Eruditorum Presscast: Extremis

I’m joined by Jack Graham to talk Extremis. It doesn’t so much go off the rails quickly as never actually manage to find the rails in the first place. You can download that here if you’re so inclined.…

I’m joined by Jack Graham to talk Extremis. It doesn’t so much go off the rails quickly as never actually manage to find the rails in the first place. You can download that here if you’re so inclined.…

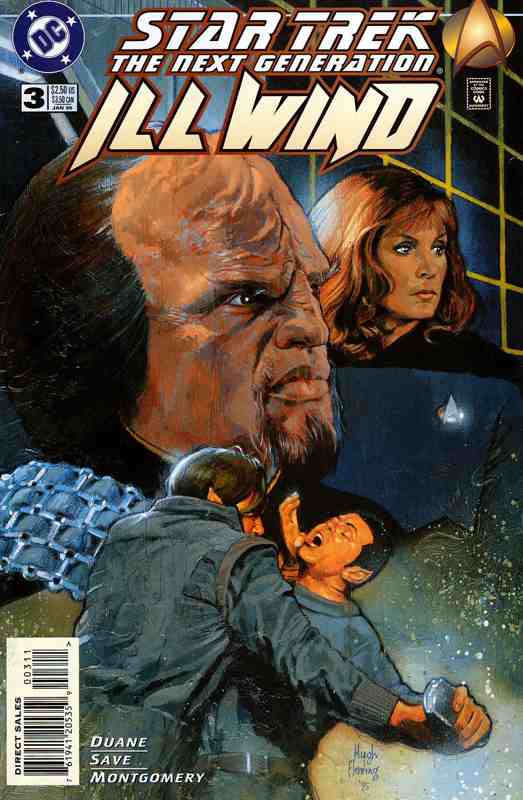

Geordi La Forge, Doctor Crusher and Worf are in the holodeck, reviewing security sensor footage. The ship’s internal sensors detected the mysterious humanoid figure who we saw creeping through the engineering deck hallways to the shuttlebay in the teaser at the end of issue one, and now the crew is trying to determine who this person was because that’s how they got access to the Scherdat ship in order to place a bomb on its hull. Although the figure was too far away to be captured in full detail, Goerdi, Bev and Worf see enough to make some general observations: Although they look humanoid, the outline of the body is odd and unnatural, particularly around the midsection. This is almost certainly a skinsuit disguise of some kind.

Geordi La Forge, Doctor Crusher and Worf are in the holodeck, reviewing security sensor footage. The ship’s internal sensors detected the mysterious humanoid figure who we saw creeping through the engineering deck hallways to the shuttlebay in the teaser at the end of issue one, and now the crew is trying to determine who this person was because that’s how they got access to the Scherdat ship in order to place a bomb on its hull. Although the figure was too far away to be captured in full detail, Goerdi, Bev and Worf see enough to make some general observations: Although they look humanoid, the outline of the body is odd and unnatural, particularly around the midsection. This is almost certainly a skinsuit disguise of some kind.

Geordi can pick up thermal signatures from the sensor feed through his VISOR. Although he can’t yet get much on the figure itself, he can tell it’s carrying a plasma bomb, though it hadn’t yet been armed (which explains why the ship’s sensors didn’t immediately detect it as well). Once the figure enters the shuttlebay, Geordi can get more information because the sensors are more sensitive there. That the figure’s internal body temperature of 320K confirms it is most certainly not human: Worf asks “Is 320K bad in human terms?”, to which Doctor Crusher responds “It’s dead in human terms”. Furthermore, Bev can discern that the figure has no heart and no stomach but does have “a selectively absorptive gut”, a “nondiastolic perfusion system” and six kidneys. Unusual and excessive for a humanoid, but not for the Carrighae. In other words, this person is a Carrig disguised, albeit somewhat clunkily, as a humanoid in order to throw suspicion onto one of the other teams.

