Who We Want To Be Next (Twice Upon a Time)

|

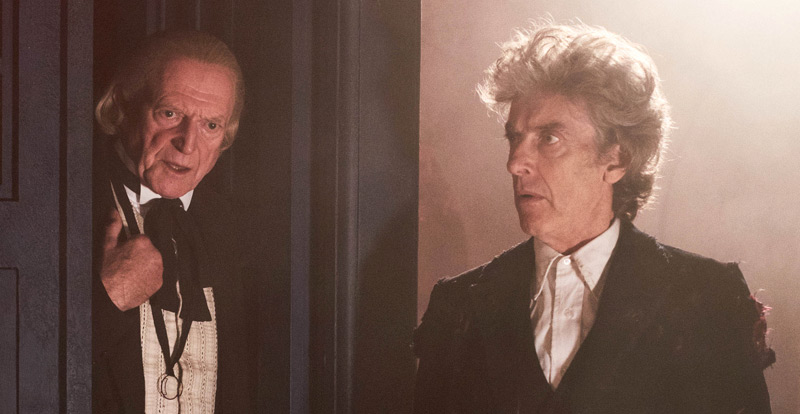

| In 2063 they should do a special in which they cast different actors as William Hartnell, Richard Hurndall, and David Bradley, then have them all appear together in an adventure called The Three First Doctors. |

It’s December 25th, 2017. Ed Sheeran is at number one with “Perfect.” The Pogues, Mariah Carey, Wham, and Eminem also chart, one of them with Ed Sheeran appearing on the track. We’ll call this an exercise for the reader. In news since Series Ten wrapped up, neo-Nazis held a rally in Charlottesville, Virginia that resulted in the death of a counterprotester, Heather Heyer, when a Nazi deliberately drove his car into a crowd. Following the rally, President Trump praised the “very fine people” on both sides of the “are black people human” issue. There’s a lot of other Trump bullshit, but honestly summarizing six months of it in a paragraph is a challenge, so let’s just leave that at “also more fascism” and call it a day. Martin Shkreli is found guilty of a variety of crimes including disrespecting the Wu-Tang Clan. Vince Cable becomes leader of the Liberal Democrats. Theresa May’s government promises that Parliament will get a vote on any Brexit deal. Fifty-eight people are killed at a concert in Las Vegas when a gunman opens fire from an overlooking hotel window. Disney announces its impending acquisition of 21st Century Fox, delighting Marvel fans who don’t give a shit about growing corporate control of the media landscape, which is to say Marvel fans. Also, I start transitioning, which isn’t exactly news, but given the autobiographical strand of this project seems worth mentioning.

On television, meanwhile, the Moffat era ends how a lot of people would expect: an undisciplined and messy story long on misplaced confidence and casual sexism. That the people who expected this were mostly wrong about the entire rest of the era is ironic, but does not change the underlying matter here. It’s not that Twice Upon a Time is bad; merely that it isn’t great. It’s not a triumphant final statement of any of the eras that it closes, instead coming off as sort of line one of those decent but clearly extraneous bonus tracks that get put at the end of album rereleases and end up vaguely diminishing the album’s close. It would have been a better ending for the Capaldi era had it closed with a slightly longer World Enough and Time/The Doctor Falls that found time for a regeneration speech. Not, again, because this is a bad story, but simply because that was an emphatic statement and this is a pleasant mess.

This is not a surprising, given that it’s the second extension of the Moffat/Capaldi era that we’ve had. After being persuaded to stay one more season after his “could be my last” Husbands of River Song, Moffat discovered that Chibnall did not wish to kick off his tenure with a Christmas episode, and so agreed to figure out his third way of departing the series in two years. It’s not exactly surprising that this effort is, comparatively, a bit muddled. This is a desperately inessential piece of Doctor Who. Moffat doesn’t quite go on autopilot, simply because he’s got too much of a sense of occasion to do that on his and Capaldi’s last story, but he leans hard on established tricks: causality jokes, a quick jaunt to visit Rusty, more Lethbridge-Stewarts, villains that aren’t, mythologizing the Doctor, and more.

Perhaps the biggest sign of exhausted desperation here, however, is David Bradley’s presence as the First Doctor, or something thereabouts. Bradley is making even less of an effort than Richard Hurndall did to get Hartnell’s mannerisms down, and Moffat is making even less of one to write him accurately. What we get is a sort of metonym for the basic idea of “the original Doctor” in a narrative sense that’s essentially untethered to the historical television show. Being done by a tired Moffat, it’s unsurprising that this involves a lot of humor along the lines of “the First Doctor as embarrassingly sexist uncle,” although there’s something to respect in the cheek of having his most egregious line be a quote from The Dalek Invasion of Earth. But dramatically speaking, it’s not quite clear what he’s doing here in the first place. There’s parallelism in them both refusing to regenerate, but his refusal is an anachronistic kludge with no real setup in the Hartnell or Capaldi eras, and he doesn’t actually play any role in Capaldi’s decision to regenerate after all, which makes his overall existence in this story feel like a vaguely superfluous gimmick.

