The Proverbs of Hell 35/39: And The Woman Clothed With The Sun

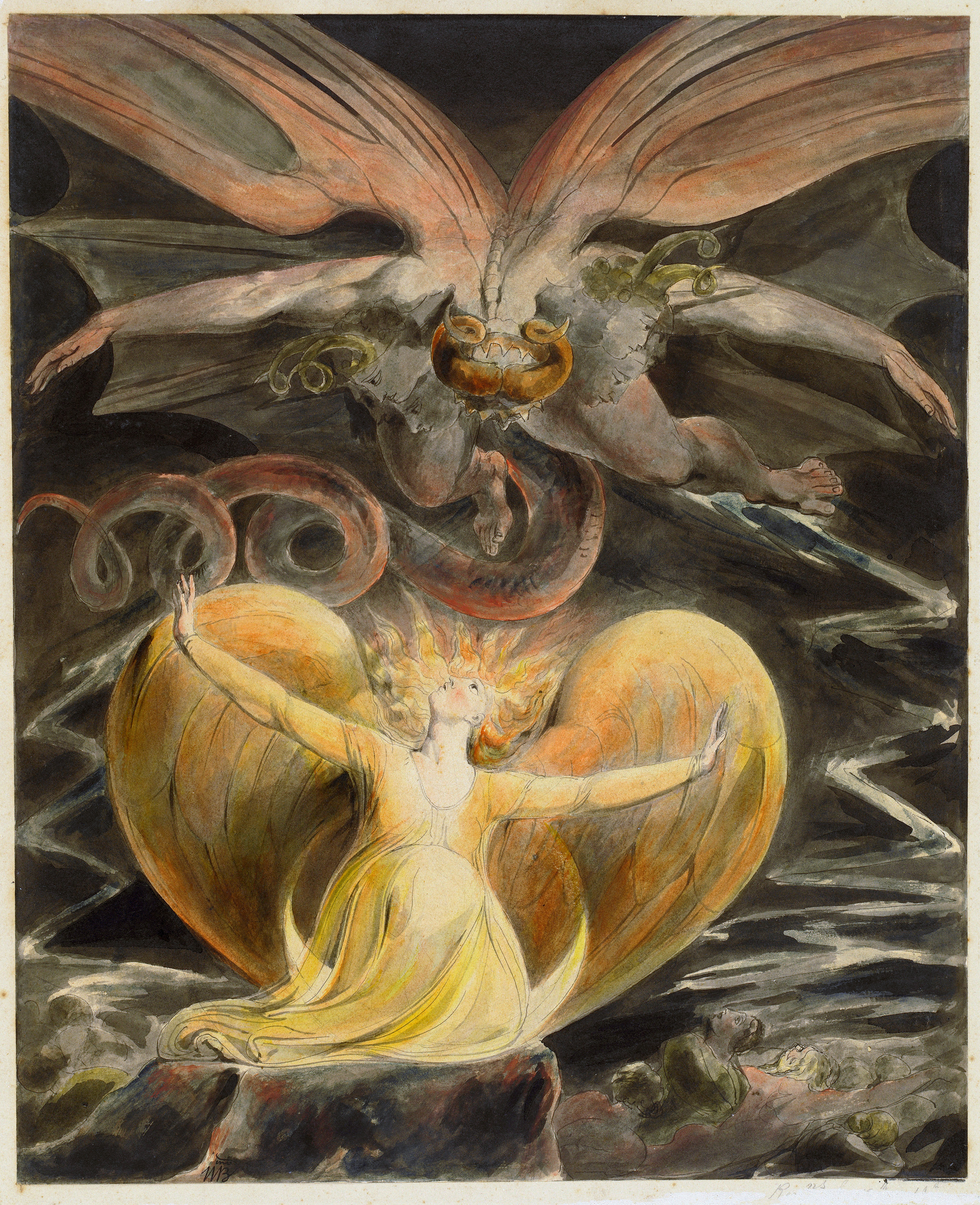

AND THE WOMAN CLOTHED WITH THE SUN: This is not the picture that Dolarhyde worships, which is “The Great Red Dragon and the Woman Clothed in Sun.” The distinction flummoxed Harris himself, who got the wrong one in Red Dragon, and the most satisfying explanation for this preceding the episode named after the story’s central painting is that Fuller is providing an homage to the error. In any case, this painting is essentially Dolarhyde’s from the opposite perspective. The result is that the woman is the central object of the painting, with the Dragon looming above her, mimicking our own act of looking at her. The picture Dolarhyde prefers is on the whole the far more interesting framing, which we’ll get to next week.

AND THE WOMAN CLOTHED WITH THE SUN: This is not the picture that Dolarhyde worships, which is “The Great Red Dragon and the Woman Clothed in Sun.” The distinction flummoxed Harris himself, who got the wrong one in Red Dragon, and the most satisfying explanation for this preceding the episode named after the story’s central painting is that Fuller is providing an homage to the error. In any case, this painting is essentially Dolarhyde’s from the opposite perspective. The result is that the woman is the central object of the painting, with the Dragon looming above her, mimicking our own act of looking at her. The picture Dolarhyde prefers is on the whole the far more interesting framing, which we’ll get to next week.

