The Chair Agenda

“The Chair Agenda” refers to the symbolic use of a Chair to indicate a process of Ascension. But this rather begs the question of what we mean by “ascension” and what, if anything, chairs have to do with it. I mean, it’s not like there’s anything about chairs in of themselves that would lead us to associate them with Ascension, is there?

“The Chair Agenda” refers to the symbolic use of a Chair to indicate a process of Ascension. But this rather begs the question of what we mean by “ascension” and what, if anything, chairs have to do with it. I mean, it’s not like there’s anything about chairs in of themselves that would lead us to associate them with Ascension, is there?

Which is to say, there’s nothing inherently metaphoric about this association. Unlike, say, the implicit underlying metaphor embedded in our very conception of “time-travel”: Time is conceived as a dimension of Space, and our experiences of moving through space are subsequently used to inform our relationship to time—we imagine traveling through time much like we move through space. Not that this is the only metaphor we have for understanding time. We also conceive of it as a Resource, as something to divide up, manage, and use, save, or waste.

Going back to chairs, though, there’s no obvious metaphor here. We sit in them. That’s it. We can’t even say that the form of a chair motivates an interpretation of Ascension, like an Eye in the middle of a forehead easily symbolizes “insight”—of thoughtfulness, creativity, intuition, the Divine, what have you.

So why Chairs? And what, pray, tell, is Ascension? Actually, it might be easier to start with how chairs, namely the body of evidence that employs the Chair in the context of ascension. For our purposes we’ll be focusing on Doctor Who, but this particular esoteric association is not limited to the favorite text of Eruditorum Press, as we’ll see. Thankfully, the first few examples will serve to highlight the association and lay bare the rather esoteric concept behind it.

The Library

We start with the Library, because it’s in the Library that Doctor Who first starts to make use of this symbolism relatively unambiguously. In the first episode, Silence in the Library, we get the first death of the story, that of Miss Evangelista (oooh, what a name!) She wanders into a reading room, where several chairs take the center stage, and one in particular looks almost like a throne, with upholstery in TARDIS blue. The camera pans behind the chair, behind some books… and then a scream. Our heroes come racing into the room, and discover a skeleton sitting in the high-backed chair.

We start with the Library, because it’s in the Library that Doctor Who first starts to make use of this symbolism relatively unambiguously. In the first episode, Silence in the Library, we get the first death of the story, that of Miss Evangelista (oooh, what a name!) She wanders into a reading room, where several chairs take the center stage, and one in particular looks almost like a throne, with upholstery in TARDIS blue. The camera pans behind the chair, behind some books… and then a scream. Our heroes come racing into the room, and discover a skeleton sitting in the high-backed chair.

We then get one of the most heartbreaking scenes of the story, if not the season. Miss Evangelista isn’t just dead… she’s “ghosting.” A technobabble explanation is given, but the important thing is that her consciousness has been freed from her body, and yet is still present. It is a sobering experience for the others, especially Donna, and eventually Evangelista moves on… and when she does, the camera itself rises high above the tableau, its point of view delineating a literal ascension.

But Evangelista isn’t quite dead. Instead she’s been uploaded to the Library’s mainframe, which puts her through a queer looking glass. Before she died, she was pretty, but stupid. After, her features are grossly distorted, but her intelligence has gone through the roof. And where once she was clad all in  white, now she wears black. But the “looking glass” doesn’t quite stop there. When Donna first wakes up in the virtual reality, she’s seen on a television screen, another sort of looking glass; the next shot presents Donna’s reflection in an actual mirror, which is propped up against a window. In this story, the Mirror is a portal to another world. And that Other world is governed by the rules of television.

white, now she wears black. But the “looking glass” doesn’t quite stop there. When Donna first wakes up in the virtual reality, she’s seen on a television screen, another sort of looking glass; the next shot presents Donna’s reflection in an actual mirror, which is propped up against a window. In this story, the Mirror is a portal to another world. And that Other world is governed by the rules of television.

Evangelista is the one to figure out the nature of this reality. She has become “aware”—and, funnily enough, not just aware that she’s in a virtual reality, but nearly to the point that she’s aware she’s a character on a television show, that the rules of the virtual reality are akin to television rules.