This is not a larger existential problem for the Moffat era any more than Series Ten at large is. Indeed, it’s in one sense a more honest ending, in that Moffat didn’t leave at the height of his powers but rather just past the peak, in the early but manageable stages of terminal decline. Ultimately, Twice Upon a Time has a negligible effect on the aesthetic quality of the Moffat era. And yet it’s hard to pretend that endings don’t matter. It’s not as simple as saying that endings define everything that came before, but they carry disproportionate weight. And so we have to take seriously what Moffat chooses as his final statement, not because it selects the correct path among the many ambivalences and redemptive readings we’ve charted so far but because it at leas tells us a lot about what he thought he was doing all this time.

Is it out of line to point out, then, that Capaldi’s final speech is easily one of the worst things that Steven Moffat has ever written? It’s tempting to leave aside the gobsmacking twaddle that is “only children can truly hear your name,” a claim that finally discovers the point at which I get annoyed at the show sliding into fantasy logic by having the Doctor just actually become a fucking faerie, except that this doesn’t even capture the full absurdity of it because A) River Song is not a goddamn child and B) this is not actually sensible piece of advice to give your successor as it is not so much a moral position about how the Doctor should be as a piece of plot trivia, essentially akin to gasping out “Daleks run on static electricity” before expiring, except that might have been a better line.

But while we obviously did not in fact leave that aside, it’s not even the worst part of the speech. That would be the speech’s basic moral position, or rather, utter lack of one. Making Terrence Dicks’s famous “never cruel or cowardly” edict explicit text in The Day of the Doctor was a neat trick, especially as it bothers to keep the rather more important “he never gives in and he never gives up” bit from after it. Echoing it in Listen and Hell Bent was fine, since it was exactly that: an echo. Turning it into the whole of the Doctor’s ethos alongside such vapidities as “hate is always foolish and love is always wise” and the twice repeated “be kind,” on the other hand, starts to feel like an active attempt to remove any actual affirmative commitment on the part of the Doctor. Conspicuously absent are things like “stand up to bullies” or “overthrow tyrants” or “try not to shill for Space Amazon,” some of which, it turns out, are rather important.

In raising this objection I’m trying hard not to fall into the stereotype of my work in which I insist on every Doctor Who story flattering my politics at all times, because that’s not actually my point. My point is not that I want Peter Capaldi to recite the entire Communist Manifesto before exploding into glowing light and becoming a woman. OK, actually, that’s a lie and I 100% do want that, but I’m not upset that I didn’t get it. But I think there should be something—some sort of moral value somewhere that isn’t just “be kind,” a bromide that sounds depressingly like the oft-expressed viewpoint that the problem with Trump isn’t that he’s a recklessly corrupt would-be dictator running concentration camps but that he needs to be more civil.

And that’s really where things break down. It’s always been a problem with Moffat. His fondness for the reveal that the monster isn’t really one isn’t a problem in and of itself; it’s a good twist that speaks to the value of empathy and the fact that things are often more complex than they might first appear. And I generally take a dim view of those who criticize it on the grounds that they miss good old fashioned nasty monsters. But the aversion to villainy belongs to a politically utopian moment that, by 2017, had not so much passed as been aggressively murdered by literal fucking fascists. It turns out there actually are corners of the universe that have bred the most terrible things, and they must in fact be fought.

And that was never Moffat’s bag. He could be stirred to occasional righteous fury, but the truth is that His Last Vow is an aberration. Most of the time, even when he’s being thorny and difficult, he’s not actually being thorny or difficult at anything. That doesn’t diminish Dark Water/Death in Heaven or Hell Bent (although it might diminish The Beast Below a smidge), but it’s nevertheless a clear limitation on them—one of the ways in which Moffat says “this far, but no further.” And it shows up as well in the episode’s frankly bewildering assertion that the only reason that good prevails in the universe is that the Doctor has single-handedly fixed it all. It’s a horrifying mixture of Moffat’s tendency to over-mythologize the Doctor, great man theory, and the underlying vapidity of asserting that evil is rationally superior to good, or for that matter that good intrinsically prevails in the universe. It’s a vision of the Doctor that Boris Johnson could plausibly say that he sees himself in and when you do that you’ve definitely fucked up.

These tendencies weren’t always a problem. Or at least, they weren’t always a dealbreaker. Or hell, maybe that’s too generous; Jack certainly would say it was. But in 2017, they lead to a program that’s simply not fit for purpose. Twice Upon a Time does not provide a vision of Doctor Who that is worth continuing. Instead it reaches a dead end and then has the good grace to expire.

Where do we go from here? Well, there’s several answers to that. In one sense, we go away; I’m done writing TARDIS Eruditorum for at least another year, and that’s only if Chibnall and Whittaker both go at the end of Series 12. Which is another answer to where we go—an era that fails to address any of the problems I’m pointing out here anyway, and that therefore makes it difficult to come to any sort of clear conclusion about them. We could talk about what following the Moffat era should have looked like instead, but we’ve already answered that pretty well: something a little more materially engaged, more focused on big ideas, and with someone other than a middle-aged white guy writing it.

