Shabcast 29 – Wheelers Beware Girls Who Ask Questions

The Shabcast is back.

The Shabcast is back.

Shana guests again, to talk about 80s fantasy cinema classics Return to Oz and The Neverending Story.

The Shabcast is back.

The Shabcast is back.

Shana guests again, to talk about 80s fantasy cinema classics Return to Oz and The Neverending Story.

There was a child once long ago who went into the woods outside Kokiri Village. The child was looking for someone, and was very sad because all of their friends had gone away, and they thought that they didn’t have any. As it came to be, these woods were enchanted, and it was said strange and mysterious things happened to those who travelled through them. Some of the village people thought these woods had been the dwelling-place of the Old Ones in the time no-one could remember anymore, and that their spirits and memories still haunted those same woods.

There was a child once long ago who went into the woods outside Kokiri Village. The child was looking for someone, and was very sad because all of their friends had gone away, and they thought that they didn’t have any. As it came to be, these woods were enchanted, and it was said strange and mysterious things happened to those who travelled through them. Some of the village people thought these woods had been the dwelling-place of the Old Ones in the time no-one could remember anymore, and that their spirits and memories still haunted those same woods.

The child searched high and low, near and far, but couldn’t find any trace of the person they were looking for. Then, the child found a cave inside a hill they had never explored before. Supposedly, this cave opened up into a gigantic hole, and the child fell in. That was the last anyone ever heard of them. Some say the child found the kingdom of the faeries who are thought to live inside that hill, and that it was those same Good People who raised that child, and that they remain inside that hill to this very day.

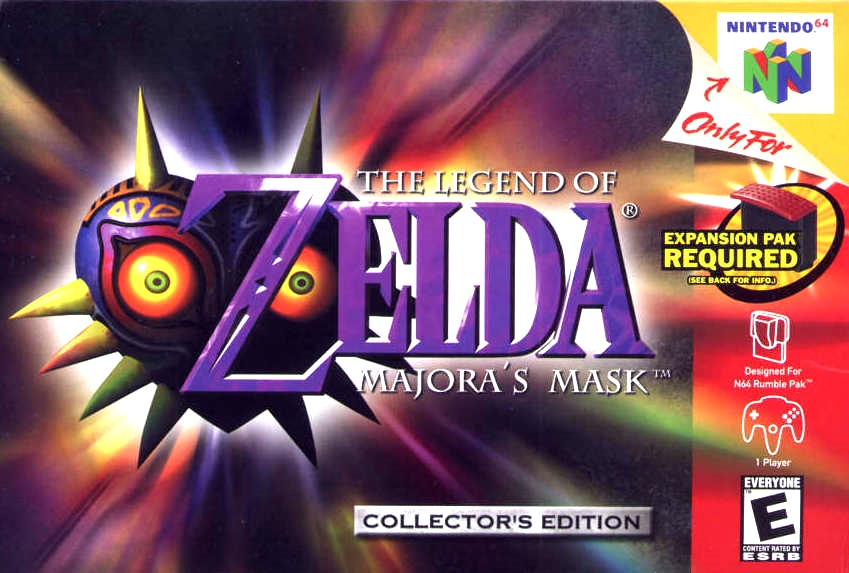

From its outset, The Legend of Zelda: Majora’s Mask is brave. The first explicitly direct sequel in the series’ history since Zelda II: The Adventure of Link, and a sequel to the overwhelmingly successful and beloved The Legend of Zelda: Ocarina of Time to boot, there was a lot riding on this game, especially after director Eiji Aonuma was tasked with designing the entire thing from scratch in under a year. Yet before the game even starts, Majora’s Mask immediately sets about distinguishing itself from its illustrious predecessor in some very dramatic ways. The most obvious, of course, being the fact that the iconic Legend of Zelda sword-and-shield emblem and regal gold background adoring the box art of every game since A Link to the Past has now been replaced by an entheodelic maelstrom (or, prophetically, the main cast in the New Nintendo 3DS version) and the piercing gaze of the titular Majora’s Mask. This continues into the game’s opening moments: There are many ways in which one can note the Peter Pan influences in The Legend of Zelda, from Kokiri Village in the last game to Link’s tunic itself. Yet this time, Zelda has chosen to invoke Alice in Wonderland instead, and that one small change changes everything.