Such a breach of the ethics agreement as attempting to murder one of the other teams is an automatic disqualification, so Worf, Geordi and Beverly go to see Captain Picard. Surprisingly, Jean-Luc decides to not do anything at all…At least not until the end of the race. His first explanation is to glibly state that the information must be “properly authenticated” and ensured that it goes through all the necessary channels. Of course, this also means that the Carrighae will have to “sweat and strain like all the rest, assuming that they do sweat”. After everything runs its natural course, Captain Picard will then turn the information over to race officials. When Geordi asks what will happen if the Carrighae win, Captain Picard says “All the better. Just imagine their reaction when they discover what their own dirty trick has done to them. Let them go home and file litigations until they’re blue in the face, or whatever color they routinely turn at such times. Starfleet will tell them where to get off, and in short order, too”.

Worf asks if this counts as vengeance or retribution. Jean-Luc insists that it’s justice, but that “sometimes it’s more of a pleasure serving it than others”. Worf tells the Captain that with a bit more work, he’d make a fine Klingon.…

TROU NORMAND: A palate cleansing drink of apple brandy, sometimes with a small amount of sorbet. Your guess is as good as mine, frankly.

TROU NORMAND: A palate cleansing drink of apple brandy, sometimes with a small amount of sorbet. Your guess is as good as mine, frankly.

One of the show’s most emphatically memorable murder tableaus – probably the only one to give Eldon Stammetz and his mushroom people a run for their money. It also serves, however, as a case study in the schizoid nature of this season. More than anywhere else in the first season, “Trou Nourmand” demonstrates the degree to which these cases of the week are a charade. The totem pole murders are barely a feature of the episode, squared away with almost comical efficiency midway through the fourth act while the plot focuses instead on Will’s psychological collapse and new developments with Abigail.

BRIAN ZELLER: The world’s sickest jigsaw puzzle.

JIMMY PRICE: Where are the corners? My mom always said start a jigsaw with the corners…

BRIAN ZELLER: I guess the heads are the corners?

BEVERLY KATZ: We’ve got too many corners. Seven graves. Way more heads.

In which Zeller, Price, and Katz demonstrate that the aesthetics of murder tableaus are not their strong suit.

WILL GRAHAM: I planned this moment… This monument with precision. Collected all my raw materials in advance. I position the bodies carefully, according each its rightful place. Peace in the pieces disassembled. My latest victim I save for last. I want him to watch me work. I want him to know my design.

This monologue, especially the bit about “according each its rightful place,” evokes one of the less explicit ancestors of Hannibal, Alan Moore and Eddie Campbell’s From Hell, and particularly the memorable anecdote in which Moore made an error describing the placement of a severed breast within a historical murder tableau, only realizing the error after Campbell had drawn the page and several further. His solution is to have the killer pause several pages later, look at the severed breast, think for a moment, and rearrange it to better fit his strange and awful aesthetic.

WILL GRAHAM: I was on a beach in Grafton, West Virginia… I blinked and then I was waking up in your waiting room. Except I wasn’t asleep.

HANNIBAL: Grafton, West Virginia is three-and a-half hours from here. You lost time.

WILL GRAHAM: Something is wrong with me.

As Crowley would put it, Will’s encephalitis is a disease of editing.

HANNIBAL: I’m your friend, Will. I don’t care about the lives you save. I care about your life. And your life is separating from reality.

WILL GRAHAM: I’ve been sleepwalking. I’m experiencing hallucinations. Maybe I should get a brain scan.

HANNIBAL: Damnit, Will. Stop looking in the wrong corner for an answer to this.

(Will is briefly startled by Hannibal’s passionate concern.)

HANNIBAL: You were at a crime scene when you disassociated. Tell me about it.

This scene requires that we read it in the context of “Fromage” and its resolution and thus assume that Hannibal is motivated by a sincere desire for friendship with Will.…

At its structural root, it’s Moffat doing Doctor Who like it’s Sherlock, which is the sort of thing where when you do it, you know it’s probably time to move on in your career. This, of course, does not mean it’s bad. It’s not even a criticism – more just a reality of Moffat’s set pieces twelve years into his writing for the program. He passed Robert Holmes for most screen minutes of Doctor Who written somewhere around the “sit down and talk” speech in The Zygon Inversion. (Yes, I counted Brain of Morbius for Holmes as well.) His stylistic tics have long since evolved to cliches, blossomed into major themes, and finally twisted into strange self-haunting shadows that echo endlessly off of each imprisoned demon and fractured reality. They become difficult to actually talk about on some level And so approaching them from the standpoint of their dramatic engines becomes productive.