So instead let’s end with the obvious and traditional approach: the farewell to a major creative figure. After all, as we’ve noted before, Moffat has written more cumulative minutes of Doctor Who than literally anyone else. More than just that, he’s the writer who inspired this whole project. I started it back in 2011 off of the buzz and excitement that Series Five had left me with. And he’s brilliant at it. He’s written multiple contenders for greatest-ever Doctor Who story. More than that, he’s written stories that are contenders to multiple sects of fandom. The traditionalist Doctor Who Magazine crowd can and does go wild for The Empty Child/The Doctor Dances, Blink, and The Day of the Doctor, which are already three very different stories. Another type of fan adores the joyous frockery of The Pandorica Opens/The Big Bang or The Eleventh Hour, and no doubt found plenty of other stuff to love in the Smith era. And then there’s the stranger chunk of fandom that adores Hell Bent or Dark Water/Death in Heaven. It’s an impressive resume, and much more varied than you might expect from someone with such an instantly recognizable and definable style.

And yet after all of this, it’s strangely difficult to send him off with unalloyed valediction. Is it simply the defensiveness with which we’ve so often had to treat Moffat coming home to roost? It remains true that his handling of gender is something that it’s very difficult to begrudge someone disliking, even if many of the critiques of it are poorly articulated. Certainly it’s enough of a thing that, for all that I love and will defend it, I note as an asterisk before recommending the era to anyone. But we’ve litigated that issue extensively, and I’m certainly not going to back down on it at the last moment. There are solid feminist and, for that matter, trans readings of the Moffat era, and these readings meant the world to me.

But that’s the thing. They meant. Their moment passed. When all is said and done, perhaps the most extraordinary thing about Moffat’s time on Doctor Who is that he was able to give his vision a full airing. He reached the end of what there was to say about Doctor Who in the manner he was capable of saying it. This isn’t unprecedented; Barry Letts and Terrance Dicks did the same. So, in all likelihood, did Philip Hinchcliffe and Robert Holmes. And Russell T Davies, for that matter. But nobody’s approach feels quite as thoroughly exhausted as Moffat’s. It didn’t overstay its welcome, but more clearly than any other era that managed that, it came to the exact and precise edge of that. We have all the Moffat-style Doctor Who that we need. History is a part of that, but it’s not all of it. We also just actually and legitimately reached the end of the train of thought.

If influence and the passage of time work the way they’re supposed to, which is no safe bet in the dying days of the 2010s, Moffat’s style will be revisited, just as every other important style of Doctor Who has been. Some of these revisitations will be overly slavish recreations, and I suspect that this will go worse for Moffat traditionalists than it has for the fans of many eras simply because so much of his era works because of his precise talents and his capacity for pulling things off that weren’t necessarily good ideas and probably shouldn’t actually have worked. Others will go in new directions, finding room to build on these ideas that simply aren’t obvious yet. But the way that the Moffat era should be responded to is the way that any greatest of all time should be: by trying to surpass it. The only way that Moffat’s legacy could truly fail is if it is a high water mark: if nobody looks at this with the hungry itch to do it better. But if they do—if what the Moffat era brings is a generation of fans who take to creative labor high on possibilities and with the giddy, arrogant joy of coming at the king—then in spite of everything, and in the face of all the cavernous horrors the 21st century is contriving to bring, there might just yet be hope.

That’s a wrap once again for TARDIS Eruditorum. Please check back on Monday for the start of my next project, Boys in Their Dresses: A Psychodiscography of Tori Amos.

July 29, 2019 @ 5:26 pm

I wanted to congratulate you on another great round of Eruditorium-though it saddens me that this one seems to be more bittersweet because unlike last time, we don’t know if the future is in great hands.

One will be very curious to see what Moffat’s reputation will be in the coming years, but I’m much interested, like you, in what his legacy will be. I hope that it will be a show that challenges the conventions of what Doctor Who and Tv in general is capable of creating. Unfortunately, the bland dross of Series 11 makes me sad to say that legacy is currently unfulfilled.

But you know what they say: where there’s tears, there’s hope….

July 29, 2019 @ 5:33 pm

Excellent summary of the episode and its relation to the era, but I do think you underestimate “be kind”. Be kind, and you can’t run Amazon by abusing workers, manipulating authors, and crushing small businesses. Be kind, and you can’t be the Republican Party, stealing from the working class and the poor and everyone in the future. Be kind, and you can’t be Rupert Murdoch, building an empire on vicious lies.

“Be kind”, taken by everyone as a Kantian imperative, would result in a world with virtually none of our largest problems. It’s not “be more polite when stomping people”. And it’s not uniformly bad advice even in democratic conflict, where kindness can’t convert the enemy, but is often an excellent way to convert the muddled people who’ve casually sided with them.

“Be kind” is also not a definitive or fully satisfying summary of the Doctor’s ethos, of course. But still.