HANNIBAL: That’s the same atrocious aftershave you wore in court.

WILL GRAHAM: Hello, Dr. Lecter.

HANNIBAL: Hello, Will. Did you get my note?

WILL GRAHAM: I got it. Thank you.

HANNIBAL: Did you read it before you destroyed it? Or did you simply toss it into the nearest fire?

WILL GRAHAM: I read it. And then I burned it.

HANNIBAL: And you came anyway. I’m glad you came. My other callers are all professional. Banal psychiatrists and grasping second-raters. Pencil-lickers trying to protect their tenure with pieces in the journals.

WILL GRAHAM: I want you to help me, Dr. Lecter.

HANNIBAL: Yes, I thought so. Are we no longer on a first-name basis?

WILL GRAHAM: I’m more comfortable the less personal we are.

HANNIBAL: Your hands are rough. I smell dogs and pine and oil beneath that shaving lotion. It’s something a child would select, isn’t it? There a child in your life, Will?

WILL GRAHAM: I’m here about Chicago and Buffalo. You’ve read about it, I’m sure.

HANNIBAL: I’ve read the papers. I can’t clip them. They won’t let me have scissors, of course. You want to know how he’s choosing them.

WILL GRAHAM: Thought you would have some ideas.

HANNIBAL: You just came here to look at me. Came to get the old scent again. Why don’t you just smell yourself?

We may as well just do the entire exchange here. The sections in boldface are original to the show. The remainder is more or less from the book, with a few small adjustments. (It’s a card in the book, the “dogs and pine oil” is new, and the murders have been moved north from their original Atlanta and Birmingham locations.) This exchange, of course, is the most iconic in Red Dragon, and for obvious reason. Fuller to do anything other than let Mikkelsen and Dancy at it would have been criminal. Matthew Morettini has done a supercut of the three adaptations that’s interesting a much in its disjuncts as its unities. Within the context of Hannibal, however, what jumps out most aggressively is the degree to which the scene is stilted. Fuller’s version of these characters has become so much more than what is in Harris’s book, and while Mikkelsen and Dancy acquit themselves well upon the lines, it still feels momentarily odd to see them in this more stripped down iteration.…

$5000 in Two Days. Dang. (Also two new reward tiers)

After what was not only the best launch day i’ve ever had for a Kickstarter but the best second day I’ve ever had as well, the TARDIS Eruditorum Volume 7 Kickstarter has managed to break $5000 in just two days. I am stunned, humble, and unbelievably grateful. That’s not only enough to print the book, but enough to get bonus essays on Nightshade, Springhill (a mostly overlooked and forgott4en Russell T Davies supernatural soap opera worked on by Gareth Roberts, Paul Cornell, and Frank Cottrell-Boyce), and “Was He Half-Woven On His Father’s Side?”, my essay on Looms and whether they make any goddamn sense. The next couple stretch goals are on the Andrew Cartmel-overseen season of Casualty (I got my hands on it!), the Big Finish audio Master, and Lloyd Rose’s novel The Algebra of Ice. Plus we’re halfway to the Kate Orman interview!

Anyway, by popular request I’ve added two new reward tiers for people who want to catch up on the Eruditorum Press catalog, but don’t necessarily want all seven TARDIS Eruditorum Books. There’s a $10 ebook threepack, and a $60 print threepack. Either can include Volume 7 if you like, but can also include Volumes 1-6, The Last War in Albion, A Golden Thread, Guided by the Beauty of Their Weapons, or Neoreaction a Basilisk. (And the print one can include Recursive Occlusion too if you like.) These can be added to existing pledges, so if you’d like them but have already backed at another tier I am happy to separate you from more of your money. As the Daleks say in “Doctorin’ the TARDIS,” “DOSH DOSH DOSH LOADSAMONEY!”

Once again, the Kickstarter’s here. Thanks again. …

Salamancans and Austrians

In his researches into Hayek’s role in the decision to hold the 1981 conference of the Mont Pèlerin Society (MPS) in Pinochet’s Chile, Corey Robin discovered a 1979 letter from Hayek to another MPS member in which he enthusiastically – and, as it transpires, successfully – endorsed Madrid as a conference venue.

In his researches into Hayek’s role in the decision to hold the 1981 conference of the Mont Pèlerin Society (MPS) in Pinochet’s Chile, Corey Robin discovered a 1979 letter from Hayek to another MPS member in which he enthusiastically – and, as it transpires, successfully – endorsed Madrid as a conference venue.

