The Zygon Invocation

The recent Zygon two-parter (which I shall, from now on, refer to as ‘The Zygon Inv’ for convenience’s sake) by Peter Harness and Steven Moffat was an extremely well-crafted piece of television in almost every respect. Aesthetic considerations aside, it was a politically committed piece of drama which engaged with vital and loaded current issues. In many ways, it answered a call that I have repeatedly made in recent years for Doctor Who to re-engage with social and political issues, and to position the Doctor as a social actor in struggles. Moreover, it was clearly and unambiguously intended as a liberal statement of tolerance and opposition to war – a surprisingly forthright one, given the current political climate, and the current predicament of the BBC, surrounded on all sides by reactionary hounds baying for its blood.

The recent Zygon two-parter (which I shall, from now on, refer to as ‘The Zygon Inv’ for convenience’s sake) by Peter Harness and Steven Moffat was an extremely well-crafted piece of television in almost every respect. Aesthetic considerations aside, it was a politically committed piece of drama which engaged with vital and loaded current issues. In many ways, it answered a call that I have repeatedly made in recent years for Doctor Who to re-engage with social and political issues, and to position the Doctor as a social actor in struggles. Moreover, it was clearly and unambiguously intended as a liberal statement of tolerance and opposition to war – a surprisingly forthright one, given the current political climate, and the current predicament of the BBC, surrounded on all sides by reactionary hounds baying for its blood.

In many ways, this story shoots for picking up the baton dropped by Malcolm Hulke long ago. Malcolm Hulke was, of course, only the most open and conscious of the many Doctor Who writers to infuse their stories with liberal politics. Yes, I said liberal. In his writing, he reveals himself to be a liberal rather than a communist. Only in ‘The War Games’, in which he and Dicks are pushed leftwards by the cresting wave of the struggles of the 60s, does he look even a bit like a communist. The rest of the time (by the end of ‘The War Games’ actually) he is writing from what is recognisably a liberal perspective. The backbone of his (if you’ll pardon me) whoeuvre is formed by ruminations on racism, bigotry, war, colonialism, corporations, environmentalism, conservatism, authoritarianism, utopianism, etc… and all from a liberal perspective, with all the strengths and weaknesses that this implies. The recent Zygon two-parter succeeds in inheriting the mantle of Malcolm Hulke, and those same structural strengths and weaknesses of liberal politics are still hitching a ride.

Good Liberal Points

I love that the genocide gas which would (ostensibly) turn all the Zygons inside-out was designed by Harry Sullivan. An acute bit of writing. Harry was a bit of a duffer but a jolly fine chap. The product, no doubt, of the English public school system. Rugger, school cups – maybe even a Prefect. No spectacular academic achievements, but he came out with a solid character. And then a medical degree and into the British Navy, where he doubtless served Queen and Country with distinction. Old fashioned and simple hearted. Fine and true. A tribute to the playing fields, old colleges, and institutions of Great Britain. The kind of thoroughly decent sort who was the bread and butter of two world wars. Exactly the sort of person, in other words, to happily exterminate an entire race of inconvenient people for his government.

Then there’s the drone-strike operative at the UNIT base who refuses to press the button and bomb the people in the town because some of them look like her family. Would she press the button without a qualm if they didn’t? Is she usually happy to kill other people’s families? There’s a deeply mordant comment there.

Every position of authority is filled by a woman (except for the Doctor’s) and it extravagantly fails the reverse Bechdel Test. Though there is an issue here. This kind of thing ignores the fact that in the real world women are severely underrepresented in positions of authority. And is it laudable to be in positions of military authority anyway? That’s neoliberal feminism. Girls can grow up to be Condoleezza Rice, hence feminist Utopia. And we trip over an old problem: do you lie about how represented people are in the real world in order to represent them better in the media? How many women judges or black judges are there really in US courts vs. how many turn up in Law & Order?

One line that has been much praised, and been seen as an outright attack on reactionary attitudes, is the “You can’t have the United Kingdom. The people already living there will think you’re going to pinch their benefits” line. Okay, yeah, that’s good line… at least in intent. But what an odd formulation! Nobody seems to have noticed how peculiar this is. “Pinch their benefits” sounds like the Doctor is saying the people receiving benefits will resent the Zygons entering the zero sum benefits-claiming game. It sounds like he’s critiquing the welfare recipients for being paranoid about having their benefits taken away from them by immigrants. In other words, the prejudice about immigrants is the province of poor people. Notice how the choice of language betrays the intended sense. It comes out as victim-blaming, as privileged disdain for the greedy, paranoid, ignorant, bigoted paupers.

Along the same line we have the Doctor’s Union Jack parachute. He says it’s “camouflage”, thus emphasizing that he is not British (underlining the notional conceit that the Doctor is not actually part of the British establishment is a worthwhile thing to do in the context of this story). Sadly, it also underlines the theme of the rest of the story about immigrants hiding amongst us, in disguise.

Us and Them

The story is based on an – at best – only moderately uneasy acceptance of the narrative of Them and Us, with the assumed/aimed-at audience member clearly being one of Us, with the coded discussion being, of course, on the subject of Them.

I genuinely wonder how it would feel to watch this story as a British Muslim. Realising that you are one of the Them that is being philosophised about, that even the Doctor’s sympathy is aimed at you as the other, that you need to be addressed by the culture industries of your society in code, as a subject which needs examination and negotiation. Are you one of the Good Ones or one of the Bad Ones – a distinction nested inside the Them-half of the story’s Us and Them narrative.

I’m interested by the name ‘Turmezistan’ too. Phil called it ‘Generistan’. I think the reason we feel comfortable making up all these generic istans is because we think of those places as generic. Roughly outlined, notional, semi-fictional spaces we see on the news, out There somewhere, populated by Them. Places where bad stuff happens as a matter of course, because that’s the proper place for it. Of course, our culture industries seem happy to pontificate on these generic istans without worrying too much about the fact that we’ve been waging war on one of them for more than a decade.

In the istans Us are always well-intentioned, even if we make stupid and short-sighted mistakes, whereas Them are always… well, Them.

“Isn’t there a solution that doesn’t involve bombing?” asks the Doctor. The ‘we’ve got to do something!’ of the liberal humanitarian interventionist is never questioned -indeed, by the logic of the text, it can’t be. The right of Us to decide how best to handle the problem of Them is never questioned. Instead there is just the squeamishness about bombing. The story sides with the Doctor, of course. But it’s important to note that Kate’s motives are pure, as are the motives of the Rebecca Front character later on. There’s no question but that these people are contemplating invasion, violence, bombing, going in guns-blazing (i.e. Western military intervention) from the best of motives. There’s a real, world-threatening situation that demands a response, and they just want to help solve it.

“This is a splinter group. The rest, the vast majority, want to live in peace. Start bombing and you’ll radicalise the lot – it’s exactly what the splinter group wants!”

It’s terrifying that such basic, baseline common sense should be seen as some kind of exceptionally politically committed statement. This is, essentially, standard liberal hand-wringing. The Good Ones don’t deserve the same treatment as the Bad Ones… and notice how the concern for the Good Ones entails the demonization of the Bad Ones. Would it be okay, O Concerned Liberal, if only the bombs could magically only hit the Bad Ones, the way we’re so often assured they do? After all, the Bad Ones are a Machiavellian threat, sneakily trying to trick us into alienating the Good Ones (our friends by whom we’ve done right). Oh and by the way… all it will take for the Good Ones to turn into Bad Ones will be one little mistake on our part. All Good Ones are Bad Ones in waiting. We want to do the right thing – of course we do! – so we need to avoid being tricked into making a mistake that will trigger the latent unreasoning, irrational, resentful rage of the Good Ones, and turn them into Bad Ones.

Yes, ‘The Zygon Inv’ disputes the crudest reactionary ideas, but it replaces them with deeply problematic liberal ideas still based on condescension (at best), and the assumption of Our own essential and eternal good intentions.