July 29, 2019 @ 5:46 pm

…bloody typical, I wrack my brains trying to make the same argument for hours, and by the time I post and the page refreshes, someone else has expressed it way better than I ever did. You have my aggravated thanks.

July 29, 2019 @ 7:08 pm

That is a good way to look at “be kind” if you aim it at those you believe are exploitative and doing injustices. On the other hand, I found “Be kind” to be a form of tone policing, appealing to be moderate in tone as well as in behaviour. There is no space for righteous anger in “be kind” and not even space for systemic change (even in the examples you gave) that would actually take away power from the privileged. At least that’s how it resonated with me. I also saw it as an exhortation to be civil, especially in light of the #NotMyDoctor stuff that was going even before a single episode had aired, which is fine.

But, given that, it is particularly jarring when it reads like a laundry list of instructions to the next Doctor in the same series where this Doctor punched a racist. And the optics are worse if you know that the next Doctor is a woman.

The speech was carried by Peter Capaldi’s acting and not by the content, which is unfortunate, as Moffat is more than capable of writing eloquent, powerful language.

Overall, I just felt sad that the episode did not live up to my expectations of being the last Moffat and the last Capaldi episode. I wanted it to be a truly memorable one and it ended up being just mediocre.

As an aside, I heard (I think from the last Moffat interview) that Moffat made changes on the last day and he gave the impression that Capaldi had asked from some changes (perhaps somethings did not flow right). I have always wondered what the changes were but I guess we will never know.

BUT unlike the episode, this was a fantastic end to Elizabeth’s Eruditorum. Excellent essay and thanks for sharing your wonderful insights all the way. I am sad it has finished. Thanks to you, I will always remember when the Doctor was a fucking fairy!

July 29, 2019 @ 8:59 pm

I think kindness has a lot of potential to be radical and uncomfortable. It can mean speaking harsh truths that the other person needs to hear in order to help them grow, and always siding with the oppressed. It just means the harshness will never devolve into cruelty for cruelty’s sake.

And notably the Doctor distinguishes between “nice” and “kind”. “Nice” for me is tone policing and caring more about appearances than substance. One could argue that Thirteen’s weakness is precisely that she tries so hard to always be nice that she fails to be kind.

July 29, 2019 @ 10:19 pm

That is a great point about the difference between nice and kind. Especially if you go back to Clara’s ending speech in Listen “Fear can make you kind”.

But I still find the speech on the whole disempowering and vapid. Take the previous line, for example, another platitude: “love is always wise”. It really is not. In fact, it is quite harmful to tell kids to love everything because that’s being “wise”. And it is actually fine and right to dislike or even hate things that are oppressive and those who make it so. The opposite of violence (physical, verbal or otherwise), which is perhaps what Moffat is getting at, is not love. This is the kind of language that has been used to vilify any resistance that does not fall on a conservative, centrist paradigm.

Even from a spiritual sense, there are much better ways to frame the basic ethos behind that platitude without making to sound like a trite sermon. And Moffat is very capable (and quite good) of writing moral exhortations in an inspiring but less vapid way, for example the “without reward, without witness”in this series and as I mentioned before, Clara’s speech reworking “fear is a companion”.

July 29, 2019 @ 10:53 pm

You write: “and it is actually fine and right to dislike or even hate things that are oppressive and those who make it so”…

Well, fair enough for things, I suppose, but while you are at full liberty to think otherwise for yourself, not every philosophy, moral system or religion would agree that it can be ‘right’ to hate another human being. Myself, I think determination to thwart harmful behavior doesn’t have to come with wholly negative emotions such as hatred, which by definition make the people on both sides feel worse than they otherwise would.

July 29, 2019 @ 11:35 pm

I think this is exactly one of the problems with that binary categorisation of that speech. Hate is a huge category that spans from the harmful, soul-sucking emotion (and worse a fanatic violent emotion) to something that can motivate change and action.

Anyway, I just feel sad that Capaldi last words was a bunch of “basic”, binary, moral platitudes: “Love everyone, hate no one, okay?” and that too, addressed to the first female Doctor, as if she is really going to be that dumb. AND I think it irritates me mainly because his era was so much more than that. But that’s okay. It does not matter much. The entirety of his era taken as a whole obviously matters much much more than a single, last episode.

July 31, 2019 @ 11:08 am

I think human beings in general more often benefit from being reminded of platitudes than from being given new moral insight (most important new moral insight comes from applying moral platitudes to situations the powers that be didn’t want people to apply them to).

July 29, 2019 @ 10:57 pm

(I should hasten to point out that this is solely a defence of “hate is always foolish”. “Love is always wise” is indeed a daft and potentially dangerous generalization to make in front of children, even if there are high-concept rationalizations in theology and such which could justify it in some frameworks.)

July 30, 2019 @ 7:25 pm

At any rate, I don’t much like the “without hope, without reward” mantra, specifically the “without hope” bit. I’m too much of a consequentialist for that. Wasting one’s energy striving towards an idea of “nice” when you know from the get-go that it’s hopeless and not going to work is not a morally admirable stance in my book, though there are honorable moral systems where it is.

