Chapter Ten: Where The Moon and the Earth Were Joined (Two Riders Were Approaching)

In order to understand Moore’s transformation it is necessary to fully understand precisely what Watchmen was and what it did. And to understand this it is necessary to appreciate one of its major thematic concerns, the prospect of nuclear annihilation. This aspect of the War entered the scene approximately one picosecond after the creation of the universe, when the electroweak force, unable to cohere once the universe cooled below 1015 K, split into the electromagnetic force, which would go on to underpin more or less the entirety of communication, and the weak nuclear force. This latter force was responsible for a phenomenon called beta decay, in which a neutron can transform itself into a proton by expelling an electron, along with other forms of radioactive decay. Together, along with gravity and the strong nuclear force, they create a delicate mathematical balance in which matter and life are possible. And yet within that crucial weak force is a terrifying implication.

In order to understand Moore’s transformation it is necessary to fully understand precisely what Watchmen was and what it did. And to understand this it is necessary to appreciate one of its major thematic concerns, the prospect of nuclear annihilation. This aspect of the War entered the scene approximately one picosecond after the creation of the universe, when the electroweak force, unable to cohere once the universe cooled below 1015 K, split into the electromagnetic force, which would go on to underpin more or less the entirety of communication, and the weak nuclear force. This latter force was responsible for a phenomenon called beta decay, in which a neutron can transform itself into a proton by expelling an electron, along with other forms of radioactive decay. Together, along with gravity and the strong nuclear force, they create a delicate mathematical balance in which matter and life are possible. And yet within that crucial weak force is a terrifying implication.

This implication (and indeed the weak force itself) went unnoticed for approximately fourteen billion years, until German chemists Otto Hahn and Fritz Strassman first achieved nuclear fission in 1938. Their work, of course, was simply a momentary endpoint of a larger chain of thought—the revolutions of theoretical physics that swept the scientific community in the early 20th century, upending the classical notions of the world and how it worked. Einstein, Bohr, Heisenberg, and the rest, in a series of dizzying discoveries over the course of decades, unseated the idea of a fixed and knowable universe, finding instead a universe that is fundamentally ordered by human perception, where the act of looking shapes the thing being observed—a quantum revolution that brought, in its wake, the possibility of magic. And then, with Hahn and Strassman, a very different possibility.

Hahn and Strassman conducted an experiment in which they bombarded uranium with neutrons. Observing the result, they discovered to their astonishment that the process had created atoms of barium. Reading a letter about these results, their former colleague Lisse Meitner, a Jewish chemist who had fled Germany earlier in the year, she reasoned that if Niels Bohr’s theory of the atomic nucleus, which held that it worked more or less like a drop of liquid, were correct then a very large nucleus like uranium would be unstable—indeed, unstable enough that the weak force impact of a neutron could lead the nucleus to stretch and eventually snap like a cell dividing into two. Running the calculations further, Meitner realized that the result would have less mass than the original atom, and that the lost mass must be converted into energy—indeed, a tremendous amount of energy, at least for a single atomic reaction, although on its own it was barely enough to move a speck of dust.

Word of the discovery spread quickly, and in early 1939 Niels Bohr brought word across the Atlantic as he traveled to lecture at Princeton. This set off a wave of experimentation and theorization, in which several scientists including Leó Szilárd, Enrico Fermi, and Frédéric Joliot-Curie all came to the same realization: the reaction released more than one neutron.…

And what of Moore? Where was he as the company he forsook remade itself in what they imagined his image to be? How did the Prophet of Eternity respond to what he had wrought?

And what of Moore? Where was he as the company he forsook remade itself in what they imagined his image to be? How did the Prophet of Eternity respond to what he had wrought?

