The_OA Exegesis: New Colossus

Before we begin, I’d like you to reach out and touch the screen you’re reading this from. Is it hot or cold to the touch? Glossy or matte? I bet it’s hard. You wouldn’t want to put your hand through this “glass” even if you could get it fixed for free. Notice how your hand obscures the light.

Before we begin, I’d like you to reach out and touch the screen you’re reading this from. Is it hot or cold to the touch? Glossy or matte? I bet it’s hard. You wouldn’t want to put your hand through this “glass” even if you could get it fixed for free. Notice how your hand obscures the light.

Close your eyes, and let out a faint breath, little more than a hisssss. Remember this feeling.

I’ll wait.

Remember. You know who you are.

Chapter Two

The Statue of Liberty is formally known as La Liberté éclairant le monde – Liberty Enlightening the World. That’s a great name. In the previous essay, we talked about the symbolism of eyes and the metaphor of sight in The_OA. This is a show that is not just concerned with the visible plot or what is “literally” happening, but also (and moreso, I think) with the invisible meaning we can derive from the text (including the text of our lives). The_OA provides a window to such inner workings through the repeated use of certain thematic elements, so when Chapter 2 opens up with an image of the EYES of the Statue of Liberty, becoming visible under the influence of photo developing chemicals as clear as WATER (another important motif in Chapter 1), I think it’s trying to signal something important. More important than just a location for some of the plot to take place in.

And there are a lot of neat referents around La Liberté in this chapter. Perhaps most obviously, she appears in a dream to Prairie, where she’s climbing the face of the statue, right over her eyes, and then suddenly she is somehow inside Liberty herself, back-lit by the Crown’s windows, and it is here she finds her father holding many candles deep in the dark. Prairie believes this is more than a dream – after all, she can see in this dream… and she’s having nosebleeds (when Prairie cleans it up in the bathroom, running the Water in the sink, Nancy comes in and says, “Let me see it in the light”) – and as such she takes it as a premonition, as if she were clairvoyant.

To get to Liberty, Prairie takes a Greyhound bus – greyhounds are sight hounds rather than scent hounds. She crosses over water in a Ferry (we’ll go back to this) to get to the Island (and we’ll go back to this), where we see all kinds of people milling about taking pictures (remember the picture of Liberty at the beginning, and young Nina having her picture taken with the Johnsons), and many more are wearing crowns, holding torches, as if everyone but Prairie herself were an avatar of Liberty. All kinds of little beats that incorporate Liberty into the language of The_OA: water and snow, sight and light.

And then there’s the reading of the plaque, which is the poem dedicated to Liberty by the poet Emma Lazarus (oh what a name, how apt for this show):

Not like the brazen giant of Greek fame,

With conquering limbs astride from land to land;

Here at our sea-washed, sunset gates shall stand

A mighty woman with a torch, whose flame

Is the imprisoned lightning, and her name

MOTHER OF EXILES. From her beacon-hand

Glows world-wide welcome; her mild eyes command

The air-bridged harbor that twin cities frame.

“Keep, ancient lands, your storied pomp!” cries she

With silent lips. “Give me your tired, your poor,

Your huddled masses yearning to breathe free,

The wretched refuse of your teeming shore.

Send these, the homeless, tempest-tost to me,

I lift my lamp beside the golden door!”

So much of this poem fits into the thematic paradigm of The_OA: “sea-washed, sunset gates,” a union of Light and Water; the invocation to the Homeless, which is how OA is identified in Chapter 1; lifting the Light again, but now by the golden Door, and how important “doors” were in Chapter 1.  The harbor that twin-cities frame is “air-bridged,” which has a whole new meaning after our discussion of Bridges in the first chapter. And then there’s the Torch, the Light of Liberty, and how is that its flame is “imprisoned lightning”? As if putting the Light inside a prison could make it a Beacon, that glows world-wide?

The harbor that twin-cities frame is “air-bridged,” which has a whole new meaning after our discussion of Bridges in the first chapter. And then there’s the Torch, the Light of Liberty, and how is that its flame is “imprisoned lightning”? As if putting the Light inside a prison could make it a Beacon, that glows world-wide?

One’s tempted to juxtapose the Liberty of this poem with OA herself. Because OA has started to nurture her own little band of exiles – Steven, rebelling against authority; Jesse, who has withdrawn from the world; BBA, the teacher who tries to manipulate the system; Alfonso “French” Sosa, who simply complies with it… and Buck, who is perhaps the most exiled of all, considering he’s trans. None of these people “fit” into the power structures of the world, and that includes OA. As we’ll see, she’s already had the experience of being “imprisoned lightning” (how deeply ironic that her visit to Liberty leads to her capture and imprisonment, which she gets into of her own free will, and which is ultimately intertwined with her disappearance and hence no longer being seen by the light of day) and even now, supposedly free after all that, she still feels “cooped up” with the Johnsons, as if she were a caged bird.

(I’d also like to touch on OA’s father, Azarov, who appears with his own torch – a candelabra, more like – in her dreams. “Azar” means “fire,” so her Father is “of the fire,” and as such is a source of Light and Heat. He is the main juxtaposition to so much of the “cold” that gets highlighted in this show.

Sometimes, in mythology, a nearly mythological “father” figure is a metaphor for God. Consider this passage:

AZAROV: It’s like hide-and-seek. Right now we are hiding. Can you stay hidden a little longer?

NINA: Because of you, I know I can do anything.

AZAROV: You can do anything.

And this one:

OA: He was my lifeline. And I was his. Every Sunday, we saved each other. We shed our skins and plotted the future.

It’s not unreasonable to consider Azarov as a metaphor, then. But what does that mean? How are we supposed to take this as a metaphor? I don’t think it’s a theological statement, if that’s where you thought I was going with this. Rather, it might be a way to contextualize our experience with the divine. For example, Prairie follows a vision of her Father, and it ends up profoundly changing her life, and not necessarily for the better. But her experience of the Father is nonetheless one that gives her confidence. Both are “saved” by the relationship, and of course the absence of her Father, the way he stays hidden – well, if there is any deity in the Universe, “hidden” is a great descriptor.

We might also look at how characters think of Azarov as a window into their souls – Nina, for example, still believes her Father is alive; she’s still a believer. Her aunt, on the other hand, is convinced that Azarov is dead; she has no faith but in money. Of course, to take this position possibly ascribes a potentially uncharitable perspective to the showrunners, Brit Marling and Zal Batmanglij. However, consider that Prairie will eventually come to choose other people over her Father, and it makes more sense; it’s not a belief in God that makes you good, but a belief in people.)

Finally, let’s consider the passage that’s not spoken out loud by the park ranger in VO while Prairie prepares to get on the Ferry – the first two lines:

Finally, let’s consider the passage that’s not spoken out loud by the park ranger in VO while Prairie prepares to get on the Ferry – the first two lines:

Not like the brazen giant of Greek fame,

With conquering limbs astride from land to land;

This is in reference to one of the Seven Wonders of the World, a very famous antiquity that didn’t last as long as it should have: The Colossus of Rhodes. It was a bronze statue of the sun-god Helios, on the Greek island of Rhodes. It was built in 280 B.C., paid for by the abandoned siege equipment of a failed conquering army. Over a 100 feet high, on a pedestal nearly half that height, it stayed up for only 54 years, when an earthquake knocked it down.

To you, O Sun, the people of Dorian Rhodes set up this bronze statue reaching to Olympus, when they had pacified the waves of war and crowned their city with the spoils taken from the enemy. Not only over the seas but also on land did they kindle the lovely torch of freedom and independence. For to the descendants of Herakles belongs dominion over sea and land.