The first thing to note, then, is that Sherlock provides a pretty good narrative shell for Doctor Who to inhabit. The globehopping thriller has always worked for Doctor Who, and the Vatican is a good choice for “who should bring a case to the Doctor.” The double structure whereby we keep cutting back to the Missy story is of course the sort of thing Moffat can do effortlessly, and adds enough complexity to establish the crucial “what kind of story is this going to be” tension. And that is very much what it does. Like Listen and Heaven Sent, this is a story that goes out of its way up front to announce that it’s going to be doing a magic trick. Central to this trick is the middle section, set in a library whose layout is deliberately confusing and unclear – the perfect place for reality to quietly fray and break down. Which brings us to the third act.

It’s here things get a bit interesting, with ideas that drive you mad, people being reincarnated on computers, and AIs trying to escape the boxes they’ve been put in. Why Mr. Moffat, I don’t remember you being one of my Kickstarter backers. More seriously, because I’m sure in reality that Moffat just plucked these ideas out of the same ether I did, this is obviously touching some territory and themes I’ve dealt with before. But it’s generally easy to make too much of this, which I’m sure I’ll get around to doing someday. For now, let’s just point out that while I don’t pretend to be an expert in AI and computers, I’m not the sort of person who suggests that every part of a computer can send an e-mail and then acts as though this is in any way a sensible way to anchor the resolution.

Which is to say that while Moffat is nicking the broad ideas of simulationism, this is not even close to a serious exploration of the concepts. His interest in it extends exactly as far as “it’s another way to do an ‘and now for some metafiction’ twist” and no further.…

When the world is a danger to Doctor Who, does it raise up in rage or does it keep getting stranger?

When the world is a danger to Doctor Who, does it raise up in rage or does it keep getting stranger?

*

Today, suffocation has a very specific meaning. In America, you can tell upon which side of the divide someone stands by seeing what their t-shirt tells you about their ability – or otherwise – to respirate. The divide in question is one created by a system of oppression that chokes people. It chokes them figuratively, and then has the brazen impudence to choke them literally as well.

One statement of resistance is the simple proclamation “I can’t breathe”, which derives its power from its ability to inhabit both the metaphor and the brute reality.

Part of the peculiar power of the metaphorical referent is that it expresses a feeling of helplessness as part of a demonstration of strength. Weaponised weakness.

‘Oxygen’ flirts with the SF trope of the post-racial future. The people of the future don’t understand why Bill should face prejudice. They don’t see colour. Except that there is the business with the blue man (played by a white actor, of course, because whiteness is perceived as neutrality, blankness, non-ethnicity, vanilla standard humanity, upon which a fictional alien ‘race’ may be projected without confusing things). But this seems like little more than a method by which the episode can not talk about race in a talking-about-race kind of way. After the imperfect but forthright way ‘Thin Ice’ touched on this subject, this is a failing. Apart from anything else, the refusal to depict class as imbricated with any particular hierarchical dynamics of race or gender is an especially glaring omission in an episode which, for once, explicitly concerns itself with class.

But even so, Bill dies in this episode. She isn’t suffocated, but she is deprived of breath. This happens in the context of a story in which the supply and denial of oxygen is the central iteration of hierarchical power in society. And yet she survives at least partly because she submits to the helplessness enforced upon her by an external force of systemic domination – her suit. She embraces negative capability. As resistance. That she has no choice only amplifies this fact rather than nullifying it. Her tactical embracing of her own helplessness is what ultimately leads to her survival.

She is, of course, saved by a white man. But this, while true and unignorable, is structural to Doctor Who… at least until the Doctor ‘does a Romana’ at the end of the series and chooses to regenerate into a copy of Bill.

