An Increasingly Inaccurately Named Trilogy: Episode IV – A New Hope

Coming at A New Hope off of the prequel trilogy, what jumps out first and foremost is how much smaller and more intimate a story it is. No small part of this is because of the twenty-eight year backwards jump in film technology, which isn’t something that can be erased even by Lucas’s extensive efforts to tinker with the original trilogy. Which I suppose are a digression worth getting into at this point.

Coming at A New Hope off of the prequel trilogy, what jumps out first and foremost is how much smaller and more intimate a story it is. No small part of this is because of the twenty-eight year backwards jump in film technology, which isn’t something that can be erased even by Lucas’s extensive efforts to tinker with the original trilogy. Which I suppose are a digression worth getting into at this point.

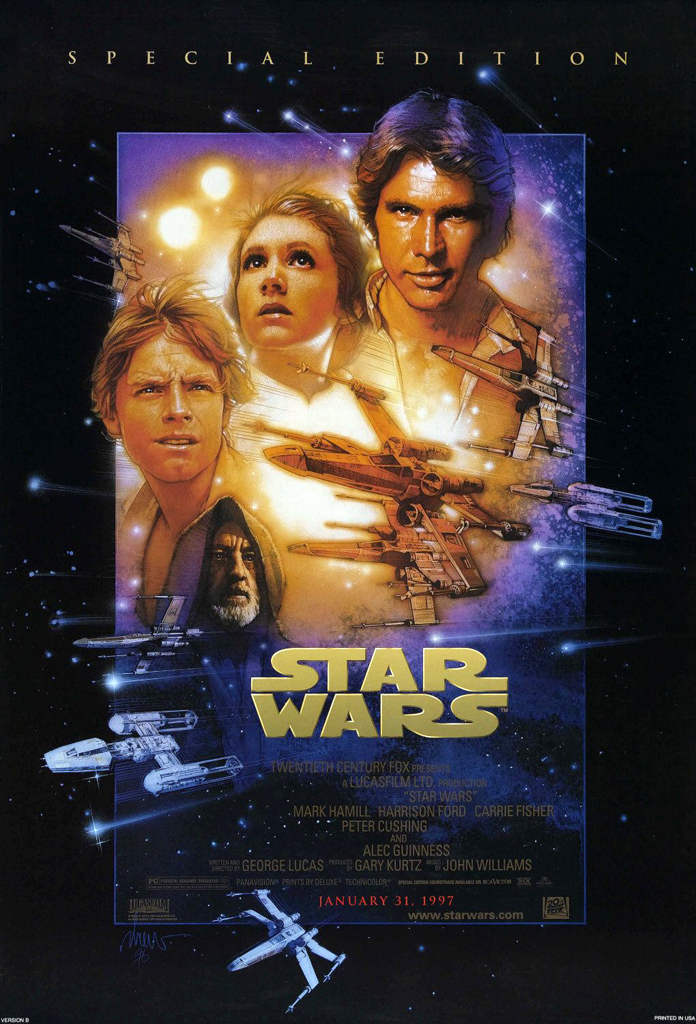

Obviously the special editions are easy to get cranky at. Hell, I’m on record making fun of the “redo old special effects for the DVD release” approach when it comes to Doctor Who. And the scholar in me is unsurprisingly appalled by Lucas’s active efforts to suppress the original theatrical versions of his films, to the point of denying film festivals focused on the 1970s permission to screen an original print. But these days there are multiple gorgeous reconstructions of the theatrical version up on BitTorrent for people who care, and while that doesn’t invalidate the understandable frustrations of people who spent decades wanting to watch the movie of their childhoods and not a CGI-ed over mess where Greedo shoots first and there are a bunch of cavorting aliens around Mos Eisley, it at least makes them a somewhat easier pill to swallow.

But the bigger difference between the special editions and replacing a dodgy puppet snake with a dodgy CGI snake in Doctor Who is that if you’re watching Doctor Who for its visual spectacle you have already fucked up. Whereas Star Wars has always been about raw visual spectacle in a way that makes the original trilogy’s aging into a problem for them. Without wanting to get into a (desperately tedious) debate about the superiority of traditional special effects vs CGI, it’s on a basic level understandable that Lucas would want a reaction to A New Hope other than “well that’s dated.” A uniform style of special effects across the saga is an entirely sensible desire when the saga is going to be presented as a single unit. So long as the actual historical objects are preserved in some fashion – and I’m fine with that fashion being BitTorrent – I can at least see the sense of trying to give a six-part film series a unified design.