The dedication to this Wonder of the World led those in the Middle Ages to imagine that the Statue actually straddled the mouth of the harbor; Emma Lazarus’s poem picks up on this misconception, with the legs “astride from land to land.” Similarly, the Titan of Braavos in Game of Thrones (okay, A Song of Ice and Fire), a similar giant statue, is something a ship can pass under. This is also the case in Sergio Leone’s movie Colossus of Rhodes, a very interesting picture where the Statue itself takes on some almost metaphysical properties, as what happens with the Statue either reflects or will be reflected by the characters and environment around it. We’ll return to this movie in Chapter Five so that we may reflect on some compelling imagery.

Regardless of how the Colossus was actually posed, though, like Lady Liberty herself it was a giant figure surrounded by water, as befits an Island.

Cold Water

Cold Water

We talked in the last essay about how Water is a kind “bridge” in The_OA, so let’s see if that reading still stands up. As we just noticed, Prairie crosses a small underground stream in Hap’s “lab” before she becomes his prisoner. It would make a hell of a lot of sense if this study of Near Death Experiencers also happened to include a number of Near Death Experiences. I guess we’ll have to wait and see. 😉

But there’s also Prairie’s ferry ride to and from the Island upon which Liberty stands. We’ve already pointed out, this too corresponds to part of Prairie’s understanding (or misunderstanding) of Death, as this journey was precipitated by a premonition, and her first premonition was a precursor to an experience of The Other Side. Calling the boat to Liberty Island a “ferry” conjures up the thought of the Ferry that crosses The River Styx in Greek mythology, an integral image of the death experience. Reinforcing this interpretation is the fact that Liberty is actually on an Island – after last episode’s multiple invocations of the word “lost” (reiterated here with “1ostboy” sending broken bridge pictures to Alfonso), I can’t help but think of the connection – especially when Alfonso sees a snowglobe with Liberty inside that glass, as in LOST the Island was at one point referred to as a “snowglobe.” Or maybe there’s a Fringe connection, as that too had Liberty snowglobes presented as a twinset, with one smashing into the other as a metaphor for parallel universes smashing into each other. Anyways, I find the snowglobe significant regardless of intertextuality – it’s Liberty inside a bubble of glass (we’ll get to this), drowned in water (the Bridge), and with falling “snow” to boot (snow is “cold water” in particular). In other words, that snowglobe inherently partakes of the visual language that The_OA has established.

Another significant “water shot” occurs when Nina is taking a bath while Nancy shampoos her hair in preparation for having their pictures taken. When Nancy lowers Nina’s head into the water, half submerging it, the little girl hears the voices of the other children who were in the bus with her on the day they all drowned.

Another significant “water shot” occurs when Nina is taking a bath while Nancy shampoos her hair in preparation for having their pictures taken. When Nancy lowers Nina’s head into the water, half submerging it, the little girl hears the voices of the other children who were in the bus with her on the day they all drowned.

As much as the Water motif gets reiterated in this chapter, the cold might get more. We really didn’t talk about the cold much in the previous episode – there’s the bit where Azarov teaches Nina to beat her dream by embracing the water, much like the cold is defeated by one’s being colder than the cold, a lesson taught in ice water. OA herself is told she had hypothermia by the nurse in Saint Louis. Moscow is shown blanketed in snow, and in Michigan it’s winter – the video that OA posted on YouTube is dated February 9th, 2016.

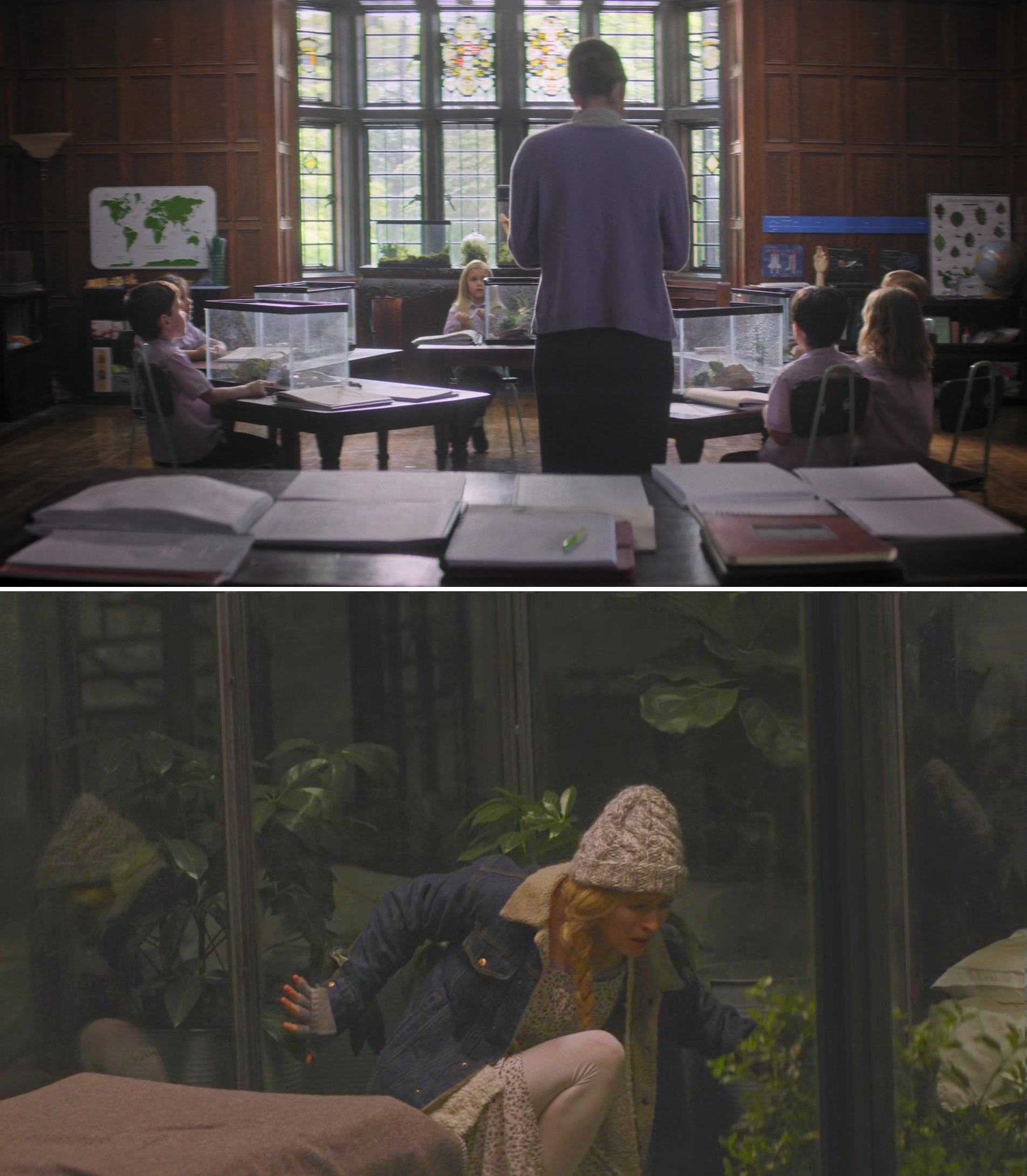

Here we get similar beats. As we said, there’s the Liberty snow globe in the principal’s office. French is tasked with bringing back milk for his mother’s coffee before “it turns into an ice cube,” and Buck explains his eating of ice cream as being a matter of liking “cold stuff in the cold,” (to which French says “cool.”) The teacher at the beginning of the episode asks the children what kind of bloodedness the snakes have, to which they all say “Cold!” (I like that beat.) And as for young Nina’s experience of staying at her aunt’s whorehouse, OA says, “It was cold where I slept.”

So what does it mean to be cold? At least in The_OA? I think it kind of means what it means—but not so much in terms of temperature as it is in temperament. Being “colder than the cold” is a way of shutting one’s self down, of being cold-hearted towards one’s circumstance and environment; it’s a form of stoicism. Buck, for example, after talking about the ice cream, is stoic about his parents’ historical misgendering of him. French, on the other hand, is genuinely cold to Buck about going back to listen to OA’s story, but I guess since Buck was colder than cold, he got French to change his mind. Nina’s experience in the whorehouse was not a loving one, but a cold one.

