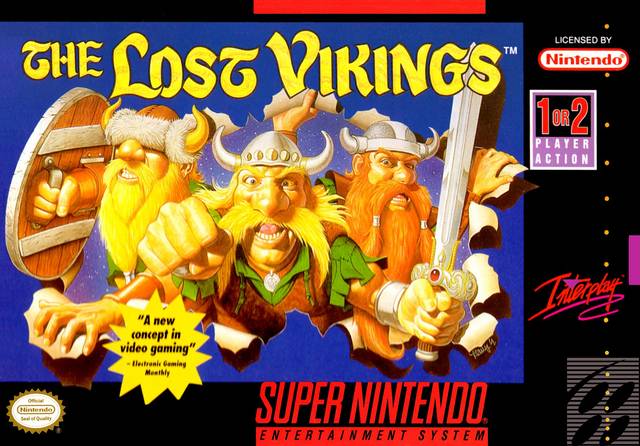

Thought and Memory (The Lost Vikings)

They are, in truth, not lost, although they have gone far more astray than even Vinland. Were one to locate it on a map of genre, it would rest near Lemmings in the genre of action-puzzle. Like Lemmings, it is a game about navigating some characters through a series of traps to a goal. Also like Lemmings the characters are each given unique abilities. There are major differences – Lemmings’ central mechanic is based on the idea that the Lemmings are going to behave the same regardless of what you do, and on assigning special abilities to specific Lemmings at the right time, whereas The Lost Vikings gives you a trio of norsemen, each with their own special abilities, and has you alternate among controlling them. But the basic mechanic is the same.

They are, in truth, not lost, although they have gone far more astray than even Vinland. Were one to locate it on a map of genre, it would rest near Lemmings in the genre of action-puzzle. Like Lemmings, it is a game about navigating some characters through a series of traps to a goal. Also like Lemmings the characters are each given unique abilities. There are major differences – Lemmings’ central mechanic is based on the idea that the Lemmings are going to behave the same regardless of what you do, and on assigning special abilities to specific Lemmings at the right time, whereas The Lost Vikings gives you a trio of norsemen, each with their own special abilities, and has you alternate among controlling them. But the basic mechanic is the same.

First is Eric, swiftest of the Vikings, and the only one who can jump. Nominally, this means that he is the one with whom one explores the level to figure out what you’re supposed to do. And in this, he represents a crucial drive. Indeed, exploration is one of the basic types of gameplay in some models of how players interact with games, and it’s certainly one of the basic psychochronographic drives.

This is, perhaps, inherited from psychogeography, which is, after all, first and foremost a means of exploration. Although in both cases (as with Eric) it is not pure exploration, which is to say, it is not driven simply by a desire to find something that is new. Instead it is exploration in pursuit of a goal – a promised land, of sorts. The literalness of this shifts in context – Eric, for instance, very literally seeks a new land with every level, that being what an exit is. Similarly, the psychogeographer’s quest is necessarily defined by the physicality of land, even as they seek to conceptually reconfigure it, as opposed to abandoning it in favor of a new place. The psychochronographer, meanwhile, does not explore land in the conventional sense at all, instead looking for new modes of being and ideas.

In every case the pursuit is at its heart a tragedy. To find the promised land is always to despoil it. The psychochonorapher finds a new idea only to have it snap into place with relation to all other ideas, to become a spot on the psychic map like any other. The psychogeographer reconfigures space to his whims only to see it endlessly recuperated as the oppressive ordering of things takes hold. And even Eric will find that every exit is, in reality, simply an entrance to another map. Discovery is and always will be the death of exploration.

Although that one’s a bit dodgier with relation to The Lost Vikings. This is not so much because discovery is not the death of exploration as because there’s just so many other ways to die. The traps, generally speaking, aren’t a huge problem for Eric – more often than not, with his ability to jump, he’s actually the one who’s supposed to navigate those. No, it’s the monsters that prove difficult for him. Far too often exploration is cut tragically short when one runs smack into a monster.

For that there is the second of the Vikings, Baelog, who wields both sword and bow. In this he is a common archetype, again linked to a fundamental mode of gameplay. And like exploration, there is something primal about it. Indeed, there are worldviews in which this is not merely a fundamental mode of gameplay, but an axiomatic truth about the nature of life – the Darwinian struggle and all that. So it is hardly a surprise that it is one of the foundational dynamics of video games. The overwhelming majority involve smashing enemies of some sort.