Good Intentions and Original Sin

“Our rights were violated,” says the radicalized young Zygon, “we demand the right to be ourselves.” The very definition of One of the Bad Ones (of Them), taking our hospitality for granted and then demanding more, refusing to assimilate, playing the race card, etc. Of course, coming from a revolutionary, this justification for terrorism is mere cynical sophistry and demagoguery. They’re manufacturing grounds to protest and rebel, the way cynical revolutionaries always do in stuff like this. We never see any evidence that Zygons have been especially badly treated by humanity – certainly not by the forces of bourgeois law and order. All the way through, UNIT’s intentions are honourable. Even when members of UNIT are acting in a bellicose way, they are doing so out of necessity, or in response to provocation, or in an attempt to handle a desperately bad and confusing situation created by the extremists. “It’s not paranoia when it’s real” says the gung-ho UNIT commander. And she’s right. It’s not paranoia because, for her, in this story, it is real. Them really is an ineffable, protean, nihilistic monster perpetually in disguise, capable of presenting itself as your nearest and dearest, etc. The enemy in this story really is everything that is always said about Them in the real world. If Bush had been up against Zygons, the PATRIOT Act would’ve made perfect sense.

Meanwhile, even as it provides narrative logic that entirely justifies such a position, the story also disingenuously asks us to frown on the same position because it comes from Fear. Oh yes, Fear – that wonderfully nebulous, asocial, ahistorical concept which, when decontextualised and generalised into meaninglessness, is so beloved of bourgeois ideology. Irrational, unreasoning, instinctive Fear is certainly why the humans on the ground – the ordinary, non-UNIT humans – mistreat the occasional Zygon. Not being members of any secretive paramilitary organisations affiliated to Western capitalist imperialist states, these ordinary humans can’t be expected to know any better. They succumb to their Fear of the other and attack, like the mindlessly timorous, xenophobic, torch-wielding villagers that most humans are assumed to be in this kind of ideological schema.

Nobody stops to wonder if maybe, just maybe, people should’ve been told. The Doctor and UNIT secretly and unaccountably made the unilateral decision to accommodate Zygons in disguise. They did so on behalf of the entire human race, without telling them. Because the little people – the ones who are not members of any secretive paramilitary organisations affiliated to Western capitalist imperialist states – can’t be trusted to handle this information, or make these decisions. They need an advanced elite to make the decisions for them.

The really interesting and awful thing is that this picture of UNIT organising a secret immigration and settlement program mirrors right-wing paranoia about secretive, unaccountable, elitist, government-organised immigration that takes no account of what people think or want, and puts the native population in danger from immigrants for the sake of bleeding heart political correctness! The high-handed liberalism of the Doctor and UNIT, so praised by the text, is not only let off the hook for causing the very Fear that the Zygon extremists simultaneously protest and wish to cynically use, but is also actually a mirror image of the conservative and racist paranoia peddled by people like UKIP – a paranoia that it accidentally seems to say is justified!

The demand to be able to live openly, as their true selves, is a just demand – even if, within a metaphor about difference, it overstates the alienness of the different. But this demand is presented as just because it is moderate. We judge it reasonable because of its moderation – as if there is something moderate and reasonable about our violent, exploitative, war-addicted, environment-destroying culture that makes us qualified to pass such judgements.

And then it leads directly to fanaticism, violence and terrorism. Even moderate demands lead to ‘extremism’, even as we smile upon them. Having already denied them, despite our liberal approval of them, we find we were right to deny them. Even read more charitably – i.e. as saying that we caused the extremism by denying reasonable demands that we speciously claimed to smile upon – it still posits the Them and Us narrative, with Them as an irrational and over-reacting responder whom we must manage carefully and successfully or provoke into psychopathic rage. Maybe We are prepared to wear a hairshirt for failing to handle Them in the right way, but They are still

a) in need of handling by Us, and

b) ticking timebomb people.

At the end, Kate becomes a mirror of Bonnie – except that Kate is defensive, not a fanatical nihilist like Bonnie

Immigration

The story consciously goes to great lengths to craft a pro-immigrant, anti-xenophobia message… which is rather compromised by the fact that the immigrants in the story are secretly monstrous, blobby, demonic, cephalopodish aliens, some of whom are plotting to take over the world, who set up secret bases UNDER OUR SCHOOLS!!! (the flipside of the otherwise admirable decision to re-establish the link between the Zygons and childhood) and some of whom are involved in terrorism.

It’s true that, in Doctor Who, it’s quite possible to be a monstrous-looking alien and still be a nice person. But, if we’re honest, it’s pretty unusual. For the most part, if you look funny in Doctor Who, you’re probably evil. If you want to write a story which hooks into the (entirely real but marginal) tradition within Doctor Who of representing the apparently monstrous as morally neutral (‘The Sensorites’, ‘Ambassadors of Death’, ‘The Mutants’, etc) then you need to get it right. These days, you probably need to get it righter than they got it in those previous stories, to be honest.

“The invasion has already taken place, bit by bit” we’re told. This is the quintessential expression of the terror of immigration, presented as actually having happened. Yes, this is a threat from one of the Bad Ones… but remember that the plan of the Bad Ones involves revealing the identities of the Good Ones and thus making it necessary for them to fight for their lives. The Bad Ones understand that the Good Ones are just Bad Ones in waiting. Just a nudge – and it will come from Them rather than Us, natch – will set off the inevitable conflagration that lurks as a possibility whenever two cultures try to coexist. This scenario recalls the view of different cultures, discrete and impermeable and incompatible, jostling for limited space, bound to conflict eventually and explode into violence. In other words: multiculturalism has failed. It’s the liberal version of the ‘rivers of blood’ speech.

To be clear: I’m not saying anything of this kind was intended by the writers. But there are big problems here that are baked-in to the entire project of using the alien as a metaphor for the culturally, ethnically, and/or nationally different. Most fundamentally, there is the very concept of ‘difference’ or ‘otherness’. Different from what? Different from Us, of course…. where Us is always implicitly assumed to be, at least on some level, Whitey. There’s a lot more consciousness of diversity (in terms of the demographic reality of UK society and as a representational imperative on TV) these days, and admirable steps are taken to reflect both, but the inherent whiteness – or, to put it less crudely, Westernism – of SF is still with us. It is foundational and structural to the genre. Going back to Wells, the alien is conceived of as alien in relation to Europeans.

The fact that we’re dealing with Zygons aggravates matters. The amorphous nature of the shapeshifter makes them a perfect canvas upon which to project the current nebulous worries of Western culture. The unstable category of the Weird is related to the octopoidal, which is where the Zygons come from, and is probably inherently reactionary. The Zygons are bastardised, third generation copies of the haute Weird. Even so, they carry within them the old charge of incoherence, insanity, incomprehensibility and uncleanliness that the Weird attributed to the different. Just look at Lovecraft. And he was one aspect of a wider cultural movement incorporating Weird motifs. For instance, the octopus spread its tentacles across the globe in late 19th and early 20th century propaganda posters, often standing for the spread of sinister, conspiratorial ‘Asiatic’ or ‘Oriental’ despotisms and other such foreign threats.

The hiddenness of the Zygons in our midst also carries a relevant charge. It recalls an Islamophobic obsession with the burqa and niqab, and other forms of dress which ostensibly make the Muslim women who wear them simultaneously in need of liberation by liberal, feminist Western democratic society and sinisterly hiding themselves (and possibly all sorts of other terrifying things) from the rest of us, even as they enjoy the freedom to move freely among us. If they wear masks, there’s always the possibility that, behind them, they might be one of the Bad Ones. As indeed many of them are in ‘The Zygon Inv’.

Once again, this manifestly isn’t what was intended by the writers. What I’m trying to point out is that there are inherent difficulties posed by the use of this variety of alien (the quasi-Weird shapeshifter) to metaphorically stand for various nebulous ethnic/religious/national groups in society who, in one way or another, are categorised as other. This causes problems automatically and unavoidably which complicate and compromise the obviously conscious progressive intent. I’m really not sniping at Moffat and Harness. I’m trying to make a deep structural, ideological critique of what ‘The Zygon Inv’ invokes.

Passing over the problems created by the way the story wants Zygons to stand for Muslims and immigrants (with these groups equated as both being varieties of the other), and staying with the use of them to represent immigrants, the story moves to New Mexico.