July 29, 2019 @ 7:50 pm

The regeneration speech isn’t great at having a moral position, but I think the era does have a very powerful and nuanced moral stance, it’s just not explicitly summarized in any one speech. It’s “shown not told”.

To me, the overarching theme of the Capaldi era was an extended self-criticism, a re-evaluation of the past of the show, and an attempt to redeem its past moral failures or at least recognize the need to do better. (Twelve’s evident self-loathing is like the in-character reflection of this.)

The through-line runs from Day of the Doctor (first appearance of 12, or at least his eyebrows) declaring that double-genocide is not an acceptable ending to the Time War, all the way to Twice Upon A Time being basically a promise to do better on the sexism front.

In between we have Hell Bent apologizing for the mind-wipe of Donna, Clara’s whole arc re-defining the role of the companion, Magician/Witch re-writing the Davros story to be about mercy, Dark Water/Death in Heaven showing a better way to do the Cybermen and the Master, Bill’s departure being a middle finger to the bury-your-gays trope, etc. etc., add your own examples.

Does the show have all the right answers? Of course not! But a commitment to always questioning your morals, always trying to learn from your past mistakes, knowing that you will screw up sometimes, but always trying to do better anyway… to me that’s a moral stance, and a good one, and that’s what’s great about this era to me. “usually i’m just some time lord who ran away, but on a good day I can be The Doctor” points in this direction. “Without hope, without witness, without reward” points in this direction. But mostly, it’s something the show demonstrated a commitment to doing, rather than saying.

which is why it’s so, so disappointing that, with the Capaldi era having done so much to sharpen its self-critique, to re-define the moral foundations of Dr. Who to be much more solid for the next 50 years, to throw down the gauntlet with the challenge to do better morally…

the show is reborn into the Chibnall era which doesn’t even seem to recognize that there are any such things as moral stances in Dr. Who, at all.

July 30, 2019 @ 2:41 am

The “be kind” line explains so much about the 13th Doctor, and in some ways her characterization seems like it follows naturally from this. The biggest problem with the Chibnall era is that it doesn’t realize her strict adherence to kindness is also her biggest character flaw.

It would be a million times better if it engaged with that idea. It probably won’t. That’s the biggest “no hope” thing I’m personally struggling with re: the show right now. Glad to see I’m not alone.

July 30, 2019 @ 7:29 pm

I don’t think so; as pointed out by mx_mond, the speech distinguished between being “nice” and being “kind” (“always try to be nice, but never fail to be kind”). And just last episode in The Doctor Falls, “being kind” meant Top-Knots giving Bill a mirror so she wouldn’t live a lie; the Doctor’s exhortation of “be kind” to the two Masters meant “stay here and help me kill the Cybermen”. The problem people find with the Thirteenth Doctor of her being too nice to actually fight evil is actually her failing to live up to this part of the speech; she’s flipped things, being always nice even when that comes in the way of her being actually kind, when it should be the reverse.

July 30, 2019 @ 11:10 am

‘Hate is always foolish; love is always wise,’ may not be of much apparent use when fighting fascists, but when it comes to mental fight against the corners of the universe that give rise to fascists I think it has its merits.

I think the studies all show that when it comes to picking people away from fascism, or winning over those who might fall into fascism, kindness and tone policing work better than anger and condemnation. (Not to say that the anger is unjustified or morally wrong. Just that what is morally permissible may not be a wise tactic.) Hatred and anger are good at winning over the waverers on your side and uniting your own side against the common enemy.

Fascisms seem to work: they’re built around the proposition that there is a common enemy and everyone needs to be united against it. Fascist philosophy is grounded in the proposition that the good society is one that fights things.

The problem is then how far and at what stage of emergency non-fascists can use that as a tactic against fascists without legitimising the fascist foundations.

April 17, 2020 @ 4:54 pm

beautifully put.

July 29, 2019 @ 5:35 pm

Tardis Eruditorum really redeemed Moffat for me. You helped me understand what Moffat was trying to do and what his biggest fans enjoy about some of his episodes that I liked least. Pandorica/Big Bang (and most of the Smith era) is still “not for me” but at least I know why people like it. Your writing also got me back into the show for the Capaldi era, and thank you for that, since I’m one of the fans who think Heaven Sent/Hell Bent, and World Enough and Time/Doctor Falls are all among the show’s highest points.

This last season of Eruditorum has been really thought-provoking in terms of the limits of the Capaldi era and what should have followed it / should still follow it. Thank you for writing this.

Also:

:applause:

July 29, 2019 @ 5:44 pm

Although I see why you covered it separately, I think a lot of the complaints about the structure of Twice Upon a Time are answered by treating it not as an individual story, but as the third episode in a three-parter also including World Enough and Time and The Doctor Falls. It’s not a plot, it’s a fluffy little nostalgic epilogue to let off steam between the high-stakes drama and the actual regeneration.