The literal rabbit hole is obvious, less obvious is the world that rabbit hole opens into. For the first time since The Legend of Zelda: Link’s Awakening, this Zelda is not a story about Hyrule. Instead, it is set in the land of Termina, a curious mirror universe of the Golden Land where everyone looks the same, but behaves very differently. Where Hyrule is always depicted as some kind of romanticized classic high fantasy world, Termina is in places shockingly modern, with Elizabethan and Renaissance-influenced fashion and architecture, and even a rock band.…

The_OA Exegesis is on hiatus this week, as Jane is driving across America.

But you can always listen to this, like I’ve been recently — it’s kind of fun given that “away” rhymes with OA. Suddenly, it’s like the singer is speaking to her or something, which gives it all a different sort of (yet somehow related) context.

See you next week.…

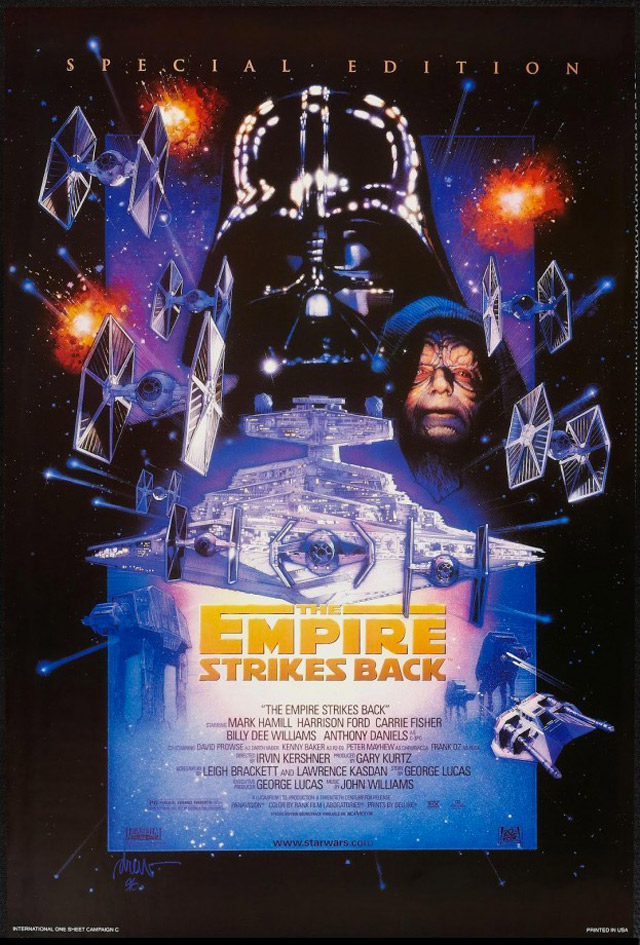

Ring theory – essentially the best read on the interrelationships between the prequel trilogy and the original trilogy to date – is based around nested correspondences among the films. The fringes of this, which pair Return of the Jedi with The Phantom Menace and Revenge of the Sith with A New Hope, are an inherently tricky business, with its interpretations standing in opposition to the more intuitive approach of reading The Phantom Menace and A New Hope as roughly analogous. But the middle, in which Attack of the Clones and The Empire Strikes Back are read as fundamentally related films, is a rock solid bit of interpretation that pays considerable and rewarding dividends.

Ring theory – essentially the best read on the interrelationships between the prequel trilogy and the original trilogy to date – is based around nested correspondences among the films. The fringes of this, which pair Return of the Jedi with The Phantom Menace and Revenge of the Sith with A New Hope, are an inherently tricky business, with its interpretations standing in opposition to the more intuitive approach of reading The Phantom Menace and A New Hope as roughly analogous. But the middle, in which Attack of the Clones and The Empire Strikes Back are read as fundamentally related films, is a rock solid bit of interpretation that pays considerable and rewarding dividends.

The most obvious similarity is structural: both films spend their middle sections alternating between two roughly equally weighted storylines, to the point where they very clearly have two protagonists, in this case Luke and Han. This is most interesting in terms of Han, whose upgrade to co-lead serves as confirmation of his moral centrality to whatever the saga is doing in this second trilogy. And in this regard, the most interesting thing about The Empire Strikes Back is its ending, with Han encased in carbonite. Sure, it’s not the only massive misfortune to befall our heroes by the end, what with Luke being maimed and all, but he’s already got a proesthetic by the end. The change that has consequences and that provides the direct hook going into Return of the Jedi is Han being taken off the board. After all, our case for Han’s centrality to A New Hope was rooted in a willfully silly reading of it in contrast to the prequel trilogy. In terms of the film’s own concerns, Han is a secondary character introduced well into a film that’s almost entirely about Luke’s journey. Here, however, his removal from the narrative is a deforming crisis.