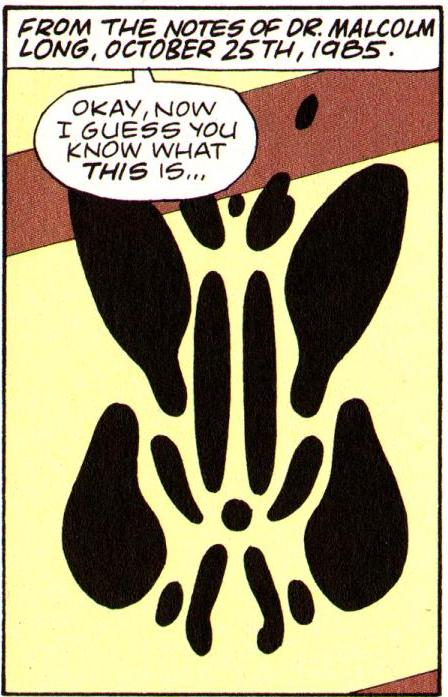

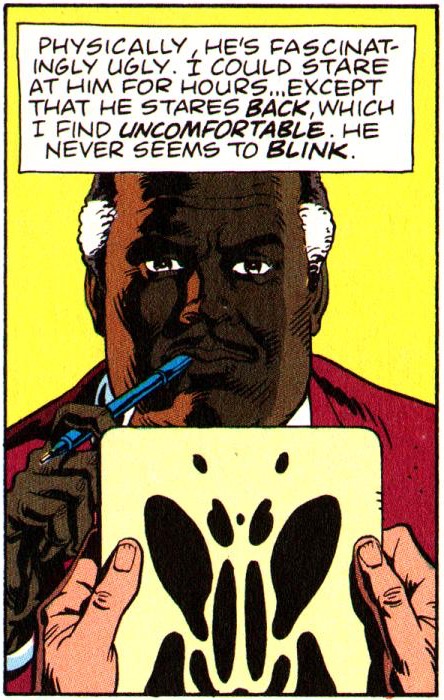

The core of the problem was that from DC’s perspective, the lesson of Watchmen could only ever be one thing: things like this sold. And within the post-Crisis reality of the direct market, what DC specifically cared about was what fans said. The simple reality is that what the vocal fans who showed up and bought Watchmen in their specialist comic book stores liked most about the book wasn’t the moving explorations of sexuality in “A Brother To Dragons”; it was Rorschach being a moody badass in “The Abyss Gazes Also.” And so this is what DC imitated.

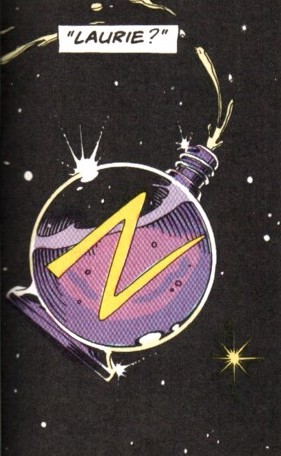

The core of the problem was that from DC’s perspective, the lesson of Watchmen could only ever be one thing: things like this sold. And within the post-Crisis reality of the direct market, what DC specifically cared about was what fans said. The simple reality is that what the vocal fans who showed up and bought Watchmen in their specialist comic book stores liked most about the book wasn’t the moving explorations of sexuality in “A Brother To Dragons”; it was Rorschach being a moody badass in “The Abyss Gazes Also.” And so this is what DC imitated. Consider January of 1987, the month that Moore finally came to the decision that he would not accept any new work from DC. In addition to Watchmen #8, in which Rorschach breaks out of prison with the help of Dan and Laurie after violently murdering his way through a number of inmates, high profile comics being released included the final issue of Legends, DC’s first attempt to duplicate the success of Crisis on Infinite Earths, two issues of John Byrne’s Superman run, and an issue of George Pérez’s Wonder Woman. In more grim and gritty terms, DC released an issue of Vigilante, with its right-wing fantasy of extrajudicial executions, and The Question, which saw Denny O’Neil putting his own spin on Rorschach’s source material, and the third installment of Frank Miller’s post-Crisis Batman: Year One relaunch. But even within the Batman line, that same month saw the release of Detective Comics #573, a goofball issue featuring the Mad Hatter, albeit one that ends with Robin being shot and gravely wounded. But DC still had at least one eye firmly situated on the past. Other titles included Infinity Inc., co-written by Roy Thomas, a twenty-year veteran of the industry who had succeeded Stan Lee as editor in chief at Marvel Comics.…