In so doing, the show itself demonstrates a modicum of self-consciousness, a heightened awareness that bespeaks the nature and experience of “ascension.” That this all happens in a Library, one that “goes on forever” as the little girl puts, as if it were the repository of all the knowledge and memories of the Universe, the Akashic Records, the Mind of the Goddess, I can’t even.

We now turn to the second ascension, namely River’s. Once again there’s a Chair involved. River will die there. But unlike Evangelista, River’s death is intentional, self-sacrificing. Hence the “crown of thorns” upon her head, and if you don’t think the Christ imagery itself is intentional, consider that River’s sacrifice triggers a mass resurrection (neatly, all the people “saved” return to the Library wearing Black, not unlike Miss Evangelista).

Hence the “crown of thorns” upon her head, and if you don’t think the Christ imagery itself is intentional, consider that River’s sacrifice triggers a mass resurrection (neatly, all the people “saved” return to the Library wearing Black, not unlike Miss Evangelista).

River’s ascension grants her narrative powers, in several respects. When the Doctor hovers over her diary, for example, now a part of the Library, he asks Donna if they should “peek at the end.” Which is funny, given that “ascension” involves ego-death, and as such provides “a peek at the end.” But any attempt to ascend for such a purpose is anything but ego-death; it is ego-serving. As such, the Doctor and Donna decline, as is only appropriate. It’s at this point that River’s voice now takes control of the audio on our TV sets. Her message is simple: Death is Inevitable. You can’t run forever. “Everybody knows that everybody dies,” she says, as an image of her empty Chair floats by, the back of it adorned with wings.

Our final images of River: dressed in white, almost glowing in a gauzy light, reunited with dear friends in a homecoming of her very own. Her voice-over continues. And at the very end, she looks at the camera, saying, “Sweet dreams, everyone,” and she turns out the light.

The Next Doctor

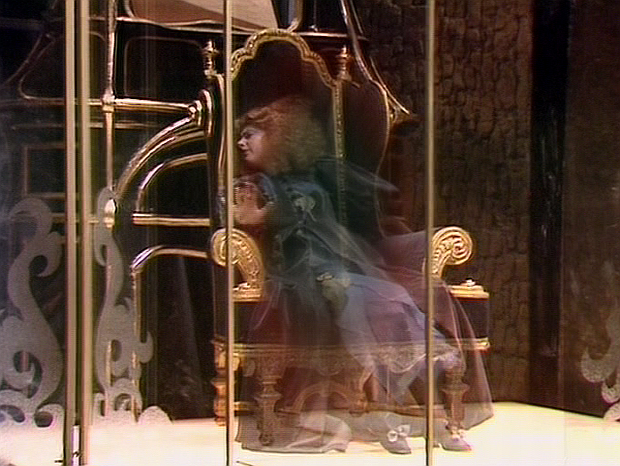

This next instance of Chair/Ascension symbolism in Doctor Who may well be the clearest. It’s also particularly interesting in that it features an antagonist. Here we have Mercy Hartigan, who’s in cahoots with the Cybermen in large part because of the deplorable treatment of women during the time of Victorian patriarchy; this is her revenge. But Mercy gets much more than she bargained for with this Ascension. And “ascension” is the perfect word here. It’s actually invoked by the text, twice:

CYBERLEADER: Plans for the Ascension demand a successful intervention. Is everything in position?

CYBERLEADER: If the Doctor is planning to intervene, then the Ascension will commence immediately.

Indeed, the text is littered with references to “rising”—Mercy even cracks a joke about it. Jackson Lake says it explicitly, “One day, I will ascend.” And of course, the Doctor uses the blue balloon to ascend into the air for his final confrontation with Mercy. The “ascension” referred to, however, isn’t just the rising of the CyberKing, but of the psychological process that happens when sitting in The Chair—again, the language is quite explicit:

HARTIGAN: Oh, that is magnificent. That is royalty, indeed. And that’s quite a throne. Oh, you will look resplendent.

CYBERLEADER: The chair you designate as “throne” is not intended for me. My function is to serve the CyberKing, not to become the CyberKing.

HARTIGAN: Then who sits there?