Again, we have what is clearly intended as a liberal, progressive, satirical attack on reactionary attitudes to immigrants. There are signs saying ‘NO BRITISH’ next to signs saying ‘NO DOGS’. What’s being attempted here is a satirical inversion. Hey Brits, how would you feel if you were treated like you treat refugees? Again, there are several problems with this, which stem from the conflict between the intended meaning of the metaphor and the deep structure of how this genre works. Firstly, do ‘we’ all treat immigrants that way? Secondly, the attempted inversion is undercut by the fact that the immigrants being persecuted are not actually British… and we’re never in any doubt about that, which defangs the satire.

This Planet of the Apes-style upside-down-world thing is a deeply problematic tactic for tackling prejudice as it is. You only have to contemplate Planet of the Apes itself, or the Planet of the Gynaecocracy-trope, to see that. Anti-immigrant prejudice is irrational, but the Mexicans of Truth or Consequences have objections to the ‘British’ based on genuine odd behaviour. Even if we take the words of the Zygon/Sheriff – “No jobs, no money… and they were odd… we didn’t want them” – to be unreliable, a parody of prejudice performed for Kate’s benefit, the immigrants the New Mexicans were scared of (and killed) genuinely were dangerous aliens in disguise! Such sentiments are presented as ugly, but the underlying logic of the text makes them justified… or at least justifiable. For all that the episode informs us that we’re not supposed to hate and fear immigrants; it repeatedly depicts immigrants as horrifyingly dangerous. Even if you read the extermination of the townspeople of Truth or Consequences as self-defence on the part of a persecuted Zygon minority, you’re still left with the idea that immigrants come packing potentially genocidal deadly force. The best interpretation of what happened in Truth or Consequences seems to be that there was a misunderstanding followed by a race war that the Zygons happened to win.

Again, the impossibility – or at least intense difficulty – of two cultures living together peacefully is assumed. This tragic impasse is mourned, but also taken for granted. As with the Doctor’s gauche, point-missing parachute, the implication is that, no matter how hard They try to fit in, They’ll never get it quite right. And then the original sin of xenophobia will kick in, and the inevitable cycle of violence will begin again (something backed up by the “fifteenth time” line at the end of the story).

(By the way: it’s highly hypocritical of Doctor Who, which has made a long career out of scaring people with the alien, to wag a finger at us for being xenophobic.)

The race war in Truth or Consequences is part of a cycle of violence between the mythic ‘two tribes’ which feature in standard, ahistorical, bourgeois accounts of conflict. It’s the legend that decontextualises ethnic conflicts and presents war as a product of distrust, fear, and other such inherent failings of fallen man – ignoring that such conflicts are usually the product of historical circumstances, usually to do with imperialism.

Malcolm Hulke’s stories about this stuff suffer from the same failing. He makes the Silurians into potentially genocidal hatemongers, presents xenophobia as a personal flaw and also (incoherently) as a human evolutionary trait, presents an act of military genocide as a well-meaning attempt to save lives, presents a cycle of violence as a tragic consequence of decontextualised things like ‘fear’ etc. All ahistorical, and giving more alibis than condemnations.

As I say, ‘The Zygon Inv’ carries on the grand tradition of Doctor Who in the Hulkean vein.

Assimilation

In line with this assumption of discrete cultures, and intense scepticism about their ability to co-exist, ‘The Zygon Inv’ presents complete assimilation as the only way to achieve and preserve peace. The aliens have to pretend to be like us, pretend to be us, and not show their true selves. Their true selves are monstrous and alien, at least in appearance. (Remember, I’m not trying to single this story out for special opprobrium; I’m trying to show how it is typical in the ways in which it is trapped within snares that seem structurally unavoidable within the confines of SF.) Harmony between Them and Us can only be based on their acceptance of the need to assimilate – but that assimilation is always going to be a lie, a lie that they accept the necessity to tell. Even ‘The Good Ones’ are telling a lie – for their benefit and ours. The ‘Bad Ones’ refuse to tell the lie and show their inner secret monstrousness openly.

The original Zygon story actually avoids this trap, paradoxically by presenting them as all alike. If they are just monsters, rather than being represented as a society or a civilisation or an internally-variable group, they appear purely metaphorical, or as simply things in themselves. Monsters who are metaphors for monstrousness – or for colonialism, especially when set against the backdrop of a Scotland covered in British troops! Make them more social, internally varied, directly metaphorical for recognisable human groups / societies / etc then they instantly take on problematic valences.

The little boy – Sandeep – and his parents are interesting figures. Bringing in an assimilated, presumably second-or-third-generation Asian-British family, and showing them replaced by the monster shapeshifters, is… queasy in light of the episode’s rhetorical insistence upon assimilation. It seems that the laudable aim is to sidestep the implication that the alien other in the story is meant to refer specifically to British Asians… by showing British Asians being persecuted by Zygons just like any other group within British society. Us includes some of Them. All well and good but for the intense emphasis on assimilation. What we end up with is a British-Asian family being used as a vehicle for this insistence.

Zygons take the form of white people too – indeed, the original Zygon command are disguised as the two little white girls. So the Good Ones take the most assimilated form? The ones less assimilated are suspect? Again, this is unfortunate rather than intentional. But these misfortunes are starting to look like a pattern.

Extremism

The story more-or-less openly links its ‘critique’ of ISIS to worries about ‘domestic extremism’, which is surely the absolute failure of assimilation. There is the repeated use of the word “radicalization” with reference to “the younger brood”. Cross reference to the mentions of “training camps” and you have a reflection of tabloid scare stories about young British Muslims going off to fight for ISIS, etc. I guess Zygon parents and ‘community leaders’ should have done more to combat extremism within their community, just as people like Tony Blair always say to British Muslims. They should’ve watched their own young people more carefully to vet their allegiance to western democratic ‘British values’… while, of course, there is no need for Us to combat Our extremism, because Our values are inherently peaceful, as evidenced by the good intentions of UNIT all the way through. Even when UNIT becomes bellicose and ‘overreacts’ it is in response to provocation.

“Don’t think of them as rational. They don’t care about their own people. They think the rest of Zygon kind are traitors. They’re a splinter group.”

Ah yes, the extremists (i.e. the Bad Ones of Them) as ‘irrational’ – a great theme of neo-con thinking and Western imperialist civilisational rhetoric… even as we destroy the world we think of other people as irrational.

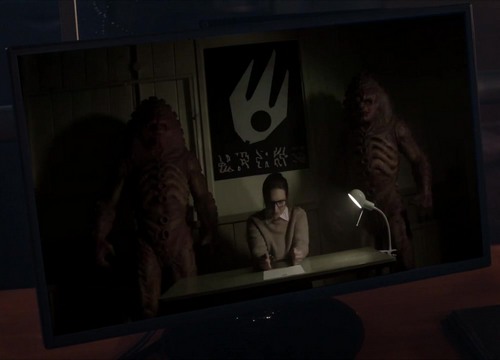

Naturally, the ‘Rebels’ have their ISIS flag, which is also one of those quasi-swastikas that ‘extremist’ groups always have in these things. Are you a generic ‘extremist’, Left or Right or Whatever? Then you need your sinister flag. All non-mainstream political symbols are essentially equivalent in this view. Hence, for instance, the use of the SWP’s clenched-fist logo on the cover of the Big Finish audio ‘The Fearmonger. The symbol of the fascist party is a repurposed logo of a Trotskyist party. Whatever you think about the SWP (and, as I always say, I was never a member and I’m glad of it) they’re not Nazis. But in this emptied, ahistorical, complacent, contentless, contextless view of politics you have the benign centre and the evil extremes, and the supposedly-opposed extremes are essentially mirrors of each other.

Zygon-ISIS uses unarmed women as a cover for terrorists, as human shields. Notice how it’s Them who do this. We don’t talk about how our ‘friends’ do stuff like that, or about equally vile crimes committed by Us. In this text, They have human shields and We are horrified by this terrible thing, which We would never stoop to. Heaven forfend.

Let me be very clear: I have no sympathy for ISIS, but I don’t see that Western capitalist-imperialism has much grounds to wax morally outraged or ethically superior, especially given that it was the horrific crimes of the West against the Middle East that fostered ISIS in the first place.

