Tricky Dicky, Part 7: Vanilla History

NOTE: This article has been amended to remove factual errors (please see the comments).

NOTE: This article has been amended to remove factual errors (please see the comments).

It used to be said that Englishmen got their understanding of history from Shakespeare and their understanding of theology from Milton. These days, they get their understanding of history from Simon Schama and their understanding of theology from Richard Dawkins. God help us. In practice, this means middlebrow television and middlebrow publishing. Which could, at the moment, with a little stretching, be boiled down satisfactorily to one quasi-word: BBC.

Shakespeare, meanwhile, has gone largely from being a purveyor of an idea of history to being a bit of history that is itself purveyed. It’s no secret that he’s an industry all to himself. Of course, what that actually means is that he’s become an idea people sell – and part and parcel of this idea is a whole complex of other ideas, some of which are still about the history he supposedly tells or implies. Like any industry, the packaging is as much ideological as it is plastic and cardboard. And when it comes to the ideological packaging of isolated, decontextualised, atomised, rendered, pulped and puréed chunks of Heritage Themepark British History, the BBC is, once again, the main nozzle through which the resultant gloop is shat into the nation’s collective kingsize Styrofoam goblet.

This is certainly true right at the moment, during the second season of The Hollow Crown, the BBC’s glossy adaptation of Shakespeare’s main cycle of history plays, and in the immediate aftermath of the RSC’s and BBC’s Shakespeare Live! event. Yes, they put an exclamation mark at the end. They did. This gala, star-studded barrowfull of bardballs was perpetrated supposedly to commemorate the 400th anniversary of Shakespeare’s death. I still don’t understand the idea of celebrating the death of someone you supposedly admire… except that I do understand it, of course: it’s a populist and sentimental way of conferring ostensible meaning on a random date, meaning which can then be parlayed into marketable goods, services, and/or ideological products.

Speaking of marketable ideological products, I was going to talk more about Shakespeare Live! but… it had Prince Charles in it, which made talking about it pretty much superfluous. He appeared in a playful little skit with some actors… and that’s all that really needs to be said. This alone tells you literally everything you need to know.

Prince Charles, you see, is like a black hole. Not in the sense of being cosmically impressive, but rather in the sense that his mere proximity pulls in and crushes all other meanings into mush. He is a meaning-pulper. He is so empty, yet powerful (not because of anything he does but simply by having come into existence as a massive negation with intense cultural gravitational pull) that any context into which he is inserted instantly becomes about having him in it… which is functionally the same as being drained of all substance. Because he has none. Like all modern British royalty, he simply is what he is, and what he is is nothing more than the position he occupies by accident of existence.

It’s not unlike when Tony Blair did a sketch with Catherine Tate during Comic Relief (or Children in Need, or whichever revolting orgy of establishment-endorsed sanctimony and sentimentality and rationed-compassion it happened to be) not long after the invasion of Iraq. His very presence in the show sucked out all other possible meanings – including the almost-certainly good intentions of Tate – and turned the entire event into a big frilly bow tied around a vast pile of rotting, dismembered corpses. Probably the corpses of children in need of burial after Tony Blair had lots of bombs dropped on them. (Was he bovvered? Did his face look bovvered?) The difference was that there it was Tony Blair’s subjectivity (that of a war criminal) that drained meaning out of its surroundings; with Charles Windsor, it was his objectivity. I’m not saying he’s impartial; I’m saying he’s an object.

So Charles sucks every other possible meaning out of Shakespeare Live! simply by being there, himself, in all his vacuous, meaningless Prince Charles-ness, surrounded by actors playing at playing Hamlet, and all of them yucking about how rib-tickling it is to have a prince (“An actual real-life prince!” they seem to say, as starstruck as Joe Schmo might be upon meeting them) on stage playing a prince, surrounded by people playing a prince. The real irony is not the irony everyone is yuck-yucking at. The real irony is that, centuries after Shakespeare used prince Hamlet to express the rise of a new subjectivity in humanity, a different prince (an actual real-life one… well, sort of) stands amidst a crowd of Hamlets sucking away their subjectivity by way of his own lack of same. (Readers of Part 3 of this series will understand the historical context in which I view this irony, and I hope to develop it with regards the Windsors and their ancestors – sometimes called the ‘Norman Yoke’ – in later Parts.)