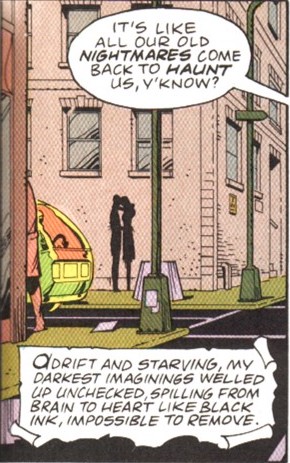

Consider January of 1987, the month that Moore finally came to the decision that he would not accept any new work from DC. In addition to Watchmen #8, in which Rorschach breaks out of prison with the help of Dan and Laurie after violently murdering his way through a number of inmates, high profile comics being released included the final issue of Legends, DC’s first attempt to duplicate the success of Crisis on Infinite Earths, two issues of John Byrne’s Superman run, and an issue of George Pérez’s Wonder Woman. In more grim and gritty terms, DC released an issue of Vigilante, with its right-wing fantasy of extrajudicial executions, and The Question, which saw Denny O’Neil putting his own spin on Rorschach’s source material, and the third installment of Frank Miller’s post-Crisis Batman: Year One relaunch. But even within the Batman line, that same month saw the release of Detective Comics #573, a goofball issue featuring the Mad Hatter, albeit one that ends with Robin being shot and gravely wounded. But DC still had at least one eye firmly situated on the past. Other titles included Infinity Inc., co-written by Roy Thomas, a twenty-year veteran of the industry who had succeeded Stan Lee as editor in chief at Marvel Comics.… There is, however, another important sense in which Rorschach represents a myopia within Watchmen and, more broadly, Moore’s larger artistic vision. As mentioned, a crucial part of Rorschach’s psychology is his tortured relationship with sexuality. Sex is a major theme of both Watchmen and Moore’s career, and one that he has much of value to say about, but there is something unseemly about the directness with which Rorschach’s disgust with sex is pathologized, not least because it’s a character trait inherited from his underlying relationship with the apparently asexual Steve Ditko. More broadly, there is something oversimplified and unsatisfying in Moore’s approach to sexuality—a flaw intimately connected to his persistent inadequacy on the subject of sexual assault. This would be a relatively minor issue were it not for the awkward fact that the relationship between superheroes and sexuality is one of the comic’s major themes.

There is, however, another important sense in which Rorschach represents a myopia within Watchmen and, more broadly, Moore’s larger artistic vision. As mentioned, a crucial part of Rorschach’s psychology is his tortured relationship with sexuality. Sex is a major theme of both Watchmen and Moore’s career, and one that he has much of value to say about, but there is something unseemly about the directness with which Rorschach’s disgust with sex is pathologized, not least because it’s a character trait inherited from his underlying relationship with the apparently asexual Steve Ditko. More broadly, there is something oversimplified and unsatisfying in Moore’s approach to sexuality—a flaw intimately connected to his persistent inadequacy on the subject of sexual assault. This would be a relatively minor issue were it not for the awkward fact that the relationship between superheroes and sexuality is one of the comic’s major themes. The theme of sex within Watchmen ignites in the seventh issue, “A Brother to Dragons,” which forms, along with “The Abyss Gazes Also,” a symmetrical axis at the center of the series. Watchmen can be divided into two types of issues: ensemble pieces that feature a large cross-section of the cast, and character-focused issues that provide backgrounds and meditations on individual heroes. The first half of the book alternates between these two types, with “At Midnight, All the Agents,” “The Judge of All the Earth,” and “Fearful Symmetry” jumping among multiple points of view while “Absent Friends,” “Watchmaker,” and “The Abyss Gazes Also” focus on the Comedian, Dr. Manhattan, and Rorschach respectively. The second half also alternates back and forth, but here it is the odd-numbered issues that are character-focused, looking at Ozymandias, Silk Spectre, and, in “A Brother To Dragons,” Night Owl.