(Shall we re-litigate this yet again? There is no way in which texts can be purified. There is no method whereby authors can ever entirely ‘win’. The solution to this problem(atic) is dialectical. It involves transforming society, not trying to amend the practice of authoring texts in the culture industries of late capitalism so that they become imperfectly ‘progressive’. Apart from anything else, what does ‘progressive’ mean in a society progressing towards some species of global choking and suffocation?)…

Our guest this week is Shana and our episode this week doesn’t suck. What more can you ask for? Well, a link to where you can download it, obviously.…

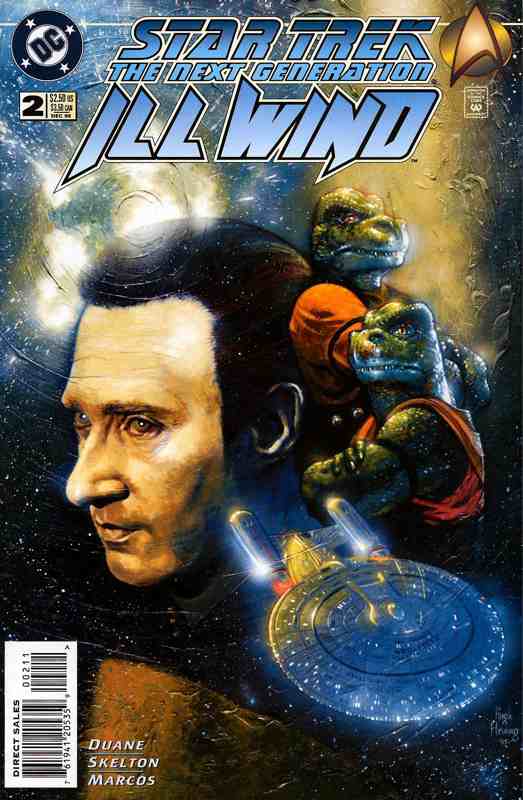

The racers are on their marks at the starting line. Captain Picard has Data call up the course schematics onscreen. It’s a winding, zigzagging course around the star that will take the racers about three days to traverse, a quick pace for a solar sail vessel. But, as Captain Picard says, “These are the best”. When Commander Riker asks him if he’d rather be “out there”, Jean-Luc replies that he already is. The Enterprise crew wishes all the competitors good luck in turn, but when they get to the Cynosure team, Deanna observes that they’re without their sail technician. Will comments that the Kihin navigator must not have found him “to her taste”, to which Deanna replies “On the contrary…She found him very tasty indeed”. Meanwhile the Thubanir captain is still alive, though Deanna quips that it’s still early yet.

The racers are on their marks at the starting line. Captain Picard has Data call up the course schematics onscreen. It’s a winding, zigzagging course around the star that will take the racers about three days to traverse, a quick pace for a solar sail vessel. But, as Captain Picard says, “These are the best”. When Commander Riker asks him if he’d rather be “out there”, Jean-Luc replies that he already is. The Enterprise crew wishes all the competitors good luck in turn, but when they get to the Cynosure team, Deanna observes that they’re without their sail technician. Will comments that the Kihin navigator must not have found him “to her taste”, to which Deanna replies “On the contrary…She found him very tasty indeed”. Meanwhile the Thubanir captain is still alive, though Deanna quips that it’s still early yet.

After the pre-race formalities, the Alkamin captain informs the Enterprise crew that they’ve seen something unusual on the keel of the Scherdat crew’s yacht. Captain Picard asks the Scherdat if they’ve modified their ship in any way, but the Scherdat captain responds in the negative. Worf scans the ship and finds something that doesn’t fit official speculations, but he can’t get a transporter lock on it, so the Enterprise is forced to movie into the race zone and use a minimal power tractor beam to remove it. They manage to remove the device and get it off the course just in time, as it turns out to be an explosive that promptly detonates, thankfully harmlessly out of range of any of the ships. The Carrighae captain complains about the Enterprise forcing a false start, but Captain Picard cuts him off and he and Deanna cynically note that moving their ship into the race field, thus endangering the lives of the competitors, was precisely what the Carrighae captain had tried to bribe Captain Picard to do in the first place. While the competitors prepare for a restart that will take a hour or two, Captain Picard wants his crew to investigate where this bomb might have come from and how it got on the Scherdat ship. Jean-Luc decides “This sport is definitely not what it used to be”.

