The Proverbs of Hell 34/39: The Great Red Dragon

THE GREAT RED DRAGON: After thirty-three episodes named after food, we change gears abruptly to episodes named after works of art by William Blake. This episode does not designate a specific work but rather a series of four paintings in a larger series of water colors illustrating the Bible completed between 1800 and 1806 four of which have titles beginning “The Great Red Dragon.” Thankfully we still have food to illustrate this episode as part of the delightfully barmy decision to let Hannibal still cook in prison, and we can get on to the Blake works starting next episode.

THE GREAT RED DRAGON: After thirty-three episodes named after food, we change gears abruptly to episodes named after works of art by William Blake. This episode does not designate a specific work but rather a series of four paintings in a larger series of water colors illustrating the Bible completed between 1800 and 1806 four of which have titles beginning “The Great Red Dragon.” Thankfully we still have food to illustrate this episode as part of the delightfully barmy decision to let Hannibal still cook in prison, and we can get on to the Blake works starting next episode.

Although Time has on a few occasions in its history had articles on Blake exhibitions, he is not generally considered cover material, and if he were it seems unlikely The Great Red Dragon and the Woman Clothed with the Sun would be the image gone for. But for all its mild silliness, there’s a certain logic to having Dolarhyde encounter the Great Red Dragon in a print magazine, given that Dolarhyde exists in a constant tension with modernity, as we’ll get to.

The first thing to be emphasized about Dolarhyde is his intense physicality—he is, as they say, a beast. This is something of a novelty in Hannibal—there’ve been a handful of killers whose physicality has mattered in some sense (Randall Tier and Georgia Madden spring to mind), but none where the basic threat and danger of them is so rooted in raw puissance.

Finally the influence runs in the opposite direction as Hannibal shamelessly rips off Sherlock.

One step away from the outright defining image of Hannibal. It is notable, compared to other depictions of Hannibal in a cell, for its relative lushness—Hannibal’s cell is large and decorated with an ornateness that contrasts utterly with the Baltimore State Hospital for the Criminally Insane as depicted in Seasons One and Two, and he’s afforded a myriad of luxuries unlike the sparse hells usually associated with his incarceration. There are a number of reasons for the change. First, Hannibal here is a character we’ve spent thirty-three episodes with already, and does not need to be a beast at the heart of a terrible dungeon in order to be scary. Second, and somewhat contradictorily, Hannibal here is not monstrous in the same way as in previous versions. Hannibal has made much more peace with the inherent tension of revulsion and adoration the monster in a horror movie elicits. A grand room from which Hannibal grants audiences to lesser creatures is fully in line with what this version of the character is.

ALANA BLOOM: Congratulations, Hannibal. You’re officially insane.

HANNIBAL: There’s no consensus in the psychiatric community what I should be termed.

ALANA BLOOM: You’ve long been regarded by your peers in psychiatry as something entirely Other. For convenience, they term you a monster.

HANNIBAL: What do you term me?

ALANA BLOOM: I don’t. You defy categorization.

The previous episode asked whether Alana could ever have understood Hannibal. Certainly her attempted distinction between defiance of categorization and monstrosity points towards “no,” although the fault is just as plausibly Fuller and Lightfoot’s. A monster, after all, is defined precisely by its excess—it is a category denoting that which refuses to be completely categorized. (As Miéville points out, this generates the horror fanatic’s obsession with precise taxonomies of monsters, but the taxonomy always, at the last moment, collapses into something beyond mere signification.)

HANNIBAL: I’m not insane.

ALANA BLOOM: You know that and I know that. A dozen or a baker’s dozen, enough people have died.

HANNIBAL: You haven’t.

ALANA BLOOM: A promise in waiting, isn’t it? A promise you intend to keep.

HANNIBAL: I always keep my promises.

There is something slightly unseemly (but depressingly typical) about Hannibal’s specific obsession with killing Alana. His focus on it seems in excess of the circumstances, motivated by something beyond character motivation and rooted more in a desire to have Alana exist in a state of constant peril.

This cracked mirror look at Alana—which does not correspond to anything actually happening in the scene—is used to set up a cut to Dolarhyde, a level of craft in excess of previous episodes, where the dreamscape had only been used to actively signify, as opposed to facilitate the editing of the episode. This provides a good time to talk about the hiring of Neil Marshall, famed for his direction of the first two giant battle episodes in Game of Thrones. This was a big get for Hannibal, and his deployment at the start of the series’ Red Dragon adaptation was a clear effort at midseason momentum and getting new viewers to jump on. Sadly, by the time the episode aired the show had been canceled for a month.