Mercy sits in the Chair. Not by choice, either; she does not want to become King. But she does become King. And the kind of “King” she becomes can be inferred from her self-description of the experience:

Mercy sits in the Chair. Not by choice, either; she does not want to become King. But she does become King. And the kind of “King” she becomes can be inferred from her self-description of the experience:

HARTIGAN: Behold such information! I can see the stars, the worlds beyond, the Vortex of Time itself, and the whole of infinity. Oh, but this is glorious!

CYBERLEADER: That is incorrect. Glorious is an emotional response.

HARTIGAN: Exactly. There is so much joy in this machine.

And so Mercy ascends, a union of Female and Male, taking control of all the Cybermen. But the use of Cybermen here ultimately subverts the very notion of Ascension. For the Cybermen are qlippothic husks that seek to avoid death at all costs, until nothing remains but their very egos, the exact opposite of the ego-death that confers true ascension points to.

Now, as I said before, the CyberKing isn’t the only one that ascends. The Doctor also ascends, in the big blue balloon. And his solution to Mercy’s subverted ascension is decidedly alchemical. Mercy begins and ends the story dressed in Red, indicative of the rubedo stage of the Great Work. But it’s obvious that she’s never passed through the previous stages of nigredo and albedo—she still retains all of her negative emotions, described by the CyberLeader as “anger and abuse and revenge.” Legitimate emotions, to be sure, given the patriarchal environment around her, but her response to patriarchy isn’t just to tear it down, but to step into those authoritarian structures herself. Her “great work,” in other words, is false, qlippothic. So all the Doctor has to do, really, when he ascends to meet her that final time, is to hold up a mirror to herself:

DOCTOR: I wasn’t trying to kill you. All I did was break the Cyber-connection, leaving your mind open. Open, I think, for the first time in far too many years. So you can see. Just look at yourself. Look at what you’ve done. I’m sorry, Miss Hartigan, but look at what you’ve become.

And indeed, finally aware that she’s become the thing she hates the most (a King) she has no recourse but to destroy herself. Ego death, indeed.

Once again, though, we have an interesting use of the Mirror. The Mirror (part of the albedo stage of the Great Work) in this instance isn’t a portal into an Other World, but into the Inner World. This is suggested in the scene where the Doctor discovers the “info-stamps” that triggered Jackson Lake’s amnesia. When the Doctor activates one of these devices, it shines into a mirror on the wall; a Cross stands within the shot.

Once again, though, we have an interesting use of the Mirror. The Mirror (part of the albedo stage of the Great Work) in this instance isn’t a portal into an Other World, but into the Inner World. This is suggested in the scene where the Doctor discovers the “info-stamps” that triggered Jackson Lake’s amnesia. When the Doctor activates one of these devices, it shines into a mirror on the wall; a Cross stands within the shot.

These particular metal devices have a history of London in them, but others have the history of the Doctor—again, the show demonstrates a self-consciousness to it.

JACKSON LAKE: I’ve seen one of these before. I was holding this device the night I lost my mind. The night I regenerated. The Cybermen, they made me change. My mind, my face, my whole self. And you were there. Who are you?

DOCTOR: A friend. I swear.

JACKSON LAKE: Then I beg you, John. Help me.

DOCTOR: Ah. Two words I never refuse.

Indeed, we might say that Jackson Lake himself has experienced an Ascension. His is one of Silver rather than Red, but we have all that we need—he’s lost his whole sense of Self. Ego death. And indeed, while Jackson also sought to ascend (hence the Balloon) he never wanted to exercise power over other people. He just wanted to look. And the fact that the “next Doctor” is named Lake, invoking Water—Nature’s Mirror—a man who believes he’s the Doctor because he saw “his” life flashing before his eyes, I still can’t even.

The Doctor, the Widow, and the Wardrobe

Which brings us to The Wardrobe. In this story, we get an early bit of foreshadowing regarding the Chair – the Doctor has made all the chairs in the sitting room mobile. Which is fun, cute, but the real fireworks are later, in the Androzani Forest. It’s particularly interesting that they’re called Androzani trees—in The Caves of Androzani, which didn’t have any trees at all, we got a substance that was practically a fountain of youth, and more importantly, we got a regeneration—a resurrection if you will.

