This Nightmare Would Have Ended (Heaven Sent)

|

| I got a rock. |

It’s November 28th, 2015. Justin Bieber continues his assault on the top ten, holding number one with “Sorry” while “Love Yourself” and “What Do You Mean” are also in the top ten. One Direction and Nathan Sykes also chart. In news, a gunman attacks a Planned Parenthood clinic in Colorado Springs and Turkey shoots down a Russian jet on the Syrian border, sparking a bit of an international incident.

On television, meanwhile, Moffat’s masterpiece. Which means that we should start by talking about Blink, the story to which any supposed Moffat masterpiece must be compared. It is not that Blink is straightforwardly and unquestionably the best Moffat story; picking The Pandorica Opens/The Big Bang or Day of the Doctor is an eminently respectable choice. But a masterpiece is different from a mere best, implying not just raw quality but a sort of technical proficiency that shows off the writer’s skill. This is why Blink serves as the type specimen for Moffat—a story long on formal constraint and ostentatiously clever structure that plays elaborate games with time and causality. Its ostentatious grandeur hangs over the whole Moffat era, a high watermark whose reputation seems to foreclose the possibility of ever topping it.

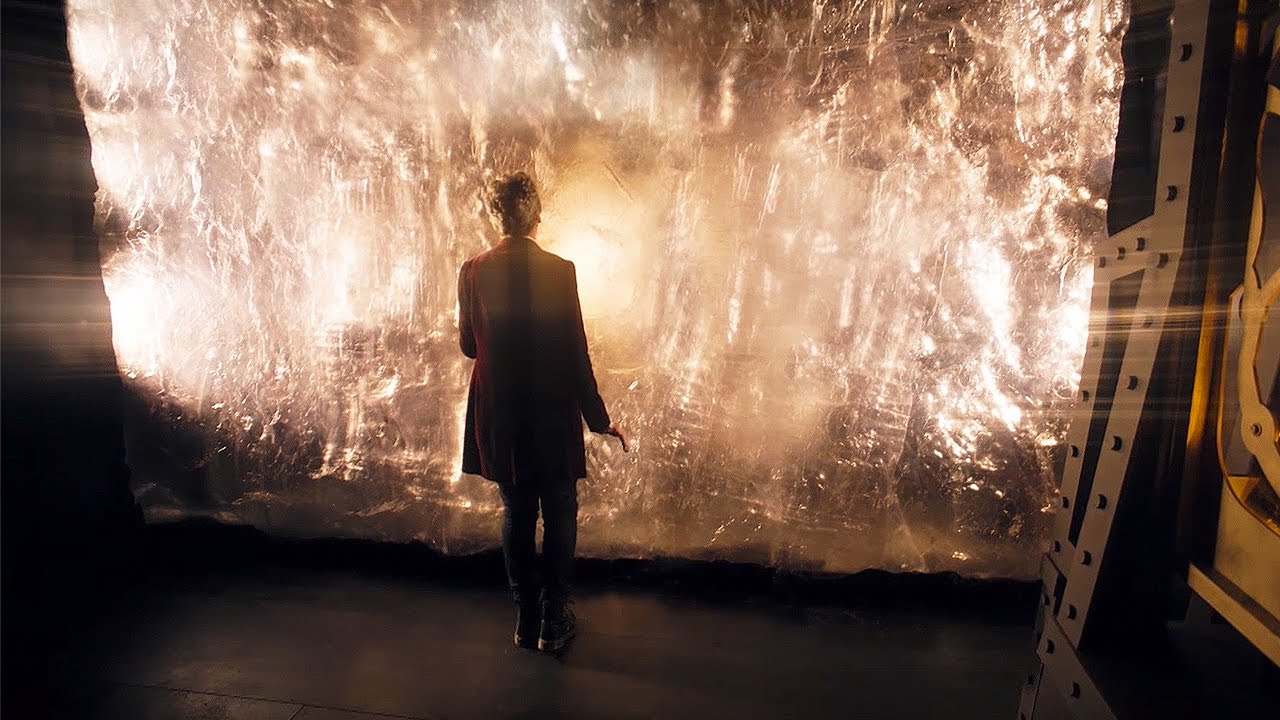

And yet Heaven Sent brazenly tries to. This is clear from the basic technical premise: a one-hander, in which Peter Capaldi is left to carry an entire fifty-five minute episode by himself, with no co-stars save for a silent monster, a cameo by Jenna Coleman, and a young boy with no dialogue in the cliffhanger. Where Blink was a doctor-lite episode, Heaven Sent is its radical opposite, an episode that is not so much Doctor-heavy as it is Doctor-exclusive. There’s an almost petulant quality to the anxiety over self-plagiarism, a sense that in going to the opposite extreme Moffat has only confirmed the validity of the comparison. But what is perhaps more telling is the nature of the technical challenge laid out. Blink existed because of a scheduling challenge, minimizing the Doctor’s appearances so it could be double blocked with Human Nature/Family of Blood, Heaven Sent is a one-hander for no reason other than to be impressive. It’s not a clever solution to a production problem; it’s clever because the show wants to be appreciated for how clever it is.

Is this arrogant? Narcissistic? Self-congratulatory? Yes, of course it is. There is no point in pretending that Heaven Sent is not an exercise in vanity that seeks to put a final and decisive triumph on Moffat’s record before he departs. That it unequivocally succeeds does not change the task in question. But we’ve kind of buried the main point in all of that. Heaven Sent is a story that only makes sense in the context of Moffat’s presumptive departure. Its presence in the season is a crystal clear sign that he’s reaching the end of what he has to say about Doctor Who. This can hardly be called a surprise. He’s already done a season more than Davies, and somewhere in the midst of The Zygon Inversion he surpassed Robert Holmes for total minutes of Doctor Who written over the course of his career. Better to go out with glory than to wait around for another Series Seven to happen.