Needless to say, none of that historical context gets into ‘The Zygon Inv’. (You might say Doctor Who is no place for it… in which case perhaps we should steer clear of the whole topic. If it can only be treated misleadingly in Doctor Who, perhaps Doctor Who should leave it alone. That’s certainly a valid stance, given Doctor Who’s record.)

The Zygon extremist group – which is obviously supposed to remind us of ISIS, at least some of the time – comes out of nowhere, at worst a product of a tragic misunderstanding where maybe some humans (poor, ignorant, xenophobic ones) were to blame, but in which the well-meaning Western government/military establishment is essentially blameless.

Meanwhile, back in the real world, ISIS is the product of genocidal imperialist war/sanctions/interventions in the Middle East by western governments. (Don’t blame me for pursuing their metaphor all the way. They chose it and proudly announced it, not me.) Islamic extremism was sponsored by the West, and is a product of the long-term Western capitalist-imperialist project to destroy Arab nationalism, socialism in the Middle East, etc. No such historical context makes it into this text, which partakes of a bog-standard, ahistorical, liberal, moralistic, finger-wagging sanctimony about ‘cycles of violence’, ‘ethnic distrust’, etc… and that’s when it’s not accidentally slipping into supporting the very ideas it claims to be critiquing.

I’ve made this point before, but why – given the body count that can be laid at the door of British imperialism, old and new – do we have the right to preach our moralistic fables about tolerance and peace? We – if we are to accept the proffered idea of a ‘we’ – should have more shame.

Revolution

The story is as thematically unstable as a Zygon. It declares itself to be about ISIS. Then declares itself to be about ‘immigration’. The story also brings in the issue of revolution. This is entirely extraneous and unforced, and a matter of ideological choice. There was no need to bring in this topic. Consciously or not, the concept/theme of revolution was imported into the story and associated with ISIS.

“We have a Zygon revolution on our hands” someone says. Naturally, a revolution is portrayed as about the worst thing imaginable. And, also naturally, a revolution is the action of a minority. Even as the story falls over itself to disavow any possible Islamophobic interpretation, as it goes to great pains to make all the right noises about how the extremists are in a minority, it also therefore paints revolution as the fanatical, illegitimate actions of an unrepresentative clique.

The fanatics attack the moderates. The Bad Ones attack the Good Ones. (The Good Ones being the ones who do what we want, who keep quiet, who don’t complain or protest, who just go to work and buy stuff, the assimilators. “I’m not part of your fight. I never wanted to fight anyone. I just wanted to live here. Why can’t I just live?” The Good Ones are the ones who don’t fight us.) The anti-Islamophobic bet-hedging becomes the standard liberal narrative about revolution. The Bad Ones are forcing change on the majority who don’t need or want it. They are cynical, like all revolutionaries, not really sincere in their specious devotion to freedom. We, meanwhile, are of course entirely sincere. By definition.

“Then we will die in the fire rather than living in chains,” says Bonnie. This is supposed to terrify us. These are the words of a fanatic. The story takes it for granted that such rhetoric is insincere and chilling. I find it wonderful. This is the kind of political statement almost designed to make me cheer… except that, in this context, it has been given to the standard villainous revolutionary of bourgeois ideology: cynical, nihilistic, cruel, callous, fanatical.

Note how even in this statement, the bourgeois assumptions creep in and deform what should sound like a ringing clarion call for emancipation. The chains are unreal, a product of the extremist’s fevered imagination. The fire is of the extremist’s own making. The choice is between doing nothing and death. There is no chance of success in this schema – despite the fact that many peoples and nations have liberated themselves from slavery and colonialism by use of fiery rhetoric and revolutionary violence. No, Toussaint L’Ouverture never happened, and Haiti escaped slavery by waiting for the inevitable progress brought by enlightened liberal Western civilisation, always peace-loving by definition no matter how many wars it starts. Thus, as always, the collective mind of bourgeois civilisation forgets its own crimes and congratulates itself (inaccurately) on solving the very problems it caused in the first place.

All the same, I refuse to disapprove of, or disavow, anyone who says “we will die in the fire rather than living in chains”. Never.

Notice the Doctor’s argument with Bonnie’s objections based on history. Yes, he says, history is history, it’s all in the past – but what do we do now? You know, I lost track of the number of times, in the run up to the invasion of Iraq, when I would tell people about the hideous crimes of the West with regards to Iraq – our complicity in Saddam’s rise, in his slaughter of the Iraqi Left, in selling him arms, in supporting his war against Iran, in sticking by him when he gassed the Kurds, about the coalition armies slaughtering the Iraqi people after the invasion of Kuwait, about the genocidal sanctions regime imposed by the UN – only to be countered with the breathtaking cynicism of “yes yes, that’s all very well, but that’s history… what do we do now about Saddam, eh?” As if it was ‘our’ job to ‘do something’, to be the saviours jumping in to decide the fate of the Iraqi people for them. As if ‘we’ could be trusted to have their best interests at heart after such a sordid history of violence, betrayal, exploitation and support for tyranny. But that’s another of the eternal cries of the bourgeois obfuscator, always desperate to find a way of respectably grovelling to the imperatives of power: “we’ve got to do something!” NATO’s catastrophic intervention in Libya was justified by the same old gaggle of useful idiots with the cry “Benghazi!” as they swallowed the media’s hysteria hook line and sinker. They are so quick to discount history because they want to avoid learning from it.

People have praised the Doctor’s great speech at the end of the second episode. Personally, I don’t think I’ve ever hated the Doctor more than at that moment. Reject the cycle of violence, says he, in favour of ‘forgiveness’. It is, of course, for the revolutionary to stop the cycle… the established power doesn’t have to because they want peace and forgiveness by definition. It is for the oppressed to forgive. The onus is on them. They must bear the burden of the greater moral responsibility. They must be the ones to prove their good intent, etc. Reluctance to do so is to be mocked as childishness, as a tantrum. As is the dream of Utopia (explicitly raised in order to be knocked down). It’s a childish dream because you haven’t got a plan. You need to have minutely detailed schematics and blueprints for the new society drawn up in advance before you can be taken seriously, before you can challenge the existence of the old – even if the old is killing you. Because the bourgeois imagination cannot handle the idea of actual freedom. Freedom, to bourgeois culture, is the freedom to be an atomised individual, a shopper, a voter, a taxpayer, a law-abiding citizen, one of the Zygons who just wants to live here and be left alone, etc. That’s the best there is in the impoverished, philistine bourgeois imagination. It can’t handle the idea of real freedom, radical freedom, freedom that doesn’t work like an RPG, freedom that’s more than the structurally circumscribed licence to move around inside pre-set limits. Even as it eternally chides the revolutionary for wanting just this, this is all it offers. Unless the revolutionary has those detailed schematics, then she is not to be taken seriously. She is just a dreamer, a utopian, a head-in-the-clouds fantasist, playing around with people’s lives for cynical, self-serving, self-deluding reasons. Of course, if the revolutionist does present you with the plans you demanded to see, you can then denounce her as wanting to force everyone to live the way she wants them to live.

“Sit down and talk,” says the Doctor. Oh marvellous. Why didn’t the Palestinians think of that!? Or the blacks in apartheid South Africa? Or the Kikuyu in British-dominated Kenya? Or the Herero and Namaqua in German-dominated Namibia? Or the Native Americans? Or the Congolese in Belgian-dominated Congo? Or the slaves in San Domingue? (I could go on.) Don’t fight! Don’t try to overthrow and chuck out your oppressors – just be reasonable, sit down and talk. After all, all ‘we’ ever want is a reasonable negotiating partner, right? ‘We’ always mean well and want peace, by definition. If only these truculent, trouble-making, zealous, fanatical rebels would calm down, stop causing the problems, and talk to us. I’m sure we could thrash out an equitable arrangement. A nice compromise – between the powerless and their oppressors.

(You might object that the extremist Zygon faction in the story doesn’t fit this model… they’re not particularly oppressed, they’re not natives, they’re ISIS in disguise, etc. But ‘The Zygon Inv’ chooses to tell this story that way. It chooses to invoke revolution against oppression and associate it with a thoroughly unsympathetic ISIS analogue who have no real claim to the moral high ground.)