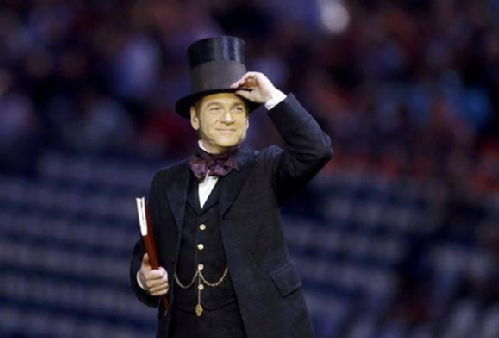

We can’t (since we seem to be going into this after all) pass over the matter of the Olympics. The matter of bloody Kenneth bloody Branagh reciting Caliban’s speech about the island. Let’s be clear about this: that speech is not about the British isles. It’s not about how beautiful and magical and paradisical greenandpleasantland™ Britain is. It’s the speech of a conquered native about his own occupied island, an island invaded by Europeans who have made him a slave. Whatever problems there may be with Caliban (and boy howdy are there perrrrr-oblems) he has been understood (or appropriated if you like, it makes no real difference here) by generations of people in the colonial and post-colonial world, as a figure representing their own experience as the original inhabitants of lands invaded and subjugated by European imperialists. This is not a misreading of the play, or even a stretch. Whatever those above-mentioned perrrrr-oblems, Shakespeare does at least know what he’s referring to. But in the fucking Olympics, Kenneth fucking Branagh delivers (or steals, if you prefer – because I certainly do) Caliban’s speech about his own natural connection to, and love of, his home, and delivers it as if it were about glorious Britain, while – and here’s the kicker – dressed as Isambard Kingdom fucking Brunel, the epitome of the Victorian gentleman of the Industrial Revolution. The Industrial Revolution was also the golden age of British imperialism, when a quarter of the globe was pink with the semi-washed-out bloodstains of untold numbers of Britain’s ‘subjects’. I’m not averse to adapting Shakespeare’s words to new contexts, but there is a line in the sand of the context which, once crossed, becomes egregious. It’s been four years and I still can’t get the filthy taste of that one out of my mouth. It only makes it worse that Branagh is actually from Northern Ireland. I mean… fuck.

It’s not as if there are no patriotic puff-speeches in Shakespeare that are actually about the British isles that they could’ve used, even some not coming from the mouths of slaves (thus making them far more suitable for the spectacle of power that is the Olympics). I’m sure they could’ve gotten away with adapting the “this sceptre’d isle” speech of John of Gaunt in Richard II without someone in the stadium audience standing up and saying “er, excuse me, this is actually Gaunt complaining – anachronistically, by the way – about how great England used to be before capitalism started primitively accumulating feudal property…”

Let’s move on from these blithering obviousnesses. You take my point, I hope.

Let’s instead examine my first statement a bit more closely. Let’s start by doing that annoying thing where we quibble over what words mean. This is worth doing, I think. Slippery little fuckers, words. One word in particular seems to need looking at sternly and quizzically: ‘Englishman’. What is an ‘Englishman’?

Well, tabling the issue of erasing more than half the population, the obvious answer at the moment, as far as most of the world seems to be concerned, seems to be: Benedict Cumberbatch. And, by ‘Benedict Cumberbatch’, I of course mean ‘any of that assortment of bland, largely interchangeable white British actors currently enjoying inexplicably high-degrees of visibility in global media culture’. You know the ones. Tom Hiddleston, Michael Fassbender, James McAvoy, Martin Freeman, et al. That lot. (Bad at what they do? No. Deserving of their special status? Again, no. I mean, c’mon… Freeman gives essentially exactly the same performance in everything he’s in. Tell me I’m wrong.)

But to pick on Cumberbatch a bit. He was one of those actors yucking sycophantically around Charles Windsor. He goes from balling out theatre audiences about the evils of anti-refugee politicians to creeping round the royal rectum seemingly without a breath. Cumberbatch is an interesting figure for us in this series because his performance as Richard of Gloucester (later Richard III) is currently airing on BBC1 in The Hollow Crown. He is also, as the media has fallen over itself to remind us, ostensibly a descendant of the historical Richard… which was the pretext for him reading the Poet Laureate’s ‘poem’ about Richard III at Richard III’s (we think… probably…) long-delayed state funeral last year.* Cumberbatch has been asked how he feels about playing his ancestor. What he says needn’t detain us. What’s interesting is the implicit assumption that he’ll have something substantive to say. At least on some level, we are still expecting to be taught history via Shakespeare – and we’re still expecting to be taught by an ‘Englishman’, even if we don’t all identify that way ourselves. I, for instance, only ever self-identify as an ‘Englishman’ in an ironical context (I’ve done it during this series) though I’m eminently eligible by the standards of, say, UKIP. (Yes, we’re going there.) I am, of course, white. I’m about as white as it’s possible for a man to be without actually being made of snow.