In this regard, it’s worth noting the content of Heaven Sent: a middle aged Scottish man is forced to do the same thing over and over again in an endless and nightmarish loop. This is certainly not the only thing going on in the script, but it’s clearly the case that the story can be read as a metaphor for television production and the sense of writing the same thing over and over again. On a very basic level, though both this and Blink are reveling in formal complexity and response to constraints, Blink is full of possibility and eagerness to try things. Heaven Sent is exhausted, its eye continually on the coming end, both diegetically and not. It feels like Moffat’s version of the Robert Holmes “fuck you for commissioning this” script (e.g. The Space Pirates, The Power of Kroll, or The Two Doctors), except of course that he commissioned it himself, and so can’t really throw his toys out of the pram in the same way. All the same, there is a similar angry cynicism at the basic nature of the request. “Oh, you want another big story that shows how good a writer I am? Fine. Let me tell you the story of my resignation.”

This is, of course, why it’s so good. Moffat has always been at his best when his work is motivated by a streak of anger. And more to the point, it’s generally when he’s trying to please everybody that his worst instincts are likely to strike. That’s not to say that every crowd-pleaser is a disaster; far from it. But the worst thing Moffat could have done for his crowning set piece would have been to try to please everybody. Instead he did a prickly, difficult episode that demanded attention and was in many ways even more dismissive of casual viewers than his season opener. Its AI figure, an 80%, is lower than anything else in the Capaldi era save for Sleep No More; the only other times the new series has been at 80 or below are Love and Monsters and the first three episodes of the Eccleston era. This after shedding 15% of the audience at the start of the season. To some extent it’s a wonder Moffat was brought back after an indulgence like this.

We’ll get to that part of things in good time, but for now let’s be clear that however we want to describe this—hubris, madness, or ambition—it is amazing and we are lucky to have it. There are at best a handful of moments in the series’ history where it has been this thoroughly bent out of shape and reconfigured according to a single person’s visions and preferences. The easiest analogy is probably the late Pertwee era’s steady drift towards, if not Buddhist parable, at least Barry Letts’s best understanding thereof. Past that, the closest thing is probably the early Davies era, where the show was overrun by his sheer determination to break all the rules about what Doctor Who could be.

Indeed, the Davies parallel is instructive, because there’s a similar story towards the end of his run: Midnight, which is similarly claustrophobic, companionless, and experimental. But Davies dashed Midnight out in in a feverish weekend of desperation, patching around a failed script to write a story more than he’d intended that season; it’s essentially an accident. Heaven Sent is planned genius, which is part and parcel of its vague cynicism. The comparison is on the whole odd; while I’m largely inclined to view Heaven Sent as the better episode, it’s oddly diminished by being put side by side with Midnight. Davies’ story, after all, is a work of smoldering anger—a contemptuous denunciation of the idea of human goodness. Moffat’s story, on the other hand…

I mean, nominally it’s about grief. That’s certainly the idea upon which its most explicit attempts at pathos are hung. But I watched this a couple of days after I had to put down my dog that I’ve had since before I got my PhD, and while I loved it, it had fuck all to say to the experience. The bit about grief and boredom resonates a bit, though more with my memories of staggering around Connecticut for two weeks after the weekend from hell in which my first marriage collapsed and my father had a massive stroke. It reads slightly better as recovery from mental illness with all the laborious futility implied, but as can often be the case with Moffat, ultimately it’s more a good line than a vivid depiction of human experience.

So in the absence of a strong sense of being about anything we are left with an episode that is essentially a demonstration of technical skill. Thankfully all of the people called upon are long on it. Moffat, as we’ve noted, crafts a script that’s as good as it’s clearly bragging that it is. Its technical problems are solved well and its reveal is a good one well-executed (although it’s worth noting that it works by being a straightforward opposite of Moffat’s usual “timey-wimey” solutions, making it at once a marker of cleverness and a sign of the well running dry). But it’s a script that asks for massive amounts from the people working on it, especially Rachel Talalay and Peter Capaldi.

Let’s start with Capaldi. Simply put, this isn’t something that would have been worthwhile without an actor of Peter Capaldi’s craft and discernment. Maybe you could have done this story with Matt Smith, but fundamentally his gregarious relationship with the camera is wrong for it. Fifty-five minutes with a character as loud as Smith’s Doctor is vaguely uncomfortable. Capaldi’s Doctor, who if anything can tend towards understatement, is suitable for this in a way nobody since Peter Davison really has been. And similarly, this just isn’t something you could throw at an actor during their first season in the part; it depends on a level of maturation. It serves the same role for him that it does for Moffat: it stakes a high point that manifestly will not be surpassed, the existence of which gestures at the inevitable finish line.

We have spoken previously about Capaldi’s generosity as a collaborator; the way in which he elevated Jenna Coleman’s performance by leaving her space in which to have it. And in an odd way this is his most generous performance yet, as he resolutely underplays every step of his own star vehicle, allowing Moffat’s script to rely on him instead of using it as a platform for soaring moments. God willing nobody is ever going to make Sylvester McCoy or Colin Baker improvise a speech from this at a convention. For all that this is an egotistical episode in every imaginable sense, the two male egos in the room are both admirably inclined to play it quietly.