And we need to point out that the show has also built up a particular resonance around the notion of Forests by the time Wardrobe aired. The Library, of course, was called a “Forest of the Dead,” but we also have to consider The Crash of the Byzantium, which featured a Forest that was decidedly “celestial” in that the trees were cyborgs that literally converted starlight into energy, not to mention becoming infested with Angels.

So now we come to this Androzani forest. Madge, another mature woman (like River and Mercy) literally ascends a giant tower, and within the tower is a massive wooden chair. She’s crowned, evoking both Mercy’s attempt to become “king” and the “crown of thorns” that River wore for her ascension. Sitting in the Chair, with the starlight of the forest pouring into her head, Madge describes a magnificent experience:

MADGE: That’s beautiful, isn’t it? See how it shines! Oh, this is marvelous. Oh, this is really quite wonderful.

DOCTOR: Madge? Are you all right? Talk to me. Madge, can you hear me?

MADGE: Yes, I can hear you. I’m perfectly fine, thank you.

DOCTOR: Fine? You’ve got a whole world inside your head.

MADGE: I know! It’s funny, isn’t it? One can’t imagine being a forest, then suddenly one can. How remarkable.

The Doctor says that she’s the one who’s got to fly everyone home. The “egg” at the top of the tower (symbolism, cough) ascends to the sky, and dives into the Time Vortex, the very Vortex through which the TARDIS travels to all of time and space. As Madge flies, she must remember, and we see her life flash before her eyes on the walls of the spacecraft. Her acceptance of her suffering (self-sacrifice of this sort is yet again a form of ego death) yields a resurrection, that of her husband. Okay, maybe that doesn’t make much sense, but it’s still thematically consistent.

The Wider Picture

We must note that the symbolism of the Chair does not begin nor end with Doctor Who. Indeed, it has had metaphorical implications for millennia; the association we are looking for isn’t rooted in metaphor, but in cultural symbolism.

The Ascension Chair has its basis in the “throne,” which is really just a fancy chair, but which stands metonymously for kings and queens, for ruling. Even in secular society devoid of royalty, we may still have a Chairwoman to preside over a board meetings, and of course in academia the Chair of a department is its ostensible leader.

And it’s this symbolism that is subsequently translated into religious experience. The Throne of God, for example, connotes a position of authority—and more importantly, understanding—over all creation. It is certainly the case in the Abrahamic religions. Revelation 4 describes the Throne as full of “lightnings, and voices, and thunders,” which sits in front of a sea of glass (a mirror, perhaps). The Quran states, “His throne extends over the heavens and the earth.” There is a school of Jewish mysticism referred to as Merkabah which concern accounts of various Ascensions (typically via some kind of chariot) to the heavenly Throne, oft described as being made of crystal gems.

This connotation of the Chair as a numinous object of the Divine is not restricted to Christendom. In Buddhism, for example, the “throne” corresponds to the Lotus of the Heart, implying a seat of the soul that transcends external dominion; indeed, the practice of “sitting” is at the heart of the most basic Buddhist ritual of meditation. We might also point to the “lap” as the point of origin in Goddess cosmogonies, the infinite womb of nature from which all creation springs.

Given such breadth of mythological significance, we should expect to see this symbolism occur in a variety of texts. And indeed we do. Take, for example, Alejandro Jodorowsky’s The Dance of Reality, a surreal musical drama about Jaime, a Chilean Communist who tries to assassinate the country’s right-wing dictator, only for his hands to become paralyzed when it’s time to do the deed. During his long journey back home, Jaime comes upon a carpenter who provides food and  shelter in exchange for the simple work of sanding down a room full of chairs. Jaime is cleaned up, rejuvenated, but his hands are still frozen into gnarled claws.

shelter in exchange for the simple work of sanding down a room full of chairs. Jaime is cleaned up, rejuvenated, but his hands are still frozen into gnarled claws.

They take the chairs to the carpenter’s church, and something almost magical happens. The priest gives a rousing sermon, and all the parishioners raise their chairs on high in celebration. But when the carpenter dies in that moment, they do not weep and mourn; no, they praise the carpenter by standing on the chairs in glorious revelry. While this does not lead to ascension for Jaime (indeed, he simply ends up leaving at this point, and only becomes healed when he deals with his family issues), it certainly points to a religious connotation with chairs in a text normally outside the purview of Eruditorum Press.