No, the problem is simply that, as I said, you can’t actually bridge that gap. Lucas can and did narrow it, and it’s certainly less jarring to watch the special edition of A New Hope after Revenge of the Sith than it is to watch one of the restored theatrical versions, but at the end of the day A New Hope feels like a fundamentally different kind of object from any of the prequel films. It follows only a handful of characters, never moving wider than those caught in the immediate consequences of Leia’s ejecting R2-D2 and C-3PO onto Tatooine to find Obi-Wan. To its original 1977 audience, this basically appeared to be a film about a single space station.

But, of course, coming off of the prequel trilogy the scope of it is not so much “a single space station” as the moment, some twenty years after Revenge of the Sith, where Anakin is reunited with his two children. More than perhaps anything, this is the defining decision of the film. It would have been entirely possible, and arguably saner storytelling, to do the prequel trilogy such that the first film essentially combined the storytelling duties of The Phantom Menace and Attack of the Clones, the second film did Anakin’s fall, and the third actually took place during the ascendency of the Empire. Instead Lucas decides to make the saga about the Skywalker lineage, deciding that all the events that take place between Luke and Leia being spirited away and the reunion at the start of A New Hope can be relegated to the spin-offs.

There’s only one colossal problem with this, which is that none of the three characters involved in the reunion actually know the reunion is going on. This thus ends up being something of a farce without actual comedy – three characters the audience knows far more than bumbling around and failing to get to the actual plot. The only character with any agency ends up being Obi-Wan. (R2-D2’s knowledge of the prequel trilogy is difficult to actually square away with what’s on screen here; on the whole everything makes much more sense if one assumes he also had his memory wiped along with C-3PO, although that’s pretty clearly not the intent of Revenge of the Sith and the continuity lapses can be squared away by other means. Certainly it’s easier than figuring out why Vader doesn’t point out that he literally just chased Leia from Scarif when she tries to claim she’s on a diplomatic mission.) And frankly, Alec Guinness doesn’t play the scene where he lies to Luke about Anakin as Obi-Wan lying, largely because when he played it nobody actually knew that he was lying, Lucas having not settled on the “Vader is Luke’s father” twist until nearly a year after the film was released. It’s plausible, due almost entirely to the fact that Alec Guinness is actually incapable of playing a role without ambiguity and nuance, but it’s clearly not the intent of the scene as shot. And the Obi-Wan/Vader lightsaber duel is flatly impossible to read as consistent with the prequel trilogy (or indeed with The Empire Strikes Back) – there’s simply no way to imagine the Obi-Wan we’ve spent three whole films with calling Anakin “Darth.” And so as a payoff to Revenge of the Sithi, A New Hope is understandably a complete failure.

Meanwhile the things the film is actually invested in – Luke’s quasi-classical Hero’s Journey – are largely obscured by the prequels insertion in the narrative. Luke isn’t exactly a character long on depth or nuance, which is fine when the world of Star Wars is new and things like the sudden rush of weird aliens in the cantina scene serve as an actual expansion of scope. He’s a perfectly functional viewpoint character. But as a protagonist defined primarily by being Anakin’s secret son, well, it’s hard to figure out why the film isn’t spending more time on the self-evidently more interesting and equally mythos-rooted Leia. The answer isn’t hard to figure out, and Carrie Fisher would have been happy to spell it out for you, but, spoilers, it’s a deeply unsatisfying one.

The hilarious and mildly trolling endpoint of this argument would be to suggest that A New Hope is thus inferior to the prequels, and it’s deeply tempting. But it’s also ridiculous. More than anywhere else in the saga, that makes this the film where our approach encounters its limits. Imagining The Phantom Menace as someone’s first exposure to the franchise is one thing. Imagining that this film is actually Episode IV and called A New Hope is quite another. This is Star Wars; the only film that can legitimately be called simply that. It’s a metonym for the entire saga. Much like one cannot hear the Imperial March as anything other than itself, the knowledge that A New Hope is the beginning is inescapable.

If one bludgeons through this tension, insisting on inventing a viewer completely incapable of understanding that this was made before even the barest phantom of the prequels was imagined but who is nevertheless an intelligent and discerning viewer, the reading eventually resolves into a film that is about introducing the galaxy after the Empire has completely taken hold. In this regard, the line about the dissolution of the Senate clearly positions the twenty year gap as not just a product of the Skywalker diaspora but as a precise bridge over the rise of the Empire. Indeed, this finally makes some sense of the Yoda/Sidious duel that wrecks the Senate chamber, which is a logical anchor opposite the Senate’s actual and final dissolution. It’s something of a pity Lucas didn’t have the audacity to cut in a Jimmy Smitts evaporation scene, especially in light of Rogue One, but this still basically works.