Which leaves the third part of this episode’s triad, Rachel Talalay. Talalay, of course, is an eternally generous chameleon who gives each story what it needs without visible ego. But with Moffat and Capaldi getting out of each other’s ways and literally nobody else to call on she steps in and provides a foundation for it all. Her choice of expressionism is perfect for the material, honoring its ostentatiously gothic quality and vamping around enough to carry everything while still remaining fundamentally understated. It’s an exquisite choice that matches Moffat and Capaldi both in showing off and in getting out of everybody else’s way.

With the three major figures in this episode each hitting their marks with aplomb, the supporting players are left mostly to fall in line, which they do. The late and ever brilliant Michael Pickwoad could surely do a gothic castle in his sleep, but makes this one the most Gothic and Castley imaginable. Jenna Coleman makes every one of her thirty-five seconds in this story count. Even Murray Gold mostly keeps it in his pants, orchestrating the final act’s more or less constant crescendo without actually overwhelming it.

So we are left with an episode that is as much of a closed energy loop as the castle within it. Its sole idea is “what if everyone was just really fucking brilliant for fifty-five minutes or so?” And then everyone is. Being capable of doing that is worth celebrating. It is an act that justifies itself and all of the at times strained pacing of the episodes on either side of it that is required to make it work. It’s an act of sublime egotism on the part of a bunch of people who are every bit as good as they think they are. It’s astonishing, triumphant, an absolute gift, and yet in its wake there is an eerie and final certainty: nothing like this is ever worth trying again. No one involved will ever top it. Everything after this is just a victory lap. As of now, the Moffat and Capaldi eras are functionally over.

September 10, 2018 @ 10:16 am

I was nervous about this essay because “Heaven Sent” is probably my favourite episode of “Doctor Who”. Or at the very least the one that affected me the most emotionally. I was afraid you were going to tear it down. But you did this story justice and gave me a whole new perspective. Thank you, this essay is just brilliant.

I think one of the things that make this episode unique is the focus on the Doctor’s pain. We’ve never really seen him like this: scared, alone and grieving. Even when he lost the Ponds, we skipped most of the time he spent sulking in the TARDIS. But here we see it in terrifying detail. And it’s not just emotional pain either. I don’t think we’ve ever seen the Doctor so physically hurt, crawling with burned hands for a day and a half, bleeding the whole time just to inflict more pain upon himself and then die. Billions of times. This episode still haunts me sometimes.

This story is also where Twelve’s self-destructive period really begins. After “Heaven Sent” he becomes increasingly willing to hurt/sacrifice himself to help others – and after his final goodbye to River he becomes downright suicidal. In a way this story would never have worked with any other Doctor/companion pairing. For all his survivor’s guilt and all his “I’m so sorry” moments, I don’t think Ten would have agreed to inflict that much pain upon himself. Even for Rose.

“So in the absence of a strong sense of being about anything we are left with an episode that is essentially a demonstration of technical skill.”

Interesting. I agree that this episode isn’t really about grief but for me it is very much about something: depression. Or any kind of struggle with serious mental health issues. The loneliness of it, the horrible feeling of being trapped and helpless. Constantly running away from the monster you can’t escape and feeding it your soul so that it will give you a brief respite. Eating, working and sleeping with the monster always just a few paces behind you. Punching the impenetrable wall even though it hurts so much because if you keep doing it then maybe one day you’ll break through. That moment when the Doctor figures out the “BIRD” message, realizes how much more pain he will have to endure to maybe someday escape this hell and then just lies down because dying is easier? I have been there. Many times.

I don’t think this was ever the intended reading but this is how I see it.

September 10, 2018 @ 10:22 am

I would like to completely ‘second’ the depression reading (which I also see in “Listen”, personally) – and extend a virtual hug to you, if you would like one.

🙂

September 10, 2018 @ 10:30 am

Thanks. It’s all distant past for me now but damn, this episode hit the nail on the head.

September 10, 2018 @ 10:23 am

Oh yeah, there’s definitely what feels like a depression parable in there. Getting up every day to do the same fucking thing, not knowing how long you’re going to be doing it, working towards some vague light at the end of a tunnel.

September 10, 2018 @ 10:20 am

I think my favourite bit about this episode is that the Doctor’s worst nightmare is being trapped inside a Moffat puzzle-box plot. Which, hey, felt like my Doctor Who nightmare from 2010-2013.

Also I felt pleased as punch when I worked out the plot from the opening shots, because I hate plots and it really just let me enjoy everyone being very good.

September 10, 2018 @ 10:27 am

Why do you hate plots?

September 10, 2018 @ 10:25 am

I too adore this story – but it’s a shame that some who do seem to adore it as a standalone. It’s brilliant BECAUSE the next part of the story is “Hell Bent”, not despite that fact. It’s brilliant because it’s Part Two of a brilliant triptych, an Alchemical Great Work. Besides, as Steven Moffat said, the most important scene from this episode is actually in the next episode (Clara finding out how long the Doctor was in the confession dial).

September 10, 2018 @ 10:36 am

Yeah. There are so many people out there claiming that “Hell Bent” apparently “ruined the masterpiece”. If they don’t like “Hell Bent”, that’s fine. But claiming that it “ruined” the previous episode sounds suspiciously like saying that what they enjoyed most about the whole finale was Clara being dead.

September 10, 2018 @ 10:39 am

Nail. Head.