It’s an interesting question to what extent the Early Modern dramatists themselves might have considered themselves historians or accurate purveyors of history. I suspect their attitude was probably quite like that of today’s actors and writers: they didn’t have a set and coherent position because they didn’t really differentiate between their priorities and the priorities of their ostensible subjects, nor between ‘accuracy’ and ‘plausibility’… a form of what has been called ‘truthiness’.

Certainly, we know of plays from the time being praised by contemporary critics for ‘bringing the past to life’. Henry VI Part 1 (or ‘The Hollow Crown S02E01’ as we’d probably call it now) seems to be one such play. A contemporary writer praised the way a theatre audience seemed so wrapped up in the fate of Talbot (a national hero for his efforts to keep France bloodily subjugated to English rule… though these things weren’t as simple as that makes them sound, what with dynastic politics and so on) that Talbot, long dead even at the time, seemed to come alive again in the present. You can never be sure that the writer isn’t just spouting rubbish (oi, watch it) or that his view represents a widespread feeling, or even that he’s talking about the play we now call Shakespeare’s Henry VI Part 1. There might’ve been others about Talbot. The reviewer doesn’t specify the playwright responsible for what he saw since writers weren’t (even) what they are now, and indeed the play we now call ‘Shakespeare’s’ Henry VI Part 1 was almost certainly written by a consortium of jobbing hacks of which Shakespeare was but one. All the same, contemporary audiences seem, at least in some way, to have considered that they were watching a representation of things that actually happened. If they understood that they were also watching commentaries on their own Now (and they totally did) then once again, that’s not so different to how we interact with texts about ‘the past’ today.

But there was also politics. Open, material politics. Powerplay. I mean, of course there was. Richard II, for instance, was a political football of a play because it dealt with a king who gives up the crown under pressure from his rebellious nobles (in the incendiary ‘deposition’ scene). Indeed, Richard II was a king much talked about in the anxious latter days of Elizabeth’s reign, as people fretted over the possible return of dynastic wars (i.e. a new bout of the Wars of the Roses) when the Queen died without a direct heir. One man was persecuted by Elizabeth’s state for publishing a pamphlet in which he openly compared Elizabeth to Richard II (a comparison she herself is anecdotally supposed to have made). The legend is that Shakespeare’s play on Richard II was used by disaffected aristocrats to try to put pressure on Elizabeth – who was vastly unpopular for most of her reign, contrary to the Gloriana myth – to resign and hand the top job over to a dude with a better line of succession. Ostensibly, Shakespeare’s company was paid by the Earl of Essex’s men to perform the play before Essex’s rebellion to whip up public feeling. This story is often recounted in biogs of Shakespeare but makes no sense to me at all – but we’ll let that pass.

Recently, some obscure UKIP wankstain had a twitterwhinge about the habitually excellent Sophie Okenedo playing Margaret of Anjou in The Hollow Crown. His complaint was that it violated ‘historical accuracy’ to depict Margaret as a black woman. He got himself amusingly schooled by an actual historian, who pointed out to him that the picture of a white Margaret he used as a comparison with Sophie Okenedo is from a medieval illuminated manuscript in which it is claimed that Margaret was descended from a magic swan. Any swan-related actresses on the books at Equity? If so, they really should’ve gotten the job… which I guess would be okay with UKIP because the half-swan/half-actress hybrid would presumably be both very white and owned by the Queen.

It’s the most obvious thing in the world to point out the massive, clanking, swaggering, empty-headed hypocrisy at work here. And I shall. For instance, the obnoxious UKIP dickferret’s ostensible concern with ‘historical accuracy’ doesn’t extend to the fact that the characters in the Henry VI plays (in which Margaret is a main character) speak to each other in apparently spontaneous iambic pentameter**, much as characters in Hollywood musicals spontaneously break into song, accompanied by invisible orchestras, and nobody bats an eyelid. Nor does he appear worried by the unlikely way they tend to end speeches with memorable, zinging rhyming couplets. Nor does he appear bothered about the vast number of anachronisms and historical howlers with which Shakespeare’s history plays are littered.