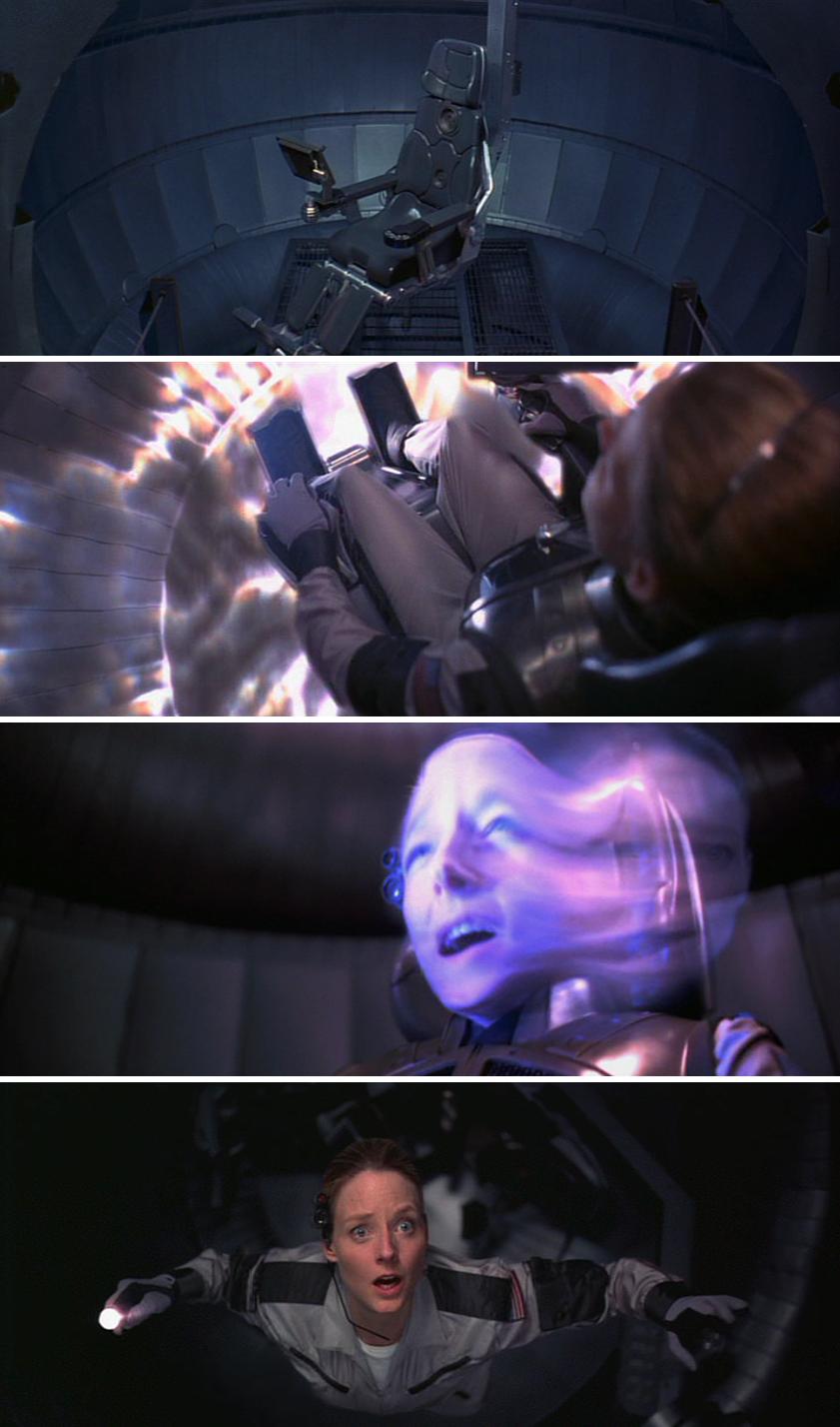

But now we’re going to lean into that purview—we have a wealth of examples to choose from within popular science fiction—by turning to the movie Contact, which is about the intersection of science and faith. Ellie Arroway (what a name!) is  the scientist who will be the first interdimensional space traveler. Her ship is a giant silver ball—reminiscent of a Sontaran spaceship—suspended in the skeleton of a dodecahedron, the interior of which is empty except for a Chair hanging from the ceiling.

the scientist who will be the first interdimensional space traveler. Her ship is a giant silver ball—reminiscent of a Sontaran spaceship—suspended in the skeleton of a dodecahedron, the interior of which is empty except for a Chair hanging from the ceiling.