For several years, Hayek had been growing increasingly excited about the possibility that “the basic principles of the theory of the competitive market were worked out by the Spanish scholastics of the 16th century.” For reasons still obscure to me, he seemed positively ecstatic about the notion that “economic liberalism was not designed by the Calvinists but by the Spanish jesuits.” (In his History of Economic Analysis, Schumpeter also had argued “that the very high level of Spanish sixteenth-century economics was due chiefly to the scholastic contributions.” But it didn’t seem to transport him in the way it did Hayek.)

Hayek insisted that the conference be shipped for a day 132 miles northwest of Madrid in order “to celebrate at Salamanca”—the university town where this specific branch of early modern natural law theory was formulated—”the Spanish origins of liberal economics.”

He got his way: the MPS members dutifully got into their buses and, like medieval penitents following their shepherd, made their pilgrimage to the birthplace of free-market economics

[My emphasis.]

As Robin notes, Schumpeter was also excited by this idea – as was Rothbard. Schumpeter called the Late Scholastics “the first economists”. Rothbard’s contention was that the Salamancans were yet more of the precursors to the Austrian School that he liked to find everywhere. Even today, Austrians are into the idea of the Salamancans being their precursors.

More generally, libertarians have a bit of a fetish for it. Alejandro Chafeun, one-time Randian, member of the Mont Pelerin Society, and president of the Atlas Foundation (a free-market think tank in case you couldn’t guess), wrote a book on the subject called Faith and Liberty which Mises dot org thinks highly of. I haven’t read Chafeun’s book, so I can’t comment on his conclusions, but I will say that I find the idea of modern economics being prefigured – to an extent – in the writings of Late Renaissance Catholic scholars perfectly plausible. Modern economics is an expression of capitalism and capitalism grew in the womb of Early Modern Europe, of which the Catholic Church was still the main ideological producer for a long time. Catholicism came to express nascent capitalism in its own way, much as did many pre-existing aspects of feudal Europe, even if Reformation ideas were also an expression of the rise of the new system. The ways in which power structures and ideologies respond to underlying economic changes are complex and non-schematic. Lutheranism arose partly from indignation at the sale of indulgences by the Church, itself an expression of the rising marketisation of feudal society.

It’s worth taking a moment here. As far as I’m aware, the most concise expression of the best version of the Marxist view of the relation between the Reformation and the rise of capitalism was written by Chris Harman in his A People’s History of the World:

…Historians have wasted enormous amounts of time arguing over the exact interrelation between capitalism and Protestantism.

TARDIS Eruditorum Volume 7 Kickstarter

Eruditorum Press is pleased to announce the launch of our latest Kickstarter, for TARDIS Eruditorum Volume 7: Sylvester McCoy. You can check it out here. The goal is a modest $2000 which, given that it’s made it to $165 in the time it took me to log into the site and start this post, I expect we’re going to make, but there’s stretch goals every $1000 after that all the way up to $14,000, which will add up to thirteen bonus essays if we can make it through them all. The crown jewel is probably at $10,000, where I’ll do an interview on the Sylvester McCoy era with the legendary Kate Orman, but there’s good stuff throughout, from covering Mark Gatiss’s Doctor Who debut Nightshade all the way up to finally writing about The Pit. (And no, that’s not the actual cover; it’s just what James had time to design this month. Though I do kinda love it.)

Eruditorum Press is pleased to announce the launch of our latest Kickstarter, for TARDIS Eruditorum Volume 7: Sylvester McCoy. You can check it out here. The goal is a modest $2000 which, given that it’s made it to $165 in the time it took me to log into the site and start this post, I expect we’re going to make, but there’s stretch goals every $1000 after that all the way up to $14,000, which will add up to thirteen bonus essays if we can make it through them all. The crown jewel is probably at $10,000, where I’ll do an interview on the Sylvester McCoy era with the legendary Kate Orman, but there’s good stuff throughout, from covering Mark Gatiss’s Doctor Who debut Nightshade all the way up to finally writing about The Pit. (And no, that’s not the actual cover; it’s just what James had time to design this month. Though I do kinda love it.)

You may be wondering why I’m doing a Kickstarter for Volume 7 given that I didn’t for the initial releases of any previous TARDIS Eruditorum. Two basic reasons. 1) Books I sell directly via Kickstarter net me a far higher royalty than books sold through Amazon, and so I’m moving to a Kickstarter-based model for all future releases. 2) I’m kinda broke. It’s nothing crushing and unmanageable; I’ve got a month-to-month income that’s roughly commensurate with expenses. But my saving account is currently at “ha ha ha no,” and that’s kinda stressful. Hence Kickstarter.

But that’s depressing, so let’s talk about cool stuff. Like the Kickstarter-exclusive hardcover edition that will be signed, numbered, and never for sale ever again after February 28th. Or the opportunity to catch up on the entire TARDIS Eruditorum series in print or digital at a nice and healthy discount. Or, if you really don’t have much but still want to support, at just $1 you can read a preview of the TARDIS Eruditorum entry for Deep Breath. (Which, btw, the Patreon is just $19 away from the full compliment of Capaldi-era Pop Between Realities, Outside the Government, and You Were Expecting Someone Else essays if you want to back that too.)