Of course, in turns out that all revolutionaries need is a good talking to from a nice, liberal compromiser. Stand your revolution down, says the Doctor. And then he forgives them. I’m sorry but just who the hell is he to forgive them? Are we really so arrogant in our culture that we think it is for us to claim the role of father confessor to the rest of the world? Just how sick and twisted is it that an imperialist culture, drastically culpable in creating the turmoil that created ISIS, thinks it has the right to produce morality fables about war? Morality fables which, moreover, accord to us the moral high ground and the right to arbitrate, the right to preach about forgiveness, about the need to sit down and talk? Who the hell do we think we are that we get to absolve anyone?

(Again, you might quibble with me that Moffat and Harness didn’t invade Iraq. But they are working within the confines of the BBC – an organisation that works as an organisation of state propaganda. Just as it went into overdrive normalising and legitimising the Iraq invasion, so it still drums up support for other ‘interventions’, and supports the establishment’s view of things on topic after topic, from Israel-Palestine to Scottish Independence. And the story in question chooses to engage in the very narrative of Us and Them that lumps all aspects of Britain in together, uncritically accepting the idea of the ‘national community’. If we’re all one lump, then by that logic, the writers, the BBC, Doctor Who, are all part of the same lump that includes the British government, the Ministry of Defence, the Army and the RAF, etc. They can’t them claim an exception later.)

The Doctor goes on to preach about how great it will be on the day nobody cares about the answer to the question of who is a Zygon and who is a human. This is horribly reminiscent of “Oh, I don’t even see colour”. The Doctor and Osgood touched on the “not knowing the difference” thing earlier, back on the Presidential plane. Osgood is the alibi the text uses as its trump card. Unity, and refusal to distinguish, is the key to peace. But Our insistence upon Them losing Their identity is Their grievance, and Our solution is to force Them to accept Our view of whom and what They should be. Notice that Osgood is supposedly both human and Zygon but looks fully human in both her iterations. I don’t think it really makes much difference, in the end, if this comes from budgetary concerns.

And, of course, the Doctor’s settlement, like the original treaty, is resolutely undemocratic. It takes effect without any of the mass of people who are effected even being consulted. It’s all decided in a little room by about three people. And that’s a moral victory for freedom, apparently.

Allegory

Of course much of this is business as usual for Doctor Who, going back years. Let’s just not pretend this represents any great new low for political comment in the show, anymore than a new high. This is depressingly usual fare.

In any epoch the dominant ideas will be the ideas of the ruling class, and bourgeois society manufactures consent in multifarious ways, with the spectacle reproducing the relations of capital, and ideology becoming a vast web of interlocking ideas which constantly reproduce themselves, leading to a cultural hegemony which means that all aspects of social life – from manners to taste to bedtime stories – reflect the…

*sigh*

Look, aside from all that, the problem is fundamentally one that has long dogged Doctor Who, and the kind of socially-aware SF that forms this strain within Doctor Who. It is the problem of metaphor. Or perhaps I mean the problem of allegory, because metaphor only really becomes problematic in this way when it slides into becoming allegory. (There’s an aside to be made about pre-modern forms of allegory compared to modern forms, but we’ll skip it.) The structure of SF entails an allegorical mode of address. That’s the strength of the genre that opens it to discussions of wider issues… and yet there is a paradox built-into it which is that this (modern) allegorical approach means presenting issues which are fundamentally historical in ahistorical terms. It’s like reducing actual events to formulae. You end up distorting things, without meaning to. The temptation is always there to use the technique of reductive allegorical formulae to Say Stuff about the world, sometimes possibly angry, radical, incendiary stuff. And I get that temptation. Shit, do I get it. Trouble is, this formulaic reduction is also highly convivial to the kind of reductionist narratives about complex historical and political events that we get presented to us by bourgeois ideology. The reduced, formulaic version then becomes interpretable in terms of dominant narratives – the narratives of the dominant, which are the background or framework surrounding the allegory as a kind of vast cultural paratext.

Ultimately it is only by slipping the chains of allegory and direct one-to-one signification that SF/Fantasy can escape this paradox. The interesting thing is that this leap from the realm of necessity to the realm of freedom in narrative is the exact mirror of the same leap that, in actual human social relations, would only be possible through – indeed could only be – social revolution. The very social revolution that texts like ‘The Zygon Inv’ relentlessly assure us to be impossible, unworkable, immature, irrational, dangerous, unnecessary and evil.

Unhappy Ending

Phil once very kindly expressed his appreciation of my writing in terms of what he sees as my determination to demand perfection of the world. I think this is a fair characterisation, but I’d like to make it clear that this is a conscious decision on my part, inspired by the politics of the old slogan of the soixante-huitards ‘Be reasonable – demand the impossible’. I have previously stated my attraction to the idea of keeping one’s politics childish, in the sense of holding fast to that childhood characteristic of demanding fairness, and being surprised and angry when it doesn’t materialise, no matter how many jaded adults remind you that nobody ever said life was fair. Because, you see, that’s a lie. They did. They did tell us that life was fair. Repeatedly. They still do. Every day. On TV, in films, in books, in newspapers… they tell us that life is fair over and over again, in happy ending after happy ending, in fictional moral victory upon fictional moral victory, in reassuring news story after reassuring news story, in editorial after thinkpiece after review. It’s only when we express anger at injustice that we are dishonestly told that justice is an unreasonable expectation. The point is to convince us that the class-ridden, woman-hating, racist, exploitative, war-ridden world of poverty, starvation, misery, wastage, and insanity that we have to live in is the best of all possible worlds… and then to chide us for asking to live in the best possible world if we ever notice that we don’t. So, all in all, I think that the tactic of childishly stamping one’s foot at the world and saying “not good enough” is rather a charged one, and rather tactically powerful.

There is a strain of the revolutionary, the genuinely radical, in Doctor Who. It’s real and it’s in there, against all odds. I love it and I cherish it. But the fact is that it is only one strain amongst many, and is far from the most prevalent, consistent or uncompromised. Indeed, its existence could reasonably be said to be pure – if repeated – fluke. That it was more common in the classic series is owing to the fact that a great chunk of the classic series was made in the era of social democracy, during which socialism worth the name (revolutionary or reformist) was not the dead parrot it is usually thought to be now, the British working class was not yet as compromised a category or a group as it is today, and there were still great social struggles in which the Left were not entirely marginalised. Even from about the classic series’ middle age, when neoliberalism was born and began its ascendancy, there was still resistance. Neoliberalism finally triumphed in Britain only roundabout the time of Season 22 (I hate to slip into crude determinism, but it’s highly tempting to suspect more than a coincidence there). Some revenantal junk-DNA aside, the new series is an artefact of neoliberalism entirely. Most of it is a product of post-Great Recession neoliberalism, which – contrary to myth – is not neoliberalism-discredited but rather neoliberalism-reasserted, entrenched, unleashed. Zombie-neoliberalism: dead but still here, and more ferocious, more dangerous, more unhinged, more fearless, more cannibalistic. That’s what produces new Doctor Who. That it retains any of its old ability to sometimes sleepwalk into radical critique, or into the realms of the radically emancipatory, is because of its peculiar pre-life as a text born in the historical context of social democracy, and its peculiar site of production: the still-not-entirely subsumed BBC. But these blips are rarer than ever, and getting rarer. And they are still only that: blips.

‘The Zygon Inv’ is no such blip. It is a true, noble and faithful inheritor of a venerable tradition within Doctor Who: the Hulkean liberal parable. And that is surely a relatively good thing to be. There are worse things in the world. And it is, if I’m honest with myself, in many ways, truer to the real soul of Doctor Who than my beloved blips. But that’s all it is: just a liberal parable. And, as such, for me it is thoroughly unlovable. As thoroughly unlovable as I should and would find the great bulk of classic Doctor Who, if I were as intellectually honest with myself as I should be.