Despite the oft coinciding of cold and water, however, not all water is cold.

HAP: All right. Here we go. You take this, put it up to your mouth, and you just slurp the oyster down like you’re sucking sea water out of a shell.

PRAIRIE: Oh.

HAP: All right, I hated my first one, too. Uh, can we get some fries, please? But everything good in this world takes, uh, getting used to. Right, I remember my first coffee in college. I wanted to throw up. But by the end of medical school, I couldn’t get out of bed without a double shot.

Obviously, most people drink their coffee hot, but more importantly, oysters generally aren’t slurped down cold, either. And given that in the dialogue it’s described as “sucking sea water,” (the “sea” being a pun of “see”), maybe we should reconsider the Oyster Bar experience as more than a bit of comic relief, especially given how Prairie’s life changes over this meal.

First, this incident, and Prairie being told to take her medications with a glass of water, introduces a new motif that’s going to become very important going forward (it actually goes back to Nina’s breakfast of eggs in Chapter 1, but we’re forgiven for not picking up on it right then), which is that of swallowing. Swallowing (funny how there’s a bird called a swallow) of course reminds of phrases like “swallowing a story,” of engaging in some kind of belief and internalizing it. Taking her medications is a form of buying into the values and perspective of the Johnsons, and the medical establishment at large. And of course, it’s in the Oyster Bar that Prairie swallows Hap’s story.

But there’s more going on here, because the oyster is likened to sea-water, which as we noted earlier indicates a Bridge, a connection between the Ordinary World and the Other Side. This will have other implications for Prairie in the next few chapters, but for now I want to also consider the fact that it’s from oysters that we get Pearls. And there’s a very interesting story about pearls that is relevant here. (Hmm, would we call the guts of an oyster “pearl jam”?)

That story is called The Hymn of the Pearl, which comes to us from the apocryphal Acts of Thomas, one of the gnostic gospels. The Pearl tells the story of a young man (probably Thomas, whose name means “twin”) sent by his parents (his father is described as a “king of kings) to fetch a mythic Pearl from a mighty Serpent (hmm, snakes again?) in Egypt. The young man gets to Egypt, where he is tricked into eating their food, and falls into a stupor; he becomes a “slave” to their king. But his parents know the truth, and send him a letter:

It flew in the form of the Eagle,

Of all the winged tribes the king-bird;

It flew and alighted beside me,

And turned into speech altogether.

At its voice and the sound of its winging,

I waked and arose from my deep sleep.

There’s our bird symbolism again! Anyways, the man fetches the Pearl and brings it back to his homeland, and he once again gets to wear the “glorious robe” of his birthright; it’s as if his very flesh were bejeweled. All of this is a metaphor, of course – in this myth, we are all Divine, but we have forgotten that as we enter this mortal coil, and so we need to hear a Message that will help us to remember. Then we can wrest our sense of divinity back from a meaningless world and create meaning within it, simply by recognizing (re-cognizing) the “invisible” self in ourselves and in others.

And this is a really apt way to describe OA’s journey in life. Her time with the Johnsons, despite them being good people, is dulled and numbed by medication; she’s taught to forget her dreams and understanding of her birthright. Now she meets Hap, and from an upcoming deep dive she will hear a “message” and retrieve a “pearl” from this experience.

Hunter Aloysius Percy

So let’s talk about Hap. Before getting into any of his evil, though, we’ll start with his name, because it’s an interesting name worth deconstructing. The first name is easy – he’s a Hunter, hunting down NDE survivors and collecting them for his research. “Aloysius” is not so obvious. The name is a Latinized form of an Occitan version of “Louis.” Which is immediately interesting, given the location of Saint Louis as where OA jumped off the bridge at the beginning of the series. There is a “Saint Aloysius Gonzaga” who joined the Jesuits and renounced his inheritance rights; he later had a vision of the Archangel Gabriel, prophesizing his death within the year, a dream that came true, and as such has resonance with OA’s experiences (not to mention identity). “Louis” derives from “Ludwig,” which means “famous warrior” – here, Hap’s work is a part of some “holy war” between “science” and “faith.”

“Percy” is just as interesting. While it originally comes from a place name in Normandy, this is fairly mundane; better to examine its connotations as the short form of Percival or Perseus. “Perseus” possibly derives from the Greek perthein, which means to “waste, ravage, sack, destroy.” The figure of Perseus in ancient Greek mythology, most famously known for taking the head of Medusa, was a Mycenaean warrior (and eventually king) – now we get resonances with both “Ludwig” and “Hunter.”

The story of Percival, on the other hand, only goes back to the 12th Century, but it concerns the Holy Grail. Percival is raised in the forest by his mother after his father’s death, so Percy is unaware of his heritage. He admires the heroism of knights and sets out to become one, but his mother has taught him to not ask questions so as not to look a fool. He becomes a part of King Arthur’s court, a full-fledged knight. But on the way back home to see his mother, he encounters the Fisher King, a wounded man who takes Percy to his castle, where at dinner (hmm, swallowing things) the knight is repeatedly shown a procession bearing a “bleeding lance” and a “candelabra” and especially an elaborately decorated “Grail.” He asks nothing, though, and wakes up in the morning to find everything is gone. Later, it comes to light that he could have healed the Fisher King by asking an appropriate question, namely, “Whom does this Grail serve?”

(Interesting tidbit, most people think of a Grail as a chalice or cup, but a “graal” was actually a kind of serving plate, shaped like a long shallow bowl.)

(Interesting tidbit, most people think of a Grail as a chalice or cup, but a “graal” was actually a kind of serving plate, shaped like a long shallow bowl.)

Again, this is a metaphor and a lesson—the Grail (in which a single Mass wafer is placed) symbolizes a container of the Divine, obviously. Thinking back to The Pearl and “glorious robes,” then, our bodies are containers for the Divine. The question of “Whom does this Grail serve?” then becomes poignant. To what do we devote our lives? To an ethos of imminent and inherent value, extended to all people, or to the aggrandizement of our own egos? Hap’s story is that he wants to find answers to unanswerable questions, especially the question of death and the Other Side, which strongly resonates with Prairie, but Hap is too invested in his own ego, not only as a “scientist” but also as someone who is too scared of losing himself to journey to the Other Side on his own accord. “Ego” is precisely the flaw of Percival, who doesn’t want to appear foolish, rather than being motivated by pure concern for the wounded Fisher or genuine curiosity in the mythic procession.

Finally, we have the nickname of “Hap” – which is short for “to happen” and is generally used to refer to luck, lot, fate, or accident. Hap is “lucky” to find Prairie, as it happens entirely by chance, not by design. And equally, Prairie meets the hunter by “hap” but her fate is not so lucky. “Hap” can also refer to a quilt or comforter, by the etymology of Middle English happen which means “to cover” and itself is possibly a blend of lappen (“lap”) and happer (“to seize”). Again, the idea of the material world as a “cover” for the invisible world (namely the “invisible self” of which OA speaks in Chapter 1) comes to mind, as does OA’s move to put a blanket over her head when she leaves her parents’ car upon her return to Crestwood. Hap wants to uncover the invisible world of The Other Side, and actually wants to seize it, but he only wants to do it while retaining his sense of the material world as being what actually matters… and I wonder if this is because it’s only in this sense that Hap has any power, as he’s not exactly an inspirational character.

Prairie cast a “beautiful net” but she did not catch something beautiful—she was looking for her true father, but found a false one instead. This also relates to Gnostic concepts, namely that what most people take as “God” in certain Abrahamic texts is actually a false deity known as a “demiurge” that is the creator of a lesser material world and that is actually responsible for the existence of suffering.  So Hap is the “false god” wanting to deliver a false vision of the promised land, for of course the Other Side isn’t a place we find through “material fact” but through an internal process that’s often called “faith,” which would include a belief in one’s invisible self.