Whatever you can give is extremely welcome. And if the money isn’t going to work out for you to donate this month, you can at least spread the link far and wide. Word of mouth is effective marketing. Twenty seconds on Twitter or Facebook makes a real difference to me.

I’ll be noisy throughout the month with Kickstarter promotion, including, in the very near future, the running order for the Capaldi era. Thanks for your support, and for reading. And one more time, here’s the Kickstarter link.…

The Proverbs of Hell 34/39: The Great Red Dragon

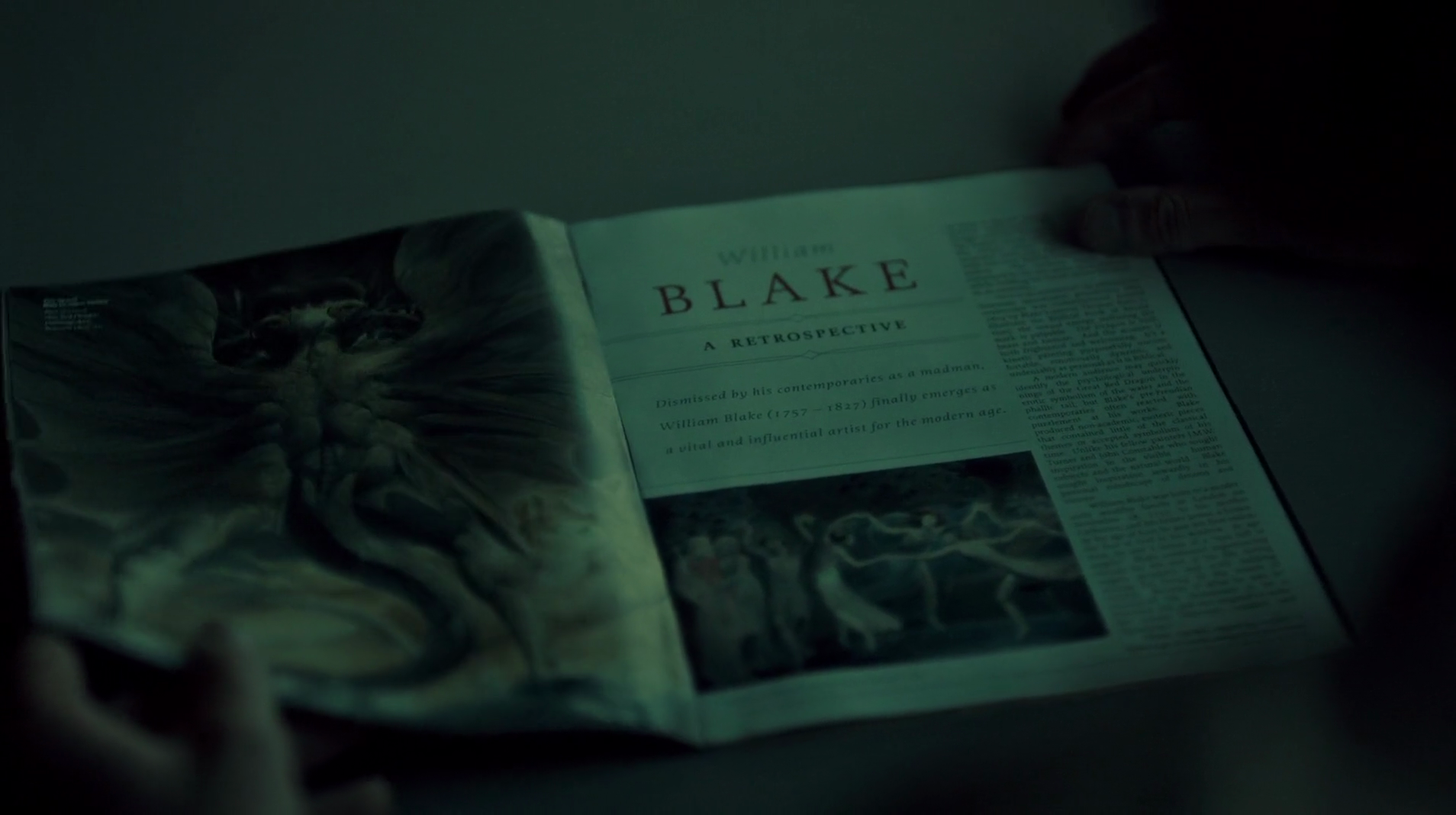

THE GREAT RED DRAGON: After thirty-three episodes named after food, we change gears abruptly to episodes named after works of art by William Blake. This episode does not designate a specific work but rather a series of four paintings in a larger series of water colors illustrating the Bible completed between 1800 and 1806 four of which have titles beginning “The Great Red Dragon.” Thankfully we still have food to illustrate this episode as part of the delightfully barmy decision to let Hannibal still cook in prison, and we can get on to the Blake works starting next episode.