Which brings us to the big difference between Attack of the Clones and The Empire Strikes Back. Where Attack of the Clones was liberated by its status as the middle portion of a trilogy, The Empire Strikes Back is constrained by it, and especially by the fact that it has to be the middle part of a trilogy whose first part was made under a completely different mythology and without the assumption that it would be part of a trilogy. We’ll come to the biggest consequence of this in good time, but for now I want to look at the ways in which this means the film has to set up a new status quo without it seeming like setup, which is the lengthy opening on Hoth, the primary narrative purpose of which is to quickly reconfigure the relationship among the principal characters so that Han/Leia is a more obvious ship than Luke/Leia and reaffirming Han’s loyalty by having him abandon his plans to leave in order to rescue Luke. (Arguably this makes Han/Luke the most reasonable ship of all, but never mind.) This mostly gets hidden behind what’s admittedly the best action sequence of the original trilogy, but it’s still flagrantly what Hoth is there for.…

Spoilers

Spoilers

Orson Krennic, director of the Death Star project, is a middle manager type who has achieved a position of authority above his abilities, possibly owing to his pre-existing relationship with engineer Galen Erso. He climbed the greasy pole owing to his association with a brilliant technician, and their partnership working on a prestige project. He’s ambitious and unscrupulous, but also essentially inadequate. He spends the entire film playing catch-up, being bounced between various superiors, looking for recognition, taking his frustrations out on others, and generally failing.

Tarkin’s attempted usurpation of Krennic’s control over the completed Death Star looks like a cynical power-grab, but could as easily be seen as a sensible management move. As Tarkin correctly notices, Krennic is not suited to a command role. In any case, Krennic’s shocked outrage is ludicrous given that this is just how the Empire works. His own successes come from appropriating the work of others, yet he has the temerity to feel aggrieved when his own work is appropriated. Moreover, the usual way you rise in the Empire is by showing more ruthless unscrupulousness than the other ambitious drones. You ‘work towards the Emperor’, and fuck over any competitors as you ascend. Then you get to preach against ‘ambition’ to those lower than you. It’s social-darwinism as a government system, and is yet another clear indication – and an unusually acute one – that the film sees the Empire as a clear analogue for Nazi Germany.

(The Nazi state was similarly based on this kind of wasteful infighting between multifarious bureaucrats with overlapping remits. And this was deliberate. It was doctrinal. Hitler believed the best way to get results was to set ambitious men against each other. Their epic pen-pushing battles over spheres of responsibility were supposed to mirror natural selection, the struggle for supremacy inherent in all life, or something.)

In Rogue One, it is strongly implied – in a flashback sequence of Jyn’s that adds nothing to the plot – that Krennic knew Galen and his wife, not only professionally but socially, before Galen fled imperial society. Krennic then spends years looking for him, to bring him back onto a project that could manage without him. The first thing he does, despite his stated intention of taking Galen’s wife and daughter alive, is to kill his wife. He hardly needs to, given the situation. Unable to find the daughter, he basically forgets about her. She’s out of Galen’s life. It’s fairly clear: Krennic wants Galen all to himself.

Despite claiming that Galen is a terrible liar, he allows himself to be fooled by Galen’s resigned-act for two decades. He has to be informed (in a roundabout way) of the obvious – that Galen is the traitor – by someone else. His refusal to see Galen’s treachery before then causes him all the career problems he spends the entire film coping with. Upon learning of Galen’s betrayal, he stages a public humiliation and punishment for Galen, killing everyone but him.…