HANNIBAL: Sanguinaccio dolce, a classic Neapolitan dessert, with almond milk. Easier on your stomach.

DR. CHILTON: Sanguinaccio dolce. You have served me this before.

HANNIBAL: One of my favorite desserts. Traditionally made with pigs’ blood. In this case, a local cow.

DR. CHILTON: And when you last made it for me?

HANNIBAL: The blood was from a cow only in the derogatory sense.

In which it is revealed that Hannibal’s predilection for jokes about his cannibalism is sufficiently strong that he keeps making them even after he’s outed. This scene ends up jarring oddly, however—it’s the only indication of Hannibal being allowed to cook while imprisoned, a decision that is both striking and ridiculous. In hindsight, it is almost certainly a mistake—a refusal to allow Hannibal’s incarceration to change the grammar of the show as much as it should.

DR. CHILTON: He is the debutante. Although he lacks your love of presentation.

HANNIBAL: More of a shy boy, this one.

DR. CHILTON: Love to hear your thoughts. What do you think about the Tooth Fairy?

HANNIBAL: I think he doesn’t like being called the Tooth Fairy.

DR. CHILTON: It’s not as snappy as Hannibal the Cannibal, but he has a much wider demographic than you do. You, with your fancy allusions and fussy aesthetics, will always have niche appeal, but this fellow, there is something so universal about what he does. Kills whole families. And in their homes. Strikes at the very core of the American Dream. Might say he’s a four-quadrant killer.

Chilton characteristically completely fails to understand Hannibal, projecting a desire for mass popularity onto him that is obviously outside his desires. In particularly classic Chilton fashion, the error is displayed proudly in the statement: Hannibal’s fussy aesthetics preclude him giving a shit about being a four-quadrant killer.

ALANA BLOOM: We lied. You wrote a book of lies.

DR. CHILTON: Not difficult to see lies flying above my head, but it is almost impossible to shoot them down.

ALANA BLOOM: Hannibal will shoot them down. He’s written a brilliant piece for The American Journal of Psychiatry.

DR. CHILTON: Everything he writes is always about problems he doesn’t have.

ALANA BLOOM: What he’s written is going to be your problem. It’s not so much an article as it is a rebuttal. He has an acid pen.

DR. CHILTON: Hard to believe an inmate’s opinion will count for anything in the professional community.

ALANA BLOOM: It’s going to count, Frederick. And it’s going to sting.

The detail of Hannibal humiliating Chilton by refuting his own diagnosis is perhaps the most entertaining of the degradations heaped onto Chilton, mostly because it highlights the sheer and irony-laden gulf in talent and class between the two of them, and the utter comedy that is the idea of Chilton sparring with him.

Depicting Dolarhyde as a literal monster of film is interesting. When Red Dragon came out in 1981, Dolarhyde’s status as an employee at a film processing plant was unremarkable, consisting merely of a clever bit of horror in response to the famed “how is he choosing them” question: he’s someone who has access to our private moments that we don’t know or ever see. Inasmuch as it’s an object worthy of scrutiny, it speaks to Harris’s consistent fascination with turning modernity into monstrosity. But in 2015, nearly thirty-five years later, his connection to film is dated—a connection less to modernity than to early 20th century modernism. (Hannibal himself, of course, presents similar issues.) He is a technological monster, yes, but he is rooted in the hauntological qualities of technology as opposed to any futuristic ones.

MOLLY: How bad is it gonna be if you stay here and read about the next one? If you stay here and there’s more killing, maybe it’d sour this place for you. High Noon and all that.

WILL GRAHAM: Do you want me to go?

MOLLY: I’d have the satisfaction that you did the right thing. He kills families. No one knows how he chooses them. What if he chose us?

WILL GRAHAM: Don’t say that. If I go… I’ll be different when I get back.

MOLLY: I won’t.

And so Fuller creates another interesting and generally compelling female character to repeatedly underuse and treat exclusively as a peril monkey. This one gets the added wrinkle of also existing mainly to get in the way of the Hannibal/Will relationship, which means that the audience is, despite her overwhelming sense of decency, nudged towards rooting against her. Ew.

HANNIBAL: Dear Will, we have all found a new life, but our old lives hover in the shadows. Soon enough, I fear Jack Crawford will come knocking. I would encourage you, as a friend, not to step back through the door he holds open. It’s dark on the other side and madness is waiting.