September 10, 2018 @ 10:38 pm

A lot of the beauty that people find in Heaven Sent is the slow cathartic process of him breaking down the wall being the representation of his grief at Clara’s loss. Removing her loss from the Doctor’s life and giving the character a fanfiction ending was tasteless, crude and insulting. Hell Bent was a huge misstep.

September 11, 2018 @ 5:51 am

How did Hell Bent ‘Remov[e] her loss from the Doctor’s life’?

Also, on a different point, do you use the word ‘fanfiction’ as an insult?

September 11, 2018 @ 7:32 am

Yeah, I imagine the term meant is more along the lines of “wish fulfilment”, but that isn’t the same thing, and this usage of fan fiction as a derogatory term is always a bit of a red flag for me. The boundaries between what passes as professional fiction and what passes as fan fiction are ridiculously hard to determine, and one could sum up huge swathes of literature as fan fiction if one were so inclined. Dante? Just wrote Virgil fanfic. Shakespeare? Plutarch fanfic. Dryden? Shakespeare fanfic. Thomas Mann? Goethe fanfic. All modern Doctor Who is essentially fan fiction in this sense.

September 11, 2018 @ 12:47 pm

A character close to the Doctor dies, through their own recklessness and deep-seated need to be on par with the Doctor, a need to be an equal, a need to burn as bright as the Sun. Clara as an egotistical Icarus, if you will. This character dies, at the hands of a throwaway secondary character, during what would otherwise be an obvious filler episode. All because they tried to be the Doctor. Because they admired him so much. Because they, in their own subtle way, idolised him. This tears the Doctor apart, and after being forced through psychological torture he realises that, like all the horror in his life, his own people are to blame. Does he return to Gallifrey and atone for his own perceived sins in some close-quarters character study that forces Capaldi’s Doctor through a heap of development and reintroduces Gallifrey not with a bang, but with the muffled firing of a hidden gun? No.

The character is brought back to life and given a TARDIS and the Doctor has a Mexican standoff with Rassilon and Moffat references the barn from Day of the Doctor and there are lots of little jokes and the old TARDIS comes back and it’s just lazy. It’s lazy and wishy-washy and disappointing. It’s not subversive. It’s not clever. It’s devoid of heart, devoid of wit, devoid of anything except for the faint call of Steven Moffat murmuring the word “clever” over and over again as he rocks himself to sleep.

Sometimes bad things happen, and Doctor Who keeps refusing to acknowledge this. It’s a huge blind spot for the Moffat era.

But, yes — wish fulfilment would have been much more apt. Fanfiction was a poor choice of term.

September 11, 2018 @ 1:24 pm

On the contrary, it’s the most heartfelt Doctor Who has ever been, for me. It makes me cry every time. In its juxtaposition of opposing emotional states – anguish, doing all the wrong things for the noblest and most caring of reasons, triumph, loss, tragedy, emancipation from narrative tyranny – and in the astounding plethora of unspoken moments where a gesture, a look, says far more than redundant, trite “I’m having a sad emotion” type dialogue, it’s as subtle as Doctor Who gets. It’s about memory, about how we tell stories, about taking the tropes of one type of story and applying a huge middle finger to them so we can get a far superior one. It’s got plenty of character development for Capaldi’s Doctor (don’t mistake character development you don’t like for none at all). It’s got buckets of heart, and some of the series’ most exquisite direction, and the single most feminist 7 words of Doctor Who yet written:

“I wanted to keep you safe.”

“Why?”

That beat, right there, is like a guillotine through every iota of received wisdom about DW. It’s spine-tinglingly perfect.

Lazy? That’s the worst media criticism there is. Not only is it used far too often to simply mean “I don’t like it” (perfectly valid; why does no one ever say that instead?), it’s a vacuous catch all term that ignores how much blood, sweat and tears goes into writing these things. No one deserves to call a script lazy unless they were round the writer’s house while it was in progress and frequently saw them giving up after twenty minutes, sighing “that’ll do”, and going down the pub instead.

September 11, 2018 @ 1:28 pm

Sorry, that should be “I’m trying to keep you safe” (just double checked the transcript).

One last point on the “avoiding bad consequences” thing – that’s not what Doctor Who or other shows for children are for. Fairy tales are real, because they tell children both that there are dragons in the world that want to eat them, and also that sometimes those dragons can be beaten. That’s not a cheap lie. It’s the best kind of social good you can do with children’s fiction.

September 11, 2018 @ 3:10 pm

Yes, it does look very nice, on a positive note, BUT —

“Buckets of heart” – it doesn’t. It’s nicks every single emotional beat from late-RTD Who, which, as eras to steal from go, isn’t very high up there.

“Single most feminist 7 words” – because that’s indicative of quality? Look, I understand where you’re coming from, but pushing against the idea of human beings as inferior to the Doctor and trying to subvert Terrance Dicks is not ‘bashing the fash’.

‘Loss’ – Hmm…

‘Most heartfelt Doctor Who has ever been’ – I just can’t agree with you there, I’m sorry. It’s a very unimpressive story, from my point of view.

Maybe different things touch different people in different ways.

September 11, 2018 @ 11:34 pm

Thanks for your long answers. I get where you are coming from. But…

How did Hell Bent ‘Remov[e] her loss from the Doctor’s life’?

At the end of Hell Bent Clara has been lost from the Doctor’s life. The ‘loss of Clara’ has been removed from our lives, not the Doctor’s.