The ship is to be dropped into a massive electromagnetic field generated by what appears to be a giant gyroscope. As the field builds up, from Ellie’s perspective the ship becomes translucent, but this is not apparent to outside observers. The Chair begins to shake. And when the arm holding the ship finally lets go, Ellie has a transcendent experience, traveling through wormholes into the heavens. At one point she seems to be having an out-of-body experience—at least, this is what the imagery suggests.

Eventually she realizes she no longer needs the Chair, and upon releasing herself from it she floats in mid-air; this is her Ascension. She ends up on a beach, perhaps that of an Island… where she meets an alien intelligence that’s taken the form of her dead Father. But upon her return, no one can believe her. The external monitoring equipment indicates she never went anywhere, and her video feed yields only static (cough). Which is to say, this was an internal experience, but one that’s implied to have really happened.

Other, more recent SF properties have likewise employed the Chair to similar effect. LOST, for example, gives us Desmond Hume tied to a chair inside a cabin, subjected to a massive amount of electromagnetism, and having an experience of the Afterlife. John Locke, a paraplegic, rises from his wheelchair upon reaching the Island. A supernatural event in Jacob’s Cabin centers around an empty chair. And even the Others use a Chair, a la A Clockwork Orange, as a tool for religious brainwashing.

A show that features the Chair most centrally is Dollhouse. In Dollhouse, the Chair is a place where the mind can be downloaded, and which can upload new minds into the host. The hero of the show, Echo, ends up being able to “save” every mind she’s been programmed with, such that she becomes truly polyphrenic. In the Season One finale, she is called “Omega” by the antagonist Alpha, who also had  experienced polyphrenicism via the Chair—the phrase “Alpha and Omega,” of course, points back to religious terminology. The Chair is a place where people can escape death, and indeed it can confer a kind of resurrection. In the episode Haunted, the mind of a dead woman is uploaded into Echo. The woman declines to run off with her new body, accepting that her death must be final. In her final moment, she asks Adelle, “Will my life flash before my eyes?” Adelle answers, just before the Chair activates, “Every single moment.”

experienced polyphrenicism via the Chair—the phrase “Alpha and Omega,” of course, points back to religious terminology. The Chair is a place where people can escape death, and indeed it can confer a kind of resurrection. In the episode Haunted, the mind of a dead woman is uploaded into Echo. The woman declines to run off with her new body, accepting that her death must be final. In her final moment, she asks Adelle, “Will my life flash before my eyes?” Adelle answers, just before the Chair activates, “Every single moment.”

In Stargate Universe, the ship Destiny has a Chair built by the Ancients, which has access to “repositories of knowledge,” which sounds suspiciously like The Library in Doctor Who. The Chair has a Neural Interface through which knowledge can be downloaded directly into the user’s mind. Given that the Chair could leave one dead or catatonic, the Destiny’s scientists modify it to only target the subconscious portion of the mind. One crewmember, Rush, uses the Chair and experiences “lucid dreaming,” while another, Franklin, is able to activate Destiny’s Faster-Than-Light drives, whereupon he vanishes. Such events, especially taken metaphorically, point to our mystical associations.

Finally, in the Luc Besson movie Lucy, Scarlett Johansson’s titular character progresses towards her own ascension (sped up by some miraculous crystal-gem drug) which culminates in a scene where she travels the Universe—and indeed through time—in a perfectly ordinary office chair, a voyage that suggests she’s influenced human evolution itself, before she finally disappears with the implication that she has become a transcendent Goddess.