It is, in other words, the Moffat counterpart to the Hero’s Reward bit (is that what it’s called?) in The End of Time, Part II. Except that since End of Time is a two- rather than three-parter, that sequence remained packaged with “exciting” bits like the Master shooting James Bond with lightning and so on. No, the First Doctor didn’t need to be here… but did Captain Jack? Did Alonzo?

As concerns Bradley’s First Doctor, yes, he’s horribly inaccurate and awfully gimmicky, but I can’t bring myself to dislike him because Bradley is just marvelous in the part, both when playing the vaudeville character of a stuffy, but occasionally wily curmudgeon, and in the few more serious bits like his conversation with Bill Potts. I’d go so far as to say that I’d have loved to see Bradley play the Doctor in earnest, as himself. It probably won’t happen now, for a great number of very good reasons. But he still would have been neat, all the same.

I’m more fond of the Doctor’s regeneration speech than you are, but I cannot honestly say how much of that is that it’s a good speech and how much is a mixture of how much I love Capaldi and how much I love The Shepherd’s Boy. Your paragraph about “the Doctor becoming an effing fairy” did make me laugh.

Now, not being a telepath, I cannot vouch that this is what Moffat had in mind. But as for the Doctor reminding his next self that they need to be kind, but not that they need to fight evil — couldn’t that be another “dark Doctor” thing, where the Doctor will always be ready to blow up the monsters, with or without a pre-regeneration reminder, but does have to consciously make an effort to also be kind and not go all Time Lord Victorious?

Also, if I may just once sidestep into the politico-philosophical bits of your argument… I’m probably not going to sound very coherent, but I do want to try before the Eruditorum ends…

I don’t think it’s quite true to say that the philosophy of “be kind, spread love, abhor hate” can’t solve the problem of there actually being villains in the world. It’s just that what should be done with this philosophy is that it would have to be drilled into the heads of the baddies, not repeated endlessly to the already-mostly-good. Granted, the baddies only rarely watch Doctor Who, so Doctor Who may not be a very practical place to be drilling from. But theoretically speaking, I’ll take the Second Doctor plotting to transplant the Human Factor into the Daleks over his ranting about “terrible things which must be fought”, any day.

…Right, well if the Eruditorum’s done for now, good-bye and a thousand more thanks!

July 29, 2019 @ 6:23 pm

I’ve got no particular love for the regeneration speech myself, but surely the “only children can hear your name” thing isn’t meant literally? I figured it was just Moffat’s way letting Capaldi say his own pet theory about the Doctor’s name on-camera while stressing Moffat’s (the version of it that Capaldi first said at the Series 10 screening didn’t mention kids, just humans) sense that Doctor Who is a kid’s show at its heart.

July 29, 2019 @ 6:57 pm

In Moffatt’s penultimate ‘Production Notes’ in DWM, he says that Capaldi ‘realigned’ the Doctor’s speech.

https://www.reddit.com/r/gallifrey/comments/6k8m8f/production_notes_for_doctor_who_magazine_514_the/

I appreciate that it’s two similarly-aged fans writing their own indulgent, long-winded love-letter to the show, and Moffatt writing about Capaldi (rather than one author’s crystallisation of what the Doctor is). And I do love the note-perfect “Doctor, I’ll let you go.”

July 29, 2019 @ 7:02 pm

Oh, and it’s been a while since I checked Gareth Roberts’ tweets, since I’ve been blocked. But I do recall that the guy hates the Doctor’s urges to ‘be kind’. So that’s another reason to like the speech.

July 29, 2019 @ 7:10 pm

It is rather melancholic to see the passionate idealism you once had in the utopian dream of Material Social Progress fade into… not exactly ambivalence but a sort of emotional detachment that wasn’t really there until Chibnall unleash his vision of reactionary-accommodating banality as the new telos point for Doctor Who.

Not that I blame you. Life in general since 2016 has been one long string of naive illusions dispelled and hopes brutally crushed. And it will most likely keep getting worse. As you wrote, “Let’s assumed we are fucked.”

Still maybe we will survive it somehow. After all, a fair amount of people in the mid-80s a.k.a. the last time DW was failing badly thought the end of the world was nigh too after all. Maybe we’ll get a Peter Harness era that will help alchemically bring about a salvation of the Earth and humanity in 2020s if we just keep on grimly persevering for now.

July 30, 2019 @ 9:18 am

If we believe in the Waller-Bridge era it will come.

July 30, 2019 @ 12:08 pm

Not sure how much Waller-Bridge would be interested in the salvation of the world, based on Killing Eve & Fleabag’s interests.

Meanwhile, RTD showed us his version of how a female doctor (played by Jessica Hynes) would storm concentration camps and bring down a government.

July 31, 2019 @ 2:06 am

Yeah, I was interested in El’s take on Years and Years.

July 29, 2019 @ 10:40 pm

Doctor Sandifer.