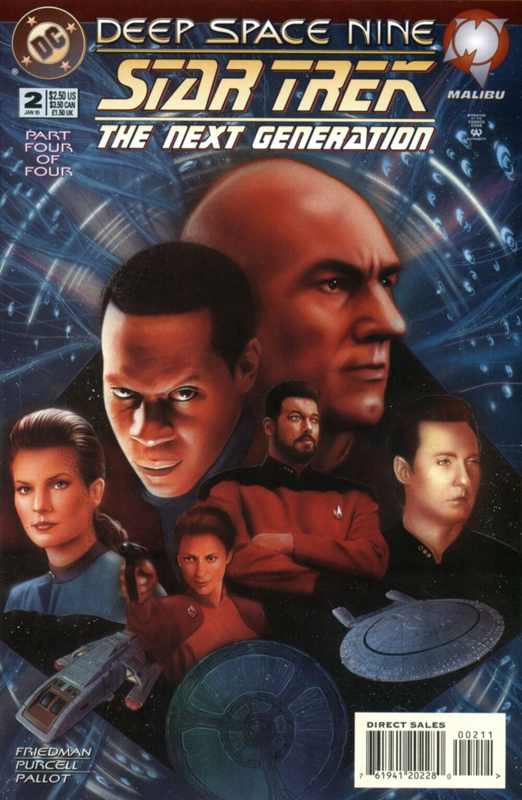

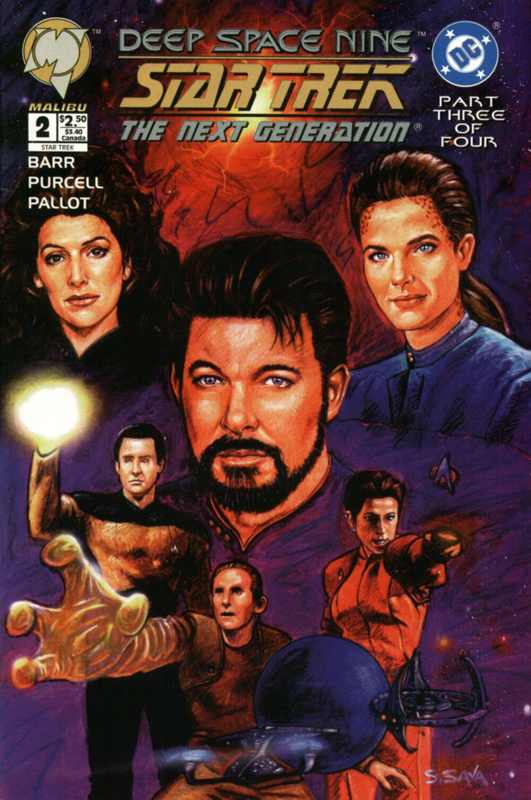

The Othersiders are gloating at having captured Data, Odo and Deanna. They order them to drop their weapons, which they do, but not before Data sets them to overload, causing yet another terrific explosion. The scattered away team uses the opportunity to kick massive amounts of ass, with Data punching people square in the gut with the full brunt of his android strength, Deanna unleashing sick karate moves and Odo turning into an awesome sludge monster to dispatch the rest. In sludge monster form, Odo praises Deanna’s fighting skills in a tone that, if I didn’t read him as asexual and aromantic, could almost be construed as a come-on. Deanna brushes it off by saying Worf trained her.

The Othersiders are gloating at having captured Data, Odo and Deanna. They order them to drop their weapons, which they do, but not before Data sets them to overload, causing yet another terrific explosion. The scattered away team uses the opportunity to kick massive amounts of ass, with Data punching people square in the gut with the full brunt of his android strength, Deanna unleashing sick karate moves and Odo turning into an awesome sludge monster to dispatch the rest. In sludge monster form, Odo praises Deanna’s fighting skills in a tone that, if I didn’t read him as asexual and aromantic, could almost be construed as a come-on. Deanna brushes it off by saying Worf trained her.

On Deep Space 9, Miles and Geordi have figured out what’s causing the Wormhole to throw a fit. It turns out it’s being assaulted by a certain kind of waveform, being broadcast simultaneously from two different stations: One in the Alpha Quadrant and one in the Gamma Quadrant. Miles figures that if they could knock at least one of those out, the Wormhole would go back to normal. Captain Picard doesn’t want to send another away team, and Commander Sisko immediately finishes his thought by setting the target on the station on this side. On the other side, Odo, Deanna and Data have unfortunately become outnumbered, but then, just in the nick of time, they’re beamed out by the remaining away team members, who have commandeered an Othersider ship in their absence. Commander Riker is quick to give praise where praise is always due by making it known that it was Jadzia Dax who hacked into the transporter network, allowing her to find them and pull them out.