The current series of The Hollow Crown is made up of Shakespeare’s First Tetralogy of history plays (the three parts of Henry VI and Richard III) and tells of the Wars of the Roses. The Second Tetralogy of history plays (Richard II, Henry IV Parts 1 & 2, Henry V) are essentially prequels, and tell of events before the Wars of the Roses… and yet have their characters displaying an almost clairvoyant anxiety about the possibility of the Wars of the Roses starting – almost as if the plays were written by playwrights (plural – as I say, some of them are almost certainly collaborations) living after the Wars of the Roses, in a culture in which the ruling classes and their ideologues constantly used the recurrence of the Wars of the Roses as a threat with which to browbeat their subjects into accepting the current monarchical establishment, and in which the public fretted constantly about the uncertain succession via obsessing over the Wars of the Roses…

The tweeting UKIP twit seems mysteriously unbothered by the historical doubtfulness of people knowing about the Wars of the Roses before they happened. Similarly, he doesn’t seem bothered by the psychic foreknowledge of subsequent events displayed at the birth of baby Elizabeth at the end of Henry VIII (which Shakespeare co-wrote at the end of his career with John Fletcher). Nor does the faracical little UKIP bumballoon seem put-out about the fact that Shakespeare’s characters, for some reason, speak to each other in Early Modern English in medieval Elsinore, ancient Rome, ancient Egypt… On the subject of which: why is there no record of the UKIP pissweasel being upset when Cleopatra – who was not only, y’know, African, but who is explicitly described as a woman of colour in the text – is played by Helen Mirren or Jane Lapotaire or Janet Suzman or Zoe Wanamaker? (And that’s just Cleopatra as written by Shakespeare.) The unwashed UKIP vas deferens seems unpeturbed by Shakespeare putting mechanical clocks and Early Modern English clothing laws into the Rome of Caesar and Brutus, or by Shakespeare’s claim that Bohemia has a coast despite the fact that – out here in the real world, where it was roughly what we now call the Czech Republic – it’s landlocked. (He says it has a desert too, as it goes. And bears. And, by at least a superficial reading of The Winter’s Tale, statues that come to life.) The UKIP fucktrumpet doesn’t seem bothered by various cross-dressing plots which defy ordinary conceptions of what constitutes probability, or by stories which end when literal gods descend from the sky to sort things out. Tthis unambiguously happens in at least two Shakespeare plays I can think of off the top of my head, and might happen in a third depending on what we do or don’t interpret as a dream.

Getting back to the plays currently getting screentime as series 2 of The Hollow Crown, the sweltering UKIP douchenozzle is apparently unfazed, his sense of ‘historical accuracy’ left un-outraged, by the various ways in which the Henry VI plays defy credibility, i.e. functioning witchcraft and accurate prophecy, Henry VI himself predicting the ascension of Richmond (the future Henry VII) despite the fact that nobody at the time seriously dreamt of such a thing happening (except Richmond’s power-hungry mum, Margaret Beaufort).

I haven’t watched this season of The Hollow Crown yet, so I don’t know if the actors are looking at the camera to address their solo speeches to the audience the way they’re supposed to (I’m guessing probably not), but that is undoubtedly what the writers expected and the original actors did. Are we to understand it as ‘historically accurate’ that Warwick would address a long speech about his own death to a crowd of invisible people while in the process of dying?

But Margaret of Anjou played by a black actress? This worries the UKIP arsetrumpet.

You know, I may sound cynical, but it’s almost as if there’s a massive great hypocritical double-standard at work here, and the axis of the double-standard is skin colour.*** If he doesn’t know about the other violations of ‘accuracy’ that fill Shakespeare (and there’s no shame in not knowing about it if it’s not your thing) then he should probably keep his trap shut. But the very fact that he’s a UKIP councillor informs us that he’s not the sort of person to refrain from offering loud opinions based on his ideas of plausibility and nothing more, i.e. his own ignorant prejudices.

