The Tour of Life

Tour of Life

Hammersmith Odeon

Manchester Apollo

Let It Be

I Don’t Remember

Nationwide documentary

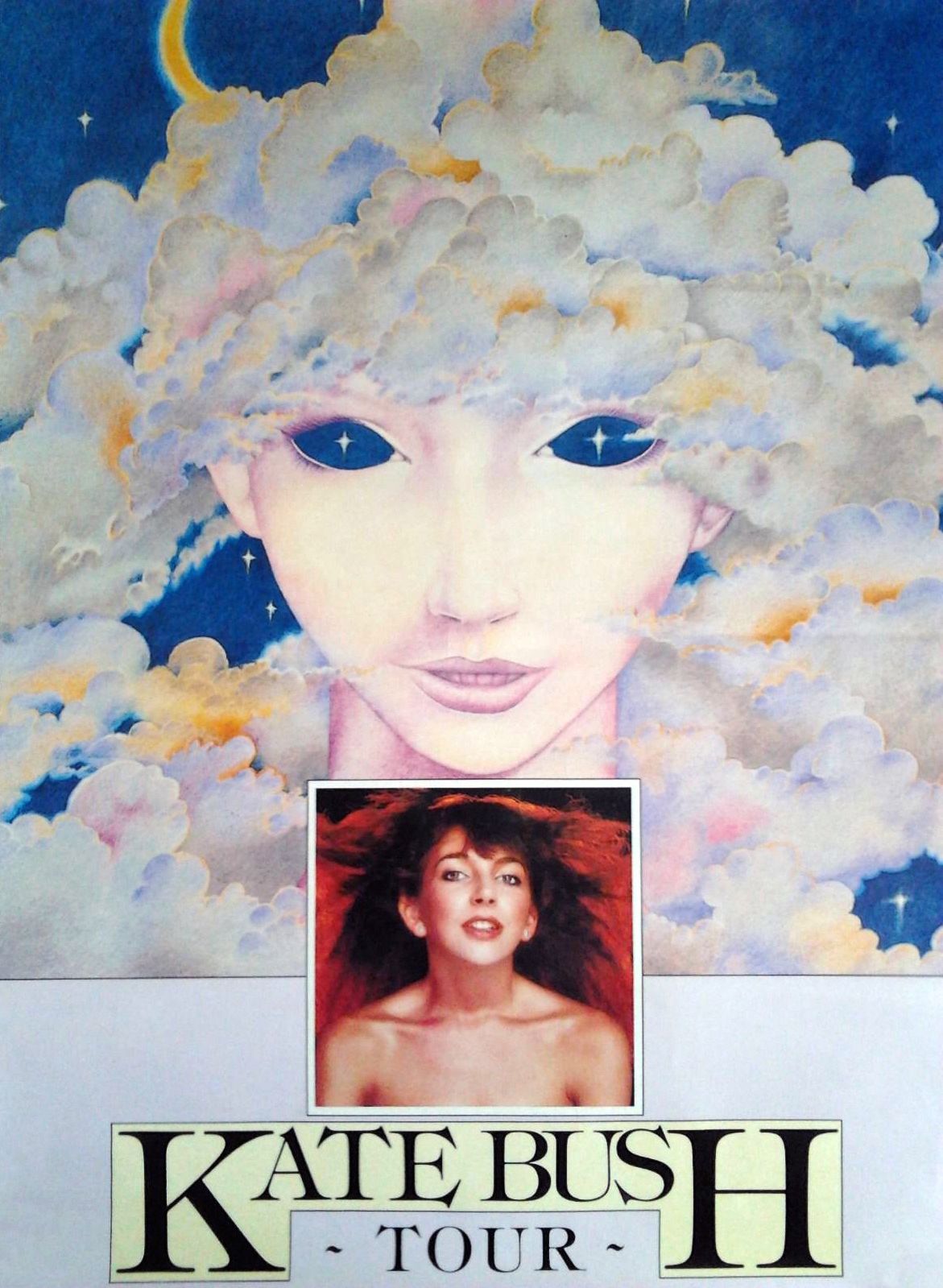

The touring career of Kate Bush consists of 29 shows across 6 countries in roughly 6 weeks, with performances of 2 existing albums and a burgeoning third. Bush’s singular tour defines her career as much as “Wuthering Heights,” Hounds of Love, and her 12-year moratorium on new albums between The Red Shoes and Aerial. The difference between that music, that gap, and the tour, however, is accessibility. You can listen to Bush’s music pretty much whenever provided you have the physical media, or a steady Internet connection. The Tour of Life is Bush’s only tour — if you wanted to see her do a full concert outside of the UK, you could only have done so in April or May 1979. Sparseness is a key ingredient of Bush’s career, one that perhaps makes her especially suitable for a project like this blog. She builds her work piece by piece, letting it be an accumulation of important steps.