Things are, unfortunately, decidedly less rosy on Bajor. Out of sandbags, the locals abandon the waterfront and make for higher ground as the inescapably rising tide of the ocean makes its way ever higher. Some disgruntled Bajorans curse the Wormhole, wishing it had never been discovered. The leader of the Provisional Government contacts Commander Sisko, confessing his feelings of hopelessness. He’s finding it hard to refute the claims of his people that the Womhole closing is the will of the Prophets, and that all outsiders should leave. Sisko begs him to stay strong, declaring that his people will provide the proof he needs, but even his excellency begins to doubt the Commander: After all, he’s not Bajoran. Commander Sisko stresses to Captain Picard that this is a desperate man, and furthermore a man who does not despair easily.

Soon though they’re interrupted by a communique from Major Kira sent via a relay buoy: She calls Commander Sisko to let him know that the away team has rescued the admirals and are on their way back, but they’re being chased by the Othersiders. On the ship, we see they’re taking heavy fire, but a quick evasive maneouvre from Kira that she picked up during the resistance gets her out of a jam, and some praise from Commander Riker.…

Before we begin, I’d like you to reach out and touch the screen you’re reading this from. Is it hot or cold to the touch? Glossy or matte? I bet it’s hard. You wouldn’t want to put your hand through this “glass” even if you could get it fixed for free. Notice how your hand obscures the light.

Before we begin, I’d like you to reach out and touch the screen you’re reading this from. Is it hot or cold to the touch? Glossy or matte? I bet it’s hard. You wouldn’t want to put your hand through this “glass” even if you could get it fixed for free. Notice how your hand obscures the light.

Close your eyes, and let out a faint breath, little more than a hisssss. Remember this feeling.

I’ll wait.

Remember. You know who you are.

Chapter Two

The Statue of Liberty is formally known as La Liberté éclairant le monde – Liberty Enlightening the World. That’s a great name. In the previous essay, we talked about the symbolism of eyes and the metaphor of sight in The_OA. This is a show that is not just concerned with the visible plot or what is “literally” happening, but also (and moreso, I think) with the invisible meaning we can derive from the text (including the text of our lives). The_OA provides a window to such inner workings through the repeated use of certain thematic elements, so when Chapter 2 opens up with an image of the EYES of the Statue of Liberty, becoming visible under the influence of photo developing chemicals as clear as WATER (another important motif in Chapter 1), I think it’s trying to signal something important. More important than just a location for some of the plot to take place in.

And there are a lot of neat referents around La Liberté in this chapter. Perhaps most obviously, she appears in a dream to Prairie, where she’s climbing the face of the statue, right over her eyes, and then suddenly she is somehow inside Liberty herself, back-lit by the Crown’s windows, and it is here she finds her father holding many candles deep in the dark. Prairie believes this is more than a dream – after all, she can see in this dream… and she’s having nosebleeds (when Prairie cleans it up in the bathroom, running the Water in the sink, Nancy comes in and says, “Let me see it in the light”) – and as such she takes it as a premonition, as if she were clairvoyant.

To get to Liberty, Prairie takes a Greyhound bus – greyhounds are sight hounds rather than scent hounds. She crosses over water in a Ferry (we’ll go back to this) to get to the Island (and we’ll go back to this), where we see all kinds of people milling about taking pictures (remember the picture of Liberty at the beginning, and young Nina having her picture taken with the Johnsons), and many more are wearing crowns, holding torches, as if everyone but Prairie herself were an avatar of Liberty. All kinds of little beats that incorporate Liberty into the language of The_OA: water and snow, sight and light.

And then there’s the reading of the plaque, which is the poem dedicated to Liberty by the poet Emma Lazarus (oh what a name, how apt for this show):

Not like the brazen giant of Greek fame,

With conquering limbs astride from land to land;