As I say, our whole concept of ‘accuracy’, be it in Shakespeare, in representations of the past or the present, is actually more like that kind of ‘plausibility’ – and what we find plausible is always going to owe a huge amount to the ideology we have imbibed and learned to take for granted. A huge part of what the racist UKIP turdwit tweet-avenger considers ‘accurate’ (i.e. plausible) is going to come from how he learned history, and who from, etc. As is so often the case with fring reactionaries, they’re just partaking of something pretty mainstream in a loud, extreme, and truculent way. This is the essence of Right-wing populism. Swaggeringly declare the ‘common sense’ that appeals as being plausible (i.e. confirming of self-serving prejudices) of a disaffected mass in the squeezed middle. We see a lot of it about these days, bewigged and orange-hued or otherwise.

Sadly, there’s still more than grain of truth in the idea that ‘Englishmen’ (and surely the UKIP fartbucket in question would proudly self-define as such… not, by the way, that I mean to lump Cumberbatch in with him as a kindred spirit…) learned their history from Shakespeare. That’s to say: Shakespeare as he has been understood, interpreted, and represented by generations of actors, directors and producers working within the enveloping hegemony of white-supremacist ideology generated by, and supporting, British capitalist imperialism. As I never grow tired of saying: you don’t have to believe it for it to work. It just has to seem like common sense. Truthy. Plausible. Normal. Unexceptionable. White. White nearly all the way down. That’s enough, all by itself, for it to migrate – in the minds of many at least – into the category of the ‘accurate’.

It’s only comparatively very recently that the British theatrical establishment / Shakespeare-industry has started to deconstruct and buck this trend… which is why it seems to some like an assault on the ‘normal’ (and, by induction, the ‘accurate’) when it happens. It will take a long time for Shakespeare, as writer or genre or institution, to shake off the encrusted filth of its historico-ideological appropriation by white supremacist British capitalist imperialism. The irony is that, even then, it will be far from delivered of having to perform ideological functions which bolster the status quo in some way. Even the colour-blind casting of today (laudable as it is) serves to legtimate a certain view of Shakespeare as liberatory in terms of our ostensibly enlightened modern liberalism. ‘Our’ heritage is employed to break down barriers and express ‘our’ post-racial society, etc. The promise of egalitarianism is thus spuriously implied to exist within the hegemonic and prestigious texts of the English literary and cultural ‘canon’. We’ve always been modern, enlightened liberals – Shakespare, our native genius (etc etc) knew it, and now we’re just catching up with him. This is also, of course, how the Prince of Wales can wander on stage and yuck-yuck with lefty actors. The Bard supposedly helps us break down these hierarchies and laugh about them. How unfair can ‘our’ society really be when Sophie Okenedo plays a Queen in a prestigious, glossy BBC production of the history plays that have been called our ‘national pageant’, and an actual real-life prince comes on stage to banter with Dame Judi? The UKIP meathead’s crass expression of racial anxiety isn’t actually a problem here, but rather a constitutive contradiction that helps throw the supposed solution we’ve all arrived at (together!) into relief.

Shakespeare is still teaching ‘Englishmen’ their history. Shakespeare’s actual acute observations of the paradoxes evident at the proto-birth of capitalist imperialism are effaced as a natural part of this process. The genuine howling snarl of resentment that is Caliban’s becomes Branagh/Brunel’s paen to Britain, in an orgy of corporate-sponsored and specisoulsy-progressive patriotic cheerleading, based on the meritocracy of sport and ‘our’ great achivements, like the NHS and post-racism, and all that lovely stuff. Apparently, Shakespeare, as packaged by the institutionally creepy RSC and the even creepier BBC, is now telling us that even after all the years he’s been part of the ideological apparatus of racism and empire, he was actually on the side of fairness and equality and the little guy all along.

We all were really, weren’t we?

That’s the history we learn from Shakespeare now.

To be continued…

* Richard III would’ve had a funeral of some sorts that sufficed to gain him entry to Catholic Heaven at the time of his original burial. The people of his era were quite fussy about that sort of thing… at least, those who could afford to be fussy were.