Finally, in the Luc Besson movie Lucy, Scarlett Johansson’s titular character progresses towards her own ascension (sped up by some miraculous crystal-gem drug) which culminates in a scene where she travels the Universe—and indeed through time—in a perfectly ordinary office chair, a voyage that suggests she’s influenced human evolution itself, before she finally disappears with the implication that she has become a transcendent Goddess.

Back to Doctor Who

But it’s in Doctor Who that we get an incredible variety of interesting Chair representations, which is afforded in no small part by the show’s ability (indeed, its mandate) to do something different every week. Looking at just a few instances, we can build on the aforementioned connotations, or even use this context to ponder new interpretations of the scenes in question.

The Pandorica, for example, has a lovely Chair in the middle of that cube, a cube adorned with Circle in the Square motifs, a Masonic symbol for the union of the Divine and the Material Body. All kinds of interesting things happen with this Chair. For one, the Doctor is able to reboot the entire Universe from it, piloting a “perfect memory” of the Cosmos into an exploding TARDIS that currently reaches every corner in time and space. Talk about “throne of God”-type stuff. Which is coupled at the end with his life flashing before his eyes.

The Pandorica, for example, has a lovely Chair in the middle of that cube, a cube adorned with Circle in the Square motifs, a Masonic symbol for the union of the Divine and the Material Body. All kinds of interesting things happen with this Chair. For one, the Doctor is able to reboot the entire Universe from it, piloting a “perfect memory” of the Cosmos into an exploding TARDIS that currently reaches every corner in time and space. Talk about “throne of God”-type stuff. Which is coupled at the end with his life flashing before his eyes.

There’s another occupant of that Chair, however: Amelia Pond. She is put into the chair in order to effect her resurrection, literally bringing her back from the Dead. And given that the Pandorica can “save” memories, it turns out that so too can Amy, who brings her family back from the dead as well. Not to mention the Doctor, at her wedding, which can easily stand as a metaphor for the “union” of the Divine in the Material, or any other pair of opposites.

In Asylum of the Daleks we get a very different sort of ascension. The Chair in question here is one of Oswin Oswald’s devising. Interestingly, the physical prop they used was the same chair that the Doctor’s daughter Jenny sat in after her resurrection back in Series Four. Oswin’s chair is located in the “mind’s eye” of a Dalek, a set that’s designed to look like an Eye. At the end of the story she ends up sacrificing herself so the Doctor and the Ponds can “ascend” back up to the TARDIS in the Dalek spaceship high above the planet. In her final scene, sitting her Chair, she breaks the 4th Wall by looking into the camera and saying to “remember” her.

In Asylum of the Daleks we get a very different sort of ascension. The Chair in question here is one of Oswin Oswald’s devising. Interestingly, the physical prop they used was the same chair that the Doctor’s daughter Jenny sat in after her resurrection back in Series Four. Oswin’s chair is located in the “mind’s eye” of a Dalek, a set that’s designed to look like an Eye. At the end of the story she ends up sacrificing herself so the Doctor and the Ponds can “ascend” back up to the TARDIS in the Dalek spaceship high above the planet. In her final scene, sitting her Chair, she breaks the 4th Wall by looking into the camera and saying to “remember” her.

Dinosaurs on a Spaceship has a more Campbellian ascension to it—this time the Chair is mirrored or twinned, so that Rory and his father Brian can pilot the Silurian Ark (omg, the religious symbolism) away from danger. I say this is Campbellian because it represents the atonement between father and son, or as Campbell puts it, the At-One-Ment between father and son, for after this Rory and Brian are much better able to understand each other; indeed, Brian becomes like his son through traveling while Rory  becomes like his father by recognizing that a lightbulb isn’t at fault, but rather its fixture. Other parallels included twinned injuries to their shoulders, and a habit of keeping their pockets full of tools—Rory’s with nursing supplies, Brian’s with a trowel—a symbol of “connecting” or “binding” through love according to Freemasonry, itself a moral system veiled in allegory and steeped in symbolism. Taking Father and Son as symbols for the Divine and Material Creation, their subsequent union is perfectly in line with what we’ve talked about so far.

becomes like his father by recognizing that a lightbulb isn’t at fault, but rather its fixture. Other parallels included twinned injuries to their shoulders, and a habit of keeping their pockets full of tools—Rory’s with nursing supplies, Brian’s with a trowel—a symbol of “connecting” or “binding” through love according to Freemasonry, itself a moral system veiled in allegory and steeped in symbolism. Taking Father and Son as symbols for the Divine and Material Creation, their subsequent union is perfectly in line with what we’ve talked about so far.

