His Name Burning, His Voice Below Things. All Suffering Nourishes That Presence (The Last War in Albion Book Two Part Thirty-Three: Tyger)

Previously in The Last War in Albion: Blake’s artistic career was a continual and unceasing war against the very notion of certainty and fixity, as represented in the figure of Urizen.

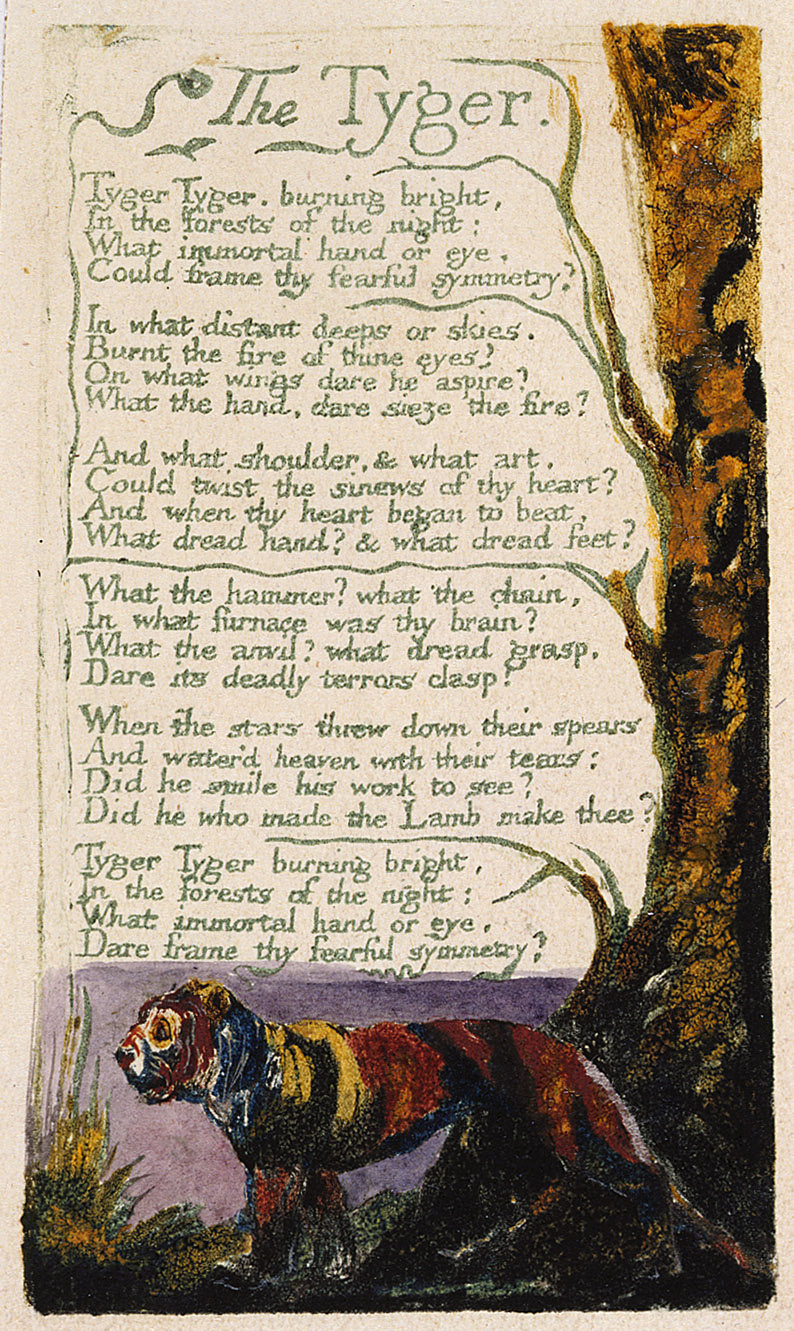

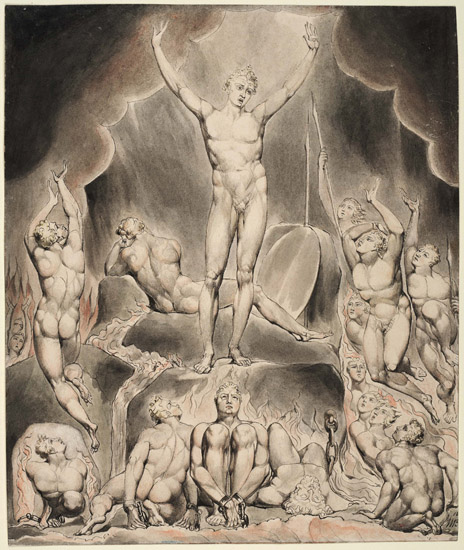

But there is a more foundational aspect of Blake’s unfixed style – one upon which these textual incommensurabilities build. Blake’s illuminated works exist in individually printed and hand-colored copies, no two of which are identical. In the case of The Book of Urizen, for instance, eight copies are known to exist, six of which are widely available. And the differences among these copies are significant; as mentioned, the fourth plate (from which the “solid without fluctuation” line originates) only exists in three of the copies. No two copies place the full-plate illustrations in the same order or locations throughout the text. Plates 8 and 10 each contain the beginning of a section labeled Chapter IV, each of which begins with a stanza numbered 1; on top of that, the order of the two plates is reversed in several copies. Several illustrations change dramatically across copies as well; Plate 6 depicts three figures hung upside-down, bound in serpents, and cast into fire, save for in Copy D, where there is but a single figure. Plate 16, meanwhile, depicts Los in two of the three copies in which it is included, while in a third the figure is given a white beard indicating that it is Urizen. And these are just the variations with the biggest interpretive implications: every page of every copy has its own idiosyncratic decisions of coloring. Nor is this phenomenon unique to The Book of Urizen. Even Blake’s most iconic and nominally fixed poem, “The Tyger,” exists in nearly thirty separate copies, printed and colored over the course of more than thirty years, with major differences across the coloring.

But there is a more foundational aspect of Blake’s unfixed style – one upon which these textual incommensurabilities build. Blake’s illuminated works exist in individually printed and hand-colored copies, no two of which are identical. In the case of The Book of Urizen, for instance, eight copies are known to exist, six of which are widely available. And the differences among these copies are significant; as mentioned, the fourth plate (from which the “solid without fluctuation” line originates) only exists in three of the copies. No two copies place the full-plate illustrations in the same order or locations throughout the text. Plates 8 and 10 each contain the beginning of a section labeled Chapter IV, each of which begins with a stanza numbered 1; on top of that, the order of the two plates is reversed in several copies. Several illustrations change dramatically across copies as well; Plate 6 depicts three figures hung upside-down, bound in serpents, and cast into fire, save for in Copy D, where there is but a single figure. Plate 16, meanwhile, depicts