El

Thank you

July 30, 2019 @ 5:22 am

The problem for me with writing the first doctor the way moffat did is that although he might have been trying to make some grand philosophical point about the doctor, personally I and I know many others also, found it unpleasant to watch and I can imagine it will put others off watching the first doctors era which would be a shame since they would miss out on Barbara who is I think one of the greatest companions the show has ever created.

Beyond that, it’s not clear why the first doctor would have the prejudices of a 1960s English earth man.

It smacks too much of the whole sexist politically incorrect grandpa trope which has become popular over the last few years, where the morral is usually look how crazy those leftist social justice warriors are.

July 31, 2019 @ 11:20 pm

Any chance of making a point with the use of the first Doctor was ruined by the insertion of things that he wouldn’t actually do.

July 30, 2019 @ 7:19 am

As always I enjoyed the read, so, thank you.

This episode is the only one of the rebooted series I don’t think I’ll ever rewatch. I really disliked that much and much of it made me feel actual anger (very rare); especially the casual destruction of the Hartnell doctor for no purpose that I can see other than to highlight the ‘faults’ of the Doctor’s character so the change to the female is seen to emphasise his/her ascending to a higher and more moral being.

It also finally turned my wife off of watching any earlier Who with me. Always a tricky sell, but gone now…

July 30, 2019 @ 9:02 am

I do love that line just before the regeneration speech “Yes, I know they’ll get it all wrong without me.”

So true.

July 30, 2019 @ 9:15 am

Thank you for this great essay. What an amazing ride this has been. Thank you, and I hope your next project brings you much joy.

“Exhaustion” is the first word that comes to my mind when I think about this story. I like it, but as you say, it’s a pleasant mess. There’s barely any plot, the themes don’t quite come together and the characters are all distant and more or less distorted echos of themselves. The Bradley Doctor who is not the First Doctor, the wrong Lethbridge-Stewart and Bill and Nardole who are memories held in glass and act like generic versions of themselves, fully disconnected from their previous story arcs. (And there’s this weird bit where it seems like Bill becomes a stand-in for Susan). In contrast to them the Twelfth Doctor feels most like himself, all grandiose speeches, snarky jokes and S10 tiredness.

Ever since it first aired, I’ve had this funny little reading of this story in my mind where the whole thing is basically the Twelfth Doctor stepping outside of the boundaries of his era and wandering around in the strange liminal space between incarnations (or perhaps his own unconsciousness). There are decrepit ruins of his past everywhere (including the appropriately named Rusty), he doesn’t have a villain to defeat and there’s a transparent, ghostly female figure whose role is to make sure that this unplanned detour ends and history (herstory) gets back on track and who can be thus read as the ghost of the future.

In this reading the First Doctor (or rather, like you say, the idea of the Original Doctor) is a cracked mirror in which the Twelfth Doctor can see some of his own inadequacies, mostly his patronizing nature, his petulant unwillingness to let go of his ego. Twelve is deeply embarassed by this part of himself, but also clearly kinda loves it. The Original Doctor is his reckless and carefree youth, the Doctor from before he defined himself as a hero. For all of his old man ways, the Original Doctor is still full of potential, unburdened by the long and painful history the Testimony shows him. And so a part of Twelve, I think, would really like him to stay as he is forever. Perhaps modernized a bit, with less sexism and cooler eyewear, but fundamentally unchanged. Maybe that’s why the First Doctor is suddenly and anachronistically afraid of regenerating here: if Twice Upon a Time takes place in the Doctor’s unconsciousness, then Twelve is trying to symbolically prevent his entire self, from first to twelfth incarnation, from changing. To freeze himself in time, if you will.

But of course the change cannot be stopped. It’s long overdue anyway; even the Master got there before him. The episode doesn’t give us a definitive answer to the question “why did he eventually choose to regenerate?”, but an answer can be found: it was the women. His female TARDIS took him to a place outside of himself (an out-of-male-body experience), the vision of Bill taught him the importance of letting go, the vision of Clara made him realize how awesome a female Doctor could be and then his TARDIS apparently argued with him in the final scene, eventually managing to convince him to live. And even before that, in The Doctor Falls, it was Bill’s tears and a vision of Missy that revived him when he was lying dead on the floor. The future was indeed all girl. It’s just a shame Chris Chibnall got to write it…

July 30, 2019 @ 11:44 am

It’s a bit of a shame Capaldi’s final speech is two middle aged white blokes (Capaldi/Moffat) mansplaining Dr Who to the next incarnation.

July 30, 2019 @ 12:19 pm

Except that it’s very self-consciously (and very well) performed by Capaldi as a frail old guy who can barely stand up, whose time is up, a hair’s breadth away from senility, talking to himself as a means of encouraging himself to keep going. Before he admits some kind of defeat at being able to hold on to anything, and gives up being him.

August 1, 2019 @ 7:36 am

If you include Moffat amongst the explainers, then I think you need to include Chibnall amongst the explained-to.

July 30, 2019 @ 12:07 pm

Speaking of Russell Davies and politically engaged Doctor Who, how many people saw Years and Years? (I didn’t as I didn’t get on with Davies’ personal style in Doctor Who and Torchwood. But that doesn’t mean I don’t believe it was good.)