** …which, just in case you don’t know, is really easy… it’s basically just a line with ten syllables divided into five sets of two (or ‘iambs’), [THIS BIT HAS BEEN AMENDED, SEE COMMENTS] like so:

She-wolf / of France, / but worse / than wolves / of France,

di dum / di dum / di dum / di dum / di dum

(The Duke of York describes Queen Margaret in Henry VI, Part 3)

…so five ‘iambs’ to a line, hence ‘pentameter’…

…it was the dominant form in the theatre of Shakespeare, possibly because it is the form of verse which corresponds most closely to the rhythms of human speech, not least because of how long we can go between breaths, which may also be linked to the rhythm of our heartbeats…

…and don’t worry if you encounter lines that don’t work exactly like what I’ve quoted above. Iambic pentameter, especially in the later and more stylistically sophisticated Shakespeare, is a skeleton rather than a cage.

*** There’s a sense in which both the BBC and Shakespeare – and BBC Shakespeare – have made rods for their own back here. The BBC’s Complete Dramatic Works of William Shakespeare series, for instance, previously discussed in this series, which ran from 1978 to 1985, features barely a black face in all 36 productions. Off the top of my head I can only remember one: Hugh Quarshie is allowed to play Aaron in Titus Andronicus. (Othello is played by an eyeball-rolling Anthony Hopkins in grotesque blackface – it has to be seen to be believed.) But I hope to expand on the co-optation of Shakespeare as ideology by British imperialism in later Parts, and also on the BBC’s role in propagating this ideological co-optation in the twentieth century. Even The Hollow Crown itself, in common with many cinematic Shakespeare adaptations, almost invites the ukippian critique of ‘inaccuracy’ by it’s spurious ‘realism’… but that’s (yet) another essay. (C.f. the bit above where I said they probably don’t look at the audience the way they’re supposed to.)

May 19, 2016 @ 12:22 pm

in which the stress is usually on the ‘iamb’, which is the second of each group of two syllables

Uh, not quite. The iamb is the unstressed and stressed syllables together, not just the stressed one.

May 19, 2016 @ 12:44 pm

Yes, you’re right. Badly expressed on my part.

May 19, 2016 @ 1:56 pm

Interesting point about Cleopatra VII Philopator:

She was the direct descendant of the Macedonian general Ptolomy, and, as far as “race” is concerned, was about as African as Marc Antony (the Ptolemaic dynasty was famously incestuous). However she was born in Africa, and therefore should be considered African. But odds are she was as white as any Macedonian.

Shakespeare giving her dark skin is a brilliant bit of race bent casting from 600 years in the past, and give us a lovely little puzzle: do we go with the text, or do we try for historical accuracy? Does it matter, if the actress or actor is performing the role credibly?

May 19, 2016 @ 3:00 pm

Her mother was a native Egyptian, wasn’t she? Or have I been misinformed? (Quite possible, of course.)

Besides, I didn’t say she was ‘black’, I said she was African, and a person of colour in Shakespeare’s play.

May 23, 2016 @ 2:48 am

Her mother and father were full siblings. Their parents were Ptolemy IX and a slave of unknown origin, who could have been Egyptian or sub-Saharan African or Greek or just about anything else.

May 19, 2016 @ 3:04 pm

Okay, I’ve looked this up and there’s some (seemingly unresolvable) debate. In any case, most modern productions of the play have erred on the side of Cleopatra being white, putting the historical plausibility of that entirely to one side without a qualm, so I think my point stands – but thanks for the interesting qualification!

May 19, 2016 @ 6:50 pm

Absolutely! Happy to contribute

If anything, I think the ambiguity strengthens your point, rather than weakens it.

(Fuck the UKIP)

May 20, 2016 @ 12:32 am

She was probably more Mediterranean than black or native Egyptian (Whatever that meant at the time, at the moment I think the skintones can vary greatly within Egypt), especially with the real and potential inbreeding, but another fascinating caveat is how she deliberately positioned herself with the natives culturally and politically, against her brother and the courtiers that favored him over her politically. Also, to the Romans she’d’ve been fairly foregin, which is also how she’s depicted all over our Western Media. [1]

Also, there’s all the fascinating meanings of being an African: a Roman term I’m not sure Cleopatra would have readily identified herself as, above being Egyptian and Hellenic/Macedonian, and as a term, it refers to a massively diverse group of peoples, of various different extractions and cultures, a majority perhaps being “black” but more importantly to them in their contexts as being whatever ethnicity or nationality they are.

[1] I’m dimly recalling. I could be very wrong.