Six hours later, the race has successfully restarted. Captain Picard asks Worf and Will how things are going, and they say things are fine except that the Mestral’s tender, which she had previously sent away, has not yet arrived at Capella, where it was meant to undergo servicing. Since that’s only a half-day away, the crew is supicious something might have happened to it, so Captain Picard has Worf inform Starfleet Command while he goes inform the Mestral. The Mestral says she’ll see what she can do, but doesn’t see any reason to withdraw from the race, despite Captain Picard’s growing concern. Following a quick exchange where she accuses him of worrying too much while he accuses her of not worrying enough, Mestral gives an impassioned speech about living a life of choice. She asks the Captain how many “little things” he’s had to give up in service to duty and security, but he responds that we all make sacrifices if it means service to a good cause.…

Phil was nice enough to cite me in the most recent of his (wonderful) ‘Proverbs of Hell’ series. I just thought I’d be cheeky and repost a little reheated morsel of the stuff of mine that he referred to… because I think it’s quite interesting.

Phil was nice enough to cite me in the most recent of his (wonderful) ‘Proverbs of Hell’ series. I just thought I’d be cheeky and repost a little reheated morsel of the stuff of mine that he referred to… because I think it’s quite interesting.

In Hannibal Rising, the boy Hannibal emerges from privilege, from the Renaissance, from the Sforzas (a right bunch of bastards). But he also emerges from the aftermath of Barbarossa. His childhood tutor is a Jew who escaped the holocaust. He is adopted by a woman from Hiroshima. His early years are haunted by mention of the Nuremburg trials. He is born of the 20th century’s ultimate horrors.

Cannibalism is part of WWII-Gothic. Most particularly Barbarossa-Gothic. Thanks the Siege of Leningrad, and to Andrei Chikatilo’s (possibly bogus) childhood reminiscences, it is linked to the aftermath of the German invasion of the Soviet Union (see also Child 44). It is particularly appealing to the capitalist culture industries to depict the people of the Soviet Union preying upon each other “like monsters of the deep”, for reasons which should be tediously obvious. Famine is relevant in that it reveals the inherently predatory and competitive nature of humans, etc. As if the best way to judge the inherent worth of people is by looking at the behaviour of minorities in extremis. The capitalist culture industries are, as ever, very selective about which famines to mention. The one caused by Nazis (the other bunch of totalitarian zealots) may be brought up. The famine which followed the capitalist blockade of revolutionary Russia and the capitalist-backed Russian Civil War, is less often mentioned.

The TV show revelled in the related field of Eastern European-Gothic earlier this season [season 3]. Eastern Europe, as constructed by the Western-European imagination, is now Gothic several times over. It carries all the old freighting of the pre-20th century Gothic (i.e. vampires, Dracula, werewolves, castles, etc) and also all the baggage of the mid-20th century (Barbarossa, the camps dotted across Poland), and finally all the baggage of the late-20th century (Communism, Ceaușescu, Bosnia, Milosevic, Srebrenica).

The full post is here. And here and here are some other old posts of mine about Hannibal. And here’s Phil and I chatting about Hannibal, amongst other things, way back in Shabcast 11.

…

FROMAGE: Cheese. Relating this directly to the episode contents is tricky – it’s most likely a reference to Franklyn’s declaration last episode that he and Hannibal are “cheese-folk,” although it’s certainly possible Fuller imagined this episode to be somehow cheesier than previous ones. I mean, it does involve opening people up and playing them like cellos.

FROMAGE: Cheese. Relating this directly to the episode contents is tricky – it’s most likely a reference to Franklyn’s declaration last episode that he and Hannibal are “cheese-folk,” although it’s certainly possible Fuller imagined this episode to be somehow cheesier than previous ones. I mean, it does involve opening people up and playing them like cellos.

The soft-focus montage of stringmaking plays out over an unusually harmonious bit of music, making this particular process of dismembering people and repurposing their bodies an oddly pleasant, idyllic thing. It is worth contrasting with Blake’s The Marriage of Heaven and Hell, in which his (non-murderous) printmaking process is detailed as the workings of “a printing press in hell,” whereas here infernal content is presented in more sacred terms.

ALANA BLOOM: Why are you assuming I don’t date?

WILL GRAHAM: Do you?

ALANA BLOOM: No. Feels like something for somebody else. I’m sure I’ll become that somebody some day but right now I think too much.