THE GREAT RED DRAGON: After thirty-three episodes named after food, we change gears abruptly to episodes named after works of art by William Blake. This episode does not designate a specific work but rather a series of four paintings in a larger series of water colors illustrating the Bible completed between 1800 and 1806 four of which have titles beginning “The Great Red Dragon.” Thankfully we still have food to illustrate this episode as part of the delightfully barmy decision to let Hannibal still cook in prison, and we can get on to the Blake works starting next episode.

Although Time has on a few occasions in its history had articles on Blake exhibitions, he is not generally considered cover material, and if he were it seems unlikely The Great Red Dragon and the Woman Clothed with the Sun would be the image gone for. But for all its mild silliness, there’s a certain logic to having Dolarhyde encounter the Great Red Dragon in a print magazine, given that Dolarhyde exists in a constant tension with modernity, as we’ll get to.

The first thing to be emphasized about Dolarhyde is his intense physicality—he is, as they say, a beast. This is something of a novelty in Hannibal—there’ve been a handful of killers whose physicality has mattered in some sense (Randall Tier and Georgia Madden spring to mind), but none where the basic threat and danger of them is so rooted in raw puissance.

Finally the influence runs in the opposite direction as Hannibal shamelessly rips off Sherlock.

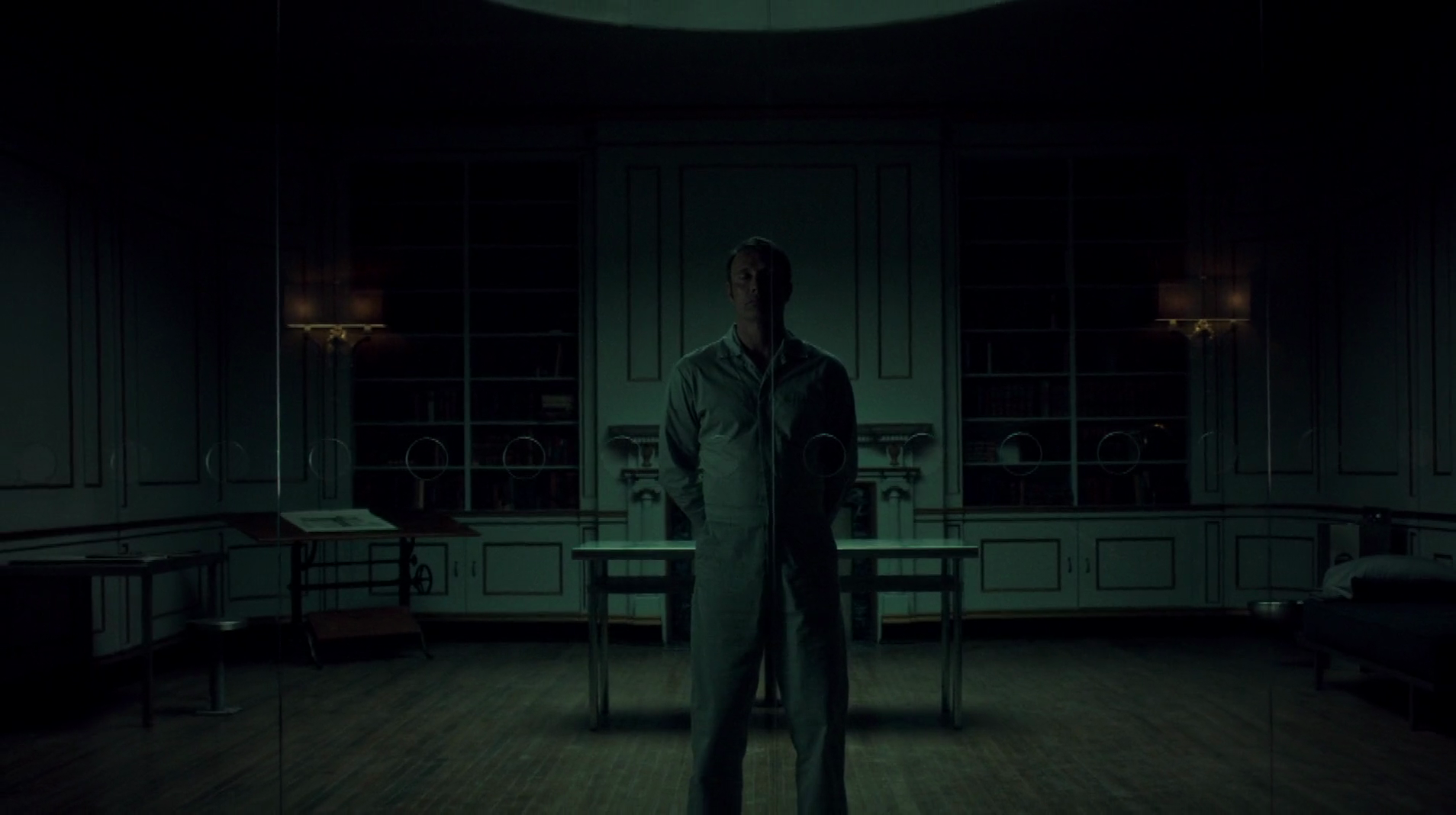

One step away from the outright defining image of Hannibal. It is notable, compared to other depictions of Hannibal in a cell, for its relative lushness—Hannibal’s cell is large and decorated with an ornateness that contrasts utterly with the Baltimore State Hospital for the Criminally Insane as depicted in Seasons One and Two, and he’s afforded a myriad of luxuries unlike the sparse hells usually associated with his incarceration. There are a number of reasons for the change. First, Hannibal here is a character we’ve spent thirty-three episodes with already, and does not need to be a beast at the heart of a terrible dungeon in order to be scary. Second, and somewhat contradictorily, Hannibal here is not monstrous in the same way as in previous versions. Hannibal has made much more peace with the inherent tension of revulsion and adoration the monster in a horror movie elicits. A grand room from which Hannibal grants audiences to lesser creatures is fully in line with what this version of the character is.

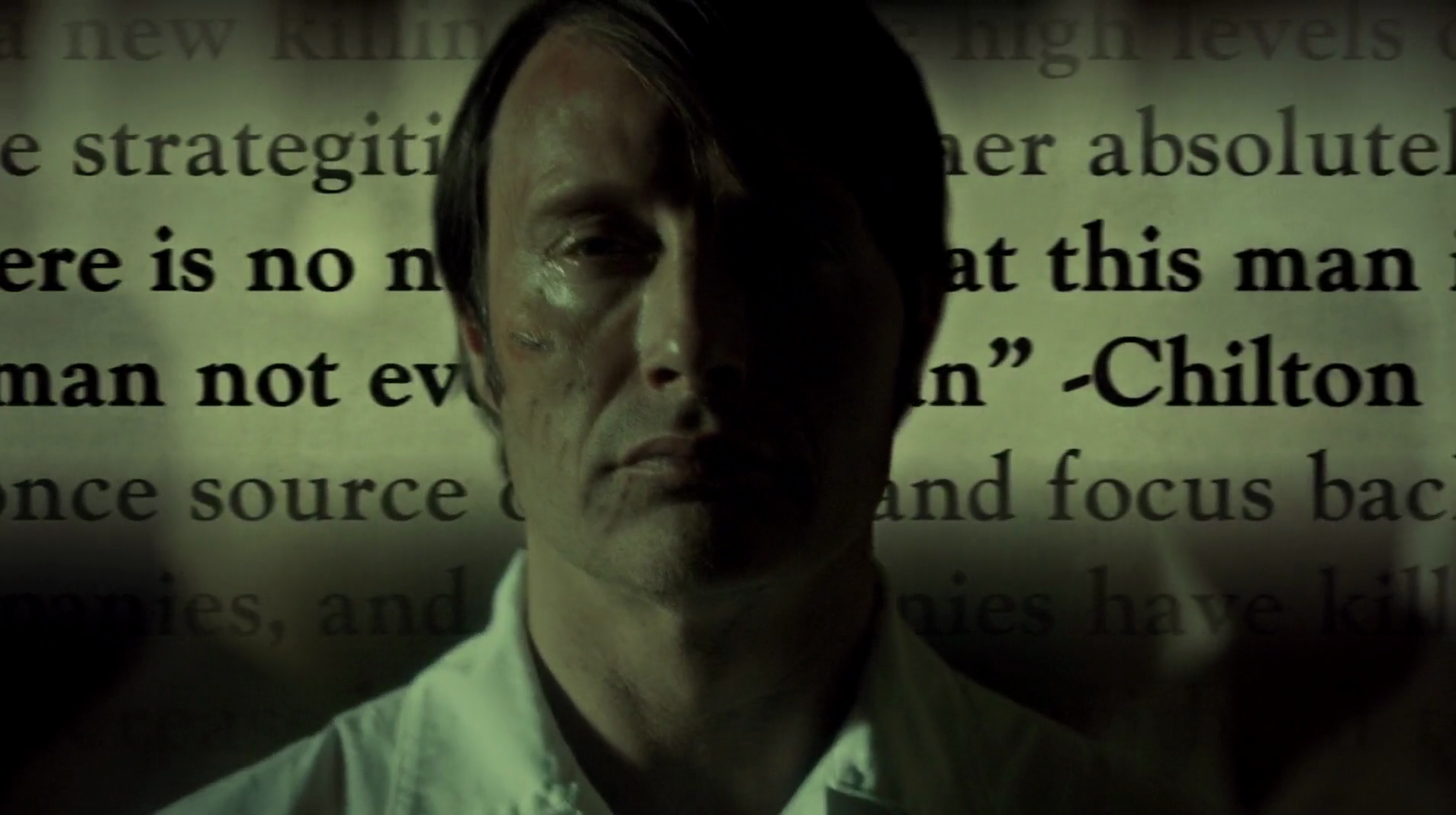

ALANA BLOOM: Congratulations, Hannibal. You’re officially insane.