Except that the intimate scale of A New Hope means that the imperial galaxy is introduced almost entirely in terms of Tatooine. Which on the whole seems… nice. It’s tough to tell, since it appears to consist of nothing save for Owen and Beru’s farm, but one thing becomes staggeringly conspicuous in its absence: slavery. Even when Jabba shows up, providing a direct connection to the gangster regime that oversaw Anakin and Shimi’s enslavement, he appears to have moved into the spice trade. And with no real sense of other planets, the result is to suggest that for all its evident brutality the Empire has actually improved life in the galaxy.

But this is hardly the first instance of muddy politics in the saga, so let’s carry on. We already briefly discussed the way in which the cantina scene serves to open out the world within the film’s conscious structure, but in the context of illustrating the differences between this world and the one of the prequels there’s a more obvious aspect of it than the cool alien design: Han Solo. Ultimately, no character even remotely like him exists in the prequels. For all that the prequels have bounty hunters, corrupt businessmen, gangsters, and Sith Lords, all of the main characters are agents of legitimate governmental authorities. Han Solo, on the other hand, is a criminal; a character with an oppositional relationship not only to the fascist empire but to all governmental authority, the defunct Republic included. He’s also self-evidently the most charming and entertaining thing the saga has yet presented.

Han is not, obviously, the first charming rogue in genre fiction; this is as well-worn a trope as space monks or laser swords. But save for a handful of scenes in Attack of the Clones the sort of worldview he offers simply doesn’t exist in the prequel trilogy. He represents a fundamentally new idea. And it’s one that finds a close cousin in the other new idea the film introduces: the Rebellion. Indeed, this is the one regard in which the prequel trilogy might credibly be said to enrich A New Hope itself. As it stands, the sudden expansion of scope very late in the film whereby the Rebellion is introduced is a jarring tonal shift – a hodgepodge of new characters who are largely indistinguishable from one another and an unexpected genre pivot into “war film” that is poorly set up by the first 75% or so of the film. It’s a minor complaint, to be sure, but a real one that comes out of Lucas trimming some early Tatooine scenes that served as setup by establishing Biggs as an existing friend of Luke’s in order to make the opening pacier. (It’s a sound decision – the scene is a clumsy bit of political exposition that makes the Senate scenes in The Phantom Menace look like The Lion in Winter.)

But coming off of Revenge of the Sith, the confluence of Han Solo and the Rebellion offers the resolution to the Republic/Empire dialectic: anarchism. Obviously this exists within the fundamentally compromised politics of the saga, which is no more straightforwardly anarchist than it is anti-fascist. Nevertheless, it’s on the whole a good fit. One of the biggest differences between the original trilogy and the prequels is their focus on constructive politics. The prequels are regularly concerned with the affirmative question of what government should look like. The original trilogy, on the other hand, does not touch the question of what the Empire might be replaced with. It’s simply not something that was part of their conception. They’re about the Rebellion, not the Republic, with all that entails.

Positioned after the prequels, however, the question becomes unavoidable. Rebellion becomes not an alternative focus to constructive democratic institutions but a replacement – a step forwards in whatever political argument the saga is making. And it’s largely Han Solo that forces the issue, for the simple reason that he would not have fit comfortably under the Republic either. As the one thing in A New Hope that is in no way set up by the prequels, he immediately assumes the vacant role of moral viewpoint character for the saga. Which is by some margin the most interesting choice made so far.

Ranking

- A New Hope

- Attack of the Clones

- The Phantom Menace

- Revenge of the Sith

February 20, 2017 @ 2:33 pm

As a lifelong Star Wars fan (you might say it was my “native mythology” mashed up with Doctor Who as a child, to paraphrase Lawrence Miles) this series is really enthralling me. But its also making me a bit sad in that… Man the level of quality of analysis of Star Wars over the years really has been lacking, hasn’t it :/? Its a bit depressing. This is legitimately some of the best stuff I’ve read ever on the series, and that shouldn’t be the damn case.

I know you’re not going to, but it does make me so curious what a Tardis Eruditorum esque take on the Clone Wars/Rebels shows would be like. If I ever start up a Patreon and can find a home for it, I might very well try to take it on myself in the future. The Clone Wars show is great, surprisingly great, and probably the most accurate picture of how George Lucas really imagined the Star Wars Universe. Weirdo vision planets and all.