Planning for Bush’s tour (known then and during its existence just as the Kate Bush Tour) began at the end of December 1978 with a brainstorming session involving Bush and set designer David Jackson at EMI’s headquarters. Further preliminary meetings were held at East Wickham Farm in January, and shortly afterwards Bush was meeting wardrobe consultant Lisa Hayes. Rehearsals then began in earnest: Bush spent mornings at The Place performance center in Euston, preparing the tour’s dance routines with choreographer Anthony Van Laast (now of Mamma Mia! and Harry Potter fame) and dancers Stewart Avon Arnold and Gary Hurst. These sessions were as collaborative as they were instructive: Bush had worked with Van Laast before, as he’d appeared in the “Hammer Horror” music video as her masked dancing partner. They spent the mornings designing routines for the show, informed by Van Laast’s seasoned dancing skill and Bush’s mime training. It was a positive union: the resulting concerts have notable dancing which is inseparable from the songs it’s set to. As Bush had to both sing and dance onstage, she and Van Laast worked out choreography that would both work as dance and allow her to sing without losing her breath. The minimalism of “Moving” and Bush’s all-limb gesturing during it is one such careful work of planning, as is her most frenetic gun-happiness during the extended bridge of “James and the Cold Gun,” where she doesn’t sing.

Rehearsals for the tour’s music were staged initially at Wood Wharf Studios in Greenwich, before moving to Surrey’s eminent Shepperton Studios in March. The shows were precisely outlined, retaining the ideas of The Kick Inside and Lionheart while developing them further onstage. Lionheart is at its core a work of musical theater, and its stage incarnation helped it to be the best version of itself. Out was the ill-paced sequencing of the album, supplanted with a solid theatrical structure. Bush also had a different lineup of musicians than her two albums so far: she’d begun sneaking the KT Bush Band into the studio by including them on “Wow” and “Kashka from Baghdad,” but a proper reunion of the old touring group was mostly in swing onstage. It wasn’t the exact same band (drummers Charlie Morgan and Vic King declined to return), but the quartet of Bush, bassist (and her partner) Del Palmer, guitarist and bandleader Brian Bath, and stalwart polymath Paddy Bush were playing music together again. Preston Heyman, Bush’s best drummer to date, joined the group and brought a percussive explosiveness to the concerts that the albums lacked (“when he hit the cymbal Kate used to blink,” said Brian Bath). Keyboardist Ben Barson, saxophonist and pianist Kevin McAlea, and guitarist Alan Murphy were the other new additions to the group, assuring that the shows would sound as lush as Bush’s albums.

Hype around the tour was extensive, and Bush took advantage of it: she racked up a long list of interviews around the time, gave members of her burgeoning fan club free tickets, and posed for a picture with Prime Minister James Callaghan. The Winter of Discontent had passed, and Bush was a hot ticket to popularity for someone like Callaghan (the ploy didn’t work — Callaghan’s Labour government collapsed in favor of Margaret Thatcher’s Conservative one). The press was all over her, if largely in the wrong ways — the Daily Mail made a fuss about her, describing her as “sensuous” (a posh synonym for “fuckable”) and vocally wondering if a husband was in her immediate plans. The Sun didn’t behave any better with their descriptions of Bush as “a seductive siren with a deadly aim,” as if sirens are sharpshooters. One of my favorite bits of golden journalism around Bush comes the Daily Star, which suggests her cats Zoodle and Pyewacket were “past lovers whom she [had] cast a spell on.” It’s not everyday a journalist tells you Kate Bush fucked her cats, but such is the beauty of tabloids. A new woman was on the scene for gross male journalists to objectify, and she was about to prove them to be inept tools.

Every tour performance began with “Moving.” Whale sounds were played for several seconds, as they were on The Kick Inside, while a transparent blue curtain cordoned off those onstage from the audience, with only a bright light in the center of the stage and the silhouette of Bush completely visible through it. Then came the vocal and the piano: “moving stranger, does it really matter/as long as you’re not afraid to feel?” called Bush to her audience as the curtain was pulled back. Her dance, made up of open arms and gestures aimed at the outline of her body, was an invitation to the audience to collaborate and be part of her music. According to every recording of these concerts, it was a steady introduction: when the first number ended, the audience cheered loudly. “The show went well and the audience was wildly appreciative,” said Lisa Bradley in the Kate Bush newsletter, “it was unfortunate that we rarely had a chance to see it as the merchandise stand had to be looked after all the time.”