HANNIBAL: There’s no consensus in the psychiatric community what I should be termed.

ALANA BLOOM: You’ve long been regarded by your peers in psychiatry as something entirely Other. For convenience, they term you a monster.

HANNIBAL: What do you term me?

ALANA BLOOM: I don’t. You defy categorization.

The previous episode asked whether Alana could ever have understood Hannibal. Certainly her attempted distinction between defiance of categorization and monstrosity points towards “no,” although the fault is just as plausibly Fuller and Lightfoot’s.…

Saturday Waffling (January 27th, 2018)

Morning all. The Kickstarter for TARDIS Eruditorum Volume 7: Sylvester McCoy will, unless something goes weirdly wrong, start on Thursday. I’m finalizing the list of stretch goals, which will be the added essays for the bolume, and I wanted to solicit input on McCoy-era stuff I’ve not covered that you’re hoping for in the book version. It can be Virgin or BBC Books novels, Big Finish stories, other media, Pop Between Realities stuff, or larger questions you’d like me to wrestle with.

Nightshade is already on the list, and will be the lowest stretch goal, so you’re almost certain to get that. The final stretch goal will be “force Phil to read The Pit.” There are others I’m pretty sure to have on there, but I’ll leave it vague for now and let you suggest what you will.

Also, due to the existing number of McCoy entries and the fact that there’s some definite chaff in there (both Pop Between Realities stuff that only exists because I couldn’t keep a pace of three novels a week and novels that just didn’t work out as essays), there’s a very high chance some blog material will not make the book. If you have any beloved entries from the McCoy era that you’d be gutted to see fail to make the book, now’s a good time to tell me that.…

Trot On, Hayek!

Another little detour, away from both the recent starwarsing (which will be continued) and from the main line of all this Austriana. Once again, this is a long version of a section of the essay ‘No Law for the Lions and Many Laws for the Oxen is Liberty’, co-written by myself and Phil for his new book Neoreaction a Basilisk, which you – yes you! – can purchase for non-gold backed fiat currency. Buy a copy today – it’s the only rational calculation!

Another little detour, away from both the recent starwarsing (which will be continued) and from the main line of all this Austriana. Once again, this is a long version of a section of the essay ‘No Law for the Lions and Many Laws for the Oxen is Liberty’, co-written by myself and Phil for his new book Neoreaction a Basilisk, which you – yes you! – can purchase for non-gold backed fiat currency. Buy a copy today – it’s the only rational calculation!

Ludwig von Mises – founder of the shittest cult of personality since selfhood itself was invented – famously declared, in an article published in 1920 which was subsequently developed into a book-style object, that socialism – by which he meant any society in which the means of production were commonly owned – was impossible, unworkable. The timing of publication was undoubtedly tied to the fact that, in 1920, it looked to most observers as if the infant Soviet Union was about to expire a mere three years or so after its birth. Mises was positioning himself, with gleeful anticipation, to be able to dance on the grave of the world’s first workers’ state, shouting “told you so!” Unfortunately for Mises, and for a lot of fascists, Trotsky existed.

Mises asserts that public ownership, because it abolishes the capital goods market, means that there can be no determination of prices for capital goods, and therefore no way to determine the relative values of primary resources, and therefore no way to allocate them efficiently and rationally. This claim is patently outrageous coming from people who are putting it forth as a way of championing capitalism, a system that has brought us to the point where the richest eight men on the planet own as much as the poorest 50% of the entire human race, and which is literally pushing the planet to the point where it will very soon be unable to support human life. But you always have to remember that, for people like this, the world of reckless short-termism and obscene inequality we live in is rational. Indeed, the entire Austrian project is devoted to the cause of proving that it is as close to a rational ordering of society as we can ever manage… which is why they had to devise an entire school of thought founded on the insolent rejection of evidence.

But let’s take it seriously for a moment. In simple terms, the argument – which, as will be clear, is derived directly from Austrian first principles – runs thus: to achieve a decent and sustainable standard of living, a society must be able to allocate its resources efficiently by making economic calculations. To do this you have to know what the ‘primary factors’ – the big, important resources that form the basis of all production, such as land, steel, and capital itself – are worth, and thus the best use to make of them. You derive this knowledge from prices assigned by the market.…

An Increasingly Inaccurately Named Trilogy: Episode VIII – The Last Jedi

The obvious starting point is the dualism that creatively defines the sequel trilogy, with J.J. Abrams’s faithful recitations of iconography on either end of Johnson’s far weirder and more difficult approach to doing a Star Wars. Neither director needed to do Star Wars, but for very different reasons. Abrams had already defined himself as a classically minded reinventer of classic genre tropes, and the franchise was merely a bigger version of what he’d already done with Star Trek. Johnson, meanwhile, was a rising indie visionary with ideas of his own and while jumping over and doing a big genre film would no doubt open new options for his own work, he was doing perfectly fine.

