’t be very materialist of me to simply tell you to take my word for it. Better we should test my assertions through direct demonstration.

Tewodros’s Ambition: Let’s Play Victoria II

Which brings me to the actual reason I wrote all of this in the first place. See, this entire essay is just an introduction to a Let’s Play I started planning back when I thought Paradox was about to announce Victoria III. (They, uh…did not).

This will be an informative Let’s Play, divided into 20-30 minute segments. I will try to introduce and explain Victoria II’s intimidating and complex mechanics, and also try to sprinkle in a few nuggets of historical insight as we go along.

I have chosen to play as Ethiopia, due mostly to its historical status as a center of resistance to imperialism, and due also to the challenge of prospering in a geopolitical climate which was historically hostile to attempts to industrialize “the periphery.” But there is a part of me that shares Kou Shibusawa’s fascination with particular moments in history – the day that upstart noble who united his nation was waylaid by the enemy, his friends having abandoned and betrayed him, and who, as the walls closed in, chose death instead of surrender. Of course, I’m talking about a different guy. But it’s the same question…what if?

What other stories could we have told about Africa, if this one hadn’t been interrupted?

August 23, 2018 @ 12:00 pm

I passed this on to my son, because he plays a lot of Hearts of Iron with the Kaiserreich mod so that he can play a syndicalist nation. As expected he was interested, and when he got to the line “this game has a number to keep track of class consciousness”, he laughed and said “now I want to rush out and get Victoria II!”

If nothing else, you’ve certainly got another viewer for your Let’s Play…

August 24, 2018 @ 11:09 am

The line from the original Kriegspiel to Avalon Hill and the 1960s miniatures that spun off D&D may not be as direct as all that — I’d say this bit needs more work. You can sew some particular pieces together, sure. One biographer of D&D painstakingly went from Chainmail to Tractics (which is now completely forgotten) and then back even a step or two farther, to miniatures systems that nobody has played for fifty years. But once you get back past WWII it starts to get very disconnected. Wells, for instance, seems to have designed his game in a vacuum, with no direct knowledge of what the Germans may have been up to.

Anyway. The medium of video games strongly encourages (though it does not require) the sort of supercentralized, god-king decision-maker model you’re talking about. But board games didn’t and don’t. You mention the original Civilization. Did you ever play it? Because the core engine of that game wasn’t the tech tree, and it wasn’t military expansion or resource competition either. It was the trading phase, where you haggled with six other players to take your random hand of miscellaneous cards and turn it into a standardized and highly profitable set of commodities. The key gameplay element was elegantly simple: sets of cards increased their value exponentially. So three cards of a particular commodity (gold, ivory, wheat, salt) were worth nine times more than one. If you could get get seven or eight of them and corner the market, boom: you were rich and could buy your way up the tech tree. Trade badly and you’d end up with a weak low-value hand and you’d only be able to buy cheap crap techs that nobody else wanted. This was an explicitly capitalist model, but it was also one that required a huge amount of face-to-face interactIon: diplomacy, cajoling, dealing, begging, threats.

(There was a complex subsystem involving screw cards and disasters, so players who were too overtly greedy invited nemesis.) And you had to play this part of the game.

For a more extreme example, consider classic Diplomacy. You control the fate of your empire! But your empire consists of just three units, and the ruleset is one step above checkers in complexity. No resources, no tech tree, nothing. And to accomplish anything — let alone to win — you have to interact vigorously with the other players; the game is designed that way. If you try to play Diplomacy like a 4X video game, you will die very quickly.

(And yet, in its relentlessly zero-sum nature, Diplomacy looks and feels more like a Kriegspiel dans le sens general than most Avalon Hill games ever did. Go figure.)

For a more recent example: Settlers of Catan. Explicitly colonialist (is that island really empty?) and capitalist. Yet you can’t ignore the other players; you must cooperate with them at least to trade cards, and the game encourages other forms of deal making (“I’ll let you use my wheat port if you’ll agree not to hit me with the Robber.”) Video games, as a medium just aren’t as well suited to this sort of thing.. (Or at least, not yet.) Most 4X games do include a diplomacy engine but it’s pretty much never at the center of the game; alliances in the Civ games, for instance, tend to be opportunistic and temporary until you’re strong enough that you can backstab your erstwhile chum. The diplomatic AI tends to feel like an afterthought, and strong players can often just blitz the whole world without much caring about diplomacy beyond the occasional tech exchange.

Incidentally, this has had a complex effect on boardgaming. Most obviously, I think it has driven the rise of cooperative board games in the last 15 years or so — without Civilization, you’d have no Pandemic. (And man, could you do a Marxist analysis of Pandemic: Legacy. I mean, this is a game about public health where, if you’re doing too well, your funding gets cut.) I think there are some other, more subtle effects, but this comment is probably already long enough.

Doug M.

August 24, 2018 @ 3:00 pm

I will readily admit to being far more familiar with strategy video games than I am with strategy board games, or indeed board games in general. Most of the time I spent playing board games more complex than, say, Trivial Pursuit, occurred years ago in college. Much of what inspired this portion of the post was reading Jon Peterson’s analysis of the wargaming roots of D&D in particular.

My primary interest here involves games as historiographical representation, and wargaming marked the first time in which games as we know them made an attempt to be truly representational of reality as opposed to something more abstract like chess. I don’t think it’s a coincidence that the modern alternate history genre first made its appearance in the post-Napoleonic years as well – it’s something of a “gamey” genre. But the history of gaming is an enormously broad subject, about which there is much I will freely admit that I don’t know.

Board games and tabletop games have, of course, developed in ways that have diverged substantially from computer and video games. Indeed, video games are in many respects much more limited, and one of the many ways this manifests is, as you have said, the relative lack of social play. This comes from both the lack of physical presence of other players and the comparative inflexibility of software compared to, uh…boardware. Modding a video game, even a game with scripting as simple as the Clausewitz engine allows, is nowhere near as easy as a GM making a judgment call or a party setting “house” rules.

With the exception of Hearts of Iron IV, whose streamlined nature makes it more suited for multiplayer than singleplayer, the primary focus of computer grand strategy is an atomistic single-player command experience. To be fair, much of my experience playing Paradox as a multiplayer game has involved a lot of negotiation and haggling via Discord. But much of this occurs in spite of the game’s mechanics rather than being integrated into them.

August 26, 2018 @ 11:33 am

I never think that the story of game history is interesting like this. Nice video.

September 4, 2018 @ 2:11 pm

This was a fascinating read. Thank you.

April 30, 2021 @ 2:09 pm

To be fair, much of my experience playing Paradox as a multiplayer game has involved a lot of negotiation and haggling via Discord.

November 15, 2024 @ 5:18 am

Thanks Omaar bhai for helping us in our difficult time.