So Hap is the “false god” wanting to deliver a false vision of the promised land, for of course the Other Side isn’t a place we find through “material fact” but through an internal process that’s often called “faith,” which would include a belief in one’s invisible self.

Here, then, we might start getting another resonance with the meaning of “cold” in the text of The_OA. Hap worries what Prairie (prayer-y) would have thought of him “if you walked into a freezing house.” His airplane ride takes her up to the “heavens” with all those clouds, but it’s cold outside when he implores her to open the window. And Hap used to be an anesthesiologist – someone trained to knock you out cold, leaving you completely numb to the rest of the world.

Interesting shot from the interior of the plane. Those diagonal lines look like a letter or something.

Homeward Bound

TEACHER: You are brilliant! And your snakes are tired, so please return them to their homes and we’ll return to our textbooks.

– – – – – – – – –

HEADMISTRESS: I’m sorry, Nina. You have to go home.

NINA: But I don’t have a home until he comes and we make one!

Again, the word “home” appears 11 times in this Chapter, though this time it includes the name of Homer. This is such an important thread for The_OA, so of course we have to return to it. OA brings its up over and over again in the first half of this chapter, in the context of Mrs. Valen’s School for the Blind (Valen means “strong, vigorous, healthy”) and with her father’s plans for escape.  At Aunt Zoya’s whorehouse (Zoya derives from Zoe, meaning “alive,” which in this context is ironic but still within the thematic flavor of the show), the word “home” comes up only as “homework,” until the Johnsons show up and take her back to their place: “Welcome to your new home,” they announce as they bring her inside.

At Aunt Zoya’s whorehouse (Zoya derives from Zoe, meaning “alive,” which in this context is ironic but still within the thematic flavor of the show), the word “home” comes up only as “homework,” until the Johnsons show up and take her back to their place: “Welcome to your new home,” they announce as they bring her inside.

And at first it’s a place of freedom for Nina. She gets to walk around barefoot, learns to climb trees, and read books in Braille. So it should not be surprising that we get a Bird motif in this montage (with Nancy’s face reflected in that picture next to the stairs) followed by a tree (the usual home for birds), but it’s the story that Nina reads that’s absolutely delicious. This story is Jack and the Beanstalk.

Young Jack is supposed to sell the family cow at market, but ends up trading it for magic beans, much to his mother’s derisive consternation. Jack, however, has faith and plants the beans, and a giant beanstalk grows up to the heavens. Jack makes his climb three times, stealing gold, then a hen that lays golden eggs, and finally a golden harp before he’s found out and has to make his escape—by chopping down the beanstalk and killing the “fee fie foe fum” giant.

As with most faerie tales, this can be interpreted alchemically. The beanstalk is a World Tree of sorts, an axis mundi that connects Above and Below. Jack’s ascensions to get “gold” correspond to the “rubedo” phase of The Great Work – he needs not just wealth, or a means of generating wealth, but an actual “song” or spiritual awakening to be whole and free. This is precisely the kind of journey that Prairie is going to have to take for her own spiritual development; this is also another way of expressing the underlying concepts of The Hymn of the Pearl.

Nina is given a new identity at the Johnsons’ home. She’s named Prairie (rhymes like PRAYER-Y), after the blue sky color of her EYES, quite ironic considering she’s a blind girl. Nancy intends to give Prairie a “blank slate” (the albedo stage of the Great Work) – to her, this is an opportunity for rebirth. But it all goes wrong, because despite their great hearts, the Johnsons do not represent spiritual enlightenment. They want to make Prairie “an American Girl” – which is the brand name of a manufactured line of plastic Dolls and accessories.

It’s at this point that the Johnsons’ home becomes a place that reiterates some motifs from the first chapter of The_OA, and in a way that has interesting narrative implications. Obviously, the Dollhouse (and dolls) were filmed by OA in Chapter 1, and were used by her to begin her journey with the Five, calling them to the Abandoned House; here the Dollhouse is filmed by Abel. There’s no mystery to solve in this instance, but there were other narrative minor mysteries that become resolved both in this segment and elsewhere in Chapter 2. For example, we see the ritual of taking off one’s shoes in the home – which is simply a rule the Johnsons have. The bit of Russian that we hear on the video camera in Chapter 1 is explained – that was Nina as a child, recorded by Abel. The collection of knives in Nancy’s desk now makes sense, as in Nina’s sleepwalking we see her pick up and wield a knife, which is what prompted Nancy’s intervention in that scene.

The Johnsons just don’t understand Nina’s interiority. Nina was told by her father not to tell their secret, so how could the Johnsons have known the truth? They ultimately end up lacking faith in this little girl, and resort to the structures of authority to deal with her – in particular, they turn to a doctor. Who begins years of medication to numb Prairie into compliance. This is revisited when OA returns to their home:

NANCY: Maybe the doctor in Saint Louis was right, and we… we took you home too soon. Maybe you need time in medical care.

It’s expressed as concern, but it’s downright chilling—Nancy is actually considering have her daughter locked up, so much does she fear he daughter’s freedom. And this isn’t the only instance of doctors being invoked in such a fashion in this text—French shows his contempt for his alcoholic mother by saying she should see a doctor, and Hap consulted other doctors about his first experience with a flatlined patient, and of course they dismiss his observations of hearing a “whoosh” as “everybody thinks they feel something.” (Again, this is not to say that I hold this opinion of doctors, or that The_OA is telling us to ditch them in real life; rather, this is a symbolic role that doctors play in The_OA, which is also shared by other authority figures.)

So Prairie is shut up, and learns to keep secrets. A point that is reiterated in her final scene at the Johnsons before she sets out for New York—she’s had one of the “those dreams,” you know, the kind the make her nose bleed – and here, after Nancy cleans her up, she says, “Let’s not tell your father.”

Underground Apocryphon

Underground Apocryphon

As you might have noticed, the “spiritual” inclinations of The_OA lean towards the apocryphal, rather than canonical orthodoxies. An “apocryphon” is a “secret writing” (“apocrypha” is the plural) and this derives from the Greek apokryphos, which means “hidden, obscure.” Esoteric, in other words. In the context of Biblical literature, though, it refers to unknown authorship, and hence unknown authority, which is how the word “apocryphal” developed a connotation of “dubious”… which relates to The_OA’s hinting at unreliable narration, which begs the question of how we can (and should) go about interpreting the text in light of that.

But in the more traditional sense of what’s apocryphal, let’s consider the role of “secrets” within in this story, because there are an awful lot of them. In terms of the meta-text, we had a lot of secrets or mysteries in Chapter 1 – why does OA jump off a bridge? What does she mean by “we all died more times than I can count”? What happened to her during the time she was gone? What about all those scars on her back? How did she regain her sight? And so on.

In Chapter 2, there’s more of an emphasis on secrets held by the characters for their own purposes, rather than hiding things from the readers of the text. Oh sure, there’s still a bit of that – what is Hap doing? for example, or not providing closed-captioned translations of certain Russian phrases in scenes where the Johnsons wouldn’t understand what was being spoken. And there are Easter Eggs, like what’s on the TV in the background when French comes home to tell his mother about the scholarship.

This is the chapter where we get things like Azarov saying that he and Nina are in “hiding” from the Russian mob, and Nina is supposed to stop speaking Russian to facilitate that. Nina believes that her father is “sneaking” messages to her in her dreams. Her Aunt Zoya hides the fact that these babies she’s adopting out come from her escorts, not women pursuing their college dreams. Nancy and Abel agree not to tell anyone of Nina’s origins, and later on Nina wants to hide Prairie’s nosebleed from Abel.

OA’s very storytelling is based on a secret: she’s not telling her parents what she’s doing, and the Five aren’t telling anyone either. French hides his cocaine use. Prairie can’t read Lady Liberty’s plaque, because it’s not in Braille, so this is a secret from her that someone else needs to reveal. Hap, of course, hides NDE survivors in his basement; that’s quite a secret!