September 12, 2018 @ 12:53 am

I suppose you’re correct there, though it’s mainly an issue of semantics. Clara is ‘lost’, yes, but she’s still, to an extent, alive and around and accessible as a person in-Universe.

Clara is not lost to the viewers, that’s true. But where is the line between the Doctor and the viewers actually drawn?

September 12, 2018 @ 8:51 am

Yeah, indeed, like most things it boils down to “different horses for different folks”, as the saying doesn’t go (I love a mixed metaphor).

I wouldn’t say the emotional beats are nicked from RTD-Who if, for example, the key one is an explicit repudiation of that view (the anti-Donna-mindwipe). Drawing from a similar well, perhaps, but that’s not quite the same as outright plagiarism.

“because that’s indicative of quality?” – Yes.

“Hmm” – I agree with Sleepyscholar’s point below, it’s the Doctor losing Clara (and her memories) that means so much to viewers (AIUI). This is one reason I really dislike him getting those memories back in Twice Upon a Time.

But as you suggest, strokes for courses 😉

September 13, 2018 @ 3:00 am

I didn’t think the Doctor got his memories back, more that he logically figured out that there had been a companion that he’d done all this stuff with.

Just as I logically know my parents fed me in the first two years of my life, even though I have no memories of this.

Having him “remember” in this way – by deducing what happened – helps avoid having plot threads where something that happened comes up, but the Doctor doesn’t remember. No loose ends.

September 13, 2018 @ 7:20 am

Well, in TUAT he explicitly says “All my memories are back”.

September 12, 2018 @ 8:51 am

I thought Doctor Who was generally against keeping companions safe in the first place. That’s why it has them travelling in the TARDIS and getting into all kinds of perils instead of staying home and eating chips.

September 12, 2018 @ 8:54 am

Well, the implicit dynamic of the patriarchal male lead and his plucky female sidekick is that the Doctor saves the assistant when the assistant needs saving. Sure, it’s travelling with the Doctor that gets her into danger, but it’s traditionally the Doctor who gets her out of said danger.

September 12, 2018 @ 10:04 am

I think that’s just far too weak a rule to start calling “received wisdom”. You have companions saving the Doctor sometimes, not as frequently for sure, but it’s hardly rare, you have plenty of examples of companions dealing quite well with the peril themselves, and you have male companions too, who aren’t in general any better at all this than the female ones, because the main dynamic here is “hypercompetent character and ordinary characters” not “men and women”, which makes it really about the failure to imagine a female source of mystery and science in 1963.

The Doctor rescuing the (female) companion all the time isn’t any piece of “received wisdom”, let alone every iota of it. It’s a generally acknowledged bad habit. If anyone points out how much Victoria needs to be rescued, for instance, they’re almost certainly being critical.

And once a writer has written a situation in which one character is imperilled by something they can’t get out of, but another character can get them out of it, then doing so is unambiguously a good thing for the character, and asking them ‘why’ doesn’t make any sense. The ‘why’ would need to be directed at the author. The things which the Doctor is doing wrong in that story are being incredibly selfish about his decisions of when to break time, and ignoring Clara’s wishes in the process, those are the things Clara can coherently ask him ‘why’ about. It’s Moffat who has decided to write the story that way, instead of, say, just writing a story in which the Doctor gets into trouble and Clara saves him.

September 12, 2018 @ 10:12 am

Received wisdom here = what people / the general public typically perceive about Doctor Who. I didn’t say it was accurate received wisdom (in fact received wisdom often isn’t remotely accurate). And it is still plenty common an assumption that that is fundamentally the role of the male lead in relation to the female sidekick.

“And once a writer has written a situation in which one character is imperilled by something they can’t get out of, but another character can get them out of it, then doing so is unambiguously a good thing for the character” – nonsense, otherwise there would be no such thing as trolley problems. Of course it isn’t unambiguously a good thing, if for instance it involved bringing the entire universe to an end or killing somebody or any other negative consequences.

September 12, 2018 @ 10:15 am

Besides, Moffat has written stories about Clara saving the Doctor plenty of times. There was a whole finale about it, she was born to save him, and all the rest of it.

This is a different story.

September 11, 2018 @ 1:32 pm

So instead of an empowerment of a female character who ascends to being the Doctor’s equal you’d rather have a Whithouseian focus on the manpain the Doctor feels because what he does is oh-s-difficult?

September 11, 2018 @ 3:14 pm

I’m not going to rise to the bait over whatever ‘manpain’ is, but I’d just like to say that when you find yourself at the point where speaking about anything felt/done by a male needs the word ‘man’ in front of it, and you’ve successfully almost completely othered half of the world’s population from yourself, then there’s something a little bit off there, and you need to take a look at yourself.

September 11, 2018 @ 8:32 pm

“Manpain” has been a common term of art in online media criticism for something like two decades now. It refers to storytelling choices that prioritize exploring the emotional suffering of male characters, not to real suffering experienced by non-fictional men. So A) I very much doubt that mx_mond used that term with the intention of baiting you, but B) if it had been bait, posting a paragraph-long comment complaining about it would definitely qualify as rising to it.

September 12, 2018 @ 12:50 am

Rising to the bait would have been some sort of vitriolic tirade in response. I simply tried to (obliquely, perhaps) offer advice to the commenter re: their personal politics.

September 11, 2018 @ 8:49 pm

🙄🙄🙄

September 12, 2018 @ 8:26 am

“Sometimes bad things happen, and Doctor Who keeps refusing to acknowledge this. It’s a huge blind spot for the Moffat era.”