It is an interesting question whether Hannibal is playing reverse psychology here, or making a single action as a hedge against every contrary action he is subsequently going to take towards Will. This is mostly played ambiguously; we find out next episode that Jack allowed the letter to be sent, which leans towards reverse psychology, but Jack is not Hannibal, and it does not inherently follow that they share motivations.

WILL GRAHAM: I have to touch her. This is my design.

This becomes the most radical rewriting to remove rape in the series to date; in Red Dragon, Dolarhyde does not so much “touch” her as “have sex with her corpse.” The sexual aspect is preserved to an extent—the placement of a mirror in the labia is mentioned later—but on the whole the sexual nature of the crime is excised. It is difficult to seriously argue that this is not a dramatic improvement.

JIMMY PRICE: This won’t take long. I’ll need one reasonably-intelligent assistant, if you have one. Have you touched the bodies yourself, Mr. Lombard?

MR. LOMBARD: No.

JIMMY PRICE: Find out who has. I’ll have to print them all. Cancel the reasonably-intelligent assistant, mine just showed up.

BRIAN ZELLER: I can’t help you with your thing. I’ve got a thing.

JIMMY PRICE: What thing do you got?

BRIAN ZELLER: I’m reconstructing teeth from bite marks on Mrs. Leeds and this Mini Babybel cheddar cheese wheel from her refrigerator. Tooth Fairy was feeling peckish.

JIMMY PRICE: Come on, then. We’ll double-Dutch. Woman’s got to get in the ground.

The return of Price and Zeller—who didn’t fit in the Europe-based adaptation of Hannibal, and so are making their first appearance of the season—is done with a charming with a bit of fanfare and humor. These are minor characters—Zeller’s relationship with Will is occasionally focused on, but they are essentially insulated from the plot and serve only as entertaining means of providing plot exposition. But they are delightful.