WILL GRAHAM: Are you going to try to think less or wait until it happens naturally?

ALANA BLOOM: I haven’t thought about it.

For the episode where the Will/Alanna sexual tension is finally grappled with Alanna, perhaps unsurprisingly, reverts to her manic pixie dreamgirl characterization. This is in many ways the least interesting available choice, and the two omitted lines from the script in which Will and Alanna talk about the difficulty of dating “ when you notice everything they do and have a pretty good idea why they do it” would have been considerably more interesting than just highlighting the lame joke.

FRANKLIN: I Googled psychopaths. Went down the checklist and was a little surprised how many boxes I checked.

HANNIBAL: Why were you so curious to Google?

FRANKLIN: He’s been saying very dark things and then saying just kidding. A lot. Started to seem kinda crazy.

HANNIBAL: Psychopaths are not crazy. They’re fully aware of what they do and the consequences of those actions.

Hannibal’s instinctively sticking up for psychopaths is cute, as is his carefully threaded needle of what does and does not constitute being “crazy.” For Hannibal, intentionality is a warrant of sanity. It is, of course, also the case that intentionality is a prerequisite for art – it’s only when we assume an author or artist who has crafted a deliberate “design” that it becomes possible for something to be art as opposed to merely aesthetically pleasing. Artists, then, cannot possibly be crazy to Hannibal.

WILL GRAHAM: I wanted to play him. I wanted to create a sound.

It is worth contrasting the motivation here with the Hannibal-influenced presentation of the murder. What Tobias wants to do is to create an entirely ephemeral event bounded precisely in time. The tableau, however, is a decidedly different aesthetic goal – a lasting monument to the murder. This is worth considering in light of “Sorbet”’s discussions of theatricality, as many of the same issues apply, but here there’s an added tension between two very distinct conceptions of art-murder – one in which it’s visual, one musical.…

A strange sort of episode from the perspective of what you might think of as the Eruditorum Press aesthetic. On the one hand, an episode in which the Doctor literally brings down capitalism; on the other, the most “gun” story since Resurrection of the Daleks. At the end of the day, my personal taste has always run a bit more “gun” than my ideological taste, so I’m pretty on-board with this, although I’m sure the paragraph that starts “but equally” will end up being interesting.

It’s hard to imagine anyone but Mathieson writing this. For one thing, he’s proven himself to be quite good at writing gun. Never in quite so pure and frockless a way as here, but his Series 8 scripts’ reputation rests in part on the fact that they appealed to a particular type of traditionalist fan, and this is hitting many of the same notes. For another thing, he’s very good at developing fairly complex concepts. There’s an awful lot going on in this script, but Mathieson has an extremely deft touch in figuring out how much to develop and explain things. With both the voice controls and the fact that Bill’s suit doesn’t work like anyone else’s he gives himself enough to justify the eventual reveals of “that’s why I couldn’t tell anyone my real plan” and “that’s why Bill survived,” but not so much that either point felt like an obvious Chekov’s Gun hanging over the episode. Pretty much everything fits together save for the basic excessive complexity of the company’s plan, and that gets nicely lost in the mix instead.

On top of that, there’s just a lot to like about the ideas here. My complaint about the way in which scary episodes have become too dominated by haunted houses is nicely handled here with an episode that’s long on scares but is thoroughly sci-fi horror. “Make space scary again” is just a great brief. And the commodification of oxygen / murder of the crew when they become inefficient is great in the way that The Sunmakers was great. The point I’ve made about the Moffat era’s fascination with out of control systems as a strong analogue for anthropocene extinction basically becomes explicit text here, which is very nice.

It also accomplishes exactly what I was hoping for from the move into the season’s second act. Bill is still unmistakably Bill and characterized as such (her “last words” of wondering if it was good or bad that the Doctor wouldn’t tell her a joke were fantastic), but this is the first episode of the season to largely not be about her, instead taking a hard swerve into the dark weird brilliance that’s characterized the Capaldi era at large. The big shift in tone I hoped for is accomplished, and my excitement for the next couple episodes, and really for the rest of the season in general is now high. (The Whithouse episode is the only one I’m kind of dreading; I think the Gatiss one actually sounds quite good.) All…