Also, RE: Han Solo. He definitely is a character who gets even better thanks to the contrast of the prequels, something that gets overlooked now yeah…

But also notable is how the “Emperor has dissolved the Senate” line is so much more poignant now. Its casualness is part of its power. Of course the fascists offhandedly kill Representative Democracy. Now onto other business.

February 20, 2017 @ 2:40 pm

“he immediately assumes the vacant role of moral viewpoint character for the saga. Which is by some margin the most interesting choice made so far.”

Something that Firefly/Serenity would then pick up and run with.

February 20, 2017 @ 4:01 pm

Not to be anal, but surely Blake’s 7 ran with that torch first? And Blake’s 7 is also the model for Firefly, not Star Wars (occasional “they’d be crazy to follow us” joke aside).

February 20, 2017 @ 4:51 pm

Haven’t seen Blake’s 7, so can’t really comment on whether it and Firefly share elements, but it seems peculiar to suggest Firefly/Mal therefore couldn’t have been modelled on Star Wars/Han…

Also according to this, Whedon’s never seen Blake’s 7: http://io9.gizmodo.com/the-real-reason-why-joss-whedon-named-his-space-western-1614273050

February 24, 2017 @ 2:43 am

Whedon has said that Firefly was inspired by imagining the Civil War era crossed with life aboard the Millennium Falcon, see this interview:

Also, there’s a rumor that another element of the inspiration for Firefly was the old roleplaying game Traveller, see here.

February 20, 2017 @ 3:55 pm

this has been a great series, Phil. & yes the condundrum of trying to reconcile the first, founding Star Wars movie with its canonical “fourth” position is near-impossible at times (another minor nit—why doesn’t Vader ever say, ‘huh, Tatooine. I know that world. Why don’t you look here and here, and talk to this guy” when the stormtroopers are looking for the droids?)

but the biggest disjunct is how the original movie at the time made the past seem much more distant, not a 20-year gap. the Clone Wars, the Jedi, the Force all seem to be from another long-lost world, like talking about WWII to a kid in 1977. perhaps you can say it’s how fascism moves so swiftly at times that it makes the recent past seem suddenly far away.

another thing Rogue One did to complicate matters was to make the Rebellion very aware of the destructive power of the Death Star, and how it was essentially an endgame situation–they had to destroy it ASAP or they were done. in the orig. SW, they still seem to have only a murky idea about it & you get the sense the attack-the-death-star gambit is just one option—that they might’ve tried something else if the plans hadn’t come through.

February 20, 2017 @ 5:19 pm

Only a 30 year gap in 1977– like the eighties to us now

February 20, 2017 @ 6:32 pm

In fairness, most of the rebels who recognized the threat of the Death Star and saw it in operation were dead by this point, and of the rest, only Leia is on the moon of Yavin. Given what happens on Hoth later, the rebels seem to naturally gravitate toward evacuation over confrontation with a lot of good reasons to do so. The Death Star as existential threat becomes clearer later, especially when word comes that the Empire is constructing a second one (which will presumably fix the flaw in the first).

I can actually buy Vader a lot more after Rogue One: he’s in hot pursuit, he’s especially mad at the situation (explaining why James Earl Jones yells so much more in the early scenes), and there’s no indication that he knows they’re in orbit of Tatooine. In fact, he sends troopers after the escape pod while jumping his ship back to the Death Star to join Tarkin. He’s obviously more concerned with using Leia to find the rest of the rebels, and why not? Kill the rebels and there’s nobody to smuggle the plans to!

You can clearly see that things like data security (or even easy data duplication) simply aren’t factors in this film.

A nice reading here, one that plays against Phil’s aside that we encounter no slaves in ths film, is that because the Empire (and the Republic before it) consider droids to be objects or property, nobody seems to consider that droids were in the escape pod and could abscond with the plans. This Imperial disregard, coupled with their disregard of small fighters and of surprise smuggler attacks, stems from the same sources that produce the inequitable and often insufferable social conditions in the prequel films.

Which in turn plays into Phil’s anarchist reading. What brings down the Imperial war machine isn’t a galaxy-striding hero, but rather the grit in the machine, the little people the Empire never considers. Of course Anakin doesn’t like sand.

February 21, 2017 @ 7:24 am

It’s literally little Little harmless-looking teddy bear people that help destroy the second death star.

February 20, 2017 @ 5:16 pm

Also Uncle Owen and Aunt Beru were lying through their teeth

February 21, 2017 @ 2:06 am

What’s really strange watching these in order is how the clones just disappear from the plot. The building of the clone army is the central mystery and moral conundrum of the second film, the clones wipe out the Jedi in the third, and then…nothing. We get an offhand mention of the Clone Wars in the fourth one, and that’s it. No more clones.