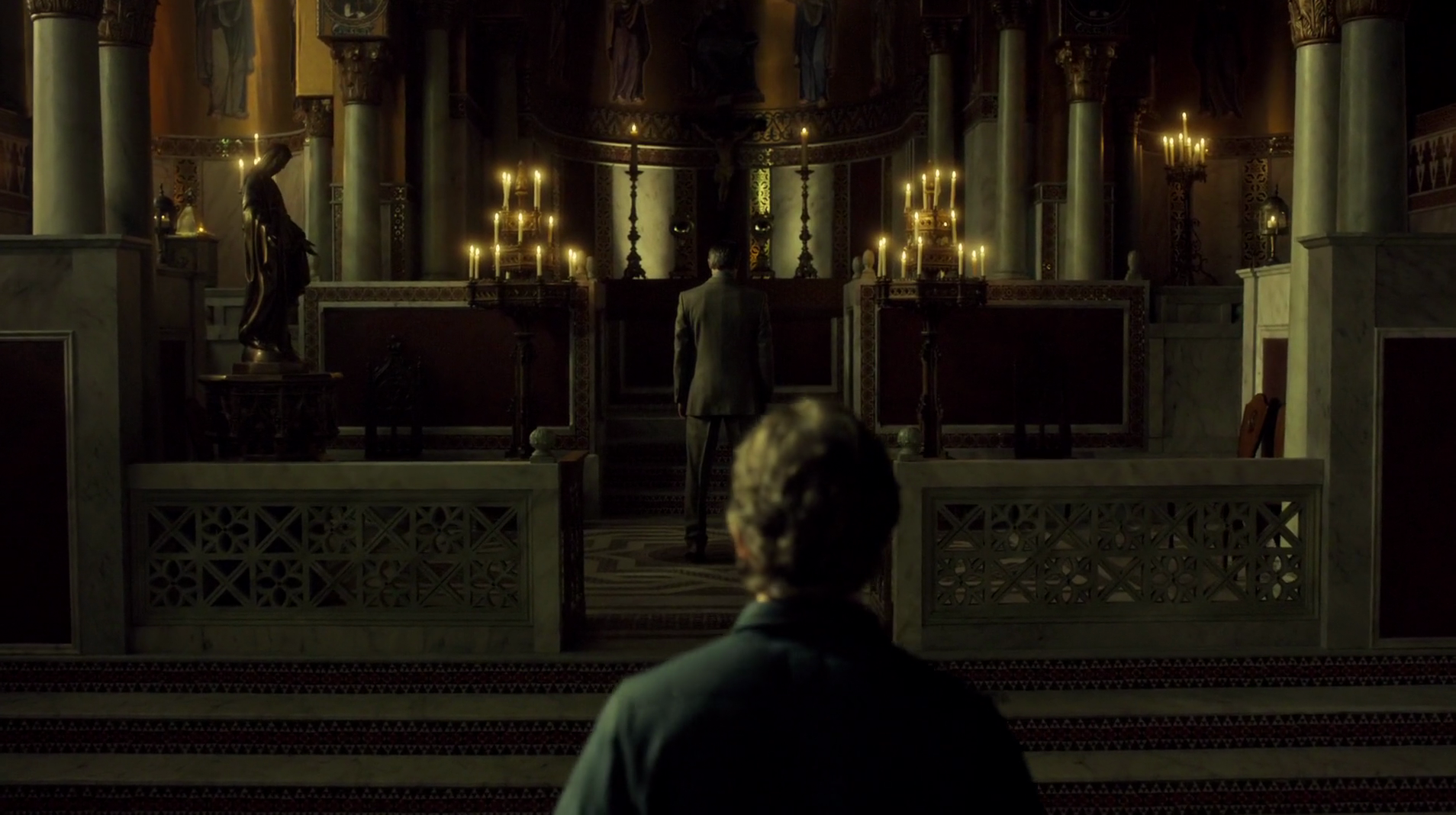

One of the ways in which Hannibal endeavors to avoid becoming visually boring in these final six episodes as all of Hannibal’s scenes are moved to a single location is to repeatedly slip into the dreamscape to position Hannibal in other locations even as he is in reality standing in his cell. This is type specimen of these shots – Hannibal in a palatial chapel, an object of reverence and power, stressing the myriad of ways in which he is not imprisoned.

WILL GRAHAM: Hello, Dr. Lecter.

HANNIBAL: Hello, Will.

Well how else was it going to end?

January 30, 2018 @ 11:10 am

“the placement of a mirror in the labia”

If I recall correctly, the mirror is placed in the labia, mouth, and on the eyes – those are all places through which another person can be taken in, or consumed if you will. Dollarhyde’s modus operandi points to a fear of losing his identity in another person – he blocks the paths through which that could happen so that they simply reflect him. In this instance, this fear of being consumed is very gendered, it’s a man fearing a woman’s power of transforming him (and, to prevent that, turning her into an object in which he can regard himself), but of course it will also play out in our main couple.

(And of course Dollarhyde makes a tragic, as it will turn out, mistake in thinking that that which consumes has power over the consumed, but that’s still a few weeks away).

January 30, 2018 @ 12:25 pm

Very interesting! And so he seeks his own transformation, encouraged and facilitated by a poweful man.

January 30, 2018 @ 11:38 am

Please don’t swap the picture of Verger choking on an eel for the correct one. As an illustration of Dolarhyde’s intense physicality it is hilariously perfect.

January 30, 2018 @ 12:23 pm

“This scene ends up jarring oddly, however—it’s the only indication of Hannibal being allowed to cook while imprisoned, a decision that is both striking and ridiculous.”

I never really noticed that but now that you point it out… utterly ridiculous. Why on Earth would he be granted such privileges? I would assume good behaviour only gets you so far when you’ve been convicted of eating people. Because of that decision later scenes depicting him affecting events despite being locked up lose their power – there’s not even a pretense of real prison sentence about his incarceration.

“But in 2015, nearly thirty-five years later, his connection to film is dated—a connection less to modernity than to early 20th century modernism.”

Interesting. Do you think he should’ve been updated, like Freddie Lounds was? Perhaps he could be a cell phone technician, gaining access to people’s private photos and videos through smartphones he’s repairing. That would work, I think.

“And so Fuller creates another interesting and generally compelling female character to repeatedly underuse and treat exclusively as a peril monkey.”

This. And what’s more, the very existence of Molly seems unfounded. She’s supposed to be this important character who anchors Will in peaceful everyday life far from Hannibal’s nightmarish realm… but we’ve never seen her before. She has no narrative weight. The mid-season time jump was probably inevitable but it still hurt the show somewhat. It’s the same problem that the famous “One year later” time jump from “Battlestar Galactica” created. It moved the beloved characters to such radically different narrative places in a matter of seconds that it’s hard not to feel thrown out of the story. And perhaps even a little cheated.

January 30, 2018 @ 4:06 pm

Re: cooking, from what I understand, he’s obtained these privileges as a form of blackmail—since Alana and Chilton lied about his sanity in order to assure he’d be institutionalized, and he went along with the lies for his own ends, he has a certain degree of power over his confinement (power that Alana takes away when she gets pissed enough later in the series). It’s been a while, though.

February 2, 2018 @ 9:27 am

Eh, makes sense, I guess. I still would’ve liked to see some degree of powerlessness/frustration from Hannibal.