Every night of the show got stark raving reviews from the British press. Mike Davies of Melody Maker admitted going to see Bush “more as a pilgrim than a critic,” John Coldstream of the Daily Telegraph praised her “balance between the vivid and the simple,” and former Bush naysayer Sandy Robertson of Sounds announced she had “seen the light.” There were a couple reviews from more negative quarters, mostly notably by Charles Shaar Murray in NME, who opined that “her songwriting hints that it means more than it says and in fact it means less” and “her shrill self-satisfied whine is unmistakable.” One could smugly grin at Murray for panning a critically praised and influential tour in 1979, but why do that when he invented every sexist whinge about Lauren Mayberry more than three decades early? It’s a break from the orthodoxy of Bush’s tour reviews, and thus in keeping with Bush’s ethos.

An oft-commented on aspect of Bush’s shows in reviews was its synthesis of theater and rock. This is a glib and useless description are there were many “extravaganzas” in rock music at the time, but even among them the Tour of Life broke rank. Bush had more planned for her debut concerts than simply playing her new album — she was producing a stage show, a colorful spectacle with extensive costuming, mime routines, dancers, act breaks, poetry, and elaborate set design. “I think the most important thing about choosing the songs is that the whole show will be sustained,” said Bush later. “…the songs must adapt well visually: a show is visual as well as audial, so there must hopefully be a good blend of the two.” As per usual, Bush’s way of proving herself was unorthodox. While there were other especially theatrical rock acts performing at the time (glam was the world’s loudest costume drama, and prog acts like Genesis and Pink Floyd thrived on massive setpieces, and disco and ABBA were more theatrical than they were credited for), they were mostly playing their songs live with different arrangements and more props. Bush was staging a long play, with dance acts, characters, and spoken word segments. The concerts were made by small flourishes: “The Kick Inside” got a spoken prelude by John Carder Bush with a foreboding call-and-response (Kate hauntingly shouts “two in one coffin!”), “Saxophone Song” has a saxophonist projected onto the stage, and mime Simon Drake appears decked out in white make-up as Charlie Daniels’ devil channeled through Iggy Pop. A classic component of the shows is, bizarrely, from the “Room for the Life” performances, in which Bush is rolled around in a velvet cylindrical egg (get it? It’s a uterus). She eventually departs the egg and frolics with her band during the song’s outro, giving way to Bush’s greatest performance ever as she enthusiastically calls “a-woom-pa-woom-pa-woom-pa-woom-pa-woom-pa!”, elevating the worst song on her debut album to a highlight of her career.

Salvaging “Room for the Life” isn’t Bush’s greatest feat at this time, however. It was unprecedented for women artists to undertake projects of this scale at the time. Bush was hopping into a steadfastly rockist tradition and putting a feminine spin on it. We have Björk, Laurie Anderson, and Florence + the Machine because of shows like this. You know those weird headset mics artists use sometimes to stay handsfree while performing? Bush was the first singer ever to use those, and she did it here. This is pretty much the Seventies equivalent of Zoo TV and The Wall Tour, and a woman got there first.

Rather than feeding on nostalgia (a hard feat for a recent artist to pull off), Bush used her existing work as a diving board for her live shows. For all the strengths of The Kick Inside and Lionheart as albums, the live versions of a few of their songs are superior: the revamped band bring the songs a power the original recordings sometimes lacked. “Coffee Homeground” sounds tighter, and even the unimpeachable “Wuthering Heights” improves slightly when Alan Murphy improvises bits of the track’s guitar solo. There are plenty of odd musical choices throughout the shows: there’s an electronica-inflected rendition of Satie’s Gymnopedies leading into “Feel It,” and “James and the Cold Gun” becomes the 10-minute prog jam its album counterpart was itching to be. This doesn’t suggest that Bush has been constrained by the studio — in fact, it’s likely she works better outside of the traditional rock band format. But in many ways she’s liberated by her chance to do musical theater, showing off what her songs look like and pushing some aspects of their sound a bit further.

In theory Bush was doing the Lionheart Tour, as it was her most recent album. Yet in practice, it was equally the Kick Inside Tour. All the songs from both albums were performed barring “Oh To Be In Love” (perhaps justifiably — it’s the Bush album track which most feels like a holdover from the Phoenix years), plus a couple of new songs called “Violin” and “Egypt,” the latter of which we’ll return to next week. It’s a well-organized setlist, as Kick and Lionheart are both preoccupied with the sort of adolescent world-storming the tour is. Bush’s concert setlists show off this interplay of albums well: Act One is constructed around the lighter songs of The Kick Inside like “Them Heavy People” and “L’Amour Looks Something Like You” with the two new songs, while Act Two centers the anxiety-ridden bulk of Lionheart plus “Strange Phenomena,” and Act Three provides the show with a theatrical climax of “Coffee Homeground” and “Kite” before the encore of “Oh England My Lionheart,” and finally “Wuthering Heights.” Setlists can be unruly things: while touring for albums, you’ll want to intersperse the newer material with the hits. Bush keeps this in mind while also remembering she’s doing a stage show with act breaks and thematic resonances. It’s a strong act, one that’s bolstered by its setlist.