Los in two of the three copies in which it is included, while in a third the figure is given a white beard indicating that it is Urizen. And these are just the variations with the biggest interpretive implications: every page of every copy has its own idiosyncratic decisions of coloring. Nor is this phenomenon unique to The Book of Urizen. Even Blake’s most iconic and nominally fixed poem, “The Tyger,” exists in nearly thirty separate copies, printed and colored over the course of more than thirty years, with major differences across the coloring.

|

| Figure 962: One of the few versions of “The Tyger” in which the beast actually seems to burn bright in a forest of the night. (By William Blake, from Songs of Innocence and Experience Copy T, written 1794, printed 1818) |

“The Tyger” is a fitting thing to look at here, not least because it shares some of the particular horror of The Book of Urizen with its deadly terrors, dread grasp, and, perhaps most obviously, its fearful symmetry, a phrase that seems tailor made for the geometric precision of Urizen. But more than that, “The Tyger” illustrates another means by which Blake destabilizes his texts, namely the gap that opens up between image and text. For all the anthology-friendly bombast of the poem, after all, it is impossible to escape the fact that in the overwhelming majority of the copies, the image is not that of a monstrously incandescent Tyger, but of an ordinary, at times even downright goofy looking tiger. This is not universally true – in particular, Copies T and F adopt a strikingly dark color palate, such that the flashes of yellow and orange really do seem to burn brightly out of some limitlessly dark woods.…

With Shabcast 18 vanished into the ether, this week we move straight on to Shabcast 19. My now-frequent-interlocutor Daniel Harper of

With Shabcast 18 vanished into the ether, this week we move straight on to Shabcast 19. My now-frequent-interlocutor Daniel Harper of

The Kickstarter for Neoreaction a Basilisk will begin next week. For now, here’s another excerpt, this time after a section looking at the notion of “the red pill,” a concept Mencius Moldbug introduced to the alt-right, and claims that his blog offers readers.

The Kickstarter for Neoreaction a Basilisk will begin next week. For now, here’s another excerpt, this time after a section looking at the notion of “the red pill,” a concept Mencius Moldbug introduced to the alt-right, and claims that his blog offers readers. This wasn’t on the original list of games to be covered. Consider its inclusion something of a magickal mistake, honored as hidden intention. I cast my initial circle carelessly, and, through an accident of timing, ensconced a particular monster within the territory covered. This, then, is the consequence.

This wasn’t on the original list of games to be covered. Consider its inclusion something of a magickal mistake, honored as hidden intention. I cast my initial circle carelessly, and, through an accident of timing, ensconced a particular monster within the territory covered. This, then, is the consequence.