Although it is in some ways strange that this should be a part of The Lost Vikings. The monsters do not provide a great challenge, certainly. That’s not to say they are not frequent causes of player death; they are, especially when they are unexpectedly encountered. But they are challenging like the existence of other cars on the road is challenging, which is to say, they’re only a problem if you deviate from correct operating procedure. (Although, of course, with cars the goal is to avoid smashing.)

But correct operating procedure requires a measure of knowledge. This is the most basic rule of the algorithm: output is merely a response to input. Cars avoid smashing because of a massive network of signals that inform their drivers of where to expect other cars to be and what to expect those cars to do. Baelog succeeds in it because of a similarly massive network of signals that informs his player of where to expect monsters to be and what to expect their behavior to be.

Except, of course, that The Lost Vikings carefully obstructs this knowledge. That’s what the necessity for exploration means. And it’s not just the likelihood of Baelog happening to not be the Viking you’re controlling when you run into a monster. Many monsters, especially those with ranged attacks, are not straightforward for Baelog to take down unharmed.

This brings us to the third figure, Olaf, who wields a shield. This is, off the bat, generally something of a necessity with monsters, with the correct strategy for dealing with them generally being to have Baelog stand behind Olaf’s shield and pummel them.

This would seem, then, to complete a certain train of thought. Unlike Eric and Baelog, Olaf can map out the world safely. But it is telling that Olaf, unlike Eric and Baelog, does not represent a fundamental mode of gameplay. People play games to explore or to whack things. Nobody plays games to stand still as the inviolate and unyielding shield that guards other people.

Out of this perversity arises the central challenge of The Lost Vikings – one that is not an entirely pleasant and fair one. Simply put, you’re engaged in a sort of continual leap of faith, plunging forward with one character or another only to discover you’ve picked the wrong one, dying, and having to replay sections. And the easiest way to avoid this – to simply always lead with Olaf until it becomes clear you need someone else – is simply put, boring.

The result is a game that’s ever so slightly disappointing; one where there seems constantly to be a good game about to start, but that oddly drifts further and further away from it as the levels get more elaborate and the amount of time spent replaying the same opening sections of them grows. On top of that, there’s a slowness to it – an awful lot of time is spent running your second and third Vikings down corridors already traversed by your first one. It is, in other words, a game that irritatingly withholds the fun.

There is an insidious moral endpoint here – one suited to the market in which Lost Vikings maker Silicon and Synapse eventually found its most enduring success in – based on the penalization of fun. The Lost Vikings is unquestionably more entertaining if you simply charge forward with Eric at maximum speed, or decide to wade into combat with Baelog unprotected by Olaf’s shield. Or, at least, it would be if that didn’t mean endlessly dying and replaying sections.

Two obvious exits present themselves from this position. The first is what we might call a redemptive reading of Olaf – one in which we try to redeem the defensive position as an aspirational alternative to exploring or fighting. This, however, seems to me fundamentally lacking. It is not that there’s nothing to be said for the idea of the shield. Rather, it’s that the underlying tension between it and the video game is irreducible. The shield is simply not a way we play video games. It does not fit into the conceptual world being built.

So we are left with the alternative – to accept Olaf as a fundamental travesty of a character whose existence goes against the basic nature of what video games are. Which makes sense. The act of erecting a shield – of steadfastly and absolutely resisting change – is antithetical to the process of playing a video game, whereby one allows one’s self to be taken over and changed. And moreover, this is the part of video games that offers the greatest redemptive possibilities. Olaf’s rejection of it in favor of standing as an unchanging and impermeable wall isn’t just boring; it’s antithetical to the very power of video games.

October 5, 2015 @ 8:11 pm

I’m getting the feeling this column is building toward some dread resolution. The next great gaming collapse which every critic sees coming, maybe. Or something even more unspeakable….motion controls.

October 5, 2015 @ 9:02 pm

I find it very interesting that they use the phrase “Not Your Shield”. Interesting in that the phrase implies that the speaker is the shield of someone else rather than not being a shield at all. Of course, this all ties back to the fundamental concept of ownership of space within the GG community in that the GG community owns the shield. In turn this connects to the character of Vivian James, a shield in her own fictional nature who also acts as the model for other shields of her brand. One has to wonder why someone would want to be a shield who, as Phil mentioned, deliberately chooses to stand still and never change on their own accord. What sort of person would attempt to reject the natural order of the world for the sake of their own egotism? And then I remember that Vox Day thinks death is a form of evil and suddenly the world of the GG makes perfect sense.

October 5, 2015 @ 10:00 pm

I almost made this a shaggy dog entry that ended on a “not your shield” joke.

October 6, 2015 @ 5:25 am

“The result is a game that’s ever so slightly disappointing”

NO! NEVER!