The truth is that I found watching ‘The Zygon Inv’ a wearisome, dispiriting, deeply unhappy experience… not so much because of anything wrong with the story itself, but rather because, as it unfolded, it seemed to have been designed to demonstrate to me that, blips aside, I don’t really like Doctor Who, not even old Doctor Who. It’s not a happy experience to realise that you don’t really like something that has consumed a great deal of your interest and passion throughout your life. It’s bad enough knowing what I always knew: that I was emotionally and intellectually over-invested in a commodity. Messers Harness and Moffat have, with ‘The Zygon Inv’ ably demonstrated to me that I have also allowed myself to focus too much on the blips.

I think some people expected me to savage Harness and Moffat. On the contrary, I want to praise them for writing something that demonstrates the best of normal Doctor Who.

November 12, 2015 @ 5:55 am

I still maintain that the message of this story is nothing to do with revolution or assimilation or anything like that. It’s about acceptance of responsibility and choosing to break the cycle in a positive fashion. It’s about living with your decision and, crucially, understanding its implications. And that has to come from both sides.

It’s perhaps easiest to depict in the form that was chosen here, because there’s a ready-made “establishment” model in the form of UNIT (and, notably, the Doctor clearly remains disappointed with them, even at the end of this story.)

And yes, whilst I wholly agree with you that some of the positions presented here as being “correct” are extremely questionable, I am still prepared to take away from this story an extremely positive position on breaking the cycle, rather than a wholly negative one related to a perceived failure of allegory.

November 12, 2015 @ 10:44 am

If anybody had turned on the Doctor and pointed out that this was all his doing in the first place, it would have been a lot stronger, as far as taking responsibility goes.

By the way, did anybody notice the little ret-con tweak to Zygon society where they said they actually WANT to live as disguised shape-shifters? It’s like they saw the corner they were painting themselves into…but the lifeline the threw themselves just doesn’t work on any level. It’s the “happy slaves” thing all over again.

(Except I suppose it could explain why Broton was happy to live for centuries impersonating the local gentry, before he arsed himself to try to take over the world, pro forma.)

November 12, 2015 @ 11:10 am

It’s pretty explicitly flagged as a retcon in the opening to Invasion, where the Osgoods describe Zygon shapeshifting specifically as an ability to allow assimilation.

I’m unbothered by it, mainly because I think “assimilated immigrant” and “slave” are pretty starkly different as moral concepts.

November 12, 2015 @ 12:08 pm

Obviously they are different. But I meant it in the sense of Doctor Who writers bending over backwards to create an alien species who crave things that in the real world are, mm, problematic at least, thus allowing them to side-step the question of whether asking them to give up their physical forms and culture, basically to disappear as a species, as a condition of not being murdered is in any way reasonable.

November 14, 2015 @ 11:24 pm

There is a difference between assimilation and cultural genocide, as well.

The Zygons using their shape-shifting as a tool to adapt and ease interactions with others makes sense. Forcing Zygons into a situation where they have to adapt a single non-Zygon identity, and “pass” with 100% success, is quite different.

A better analogy than slavery might be the idea of Jews in Europe during WWII trying to survive by passing as Gentiles. Not just getting the right papers, but having to completely hide who and what they are, and even very young children knowing that their lives and the lives of everyone they care for depends on never, ever making the slightest mistake.

Immigrants and refugees routinely adapt to the new culture they are living in. Wear local clothing styles. Adapt favorite foodways to the ingredients available in the new location. Zygons choosing to using a non-Zygon form as part of adapting to their situation, in a flexible way, would be like that – having times and places to be Zygon, and times and places where they will use the common local form.

The so-called treaty was effectively being secret Jews in WWII Europe. Even a child making a small mistake in public was a disaster, leading to violence.

The Doctor says that they’ve been through this situation fifteen times before.

Did it not occur to anyone that the treaty wasn’t working in its current form? That having a subpopulation in permanent disguise was not a long-term solution? That without being given good information and a chance to learn to accept, humans would never magically reach a stage where they were ready to accept?

During the initial crisis, when there were twenty million refugees needing a place with the resources to absorb this type of population increase, and to be able to feed and house everyone, the treaty was likely a good way to get people settled quickly, before the Zygons began suffering from the disease and scarcity that comes with being a large group of displaced people.

November 12, 2015 @ 3:40 pm

I never got the impression that Broton had been impersonating local gentry for centuries (a la Cessair of Diplos). The fact that there was a Duke of Forgill to survive until the end of the story suggests that that particular impersonation was a pretty recent development.

November 13, 2015 @ 6:36 am

Bonnie did turn on the Doctor and point out that this was all his doing in the first place:

BONNIE: You are responsible for all the violence. All of the suffering.

DOCTOR: No, I’m not.

BONNIE: Yes.

DOCTOR: No.

BONNIE: Yes. You engineered this situation, Doctor. This is your fault.

DOCTOR: No, it’s not. It’s your fault.

BONNIE: I had to do what I’ve done.

DOCTOR: So did I.

BONNIE: We’ve been treated like cattle.

DOCTOR: So what.

BONNIE: We’ve been left to fend for ourselves.

DOCTOR: So’s everyone.

BONNIE: It’s not fair.

DOCTOR: Oh, it’s not fair! Oh, I didn’t realise that it was not fair!

November 20, 2015 @ 11:00 am

Isn’t that exacty exactly what happens when Bonnie says “This is all your fault”?

November 12, 2015 @ 7:01 am

The point at which things really turned sour for me here was when the Doctor mocked Bonnie for the idea that it was enough to just want a homeland. Even without the political signifiers elsewhere in the story, it was hard to see this as anything other than a reference to Palestine. The idea that we should criticise Palestinian revolutionaries because they haven’t explained what they’ll do in their homes once they have them back is sickening. “What comes next?” “Hey, how about we just don’t keep getting FUCKING MURDERED?”

November 12, 2015 @ 7:01 am

Wow!

However…

While I agree with pretty much all your critique and you have eloquently expressed all my discomfort with Zygon Inv. I think a child watching this story might actually take away a vague echo of the ‘blips’ you describe as rare incidents in Who. The concepts of ‘morality’ of ‘decency’ and ‘fair play’ while obvious paper tigers and false ideals here are nonetheless not inherently bad things to wish for. As you (and the situationists) say ‘Be reasonable – demand the impossible’. Surely Moffatt and Harness here are ascribing entirely to your dictum of keeping politics childish.

I think the attempt falls down (and if I’ve understood your diatribe you might agree) because the writers have built a ridiculous straw man argument and attempted to clothe it in ‘concerns torn from today’s headlines’. Equating an invading force of octopoid, electro stinger wielding, sucker covered blobby creatures FROM ANOTHER PLANET with concerns around immigration in the UK and the US and then also throwing in ISIS for good measure is at best naive allegory and at worst bloody stupid.

I still love Doctor Who but they do make that hard to justify sometimes.

November 12, 2015 @ 8:09 am

“Then we will die in the fire rather than living in chains,” says Bonnie. This is supposed to terrify us. These are the words of a fanatic. The story takes it for granted that such rhetoric is insincere and chilling. I find it wonderful. This is the kind of political statement almost designed to make me cheer.”

Yes, Jack, it makes you cheer… because you never had to deal with it and you know there is absolutely no risk of you having to deal with it someday. During your lifetime, there never was and never will be a Great Revolution of All of America’s Minorities, or a Great Rebellion of the East Against the West. So you can have your cake and eat it too: you can make your big, risky political statement, and then you can go on, business as usual, because you know that the risk of you (or anyone) “dying in the fire” is nil.

November 12, 2015 @ 8:50 am

There’s something to that, of course. For someone as comfortable as me, there’s probably always going to be a degree of armchair generalling about it. But then I’m also very unlikely to die in the fire (or starvation, or whatever) unleashed by ‘our’ imperialist adventures. It’s a question of which fire-that-I’m-personally-unlikely-to-die-in I decide to support – the one that empowers and bolsters aggressive imperialism, or the one that a) is defensive, and b) has a liberatory potential.

November 12, 2015 @ 9:10 am

Jack, the fact is that a war is nothing to cheer about, ever. That’s kinda the point of the episode: it doesn’t say that violent revolution is always and forever wrong, but that it should always be the final option. The Zygons had a treaty and diplomatic relations with the humans, so the choice was between the slower path and the fast but messier one. The episodes decide that the first one is better.