And this whole business of hiding and secrets plays into character motivation. Buck wants to know how it will end, not just OA’s story, but the story of the Five people OA’s gathered. Hap wants to uncover the secret truth of Near Death Experiences. Prairie wants to find the truth of her dreams, despite her parents’ use of medications to suppress them, and she wants to find her hidden father. This repression, by the way, manifested for her as a child, leads her to walk in her sleep. Beyond this, there’s the matter of the “invisible self” that OA talked about in the previous chapter. It’s something that can’t be seen, hidden from ordinary sight, only revealed through our choices. And hell, we often even aren’t aware of our own invisible self, when it comes down to it.

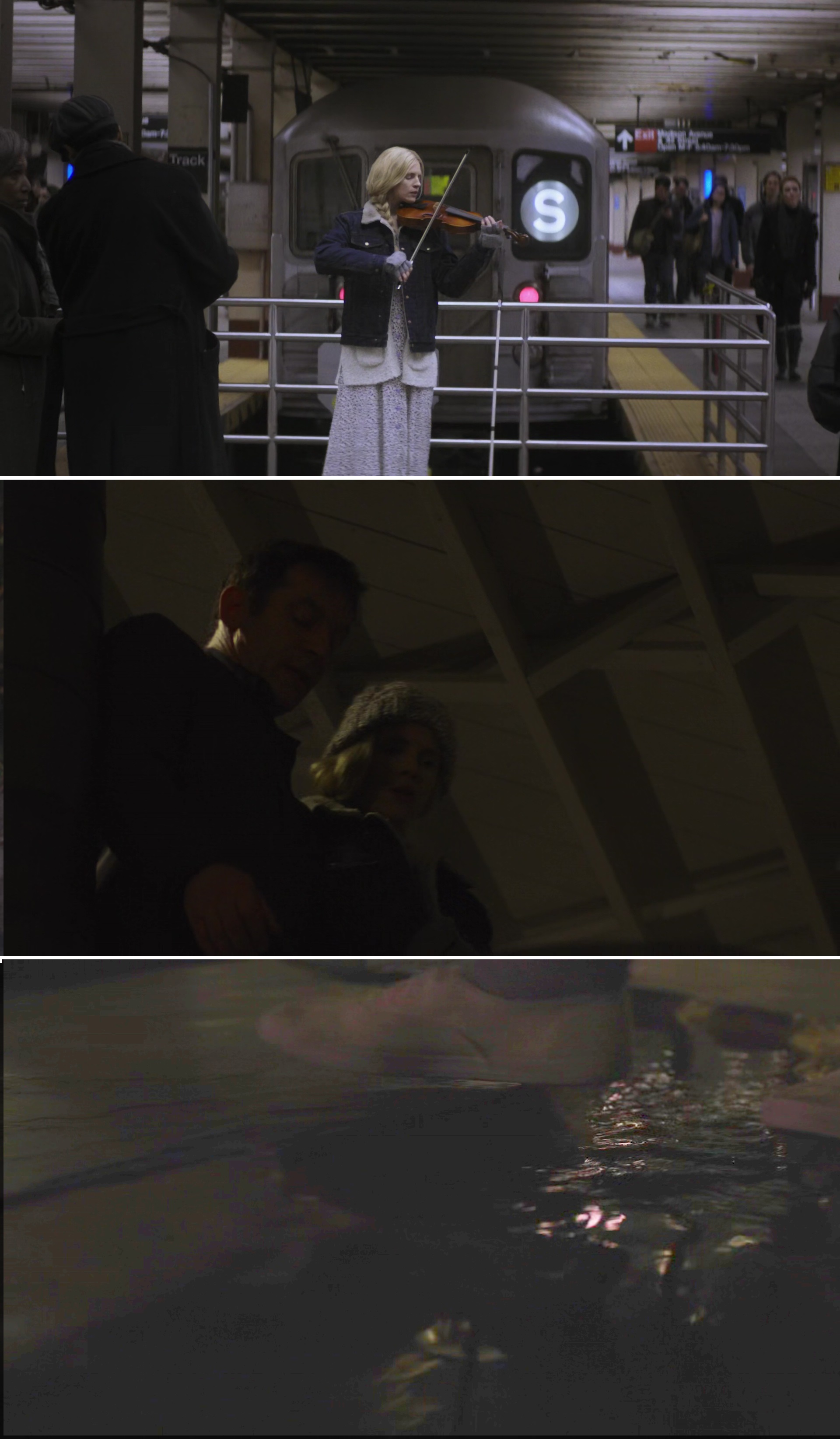

Which leads me to another motif in Chapter 2, one related to the metaphor of the “house” in Chapter 1, which is the use of Underground spaces. Here we get reminded that OA’s father owned a mine, a place from which precious minerals can be recovered. There’s the scene in the New York subways, where Prairie is trying to find her father, only to be found by Hap. And, of course, there’s the “lab” in Hap’s basement.

Which leads me to another motif in Chapter 2, one related to the metaphor of the “house” in Chapter 1, which is the use of Underground spaces. Here we get reminded that OA’s father owned a mine, a place from which precious minerals can be recovered. There’s the scene in the New York subways, where Prairie is trying to find her father, only to be found by Hap. And, of course, there’s the “lab” in Hap’s basement.

In mythology, a journey to the Underground can be interpreted as a journey through the subconscious mind; everything found there is symbolic. Of course the “father” mines precious minerals, if we’re considering the “father” as symbolic of God. Of course Prairie trying to find her father in the subway leads her to her being found by the devil instead. But it’s Hap’s lab that has a motherlode of interesting stuff going on.

Consider our discussion of Water, as a “bridge” from the Ordinary World to the Other Side. Well, there’s a river running through the Lab – and as we’ll see, stepping into a “river” is exactly how OA will describe her intent for the climax of the final episode, not to mention she’s already tried jumping into the Mississippi and drowned outside Moscow. And when she “steps” over the River, I’m reminded of the Colossus of Rhodes, oft described as straddling the harbor of that Island; again, Prairie is likened to Lady Liberty. And it’s down here, of course, that the implications of the “bridge” will be explored in greater detail by Hap and the survivors.

Another detail that stood out are the cross-beams we see on the ceiling as Prairie descends the stairway (to heaven and hell, simultaneously) – they are X motifs, the X indicating a crossing pattern, and Prairie will surely be “crossing over” going forward. It’s down here that Hap describes himself as “lucky” to have found her, which as we discussed earlier is an invocation of his own name. This underground itself smells like “rock,” according to Prairie, to which Hap clarifies that it’s “shale.” Shale is a sedimentary rock that’s a mix of clay flakes and other tiny mineral particles; what makes it “shale” as opposed to “mudstone” is that it has a high degree of “fissility,” meaning it has a high degree of parallel layering – this describes not just the metatextual techniques and aesthetics of The_OA itself at this point, but also the mythology within the show in terms of multiple dimensions and forking paths, which we’ll attend to in Chapter 6.

And of course, there’s the cages themselves, and how the prisoners respond to being locked away.

HOMER: Your thoughts are gonna try to take you down. Don’t let them. You’ll find your freedom. In sleep. In your dreams. It’s how we stay sane.

Homer’s response to imprisonment at the hands of an authority is to withdraw – specifically, he suggests withdrawing into the subconscious mind. It’s a form of checking out, and yet it’ll be an even deeper form of sleep that provides their key to true freedom.

The Five

Speaking of how we respond to systems of domination and control, let’s take a step sideways and consider how the Five are doing, with a focus on French since he’s a bit of a focal character this episode. It’s with French that Buck recaps the Five in broad strokes, and from these broad strokes plus what we’ve seen so far, we can detail five different kinds of responses to the structures of “power over,” and it’s this context that forms the most socially relevant axis of The_OA’s message, though it obviously the subject of “power over” also relates to things like the Gnostic conception of the demiurge.