May 19, 2016 @ 8:50 pm

While the cultural trends responsible for his rise to fame may well be similar, Michael Fassbender certainly isn’t an Englishman – he’s half-Irish, half-German, and considering that he’s played Bobby Sands he’d probably take issue with the conflation.

That aside, great piece.

May 20, 2016 @ 7:49 am

When I rewrite this for the book version I’ll make it clearer that I’m not actually saying any of the guys I name are ‘Englishmen’ in any straightforward sense, but rather that their authoritative, bland, whiteness – accompanied by a precise, recieved English accent – is what is currently dominant when global pop culture conceives of an ‘Englishman’ is. It doesn’t matter if they’re German-Irish and playing an American-Albanian in the movie. Indeed, the very confusion on this point would make an interesting angle from which to further attack the ukippian idea of plausible racial/national ‘accuracy’.

May 23, 2016 @ 2:49 am

Jack Graham (to Michael Fassbender): Well, let me tell you something, my kraut-mick friend, I’m gonna make so much trouble for you, you won’t know what hit you!

May 20, 2016 @ 6:50 am

Now that is how you stick a landing.

May 20, 2016 @ 12:43 pm

Minor point really, but I’m pretty sure Russell Brand wasn’t in ‘Shakespeare Live!’. Tim Minchin was, and I guess he’s kind of similar looking, but then he has red hair and is Australian.

May 20, 2016 @ 6:45 pm

God, this article is Factual Error City.

May 20, 2016 @ 12:57 pm

I don’t know if you’ve caught up on ‘Hollow Crown’ yet but it’s interesting to note that I believe it is only Richard that delivers monologues straight to camera – the rest are played as characters talking to themselves or as voice-over. All methods work for their respective characters I feel.

May 20, 2016 @ 6:46 pm

Now that’s interesting!

May 22, 2016 @ 7:27 am

“who was vastly unpopular for most of her reign, contrary to the Gloriana myth”

Well, no. Elizabeth’s popularity is a complex topic, sure. In fact, measuring the popularity of any early modern European monarch is a bit of a mug’s game. Nonetheless, saying she was “vastly unpopular” for “most of her reign” is just plain wrong.

Her popularity did decline considerably in the final decade of her reign. The Armada victory was glorious enough, but after that the war with Spain didn’t go well; it turned into an endless, brutal slog of attrition and lost battles, with national heroes like Drake and Hawkins going down to humiliation and death. Meanwhile the Irish front was a black hole for men and money — England was winning its war of conquest there, but it was a slow and horrible grind, sucking up countless thousands of English soldiers. And both wars were of course ridiculously expensive, so Liz had to raise taxes and hand out hated Royal monopolies to wealth courtiers. (She’d walk that back after the Golden Speech, but that came only after Parliament was on the brink of mutiny.)

It didn’t help matters that the weather turned bad; there were half a dozen bad harvests in the 1590s, including a couple of no-kidding famine years. And then Liz herself got increasingly cranky and morose as she got older; she could still dazzle and overawe when she wanted to, but mostly she just stopped caring.

ALL THAT SAID, Elizabeth’s relative unpopularity in the 1590s should neither (1) be exaggerated, nor (2) be projected back into the earlier years of her reign, when AFAWCT she actually was pretty popular and well-loved by the standards of then and there. Liz’s government was — by the low standards of then-and-there — reasonably competent, fair, and clean. She ran the country competently, kept the nobility in check, defended successfully against both internal rebellion and external invasion, and managed to split the difference on the religious question. That last was particularly critical; no other contemporary western European country managed this without massive violence, either horrific repression or bloody civil war. Elizabeth’s subjects could look across the channel to France (three civil wars in a generation) or the Netherlands (bloody repression under Alva, followed by eighty years of war) to get some idea of what they were missing.

So Liz was generally pretty popular for most of her reign. Note that over the course of her reign she went on almost forty “progresses” around the country, usually in the Midlands but sometimes as far out as Lancashire or Wales. During these, she regularly traveled without bodyguards and frequently mixed with large groups commoners — if not peasants, at least the local bourgeois. This was in stark contrast to both her predecessor Mary and her successor James.

If you want an example of a contemporary monarch who was actually “vastly unpopular” for most of his reign, you can look right across the channel at Henry III of France. Henry was pretty universally reviled, and his death, at the hands of an assassin, caused outbreaks of wild celebration across the country.

Doug M.