November 12, 2015 @ 9:43 am

…having chosen to write the scenario in such a way as to paint revolutionary resistance to oppression as unreasonable and akin to ISIS, Exalt.

November 12, 2015 @ 10:18 am

Not “revolutionary resistance” in general, THIS specific revolution.

Also, in the analysis you completely ignore the fact that, in the end, not only Bonnie doesn’t suffer any consequences for her actions, but, on the contrary, she becomes the new leader of the Zygons. This is not your standard fate for generic-DW-baddie: the idea is that now she can continue her revolution, but in a slower way that does not involve killing most/all humans and who-knows-how-many- Zygons in the crossfire (assuming her not-exactly-sure victory).

And the episode does not present the final result as a great victory, but as the lesser of two evils, a compromise brought upon by the fact that the alternative is worse (and, to be clear, worse in these specific circumstances).

The message is not “figthing is always wrong, always”, but “war is not a nice thing to be in, so please, PLEASE, think well about it before starting one”. I don’t think that is an unreasonable demand.

November 12, 2015 @ 10:53 am

Yes, that’s how they choose to depict these matters. I have issues with that choice. See above.

November 12, 2015 @ 10:20 am

Because the majority of revolutions are certainly reasonable and not doomed to become as twisted as their oppressors. I’ve seen these revolutionaries first-hand, and they spew their “for the people” rhetoric only as a way to sound morally superior when they’re only just the old guard but with different paint. Western imperialism may be vile, but it’s only one of many rather than the chief direct conductor of atrocities in the Middle East. You may see Marxism as a perfect alternative to capitalist decadence, but my experiences have only taught me the difference between a militant Marxist and a militant Capitalist is about the same as red ants and black ants.

November 12, 2015 @ 10:20 am

Thank you for this. I half-thought a lot of this while watching, but I didn’t quite have the framework to express what I thought was wrong with it.

November 12, 2015 @ 10:53 am

‘No such historical context makes it into this text’ – wouldn’t ‘Day of the Doctor’ – the Doctor, UNIT, & that story’s Zygons’ decision to allow Zygons to hatch, breed, & assimilate into human civilization while keeping it all secret – be that ‘historical context’?

November 12, 2015 @ 10:54 am

It’s the in-universe context, sure. The continuity context. I was thinking more of something referring to real historical context.

November 12, 2015 @ 11:18 am

“Nobody stops to wonder if maybe, just maybe, people should’ve been told.” that actually bothered me more than anything.

November 12, 2015 @ 11:24 am

Shameless self-promotion, but the interview with Harness in Guided by the Beauty of Their Weapons discusses that at some length.

(Preorder at http://www.amazon.com/Guided-Beauty-Their-Weapons-Science-ebook/dp/B0172TJQDI and whatnot)

November 13, 2015 @ 6:12 am

Will this be getting a paperback release, or is it Kindle only?

November 12, 2015 @ 1:01 pm

This gets it pretty much spot on, to my mind. What at one time would have just exposed the limits of can’t-we-all-just-get-along liberalism now seems almost radical, now the floor has been so comprehensively lowered all around it. It’s a sobering thought.

One kind-of caveat, though. I suspect everybody guessed the button boxes were going to be empty. But what is unexpected is that its Bonnie who susses that. As that scene went on I was pretty much convinced it would end with her pressing the button, frantically and repeatedly, before realising the futility of her action and with it the folly of her motives. And she susses while Kate doesn’t, in fact Kate has failed to for the nth time. Which does suggest its her status as an outsider that gives her perspective Kate lacks. Kate has a role in this society and aims to fulfil it, hence she makes the same action over and over. Bonnie takes a step back and sees, to some degree at least, things for what they are.

But overall… like you say…

November 12, 2015 @ 2:10 pm

Great analysis: it’s especially telling that Kate, as the human/UNIT representative, gets her memory wiped at the end of the episode. It’s not simply that humanity doesn’t get to find out the Zygons are here and try to learn to live with them, it’s that Kate isn’t allowed to learn from her role in the whole affair. Still, I think the episode opens up a lot of room for discussion of the issue in ways that, say, the “would you time-travel to murder Hitler” doesn’t. And I think it’s fair to say that this ending represents an advancement from the ending of And the Silurians.

One place where I’d push back strongly against your analysis, though: the Doctor’s long speech. Who the hell is he to forgive them? I feel like you missed the part where he explains that he’s a far bigger war criminal than Bonnie could ever hope to be, and that he not only holds onto the memory of that shame but that he uses it to try to prevent others from doing what he did. If one insists on extending the analogy, this would be like an American leader expressing deep shame over what was done to the various Native American tribes and vowing to prevent others from doing the same things; granted, the Doctor isn’t redressing the wrongs he’s done. Part of the power of this speech comes from the sense in which the Doctor knows what’s really unforgiveable, and that isn’t Bonnie’s revolution (that, I’ll point out, kills plenty of people).

And I’m not convinced that some of the Doctor’s needling (especially the “childish” accusation) was meant to be taken as what he genuinely believed. He was trying to provoke her into thinking, into rethinking, and he picked an accusation he figured would hit home because SHE didn’t want to be seen as childish. After all, as any adult knows, there’s no point in being grown-up if you can’t be childish sometimes.

Two last thoughts: I think reviewers so far have been missing the importance of “thinking like” someone else to the story. Sure, Osgood’s conveniently taken on human form, but if the human Osgood is trying to “think like” a Zygon, does that matter more than her physical appearance? Can an Israeli “think like” a Palestinian?

Also, as a though experiment, consider these two episodes again but from the standpoint of Zygons as closeted homosexuals. How would that reinflect our understanding of what went down and our satisfaction with the conclusion, which demands that Zygons remain so closeted that humanity can’t even start to accept their presence because they remain ignorant of it?

November 12, 2015 @ 5:01 pm

I understand that the next episode of the (excellent) Web of Queer Podcast is going to touch upon a queer reading of this story – which should be interesting.

March 3, 2019 @ 10:07 pm

More than three years late to this comment section, but I’m a gay guy who grew up extremely repressed for my own personal safety and I was mortified at this scene. I could not help but sympathise with the Zygons as being somewhat analogous to closeted gay people and the doctor’s speech as suggesting that the stonewall riots were a morally abhorrent act of terrorism. His remark of “so what” in response to Bonnie’s complaints about the repression left a really sour taste and I actually stopped watching the series after watching this clip. However, even my distaste for this scene was completely dwarfed by my horror at reading the comment section and finding that almost everybody was praising the speech as being insightful and just as opposed to what it really was: A slap in the face to every repressed minority in history.

November 12, 2015 @ 2:54 pm

In the end Bonnie was the one who had the agency and the power. She was given the choice. What I took away from the “15 times” line is Kate and UNIT had to be manipulated, banged over the head again and again until they made the right decision. The Zygons were actually treated with some respect.

November 12, 2015 @ 5:18 pm

The truth is that I found watching ‘The Zygon Inv’ a wearisome, dispiriting, deeply unhappy experience… not so much because of anything wrong with the story itself, but rather because, as it unfolded, it seemed to have been designed to demonstrate to me that, blips aside, I don’t really like Doctor Who, not even old Doctor Who. It’s not a happy experience to realise that you don’t really like something that has consumed a great deal of your interest and passion throughout your life. It’s bad enough knowing what I always knew: that I was emotionally and intellectually over-invested in a commodity. Messers Harness and Moffat have, with ‘The Zygon Inv’ ably demonstrated to me that I have also allowed myself to focus too much on the blips.

Oh my. You seem to have found the words I’ve spent two years looking for. Thank you.

I started out really liking this episode, but over the course of today, partly but not entirely independent of this article, it occurred to me that Bonnie’s central argument is #ZygonLivesMatter, and the Doctor’s central argument “Nope. All lives matter.” (A position I zeroed in on in the third blog post I’ve done on this episode in the past two days: http://blog.trenchcoatsoft.com/2015/11/12/the-zygon-apotheosis/ )

November 12, 2015 @ 5:57 pm

I find it interesting that you have such disdain for the Tivolians when you apparently think the human race should passively accept the arrival of 20 million technologically advanced shapeshifters whose race has attempted outright conquest twice in the last 40 years (the first time in an overtly genocidal form) before finally “settling” for assimilation.