BUCK: I mean, don’t you think that… she picked us for some reason? Like, Steve’s probably a murderer, and, uh, Jesse’s totally checked out of life, and Ms. Broderick-Allen is weird and sad, and I’m… well, you know.

FRENCH: I don’t need help.

BUCK: No, I know, I wasn’t…

FRENCH: No, I do everything on my own.

Yes, these are broad strokes. But, we have something to get started with. (Many thanks to Starhawk’s book Truth or Dare for the following analysis.)

Steve, who we got to know pretty well last episode, responds to power-over by rebelling. This is a response that’s typified by violent reactions, but our culture is practically predicated on that and as such is much more effective at meting out violence than we are. When Steve responds with violence – punching a hole in the wall, or a kid in the throat, or breaking the law by dealing drugs – he is ultimately putting himself at risk. French nicely points this out to us – “Steve is fucking up his own life,” he says. From this perspective, Steve’s reactions are understandable – he’s responding in kind to his culture, which is not immoral, but rather it’s just terribly ineffective, and generally leads to capture and imprisonment, which is what Steve is threatened by with “Asheville.”

Jesse, on the other hand, is “totally checked out” and based on what a little bird from the future told me, this means he’s doing drugs to withdraw. Withdrawal may seem like a great way to avoid dominating systems, but the problem with withdrawal is that it doesn’t actually change the system at all, at all. And it can often be just as self-destructive as rebellion, though now the dominators don’t even have to flex their muscles; you’re just going to do their work for them. The prison here is of one’s own devising.

So what are we supposed to do? For Alfonso “French” Sosa, the solution is compliance. He avoids the sticks and goes for the carrots that are laid out in front of him. He’s the “good boy” who does what he is told. He gets good grades, writes nice essays, plays sports, helps raise his family – he does everything that’s expected of him. For his compliance, he is rewarded with a scholarship to any school in Michigan. Of course, not only does this not change any of the power relationships with society, it actually reinforces them. No wonder he feels alone.

But let’s take a step back from this analysis and look a bit closer at French before moving on to Broderick-Allen and Buck. We’ll start with his name, as we’re wont to do. “Alfonso” means “noble and ready,” which is exactly describes French’s exterior self and how he relates to the world around him. “Sosa,” on the other hand, is much more apocryphal. It’s derived from the Portuguese “Souza” which is a place name for a particular northern river, but the word itself derives from the Latin saxa meaning “rocks.” So, there’s a resonance here to the Lab underground, which smells of rock and has a river running through it. Finally, there’s the word “French” itself, which indicates the language of France, itself derived from Vulgate Latin – the “common speech” as opposed to that of the aristocracy. So, despite the sophisticated connotations we have today of the French language, it indicates that for Alfonso Sosa that he’s still not really a part of the power structures to which he complies.

But let’s take a step back from this analysis and look a bit closer at French before moving on to Broderick-Allen and Buck. We’ll start with his name, as we’re wont to do. “Alfonso” means “noble and ready,” which is exactly describes French’s exterior self and how he relates to the world around him. “Sosa,” on the other hand, is much more apocryphal. It’s derived from the Portuguese “Souza” which is a place name for a particular northern river, but the word itself derives from the Latin saxa meaning “rocks.” So, there’s a resonance here to the Lab underground, which smells of rock and has a river running through it. Finally, there’s the word “French” itself, which indicates the language of France, itself derived from Vulgate Latin – the “common speech” as opposed to that of the aristocracy. So, despite the sophisticated connotations we have today of the French language, it indicates that for Alfonso Sosa that he’s still not really a part of the power structures to which he complies.

But he tries – of all of them, he actually believes in the system, which becomes apparent in his reverence for doctors. When his little brother sasses back to him about how everything is good except for having a stinky butthole, French replies, “We’ll have the doctor check that out for you.” When his mother gives an excuse (she’s an alcoholic, she is “checked out” much like Jesse) that she can’t go to the boys’ baseball games because she has a “condition” he challenges her with an appeal to authority: “If you really feel like you have a condition, you should let me take you to the doctor.”

And then there’s his reward, a scholarship from the Knightsman Foundation. We noted earlier the resonance to the Knights of the Round Table from Hap’s last name. A “knight” is a man, typically a noble of some sort (remember the meaning of “Alfonso”) who rises to a military rank and is bound to a code of chivalrous conduct – and yes, the Knightsman Foundation has a “character clause” attached to their scholarship; compliance is still mandatory, even with the acquisition of a carrot. But, interestingly, the word “knight” itself derives from the German knecht, which means “servant” or “vassal.” To belong to the Knightsman Foundation, then, is yet another form of imprisonment.

It’s in the scene with French’s mother that we get another taste of power structures, from the Easter Egg newscast that’s playing on the TV to the side of the frame, with the sound in the background:

NEWSCASTER: Saginaw Valley State University will hold its first home football game since a shooting at a nearby apartment complex. There were no surveillance cameras in the area when the shooting happened, but there will be surveillance cameras there this weekend.

So, again, as with Chapter 1, there’s a link between a school and an act of violence. Of more interest to us at this point, though, is that there will be an implementation of surveillance cameras at the scene of the violence. This one of the many ways that system of power-over exercise their power, as we saw in the last episode when the Johnsons remove OA’s bedroom door so they can better “monitor” her, at the cost of her privacy and hence to her freedom.

Anyways, getting back to French, the dynamic between him and his mother is so fraught with tension, and it reveals so much about his character. When he reveals his good news, her first reply is to pointedly ask if he’s given up on Harvard, as if a state school in Michigan weren’t good enough. (French says he can go to Michigan, my alma mater, which is often called “the Harvard of the West,” but it really isn’t.) And, by extension, that he isn’t good enough, that he isn’t living up to his potential. And then she lays a guilt trip on him:

CLAUDELLE: We’ll make it without you. By the skin of our teeth, we will.

French is pulled in two directions at once – he isn’t good enough, because he’s settling for Michigan, and yet going to college will make it harder on the rest of the family. Because, of course, he’s doing so much given his mother is pretty much checked out, too. “You deserve everything and more,” she says, but she won’t give him the one thing he really wants, which is her engagement and participation in raising the family. So he ends up being resentful and judgmental, all part of the vicious cycle of his own isolation. So of course he needs OA, despite his protestations that he doesn’t need help – because he needs to learn how to connect with other people, rather than simply buying into the prevailing power system (which of course tries to atomize and isolate people to begin with).

Finally, before moving on to BBA, we get a look at French’s iPhone. The screen is cracked (which has implications) but we can still see a message from “1ostboy” (who is actually Steve) with pictures of a broken bridge and nearby Russians. “1ostboy” gives us another LOST callout; it can also be a reference to Peter Pan’s “Lost Boys,” boys who end up in Neverland with Peter Pan because they fall out of their carriages and go “unclaimed” (they’re basically orphaned)… and they’re all boys, for girls are too smart to let this happen. I’m less concerned with the faerie tale and more interested in the connection that all of the young adults who follow the OA are boys, not girls.

Finally, before moving on to BBA, we get a look at French’s iPhone. The screen is cracked (which has implications) but we can still see a message from “1ostboy” (who is actually Steve) with pictures of a broken bridge and nearby Russians. “1ostboy” gives us another LOST callout; it can also be a reference to Peter Pan’s “Lost Boys,” boys who end up in Neverland with Peter Pan because they fall out of their carriages and go “unclaimed” (they’re basically orphaned)… and they’re all boys, for girls are too smart to let this happen. I’m less concerned with the faerie tale and more interested in the connection that all of the young adults who follow the OA are boys, not girls.