God forbid we had one feel-good slightly unrealistic TV show out there where bad things that happen to us can always be at least somewhat softened if not outright reversed. It’s not like we have literally hundreds of other TV shows where people just suffer and die senselessly like in the real world.

Also, so (apart from your opinion on the quality of the story itself, which is perfectly valid) what you’re saying is that what you enjoyed the most about Series 9 finale was Clara being dead?

September 12, 2018 @ 4:24 pm

Let’s set aside the assertion that once one removes the whole core of an episode, what remains is “filler,” as if that weren’t what happens by definition. (This point is further down the thread but nesting here rapidly becomes unreadable on mobile.)

Your claim is that by denying “sometimes, bad things happen,” an episode which we’ll be talking about next Monday completely spoils this one (which I note you don’t seem to engage with much in your comments). You suggest this is a characteristic of the “Moffat era.”

Over the entire history of the program, companions have been menaced repeatedly, put into terrible danger. Of them all, only three die in stories of the classic era; two in the same mega-story, one in the 5th Doctor’s era. Peri’s seeming death gets retconned in a much more callous and poorly executed way than Clara’s. And in fact, the show is highly critical of how far the Doctor goes to bring Clara back, not too long after a failed attempt to bring Danny Pink back.

Seems like Moffat is being far better about the whole “sometimes bad things happen” thing than any other era of the program. Heck, Peri was restored at the last minute under JNT, whose programs didn’t exactly shy away from brutality and death.

And it sounds like you’re more upset at Moffat because he gave you what you always wanted from the series and then took it back than you are at all the showrunners who didn’t ever contemplate giving you what you wanted.

September 10, 2018 @ 10:41 am

Aye, I’ve never really understood the tendency to separate Heaven Sent so decisively from Hell Bent (which is probably my major disagreement with this essay – I’d say the Moffat era ends with Hell Bent, i.e. at the completion of the series 9 finale). IMO, this is clearly a two-part finale, with Face The Raven a Utopia-style lead-in story.

I was dealing with some pretty intense loneliness and issues around work when I first watched this story; I thus found it relatable, but coming back to it more recently I was struck by how little it had to say in retrospect; a parallel rather than a metaphor, perhaps.

I would point out, though, that as well as grief and mental illness, toxic masculinity is another vector through which to read the episode. I’ve said elsewhere that this episode can be seen as typifying the impulse some men have to internalise their suffering; the Doctor deals with losing Clara in the most painful and self-isolating way imaginable, to the point where when he finally meets Clara again he’s almost unable to talk to her. And Hell Bent stresses that the Doctor could have confessed (i.e. reached out to others for help) any time he wanted, so his refusal becomes somewhat pathological.

Anyway, excellent essay as always; bring on Hell Bent!

September 10, 2018 @ 12:20 pm

Hmmm. I think that depends on ascribing a metaphorical pattern to the story that is too uncomfortably at odds with what happens in it on the literal level. There is a world of difference between asking for help and complying with an interrogation.

The person who makes the point that “He could have left any time he wanted” is the General, who, however uneasily, is complicit in torturing the Doctor(s) for 4.5 billion years. And that “Why make it hard on yourself?” sentiment is a standard part of the logic of torture, and one that more generally emanates from authority in the direction of anyone resisting pressure and coercion, at whistleblowers and dissidents and nonconformists of all kinds. Sometimes cynically, sometimes truly more in sorrow than in anger, but the effect is much the same. Why cause yourself so much suffering, why throw away your future over such a little thing? Just tell us what we want to know, just do what you’re told, just do what everyone else does, just play the game, just let it go and press the button marked Forget. Everything will be so much easier.

That’s never been the Doctor’s way, it’s not a good position to align oneself with, and I certainly don’t think you mean to. But it seems the inevitable concomitant of saying that the Doctor was acting foolishly by not cooperating in order to spare himself pain. (Whether or not his goal of “saving” Clara is a good one in the first place is, I think, a separate question.)

And even apart from all that, I’m not so sure about the putative message itself. Seeking help is good, but even if good help is available, as it often is not, there is a limit to what it can do in dealing with grief or depression or anything of that sort. “Confessing” does not fix things just like that. You still have to keep doing the days for a long time, sometimes indefinitely, as the Doctor does. “Just get help” can be an infuriatingly condescending message to people still struggling with problems they have been seeking help with for a long time. People with such problems can also be susceptible to thinking that they are just being silly and self-indulgent, that their troubles are self-inflicted, and that’s not good either. So it would seem to me a rather glib and potentially unhealthy line to take on the story.

September 10, 2018 @ 12:36 pm

That should really be “line for the story to take” at the end there – I don’t mean to have a go at you for reading it that way, just to look at what such a message in this form would amount to.

September 10, 2018 @ 12:47 pm

Everything you say is true… and yet there are many, many men (not just men, but mostly) out there who never ask for help, even when in dire need of it. I personally know a few myself. They never reach the limit of what a “confession” can fix because they never “confess”. Sure, “just get help” is condescending but “you don’t have to deal with the pain alone and in silence, here’s how” can literally save lives. I’d say that’s a message worth sending.

But I’m discussing real life situations here. As for the episode, as much as I like William Shaw’s reading, I don’t think it holds up because, as Aylwin points out, the Doctor is being interrogated by the enemy and is unlikely to receive any help from them. And what’s more, “Hell Bent” later shows that the Doctor’s self-sacrifice worked – it ultimately saved Clara. His suffering is clearly presented as an act of love and that’s how Clara herself perceives it. This makes it hard to map “Heaven Sent” onto the real life issue of people dealing with their pain in a self-destructive way.