One of the most blatant examples of The Chair Agenda comes in The Crimson Horror, an episode resplendent with occult references, including explicit mention of The Great Work, the quoting of William Blake, and an invocation to a Hermetic organization: The Golden Dawn. In Crimson Horror we have a chair used to break Clara free from the bell jar that would stultify her in Victorian aesthetics, a chair used to smash the villain’s evil machine, and even dialogue where the Doctor proclaims “Chairs are useful” while holding a chair behind his head, effectively creating a chair halo.

The Caretaker features a circle of Chairs upon which the Doctor has placed “chronodynes” to create a time vortex that will propel the Skovox Blitzer into the far future, but this episode is really about Danny’s  first ascension: after he discovers what Clara’s been up to, who the Doctor is, the nature of the TARDIS, and a wristwatch that makes him invisible (a holy ghost, in other words), he leaps in the air over the monster to save the day.

first ascension: after he discovers what Clara’s been up to, who the Doctor is, the nature of the TARDIS, and a wristwatch that makes him invisible (a holy ghost, in other words), he leaps in the air over the monster to save the day.

This story has an interesting mirror—not only is there a circle of fire in the circle of chairs, but there’s also a circle of fire in a squarish stack of chairs. And in hindsight this is particularly interesting as a foreshadowing of Danny’s role in the season finale. In Dark Water we find tombs filled with water… and empty chairs, our symbol of ascension. Within the chairs, however, are Cybermen. Danny becomes a Cyberman, and saves the day by getting them all to ascend up into the sky in a fiery blaze.

Finally, just to go back to a much earlier time, there’s The Keeper of Traken. The Keeper of Traken sits upon a magic chair that can flit through space on a whim. It is from the Chair that the Keeper has access to “The Source,” which grants godlike powers. When the Keeper dies, a new candidate must take the Chair. It is first taken by Kassia, but her motives are not pure, and so she is tricked by the Master, who substitutes his “Melkur” into the seat of power. Of course our heroes defeat him, and the new Keeper ends up being Luvic, an unassuming man who never wanted the position in the first place. Indeed, the only candidate worthy of such power is the one who doesn’t want it. But it’s interesting, I think, that the story itself makes the Chair almost into an object of horror, as if this were actually a terrible fate.

Well, that’s what Doctor Who is for, isn’t it?

October 6, 2015 @ 10:49 am

Sorry this went up late — forgot to press “save” after I toggled the Draft/Publish button.

October 6, 2015 @ 11:50 am

I’m almost tempted to ask about Davros’ chair, but I imagine it was covered in your section about The Next Doctor – “For the Cybermen are qlippothic husks that seek to avoid death at all costs, until nothing remains but their very egos, the exact opposite of the ego-death that confers true ascension points to.”

Davros to a T.

October 6, 2015 @ 1:13 pm

And here I thought the Chair Agenda had something to do with the Doom Patrol story “The Empire of Chairs” (not in the least because the main character’s name in that story is Jane).

In any case, great entry. Will you be covering more esoteric/alchemical motifs in this way?

October 6, 2015 @ 2:24 pm

Absolutely!

October 7, 2015 @ 10:22 am

No mention of the Use of Weapons? A certain white chair features heavily in that.

Not much to do with ascension though I’ll grant you.

October 7, 2015 @ 10:35 am

I have told Jane she should read Use of Weapons before due to it having one of the most memorable chairs in science fiction.

October 7, 2015 @ 5:12 pm

Fascinating stuff – another that springs to mind is the throne that Barbara sat on in The Aztecs, becoming a goddess in the process.

October 11, 2015 @ 9:45 pm

Haven’t had time to read all of this post yet, but it immediately brought to mind this awesome video essay:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=FfGKNJ4mldE

Tony’s series of videos on his channel Every Frame a Painting are generally very worth checking out.