(That bridge picture is interesting, by the way. First, it’s not literally the same bridge as the one in Chapter 1, so if it *is* the bridge that doomed Nina’s bus, then the text is taking artistic liberties with the information it presents to us in OA’s storytelling. More striking, though, is the implication that the “bridge” between the Ordinary World and the Other Side has been broken, which is far more important I think to the overall messaging of The_OA.)

So, only boys – except for Steve’s math teacher, Betty Broderick-Allen, also known as BBA. Betty represents a more advanced harmonic of French – not only has she complied with the system, she’s moved into a position of authority herself, which allows her to manipulate the system. Which she does, intervening on Steve’s behalf as much as possible. It’s not a bad way to respond to power-over, but it still leaves one compromised. As OA pointed out in Chapter 1, it’s led her to consider the implications of her “job” in providing education to those who don’t really need her at the expense of teaching those like Steve who really do. In this episode, we see her engaged in conversation with Principle Gilchrist, reminding us that she’s still beholden to the power structure. We might be able to manipulate the system, but this still allows the system to manipulate us.

So presented with a system of domination, how can we effectively respond? I think OA is who we’re supposed to think of immediately, but to better understand her position I think we should here consider Buck. Buck isn’t perfect, by any means – in Chapter 1, up in the Abandoned House where Steve is dealing drugs, we see that he’s willing to take Demerol to mitigate his pain, so there’s an element of withdrawal here. And in this episode, he notes that he’s being pressured by his parents to emulate French, the model of compliance. He rejects the rebellion of Steve, and he’s not at a point where he can manipulate any systems.

And yet, of all the Five, he’s the one who I think has most effectively responded to power over, in several important respects – because Buck is someone who resists. Going back to that scene where he finds French leaving the grocery store, Buck is the one who prods French to change his mind and rejoin the Five. He does it not with coercion, nor with logic or any of the tools of the system – no, he appeals to French’s better nature by zeroing in on what really matters, which for French is feeling alone, and Buck offers an opportunity for connection. He points out how everyone is pretty much reacting to the world around them, in less than ideal ways, and though French is at first defensive about this reading, he quickly realizes that Buck has a point – and so French begins (I think) to actively seek healing.

Buck is also the one to assure French that changes can be made in their environment – he asks Steve to stop dealing drugs at the Abandoned House, so French can feel more safe. But this comes at a cost to Buck – Steven won’t be able to get him his testosterone, either, which is a tremendous sacrifice for Buck. Which brings us to Buck’s foundational position of resistance – he is trans. He has rejected the conventional underlying assumptions of gender by claiming an identity contrary to the conditions of his birth. The system of power-over is girded by unexamined assumptions, as it seeks to more or less permanently categorize everyone, with an emphasis on “permanently” because power-over discourages the idea that fundamental change is even possible. This is truly creative resistance on Buck’s part – and it’s not even motivated by a reaction to the system itself, as far as we can tell; people transition because of their interior truths, their invisible selves. No wonder it’s Buck who can turn French around.

Intermission

Intermission

We like intermissions at the Exegesis, even if they come late in a piece. Here we can splice in a few more intertextual references to other media. We’ve already touched on Colossus of Rhodes, so let’s turn to some of the diegetic music of interest here. An easy one is Jim Croce’s “Operator (That’s Not The Way It Feels),” which Hap puts on the record player when Prairie tries to call her parents from his house. It’s just so appropriate, and not just because both Prairie and the singer of the song fail to make their connections.

I’ve overcome the blow

I’ve learned to take it well

I only wish my words

Could just convince myself

That it just wasn’t real

But that’s not the way it feels

While the song is ostensibly about a man trying to get the phone number of his ex-lover, who now lives with his ex-friend (which has nothing to do with The_OA) the song itself is structured ironically—there’s a conflict between the visible self and the invisible self, to use OA’s terms. This has got to be poignant for Prairie, who pretends she’s not invested in her visions, but really is in truth. The song gets another layer at the very end, when Scott echoes what her thoughts likely are upon realizing that she’s been imprisoned, including the desire to believe that this isn’t really happening.

By the show’s climax in Chapter 8, OA will be in a similar position, where she wants to convince herself that something isn’t real, when the truth is that that’s not the way it actually feels. Given that dichotomy, what are we to choose? Embrace the song which comes from inside, the show seems to say, even though it means we have to face the music. This is the Hymn of the Pearl all over again.

OA: If I couldn’t see my father, maybe he could hear me. I would play my violin in the underground until he stepped off a train, heard my song, and came running. And do you know? My plan worked. But it wasn’t my father who found me. It was another man. The man who would change my life.

Music itself has become a recurring thread in The_OA. Nina’s playing the violin for her father, when she’s a child – he says he could pick out amidst a million other musicians. When Hap shows up, it’s because of the music, and it will be again. He tells Prairie that another woman he’s “working with” has perfect pitch – but to Hap, unusual talent doesn’t come from within, no, it has to come from somewhere else. Hap doesn’t actually believe in interiority. Well, he’s wrong. As a little girl, before her NDE, Nina was already accomplished at playing the violin.

Visible self, invisible self. They’re not always in alignment, but just because the invisible self isn’t visible doesn’t mean it doesn’t exist if there isn’t an objective “place” from which it emanates. To acknowledge the invisible self, then, is in some respects a matter of faith.

PHOTOGRAPHER: All right, everybody, relax. Looking good. Prairie, my dear, toward the sound my voice. Prairie? Prairie, toward the sound of my voice, honey. Yeah, there you go.

Sound of my Voice was the first movie by Brit Marling and Zal Batmanglij, the writers of The_OA and the performer and director, respectively, of both works. In Sound of my Voice we follow Peter and Lorna in their quest to expose cult leader Maggie (played by Marling) as a charlatan—shouldn’t be hard, given she’s claiming she’s from the dystopian future. There’s a lot of cliché cult tropes in the film, like the cult members wearing white clothes (think the Guilty Remnant from The Leftovers) having an elaborate secret handshake, and of course a bevy of emotionally manipulative group exercises to create communitas within the cult.

Maggie eventually approaches Peter, who is a substitute teacher in his day job, and asks him to bring one of his eight-year-old students to meet her; Maggie claims she’s actually the daughter of the little girl. Peter is willing to comply, because he doesn’t want to get kicked out of the group. Lorna, however, is approached by government agent hoping to capture Maggie; the meetup of Maggie and the little girl is where the sting will happen. Maggie meets the little girl, but then does something so stunning that all of Peter’s skepticism is thrown into doubt—perhaps Maggie’s story of being from the future could actually be true. Maggie, though, is captured and dragged away, and the film ends.

The audience is left with the ambiguity, and has to determine its own take on the narratives given—was Brit Marling’s character actually telling the truth? Or will they believe in the authorities? Marling and Batmanglij, then, have done this trick before The_OA, that the ambiguity is deliberate—the whole point is to get the audience to make a choice. As such, there’s more active engagement and participation required of the audience than when there’s no narrative ambiguity; we become co-creators of the text.

Given our discussion of power and authority, I would hope it’s clear what the “answer” to these texts most pointedly is not.

Oh, but if only we had some kind of device that we could actually listen in on the interior and discern the heart of the matter! Well, this is exactly what Hap is trying to do. He wants to the be the authority, he wants there to be no doubt… and no choice. Right now, death is the ultimate ambiguity. If ambiguity entails choice, then might not death be the opportunity for making the ultimate choice as well? This is what the consequence of Hap’s work would be.

Oh, but if only we had some kind of device that we could actually listen in on the interior and discern the heart of the matter! Well, this is exactly what Hap is trying to do. He wants to the be the authority, he wants there to be no doubt… and no choice. Right now, death is the ultimate ambiguity. If ambiguity entails choice, then might not death be the opportunity for making the ultimate choice as well? This is what the consequence of Hap’s work would be.

OA is on the other side. “I hear your heart beating,” child Nina says in the beginning. “Don’t be afraid. I know you are a good snake.” She doesn’t actually know this, of course, but by having the choice to believe this, she changes how she relates to her environment, for better and for ill, but always true to herself.