September 10, 2018 @ 12:59 pm

Fair enough; I certainly didn’t mean to indulge condescending stereotypes, or endorse strict compliance with torturers, but I’ll cop to not paying that enough consideration in my reading.

I would push back on slightly saying the Doctor’s sacrifice straightforwardly works – Hell Bent repeatedly stresses that the Doctor is going too far to save Clara, that Clara didn’t want or need him to do this, and I think the dynamic between them in the episode is explicitly shown to be unhealthy (more so than usual, anyway).

Other than that, you’ve got me bang to rights. Apologies for failing to think through my reading properly.

September 10, 2018 @ 1:30 pm

You’re right about “Hell Bent” casting doubt on whether the Doctor did the right thing. But at the very least the sacrifice brings Clara back to life. Which doesn’t map onto any real life situation but can still be read as an endorsement of suffering in silence.

I just realized Series 9 finale, with its “death can be defeated” plot, would probably appeal to Eliezer Yudkowski and his Less Wrong fans. The Doctor using his pain to fuel his determination and find a way to resurrect Clara is actually very similar to the plot of Yudkowski’s “Harry Potter and the Methods of Rationality” where the same thing happens with Harry and Hermione. Which is… not a comforting thought.

September 11, 2018 @ 8:40 am

Which is… not a comforting thought.

I’m confused – is it not comforting because of the connection to a shitty fanfic and a shitty fandom, or because of the “death can be defeated” plot?

September 11, 2018 @ 9:28 am

The connection, mostly. (Although I enjoyed the fanfic very much. Deciding to ignore all the rationality lessons definitely improves the experience). As for the “death can be defeated” plots, for me they’re enjoyable and feel-good but they always leave the bitter aftertaste of “shame we can’t really do that” in my mouth. Although others may feel differently, of course.

September 10, 2018 @ 2:07 pm

I would push back on slightly saying the Doctor’s sacrifice straightforwardly works – Hell Bent repeatedly stresses that the Doctor is going too far to save Clara, that Clara didn’t want or need him to do this, and I think the dynamic between them in the episode is explicitly shown to be unhealthy (more so than usual, anyway).

This also ties into one of those recurrent Moffat patterns, linking to the Doctor “saving” River in the Library and her not-entirely-approving view of that action and its underlying psychology in Name (“he doesn’t like endings” and all that, and the related matter of her insisting he not rewrite her earlier life, “not one line”), and to Clara’s similarly extreme drive to “save” Danny after his death in Dark Water. In the matter of overbearing intervention in the course of others’ lives and deaths and their choices about them, it also ties in with the mindwipe denouement and its own link back to Donna.

There’s a thought, actually, in the context of Clara mirroring the Doctor – arguably, the similarity of his behaviour here to what she did last season means that the last leg of their story involves him mirroring her, which can itself be seen as an affirmation that she has completed the process of acquiring Doctor-like status as a character, such that she can be the pattern that he reflects rather than the other way round. (Though the precedent of River in the Library does muddy that one up a bit.)

September 10, 2018 @ 2:42 pm

Well, River was never really a companion – her Doctor-like status was pretty evident from the very beginning. And he was mirroring her as early as “Silence in the Library”, repeating her “Spoilers!” catchphrase. Clara is still the first character to go from a companion to a Doctor on her own right.

Very nice analysis of the mirroring (and the link to Donna).

September 11, 2018 @ 10:18 am

Sorry, I wasn’t clear – when I said a precedent, I meant in terms of the Doctor having already done something comparable before Dark Water, so diminishing the sense that he is now echoing Clara’s actions there. Though of course, the River case is a bit different, not having the same notion of this being alarmingly extreme, going-against-nature behaviour (and of course at the time it is presented in straightforwardly positive terms, with Moffat apparently having had second thoughts about it later).

But of course you’re right about the differences between River and Clara (and there is also the fact that Clara is human).

September 10, 2018 @ 1:27 pm

Yes, I agree with that – it’s just that easy, “quick fix” aspect of it that makes me feel that this would be a poor way of sending that message (along with the poor fit with the story context).

September 10, 2018 @ 1:35 pm

You’re absolutely right. Also, that should have said ‘push back slightly on’.

September 10, 2018 @ 10:47 am

I often disagree with your opinion on episodes, but your comments are never less than interesting and challenging. I’m very happy to see we agree on this.

It’s interesting to see that, going back and rewatching and reappraising this season, you’ve had a lot new to say about other episodes, but this one boils down to “Yup – still great”.

For me, the only downside to it (one it doesn’t share with “Blink”) is the impossibility of using it as a gateway for Who newbies (Whobies? NO!). You can’t show this to someone without context and expect them to get it or care. But it’s a faint criticism – it has earned its place. I love it. Thanks for this and all your other stuff…

September 10, 2018 @ 11:32 am

The only problem I have with this two(?) parter, which I love and consider top ten, is that “Hell Bent and Heaven Sent” was going to be the name of a comic I was going to write about an angel and a demon teaming up to solve crimes, and now it’s going to seem even more derivative than I already planned for it to be.

September 10, 2018 @ 1:24 pm

Call it “Hell Sent/Heaven Bent” instead :p

September 10, 2018 @ 2:43 pm

Congrats on the caption! (so to speak)

September 10, 2018 @ 2:53 pm

“In this regard, it’s worth noting the content of Heaven Sent: a middle aged Scottish man is forced to do the same thing over and over again in an endless and nightmarish loop.”