Here at our sea-washed, sunset gates shall stand

A mighty woman with a torch, whose flame

Is the imprisoned lightning, and her name

MOTHER OF EXILES.…

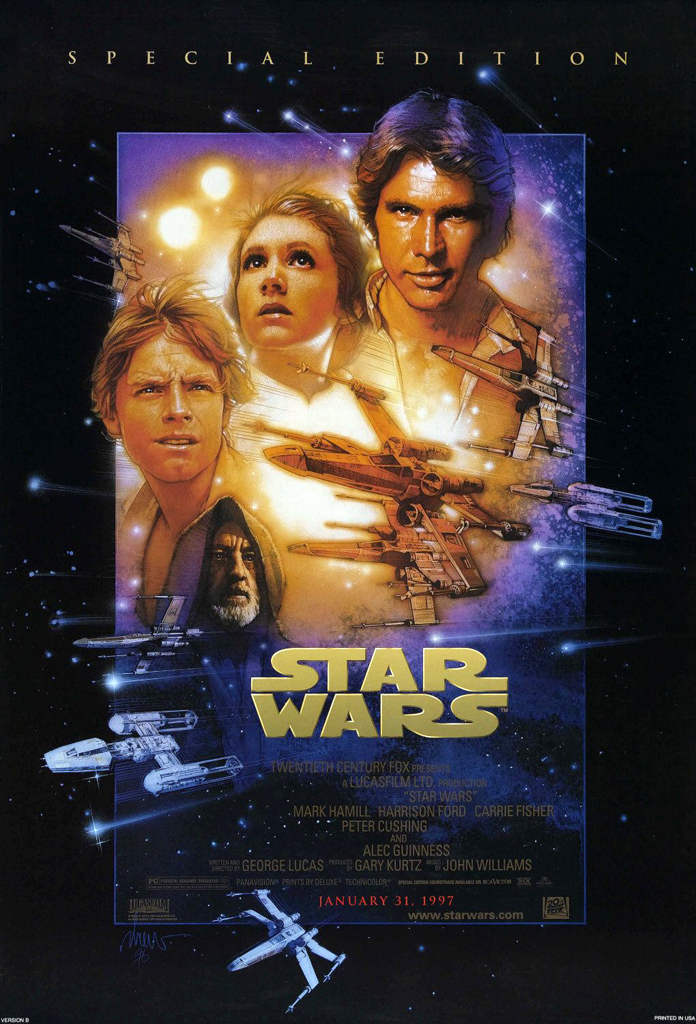

Coming at A New Hope off of the prequel trilogy, what jumps out first and foremost is how much smaller and more intimate a story it is. No small part of this is because of the twenty-eight year backwards jump in film technology, which isn’t something that can be erased even by Lucas’s extensive efforts to tinker with the original trilogy. Which I suppose are a digression worth getting into at this point.

Coming at A New Hope off of the prequel trilogy, what jumps out first and foremost is how much smaller and more intimate a story it is. No small part of this is because of the twenty-eight year backwards jump in film technology, which isn’t something that can be erased even by Lucas’s extensive efforts to tinker with the original trilogy. Which I suppose are a digression worth getting into at this point.

Obviously the special editions are easy to get cranky at. Hell, I’m on record making fun of the “redo old special effects for the DVD release” approach when it comes to Doctor Who. And the scholar in me is unsurprisingly appalled by Lucas’s active efforts to suppress the original theatrical versions of his films, to the point of denying film festivals focused on the 1970s permission to screen an original print. But these days there are multiple gorgeous reconstructions of the theatrical version up on BitTorrent for people who care, and while that doesn’t invalidate the understandable frustrations of people who spent decades wanting to watch the movie of their childhoods and not a CGI-ed over mess where Greedo shoots first and there are a bunch of cavorting aliens around Mos Eisley, it at least makes them a somewhat easier pill to swallow.

But the bigger difference between the special editions and replacing a dodgy puppet snake with a dodgy CGI snake in Doctor Who is that if you’re watching Doctor Who for its visual spectacle you have already fucked up. Whereas Star Wars has always been about raw visual spectacle in a way that makes the original trilogy’s aging into a problem for them. Without wanting to get into a (desperately tedious) debate about the superiority of traditional special effects vs CGI, it’s on a basic level understandable that Lucas would want a reaction to A New Hope other than “well that’s dated.” A uniform style of special effects across the saga is an entirely sensible desire when the saga is going to be presented as a single unit. So long as the actual historical objects are preserved in some fashion – and I’m fine with that fashion being BitTorrent – I can at least see the sense of trying to give a six-part film series a unified design.

No, the problem is simply that, as I said, you can’t actually bridge that gap. Lucas can and did narrow it, and it’s certainly less jarring to watch the special edition of A New Hope after Revenge of the Sith than it is to watch one of the restored theatrical versions, but at the end of the day A New Hope feels like a fundamentally different kind of object from any of the prequel films. It follows only a handful of characters, never moving wider than those caught in the immediate consequences of Leia’s ejecting R2-D2 and C-3PO onto Tatooine to find Obi-Wan. To its original 1977 audience, this basically appeared to be a film about a single space station.…

Yes, yet more Star Wars.