I don’t mean this to be an essay on CPR (I’ll leave that to French) so let’s turn to the song that’s playing on French’s iPhone after he snorted some coke to keep himself going after his all-nighter. The song is “Full Circle” by The Haelos. Ah, now we’re on firmer ground!

We’ve come full circle

We’ve come full circle

Like a serpent coiling no end

Just the same mad circus

Wait

For blood to blossom

The saints and soulless to mend

Like we’ve all forgotten

Again and again and again

In the previous essay, we brought up a number of circular references – Homer’s statement he’ll come away with a championship ring, and subtle nods to LOST and Battlestar Galactica – and speculated on whether there might be a thread of “Eternal Return” buried with The_OA. (I should have also brought up the ending to Strangers on a Train, which takes place on a carousel that spins out of control.)

I feel more confident about such speculation after this episode, first and foremost from this song. It’s trancey and repetitive, and of course the lyrics are resoundingly circular – the “serpent coiling to no end” doesn’t just echo the snake that Nina handles at the beginning of this episode, it is of course The Ouroboros, a Gnostic and Hermetic symbol as well as one prevalent in Alchemy, a snake biting its tail symbolizing the endless cycle of death and rebirth, creation and destruction – in other words, change and self-recreation. It connotes the interconnectedness of everything, a circulatory process (hence the emphasis on the heart in this chapter) whereby the integration of opposites can be achieved: “one is the all.”

All this has happened before, and all this will happen again. It’s like the Russian Nesting Dolls that Nancy finds in the bathroom, it’s dolls all the way down; as soon as the invisible self becomes visible, a new invisible self inevitably fills the resulting void. And this sense of recurrence fits nicely with The_OA’s aesthetic of repeating symbols and situations.

Windows to the Soul

Windows to the Soul

So let’s get this wrapped up. One last motif to explore, and one that’s compellingly presented at the beginning and the end of this episode. Well, almost at the beginning. As we said before, the first image of New Colossus is a picture of Liberty’s eyes, under water. Then we cut to Nina’s face, and pan down to the snake she’s holding. We soon see that there are five blind children in the classroom, and each has a glass tank in front of them to hold their snakes. The tanks are arranged in a pentagon.

OA, of course, has found Five people to tell her story to.

At the end of the episode, Prairie becomes trapped in a cage of glass, along with three other people. Not quite five… not yet.

So there’s a metaphor here, and it has to do with glass, with windows. Glass is much like Water – it’s translucent, and it’s a reflective surface. But water is soft, and vital to life. Glass is hard and unyielding. You cannot touch someone through glass – not the visible self, at least. If “Water” is metaphorically a “Bridge” in The_OA, then Glass is its antithesis. The Bridge is a connection. Windows, on the other hand, prevent connection. They represent a lack of connection. Only the image of the visible self can pass through glass. And here, glass literally becomes a prison.

This is actually something that the show started to establish in Chapter 1. When Steve’s girlfriend leaves, rejecting any kind of a relationship with Steve, he’s framed by a big glass window as he looks out to see her disappear; he then punches a hole in the wall. At school, Steve is disconnected from BBA and the classroom, and gazes out the window disconsolately; only when she winks at him does his gaze move away – and ours, as the camera shifts to show him with a giant eagle in the background, and no windows in the shot. When OA comes home to Crestwood, she’s separated from the neighborhood by the car windows; she doesn’t have any connection to this place, and literally has to cover herself up to get inside the house. And when OA is making a video recording of her Dollhouse, she lingers at the window briefly, and the faintest of reflections can be seen; at this point, she is isolated from the rest of the world, and quite likely herself

Likewise, then, passing through a window indicates connection, or an attempt at connection. Steve climbs through OA’s bedroom window, for instance, in Chapter 1, and this indicates that he’s accepted OA after the dog incident at the Abandoned House. He brings her a router, which gives her connectivity to the Internet. In Chapter 2, the moment that French relents to keep going to OA’s sessions, he rolls down his car window so he can tell Buck that he’ll drive them there.

Hap tries something similar with Prairie up in the airplane:

HAP: Put your hands to the right. There’s a window there. Pull it. Okay, slide it down and back. There’s a latch in the middle. Keep going, there you go, and pull it up and over and back. Up and over and back, all the way. Push the window. Push, go on.

Prairie’s hand slips through the window, and she literally touches the clouds. Which is a metaphor for Hap’s true intentions, unfortunately, not to mention that this brief sense of connection is a way to hide the truth of his home, which is a prison. It’s cold outside the plane, that’s what she’s really touching, and that’s what she gets at Hap’s, which has “insulated glazing on every window” because “the winters are brutal.”

So when we see Nancy espy OA out the bedroom window after her late night sojourn, it doesn’t bode well — and this after Abel said Nancy’s eyes were sparkling after making love! In the very next scene, Nancy is so afraid she wants to lock up OA in the house, or have her committed. This reading of windows also gives us a new perspective on Prairie’s dream of her father at the Statue of Liberty. When she finally sees him, up in Liberty’s crown, we see the crown’s windows lined up behind her. What a juxtaposition of freedom and imprisonment! Which is exactly what her fate turns out to be.

Finally, let us reconsider the repeated images that frame this chapter. The snakes are put inside the glass tanks. The NDE survivors are put inside glass tanks. Now, snakes have gotten a bad rap in Western mythology, what with the Temptation of the apple of knowledge from a World Tree in the Garden of Eden. And yes, as Scott suggests at the end, everyone in Hap’s basement made choices, led by temptation, to get themselves there. But as we heard from the song on French’s iPhone, you know, the one with cracked glass, the snake also represents coming full circle, eternal return, an integration of opposites… something Divine. So it goes for OA and the people she meets in the Underground.

Reach out and touch your screen.

Remember. You know who you are.

Sssssssss.

February 21, 2017 @ 8:51 pm

Pearls also makes me think of the medieval poem “Pearl” in which the a bereaved father has a dream-vision of his beloved daughter across a river (death) and asks her questions about the afterlife. By the same poet as Gawain and the Green Knight, another connection to Arthurian knights.

February 21, 2017 @ 10:37 pm

Nice!

February 24, 2017 @ 10:41 am

Nothing really to add here Jane but I can’t let your comments be overtaken by trawlbots.

Episode two was when I began to realise that this drama was not going to follow a conventional ‘superheroes journey’ and would be all the better for that. I think the most disturbing aspect throughout the season is the revelation of OAs adoptive parents as being less than perfect. Martha and Jonathan Kent they are not. Consequently the ‘adopted child discovers hidden powers despite disability’ narrative is detourned and the text neatly sidesteps the potentially problematic ‘magic blind person’ trope.

March 15, 2017 @ 11:36 am

The inspection phase will be an eye opener to you and will empower you to establish if the market has what you are looking for in the range to buy. So, this is how to buy Classic Mercedes For Sale. In such situations the loaning authority stays with no choice yet to repossess the vehicle and also obtain it in a sale to ensure that the impressive equilibrium can be raised. It will be of no use to halt your searches in other markets basing on a sale that does not have the kind of a car that you are looking for. Pop over to this web-site http://www.heritageclassics.com/ for more information on Classic Mercedes For Sale.

Follow Us: https://goo.gl/0HARSc

https://goo.gl/rTQHZU

https://goo.gl/vUy9hM

https://goo.gl/8QWKNx

https://goo.gl/RAeB4F

October 19, 2017 @ 9:11 am

The information you share is very useful. It is closely related to my work and has helped me grow. Thank you!

April 2, 2020 @ 4:23 am

23isback https://23is-back.com/ 23isback

June 4, 2020 @ 9:57 am

Fully enlightening article! This is incredibly a reasonable article I need to express your article is great since you are intertwined

different sorts of a historic point with a remarkably supportive data in have blog. Truly I energetic to look at your blog.

http://www.gammatech.org/