July 31, 2019 @ 10:01 pm

It started out great, with amazing character writing, so very RTD.

Halfway through it became horrifying in its brilliance, so very RTD.

It ended being absolute bonkers and silly, so very RTD.

July 31, 2019 @ 11:09 pm

I thought it was like Turn Left done right. (As in ‘correctly’.) It benefits from having enough time to actually show how Britain gets into that state, rather than just having to assert it.

July 30, 2019 @ 1:44 pm

I do have a deep fondness for this episode; in particular, the speech Capaldi gives on the battlefield is stunning. Beautifully performed and a beautiful slice of writing. Haven’t been able to get that speech out of my head since it aired.

July 30, 2019 @ 2:09 pm

The story is almost transparently Moffat writing a story about himself, however fictional. Memoralizing what made his era great (and compromised), not wanting to go but being exhausted unto death, being revisited by the glass figures of all the characters he created as they live in the minds of the rather threatening fandom who insist on running about and collecting everything about every character who appears, taking a visit to check on his predessor Rusty to find that the guy’s a little grouchy and could stand to spend less time on the Internet, and finding a plot twist to save two soldiers’ lives, possibly including a future showrunner who would guarantee El doesn’t return any time soon.

The two glaring flaws, and they are painful ones: Chibnall seems to have listened to the closing advice a little too closely, and they cast David Bradley when they should have cast Jessica Raine. One’s false sexism here is painful in large part because the tale should be about how the first showrunner was a woman and isn’t it about time the Doctor is, too? But in the end, Moffat proves unable to escape the old white man of his past. We’ll see if the show he left behind manages better.

Until the next adventure, friends. Thanks, El.

July 30, 2019 @ 7:33 pm

“taking a visit to check on his predecessor Rusty to find that the guy’s a little grouchy and could stand to spend less time on the Internet,”

Oh my word, I never noticed that. Mind you, not sure how intentional it is, since apparently the name derives from what some fans were nicknaming the Dalek in Dalek; but this is still hilarious.

July 31, 2019 @ 2:20 am

“the tale should be about how the first showrunner was a woman and isn’t it about time the Doctor is, too?”

I disagree. That tale should be about how the first showrunner was a woman, and isn’t it about time the new showrunner is, too. Which is a tale to be enacted on a different stage.

July 30, 2019 @ 4:09 pm

For what it’s worth, I quite liked the episode. It’s self-indulgent, but I’ve never been against that. I suspect it’s an extension of Moffat’s ‘give the departing actor their favourite monster to go out on’ except with himself, his favourite actor and his best friend, which does make it a tiny bit messy. The farewell speech in particular (which did make me cry at the time) was maybe a bit muddled because it had two authors, possibly three if it had to be looked over by Chibnall’s team, but presumably had to be kept reasonably tame in case the next doctor didn’t live up to anything more radical. (One of the recurring things I see said about Whittaker’s Doctor is she followed 12’s advice), but in the end, Capaldi’s Doctor’s arc has always been about kindness, which i took to mean, always do the right thing even if it’s hard, even if it will kill you in the end, which is far from toothless.

The episode as a whole is also pretty easy to read as a passing of the torch in a way other regeneration stories aren’t so much. I suspect I might be paraphrasing your review to read Bradley Hartnell as early Moffat and Capaldi as late Moffat, but it does feel like he’s saying to Chibnall, ‘I’ve done all I can, but look how far I’ve come. Keep up the good fight.’

July 31, 2019 @ 1:43 am

“What do you mean, ‘One’?”

♥

July 31, 2019 @ 8:03 am

I love that bit. And it nicely parallells the First Doctor’s relative innocence compared to the Twelfth Doctor, and why he looks so scared after Testimony shows him his future.

August 6, 2019 @ 6:39 pm

I found the comment Paul Cornell made about his novelization of TUAT (which I haven’t read yet) similar to something you said: “I made some changes to the shape of the story. I thought that a piece that started off with both Doctors not wanting to regenerate really should indicate when and how they changed their minds about that. I felt strongly that that was the journey the story seemingly sent them on, only never to quite resolve that central question. So I did it, adding points along the way to make that journey smooth and central.”

It’s a weird choice on Moffat’s part, and I’m not sure I get it.

August 7, 2019 @ 9:02 am

Paul Cornell certainly answered that question better than Moffat, and that’s good. Other than that, unfortunately I found the book quite dull. It didn’t add much to the story as told on TV, unlike RTD’s or Moffat’s novelisations.

August 9, 2019 @ 12:02 pm

I really love the comment above from David where’s he sees the story as being about Moffat writing about himself. I can really see it.

I feel sort of sad feeling not only this run of the Eruditorum ending, but also reading (and agreeing!) that Doctor Who currently feels like it is not meeting and bowing under “the horrors of the 21st Century”.

Thank you so much El.

January 16, 2025 @ 3:15 pm

Sorry for messaging from the future but Russell T. Davies might not have been as done as we all thought.