But if we’re watching A New Hope directly after Revenge of the Sith, with no outside knowledge of Star Wars, we might think otherwise. The EU doesn’t support this, but as far as our hypothetical, cave-dwelling, first-time viewer can tell, the stormtroopers in A New Hope are clone troopers, or at least a model of clone trooper. They wear similar white armor, are known only by their alphanumeric designators, and have a distinctive physical build (“Aren’t you a little short for a stormtrooper?”).

If we watch the prequels with this in mind, it looks like the political decline of the Republic tracks with the moral decline of the Jedi, who go from ignoring slavery to industrializing it to being replaced by it. Fittingly, Darth Vader, the last surviving, active Jedi, has been reduced to a glorified stormtrooper, a manufactured being who wears humanity-concealing armor and serves the will of the state.

The Jedi, like so many of their real-world counterparts, never come to terms with how their tolerance of injustice led to the rise of their enemies. The Republic is “a more civilized age,” the Clone Wars are an “idealistic crusade,” Darth Vader “turned to evil.” They tell themselves that the Republic was a better world undone by bad people doing bad things…and because it was a better world undone by bad people doing bad things, at least in part, the simplified narrative is easier to swallow.

February 21, 2017 @ 2:11 am

Sorry about the italics.

February 21, 2017 @ 5:46 am

I know there’s at old bit of SW errata from I wanna say around the time that ESB came out that outright explained the Stormtroopers as specimens grown in a lab, incapable of individual thought (notably, not labeling them as Clone Troopers, but implying them to be something altogether distinct from the vague idea of the Clone Wars).

Personally I’ve always found that to be a load of rubbish, if only because there’s absolutely no sense within the original film that the Stormtroopers aren’t just regular people–certainly it becomes hard to square away their chatter when Ben is traipsing about the Death Star.

February 21, 2017 @ 9:53 am

Of course, I standby the idea that A New Hope is worse than the prequels, by the simple virtue of being more boring.

February 21, 2017 @ 3:53 pm

I’ve made a similar argument in the past:

The plot of “The Force Awakens” is so similar to “A New Hope” as to basically be the same film. Thirty-something years have brought massive improvements in CGI and graphics, so TFA looks much nicer (a bigger budget doesn’t hurt). There’s more than one woman in the entire cast of TFA, and not everyone is lilly white (despite growing up on a desert planet with multiple suns, hmmmm). The back story of TFA is much better thought out because it’s not just being made up by Lucas as he goes along. etc etc.

So, for these reasons and more, The Force Awakens is a better version of Star Wars.

(After I have made this argument I usually duck and hide)

February 21, 2017 @ 10:32 pm

I mean, I think TFA is an almost disgustingly cynical cash grab… that is also very boring. A New Hope is boring, but it’s groundbreaking and daring and new. The prequel trilogy- massively flawed, often boring, incredibly misguided- still trying to do something, to say something.

TFA was made with the single mandate of ‘don’t fuck it up’. And I guess they didn’t. But good lord is it a boring film.

February 21, 2017 @ 10:41 pm

I think there is something here to be said about the fact that although the films are meant to form a single saga, they’re still two separate trilogies. A New Hope doesn’t follow directly on from Revenge of the Sith anymore than Rose follows on from Survival. There’s a gap in-universe and out.

I think, in a six film saga, there is merit in the film taking the space to introduce the new cast before drawing the threads together once more. The payoff to Revenge of the Sith was always going to be Return of the Jedi.

February 22, 2017 @ 4:58 am

It is simply impossible to attempt to reconcile Star Wars (that was what it was called when I saw it in 1977, and that’s how I will eternally think of it) with the prequels for the most obvious of reasons:

It wasn’t part four of anything when we first saw it. The backstory that was hinted at was not the backstory we got.

There’s a telling moment in one of the Timothy Zahn books that relaunched the Star Wars universe as novels that shows how people viewed what little backstory Lucas gave: one plot point is the discovery that the Empire has gained access to cloning technology and is about to start…wait for it…cloning stormtroopers. Something the Empire had never done.

So, yeah. Trying to analyze these movies as six films with the putative fourth film leading from the third would be easy to do, had Lucas bothered to write three movies that, you know, actually did that. You can’t convince me that in 1977 Lucas meant that the Clone Wars were “the Republic using an army of clones against an army of droids”, any more than “When I met your father, he was ten years old.” The effort is applauded, but it seems odd to even try.