The artistic precision of the concert belies what occurred behind the scenes. Bush was exhausted by the shows and the preparation for them, with her essentially all-day rehearsal schedule giving her little-to-no time off. The scale of the shows and the extensive travel involved (Bush is famously afraid of traveling by plane) are likely a contributing factor to Bush’s decision to never tour again. A likely further cause is the tragic first night of the tour. During a warm-up concert at Poole, lighting director Bill Duffield fell through an open panel around the stage and landed on a concrete floor 17 feet below. After a week on life support, Duffield died. It was a traumatic moment for everyone involved in the tour, and gave the group pause about whether to continue. When they inevitably did, it was as much as because of the effort put into the shows as it was for Bill himself.

Bush didn’t forget Duffield, keeping tabs as she did on everyone she worked with. The first date of the final London stretch of the tour was a benefit concert for Duffield’s family. The night saw a drastic departure from Bush’s other concerts in many respects: the setlist was significantly different, as Bush wasn’t the only singer performing that night. Two other artists who’d worked with Duffield were present: Steve Harley and Peter Gabriel. Bush had previously worked with established names (e.g. Geoff Emerick), but appearing onstage with established British rock stars was a step forward for her. Harley had scored a #1 single with his glam band Cockney Rebel in 1975 when they released “Make Me Smile (Come Up and See Me),” and didn’t fall out of the albums charts for the next few years. While in 1979 he was hardly the big name he had previously been, with his attempt to go solo beginning with a critically savaged and commercially disappointing album, he had hardly been forgotten by listeners of British pop. Peter Gabriel, however, was at the top of his game. Unlike Harley, Gabriel was confidently traversing through the early years of his post-Genesis career, with the first two of a quartet of self-titled albums under his belt, both of which had made the top 10, and a major solo tour under his belt. The classic “Solsbury Hill” had climbed to #13, and Gabriel was good to go. At the Duffield concert he performed the effervescent “I Don’t Remember,” a wild ballad of the kind of formalist mountain-climbing and despair Gabriel had made his bread and butter while in Genesis. A wailing Kate Bush joins him on backing vocals, and sounds like her larynx is about to combust under the weight of the song’s Frippertonics. Much easier on Bush is a traditional cover of “Let It Be,” a song she’d sung before but still hadn’t made her way into (this would change — wait until this blog hits the late Eighties). Conversely, Gabriel seems to struggle with the song, as Paul McCartney’s gentler songwriting chafed with the new modes of composition he’d been exploring on his own albums and tour. A duo was established, however: Bush and Gabriel would sing together again.

It was a wild time for Bush. “It’s like I’m seeing God, man!” she said enthusiastically. When she’s onstage in a black-and-gold bodysuit and blasting her bandmates with a golden, it’s easy to believe she made that comment while looking in a mirror. It takes a shot of the divine (or perhaps a deal with it?) to stage a tour of this magnitude and success while dealing with such severe drama behind the scenes? It’s no wonder Bush stayed in the studio after this, recording closer to home all the time until she set up a studio in her backyard. Even when she finally returned to the stage thirty-five years later, she made sure her venue was in nearby London. 1979 was a different time. A Labour government was feasible, and Kate Bush was regularly on TV. She plays things close to the chest now, never retiring from music but often looking infuriatingly close to it. In a way, she retired in 1979. Kate Bush the media sensation was a spectacle of the Seventies. She cordoned herself off afterwards, becoming Kate Bush the Artist. Next week we’ll look at Never for Ever, the first post-tour Kate Bush album where she unleashes a flood of ideas into the world. What does one do after the Tour of Life? In Bush’s words: “everything.”

June 29, 2019 @ 9:37 am

Fascinating — and to be honest I enjoyed the work-in-progress versions too. I missed out on this tour, being fractionally too young and too poor to attend, so It’s great to have an exegesis to accompany the Youtube versions.

I initially did a double-take at I Don’t Remember being described in terms of being a Genesis-like ballad, as the album it appeared on was very significant for me, especially in terms of the sound (both Bush’s and Gabriel’s use of the Fairlight excited me far more than most of their successors), and I remember I Don’t Remember as being very spiky.

But I listened to the Youtube version and you’re quite right. The early version he played at the concert really does sound like Genesis. Weirdly, it sounds a bit like post-Gabriel Genesis.