The theme of sex within Watchmen ignites in the seventh issue, “A Brother to Dragons,” which forms, along with “The Abyss Gazes Also,” a symmetrical axis at the center of the series. Watchmen can be divided into two types of issues: ensemble pieces that feature a large cross-section of the cast, and character-focused issues that provide backgrounds and meditations on individual heroes. The first half of the book alternates between these two types, with “At Midnight, All the Agents,” “The Judge of All the Earth,” and “Fearful Symmetry” jumping among multiple points of view while “Absent Friends,” “Watchmaker,” and “The Abyss Gazes Also” focus on the Comedian, Dr. Manhattan, and Rorschach respectively. The second half also alternates back and forth, but here it is the odd-numbered issues that are character-focused, looking at Ozymandias, Silk Spectre, and, in “A Brother To Dragons,” Night Owl. The line, of course, belongs to Rorschach, the glamorous poison at the heart of Watchmen’s appeal. Moore is self-effacing about the character these days, joking that his popularity is down to the fact that Moore “had forgotten that actually to a lot of comic fans that smelling, not having a girlfriend – these are actually kind of heroic.” But unlike a lot of Moore’s self-deprecation, there’s an edge to this quip. He’s emphasizing his failure to anticipate the reaction to Rorschach, but only as a means to insult Rorschach’s fans even more spectacularly. There are obviously a lot of things about Watchmen that have gone sour for Moore, but at times it seems that there is nothing he resents quite as deeply as the reception of Rorschach.

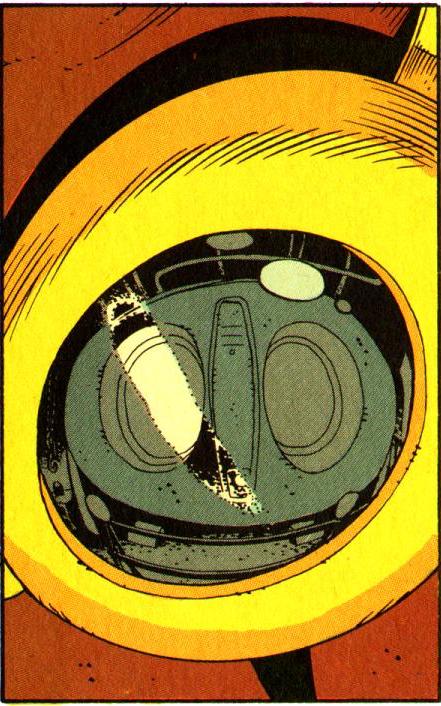

The line, of course, belongs to Rorschach, the glamorous poison at the heart of Watchmen’s appeal. Moore is self-effacing about the character these days, joking that his popularity is down to the fact that Moore “had forgotten that actually to a lot of comic fans that smelling, not having a girlfriend – these are actually kind of heroic.” But unlike a lot of Moore’s self-deprecation, there’s an edge to this quip. He’s emphasizing his failure to anticipate the reaction to Rorschach, but only as a means to insult Rorschach’s fans even more spectacularly. There are obviously a lot of things about Watchmen that have gone sour for Moore, but at times it seems that there is nothing he resents quite as deeply as the reception of Rorschach. The fundamental problem at the heart of this is simply that Rorschach is an unsettlingly fascinating character. Even Moore, for all the reservations he would come to have about him, freely admits that “Rorschach was one of the characters I enjoyed writing most.” And no wonder – think of a classic line in Watchmen and the odds are overwhelming that you’re thinking of a Rorschach line, probably either a bit of his opening monologue or “none of you understand. I’m not locked up in here with you. You’re locked up in here with me.” Whether or not one relates to the character, he is undeniably compelling, reliably giving the book a jolt of energy whenever he shows up.

The fundamental problem at the heart of this is simply that Rorschach is an unsettlingly fascinating character. Even Moore, for all the reservations he would come to have about him, freely admits that “Rorschach was one of the characters I enjoyed writing most.” And no wonder – think of a classic line in Watchmen and the odds are overwhelming that you’re thinking of a Rorschach line, probably either a bit of his opening monologue or “none of you understand. I’m not locked up in here with you. You’re locked up in here with me.” Whether or not one relates to the character, he is undeniably compelling, reliably giving the book a jolt of energy whenever he shows up.