The obvious starting point is the dualism that creatively defines the sequel trilogy, with J.J. Abrams’s faithful recitations of iconography on either end of Johnson’s far weirder and more difficult approach to doing a Star Wars. Neither director needed to do Star Wars, but for very different reasons. Abrams had already defined himself as a classically minded reinventer of classic genre tropes, and the franchise was merely a bigger version of what he’d already done with Star Trek. Johnson, meanwhile, was a rising indie visionary with ideas of his own and while jumping over and doing a big genre film would no doubt open new options for his own work, he was doing perfectly fine.

There is virtually no way of describing the two where Johnson does not come across as the more interesting filmmaker. He is, frankly, a bizarre and unprecedentedly brave choice for the franchise—to put it with maximal uncharitableness, the first time a Star Wars film has ever been helmed by a real director. And it’s no surprise that the result is fundamentally unlike other Star Wars movies. We might start with the end, noting that the final shot, in which Star Wars merchandise becomes the next Guy Fawkes mask in a scene with none of the main characters, utterly removed from the main action, is simply not something that any previous film would ever have considered. It’s amazing, and we’ll return to what it’s doing, but the real jaw-dropping moment that requires us to stop and reevaluate the basic question of what a Star Wars movie is comes a few minutes earlier, in the fight between Luke and Kylo Ren. Ren directs the full force of the First Order’s weapons against one man, standing out in the salt plain, hitting him with a bunch of AT-ATs. The attack stretches on preposterously long, an act of blatant, childish overkill. And then, as the smoke clears, an unharmed Luke walks out and moves his hand along his shoulder in an imitation of a Jay-Z’s “Dirt Off Your Shoulder,” a song from a distant galaxy in the far future.

Never mind that no previous Star Wars movie do this – had Johnson done it two-and-a-half hours earlier it would have come off as a complete misunderstanding of how to Star Wars. Doing stuff like this seems to be part of why Chris Miller and Phil Lord got themselves sacked from Solo. It’s the most mind-wrenching and genuinely astonishing shot in all of Star Wars, simply because it passes off something that should be entirely outside the grammar without so much as a fuss. What on Earth had he been doing for two-and-a-half hours that made that work?

Inevitably, there’s no one answer. Indeed, the crux of Johnson’s approach is to repeatedly do small and unexpected things, none of which feel like ruptures of what Star Wars means, but all of which demonstrate a willingness to ask not only what Star Wars can do that’s new, but to ask what it has thus far lacked.…

Forward, to the Past! 2 – Episode 2: First Order of Business

Spoilers

Spoilers

Even as it complicates the Star Wars universe in some ways, the sequel trilogy clings close to the old liberalism vs. fascism dichotomy that dominated the politics of the original trilogy and prequel trilogy, and which dominates fantasy narratives generally. (See this by Phil, for instance.) The First Order’s politics is essentially contentless. They hate the Republic because reasons. They wear black and grey uniforms, and have red and black banners, and rallies, and they’re therefore fascists, and the fascists hate liberal democracy because they just do. This dichotomy, which is pervasive throughout stories of this kind (look at Harry Potter for instance) tells us something about the permissible horizons of ideology in the capitalist mass culture industries. It is this which gives rise to the syndrome I talked about in my villains essay, in which I point out (amongst other things) that villains are usually the only people in stories like this who are trying to fundamentally change the world.

Actually, the original trilogy scores slightly better on this than many other such narratives. It is set in a period when the fascists have already won, and the people trying to change the world are the good guys. While it set the fascism/liberalism dichotomy template for a generation of fantasy narratives, Star Wars actually had a marginally better version to offer. The odd thing is that, while consciously more ‘right on’ (or does one day ‘woke’ these days?) in many ways, the sequel trilogy is actually retrograde in this respect, because – at least in Force Awakens – the First Order is more like a challenger to the reign of the New Republic, a splinter group, a secessionist movement.

I noted in this essay how much the First Order looks like the Confederacy. This is the spin that Force Awakens put on the old dichotomy, and it’s valuable – except that it once again positions the bad guys as the only people trying to change things, the only people challenging liberal democracy. And that’s a shame because liberal democracy needs challenging. It’s better than fascism, but that’s a low bar. The Union was better than the Confederacy, and the Civil War was worth fighting (to push for the freedom of the slaves, etc) but it’s also true that the Union was capitalist and imperialist, and that imperialism was built into its actual motives for fighting the Civil War. The Union went on to build its further expansion on imperialism, invasion, slaughter, warmongering, oppression, genocide, etc.

In the fascism/liberalism dichotomy, the baddies are almost always the only people challenging such systems. They often get to point out the hypocrisy of liberal democracy, before being proved wrong and crushed. The ideological utility of such moves doesn’t take much parsing. You eternally consign challenges to the status quo to the category of villainy and fanaticism, and to doom.

There is something to be said for storytelling – in the late teens of the twenty-first century – that is open and unambiguous about fascism being a bad thing that needs to be stopped.