Also, if not the Doctor, then who /does/ have the moral authority of “forgive” the Zygons? The friends and family members of everyone slaughtered in Truth or Consequences (pop. 6411 per wiki)? The mother of that soldier brutally murdered by the Zygon made up to look like his mother? None of those people have any say in the matter — they’re just little people.

November 12, 2015 @ 11:52 pm

A stunning essay, Jack. Thank you for this.

November 13, 2015 @ 7:32 am

I think we’re approaching the limits of what Doctor Who can reasonably be expected do. Nothing is inflexible, not even an ageless alien who can travel any time and anywhere. This is evident from the fact that Moffat is three Doctors in, and he’s still basically writing for Tennant and his hoochie companions.

The longer the series goes on, the more it becomes hamstrung by convention and capitalist oversight. Toss in some towering actor/producer egos and you have safe, vanilla, middlebrow entertainment which goes for broke on fanservice and cheesy meta marketing.

November 13, 2015 @ 7:39 am

What makes watching Doctor Who frustrating is that it continually hints at subversions it hasn’t quite got the faith to follow through on.

There are constant feints at a more joined up critique of the kinds of power relations typically enacted in popular adventure stories. There is the vaguest whiff of liberation, the sense of a story that can revisit and comment on and disrupt entirely any other story.

The hint is in the vision of His Nibs as a one man revolutionary wave, a spectre haunting the galaxy,

arriving at sites of oppression and critiquing them to death. And from the ruins of the old, new growth.

Ultimately, the message is muddled, the consequences of the critique are fudged and out come the big empty words – peace, forgiveness -and the great liberal back-pedal begins. The hinted subversion turns to business as usual but with an aura of hard-won wisdom to be displayed proudly as proof of compassion.

Bit of a pisser…

November 13, 2015 @ 9:40 am

Imagine if Truth and Consequences had been in Mississippi or Alabama. Nina Simone Mississippi Goddam: https://youtu.be/fVQjGGJVSXc

November 13, 2015 @ 9:59 am

I think all the problem with this episode could summarized with a bizzare contradiction in vilification of rebels. Not because they killed humans and zygons, no sir. This is oddly forgiven.

But for trying to tell the world truth. This is her crime.

“Humans will murder all the Zygons they find! Also, what oppression you are talking about?”

November 15, 2015 @ 7:46 pm

I am reminded of something Fred Clark at Slacktivist writes about, the obligation to “afflict the comfortable, and comfort the afflicted.”

This episode seems to work when it follows that rule, and stumble when it gets it backwards.

Afflict the comfortable white, western audience for showing insufficient hospitality and welcome to frightened, desperate refugees? It does that beautifully.

Show the fear and confusion of a Zygon child attacked because it was too young to perfectly hide? Could have been better.

But shaming a member of a minority forced into hiding and chaffing under the restrictions? Not so good. Framing the story so that the minority must hide for the sake of the comfort of the majority, indefinitely, and completely impractically? Fail.

And if you haven’t read Slacktivist, particularly his decade-plus deconstruction of the “Left Behind” series, I highly recommend it for folks who like the stuff here. They may be the World’s Worst Books, but Fred’s take on them is a labor of ethics, story analysis, theology, morality, humor, and kindness.

http://www.patheos.com/blogs/slacktivist/2015/11/05/left-behind-index-the-whole-thing/

November 16, 2015 @ 4:17 am

The reality is that it’s a smear on people who are genuine in their concern for immigration. I know it’s the Biased Broadcast Cast (BBC) and all but we let our children watch these things! If I wanted them in any way subject to politics I’d put them in law school, or at least put the daily politics on once in a while. But I do not, and I chose to sit and watch doctor who with my family. As I have done since I was my sons age. Yet I find rhetoric on a children’s TV program that was trying to indoctrinate children into new Liberalism, so no! I do not find it in any way tolerable. It is outrageous. Given that the show has declined ever since Moffat became “top dog” I’d say making political indoctrinations is certainly not the way Doctor Who should go. My son knows very well that immigrants are not coming to Britain purely for benefits. I’ve helped him understand immigrants come here because they can. Because we cannot them any more, because of mass immigration our nation is no longer a nation. I am not a bigot or a “pudding brain” that’s simply fact. I do not condone Doctor Who taking a political stance in any direction. The doctor should steer clear from that!

November 16, 2015 @ 12:22 pm

This is a splendid essay, Jack. It’s a lot like “The Zygon Inv” in that even though (because, really) I didn’t agree with every word I enjoyed it thoroughly.

Your penultimate paragraph really hit home for me too. I was a huge fan of the show as a kid, started losing interest during the McCoy years (for a variety of reasons), eventually set it aside almost completely during the Wilderness Years and especially after the TV Movie, and so when it came back it took me three years even to begin to trust that it might be worth rekindling the flame for. I’ve since spent perhaps (definitely) too much time and money on it, and occasionally stop to realize with a shock that I’m watching other shows with great enthusiasm and fascination, while watching this one with gritted teeth just hoping, hoping for a miracle.

And yet it maintains its grip on me. I think there’s something about those blips for you and the ones for me that probably partially but not completely intersect with yours that remind us of the potential of the premise, the truly amazing moments lurking between the ones we see that surely MUST be there. The part of the show the BBC shows us is never going to go as far as we want it to (and anyway you and I have somewhat different directions in mind), and yet it implies time after time that it could. The tension between what we see and what we want to see is just taut enough to keep us there, isn’t it? It’s almost better this way. It’s almost the only way it would keep our attention in the long run.

“The Zygon Inv” is, if nothing else, worth talking about. I don’t think we should regret it. You definitely shouldn’t.

November 29, 2015 @ 7:25 am

This is just a brilliant piece, really thought-provoking and I’m sad I didn’t come across it until just now. It’s a source of great sadness to me that Doctor Who really probably isn’t as good as Doctor Who fans willing to invest this much brainy analysis into it deserve. And I really don’t think Moffat is the showrunner under whom it’s going to get much closer to being that good… but one day, one day, maybe.

September 17, 2016 @ 11:40 pm

If this is how Jack responds to an overwhelmingly liberal story, just think how he’d respond to a conservative one!

October 31, 2023 @ 3:40 am

My criticism of this piece would be the almost dualistic moralising at play ; privileging historical, aggregate injustices as a result of systemic oppression over the aggregated injustices of movements like violent revolutionaries tending towards hegemonic approaches to concepts of justice, as if theirs is the only acceptable kind, and thus beyond legitimate questioning.

True justice may elude liberal capitalist society, but there is a wildly inhuman dimension to treating class-struggle almost purely as an economic calculation of injustices – “the bourgeoise have a history of bloodguilt to condemn them by, we are blameless by comparison”; the disparity in the model apologists of violence put forward in the weight of a shared collective guilt for historical injustices that can only be erased by conformity to the revolutionary’s puritanism, versus any given individual’s innocence in a contemporary context for historical injustices truly boggles the mind when this seems to setup a situation where it becomes merely a disagreement between who gets to indicate the “bad guy”; the revolutionary is always justified by this line of rhetoric, and can never be said to commit injustice because all such criticism is inescapably illegitimate in their eyes.

Within Marxist movements, there’s sometimes an acceptance or rationalisation of particular injustices as necessary sacrifices for the advancement of the revolution. These particular injustices — be they aimed at individuals, certain groups, or occurring in the process of revolutionary activities—might be seen as a regrettable but necessary means to achieve the larger goal of systemic change. In this process, however, there can be a tendency to forget that these individual instances of injustice, when aggregated or when certain categories of injustices are consistently disregarded, contribute to broader systemic injustices.

November 22, 2023 @ 6:39 pm

I don’t see a Scottish man referring to assign a Union Jack as“camouflage”, in a year where 56/59 parts of Scotland voted to be represented by pro-independence representatives, who were explicitly calling for greater immigration and tolerance of immigrants, as highlighting a point about immigrants “hiding among us.