Heh.

September 10, 2018 @ 3:23 pm

Addendum: it’d be interesting to know what Jack thinks of this story too. I suspect it’s not necessarily the best one to win over Moffat-sceptics, but…

Re: comparing this to Midnight, which I’ve been pondering – I think Dr Sandifer is right in that the earlier story is clearly about one particular thing, it has a basic thesis (or “Argument” as Milton might have put it). Which Heaven Sent doesn’t, really. But as is already evident even from the comments here, but more broadly from the various things other critics have said about it, this is a story immensely open to different interpretations, whether it’s about grief or despair or existence’s daily grind or the factory mindset of the television industry or toxic masculinity or the basic repetitive nature of Doctor Who plots. Everyone will scan or gloss the palimpsest in a different manner, if you’ll forgive my medievalist phrasing.

Both are entirely valid, and beautiful, approaches to art.

September 10, 2018 @ 9:17 pm

Actually, the castle mostly exists. It’s Cardiff Castle. With a bit of Caerphilly Castle.

September 10, 2018 @ 9:21 pm

I love this episode, but I think Moffat has done better in his career. Listen, Blink, and World Enough and Time are all better, in my opinion. I would maybe also include the Library and the Empty Child two-parters.

Also, I think Murray Gold deserved more praise for this episode. The score was absolutely beautiful.

September 11, 2018 @ 7:40 am

It was, wasn’t it? I listen to it from time to time and I’m always amazed. There’s even, I think, a brief nod to the Classic Who music in “A Fly on a Painting”… Not to mention “The Shepherd’s Boy” which proved so memorable that they reused it for Capaldi’s regeneration. Quite right, too.

September 10, 2018 @ 11:05 pm

So Elozaneth I know that Tardis Eruditorum is not a “review” blog, but I’m still really surprised at how different your assessment of “Heaven Sent” is in this analysis than in your normal Eruditorum Press review when the episode aired. If I recall correctly you stated after airing that this was just above average Doctor Who but not the outright classic everyone thought. Now you seem to have come around to the same conclusion as everyone else – that “Heaven Sent” is one of greatest episodes DW has ever done. What changed from then to now that altered your perception?

September 13, 2018 @ 8:13 am

“Maybe you could have done this story with Matt Smith, but fundamentally his gregarious relationship with the camera is wrong for it. Fifty-five minutes with a character as loud as Smith’s Doctor is vaguely uncomfortable.”

I propose we play a game of “How would this story play out with other Doctors?”. Because all I could think about when I asked myself this question was that Ten would have died the first time the the Veil cornered him by the locked doors, screaming at it angrily that he’s the Oncoming Storm from the planet Gallifrey in the constellation of Kasterborous.

September 13, 2018 @ 3:52 pm

One would have needed Ian or Steven to smash the wall for him.

September 21, 2018 @ 3:09 pm

A version of this with Seven could work

September 25, 2018 @ 6:06 pm

The War Doctor would have not even wanted to survive at this point.

September 15, 2018 @ 8:46 am

I feel there’s almost a generational theme in this story. Each Doctor commits their minutes-long lifespan to the set task of breaking through the crystal barrier before having to leave the job to the next Doctor when the freaky space Dementor gets him. For billions and billions of years.

The classical Science Fiction model is built around this idea of the pan-generational utopia-building project. Of planting the tree that you’ll never get to sit under the shade of.

The Doctor usually gets to casually flit across time, admiring these projects from afar from his usual cosmic perspective, like in his Ark in Space speech or his Great and Bountiful Human Empire Speech. Now we finally get him put his money where his mouth is. Devote his infinite lives to his own Great Project.

September 18, 2018 @ 9:30 am

Forgive this late and peculiar comment, but I learned what diegesis is from this posting. One of those shocking moments where you discover there’s a word for a concept you subconsciously understood, dragging it suddenly into conscious understanding.

September 20, 2018 @ 8:10 pm

“Davies’ story [Midnight], after all, is a work of smoldering anger—a contemptuous denunciation of the idea of human goodness.”

Honestly, I never got that impression since, at the end, the day was saved by one character’s heroic self-sacrifice. I saw it more of a denunciation of Ten’s arrogance and hubris, which ultimately was what tipped the situation from “alarming and unsettling” to “nearly fatal.” When the Eruditorum covered this story the first time, there was a lively discussion about how other Doctors would have fared in Ten’s place, and the consensus, IIRC, was that he was perhaps the worst possible Doctor for that scenario. Given how Tennant’s remaining episodes played out, culminating first in The Timelord Victorious and then in Ten’s apparently serious consideration of just letting Bernard Cribbins die so he could live on, I think Midnight represented the beginning of RTD’s “regeneration arc.”

September 25, 2018 @ 6:02 pm

I watched the episode a year before my grandfather died. Through that time, me and my family were resigned that he wasn’t going to get better.

The days after my grandfather died were horrible, we had the funeral the very next day, which I know was really not the norm. I never knew why they couldn’t have waited a few more days.

The days afterward I tried to keep on living.

The days before I found my way back to the united states were dreay, repeative, with the end goal in mind, that things would be better in the country that I was born from.

With this in mind, I can watch the episode, but not without feeling, reliving some part of the last day I saw my grandfather alive, sending him to the hospital.

April 26, 2024 @ 7:50 pm

That offhand line about no one else being up to the task since Peter Davison is so tantalizing. Peter Davison Heaven Sent…