Yes, yet more Star Wars.

I still have a Patreon, as does Eruditorum Press (please give to the group before you give to me). And Wrong With Authority Ep 2 is still downloadable.

Note: This isn’t a ‘review’.

SPOILERS

As noted previously, Rogue One is a Second World War spy movie. This is probably why the Empire in Rogue One looks more explicitly Axis than ever before. And it was always pretty specifically Axis, with its Stormtroopers and its officers’ togs reminiscent of WW2 Japanese uniforms. But in Rogue One the Empire is placed specifically in the role of the baddies in a WW2 movie. I talked a bit about this last week, and Jane showed up in the comments to observe that Rogue One is also a Pacific Theatre movie, with its showdown in a beachy, tropical location, and its nukes.

The irony of the carefully scaled-down deployments of the Death Star is that their very comparatively small scale makes them spectacular in a way the destruction of Alderaan wasn’t. Alderaan just blows up. The city in Jedha, and the base on Scarif, are both destroyed locally, which means that the blasts can be observed from the point of view of the planet on which they occur. The result is, as Jane suggested, is something very visually reminiscent of the mushroom cloud, which itself – especially in this context – inevitably brings to mind Hiroshima and Nagasaki. As I myself noted in previous essays, Hiroshima and Nagasaki were always lurking in the series’ subconscious. Here they billow to the surface.

But there’s an obvious inference here. Hiroshima and Nagasaki were perpetrated by the United States. America remains the only country in history to ever actually deploy nuclear weapons – the ultimate indiscriminate killer, and therefore the ultimate war crime – against civilians as part of an actual conflict. Again, the implication of the US in the crimes of empire, of the twentieth century’s greatest horrors, has always lurked in the series. Here, again, it becomes more open than ever before. The scaling-back of the Death Star’s deployment makes the semiotic effect less bombastic, and hence less obscure. The Death Star becomes the Enola Gay, dropping Little Boy and Fat Boy on Jedha and Scarif. Consequently, the Empire is implicitly compared to the United States. Whereas before it has sometimes looked like the British Empire or the Confederacy, here it’s the USofA herself, and at the height of the good war and the greatest generation. More pertinently, it is the US at the historical moment when it became the world’s greatest superpower, which is another way of saying the world’s most powerful empire. This isn’t exactly coherent… you could certainly suggest that it looks like America attempting to put its own crimes onto the victims of those crimes… but sometimes incoherence is more eloquent. There is as much power in the implied association as in any implied victim-blaming, especially when you consider that there are other ways in which Rogue One flirts with implying quite a strong critique of US imperialism.…

Commander Riker orders the ship to turn around immediately, but of course we can’t do that. If they go back through the Wormhole too quickly, the circuitry that allowed the Runabout safe passage in the first place might be damaged. So Will thinks fast, has the crew divert all power to shields and beam over to the other Runabout (the one that carried the admirals’ party). This shouldn’t be possible because transporters famously can’t penetrate shields, but whatever. And naturally, this plan doesn’t work either as the Evil Aliens soon catch onto it and beam everyone aboard themselves in a stasis field. Because captures and escapes are just how serials work.

Commander Riker orders the ship to turn around immediately, but of course we can’t do that. If they go back through the Wormhole too quickly, the circuitry that allowed the Runabout safe passage in the first place might be damaged. So Will thinks fast, has the crew divert all power to shields and beam over to the other Runabout (the one that carried the admirals’ party). This shouldn’t be possible because transporters famously can’t penetrate shields, but whatever. And naturally, this plan doesn’t work either as the Evil Aliens soon catch onto it and beam everyone aboard themselves in a stasis field. Because captures and escapes are just how serials work.

So after that bit of padding, we get some exposition. Because, again, serials. These Aliens, hereafter the titular Othersiders, explain to the team that they are pissed off at people from the Alpha Quadrant intruding on space they claim is theirs, and they’re determined to strike back. Back on our side, Captain Picard suggests that he and Commander Sisko pass the time waiting for word from the away team by helping out with a humanitarian mission on Bajor. Because this team can’t have the DS9 commander appear too competent or confident, an anxious and uncertain Sisko asks if that’s wise, but eventually comes around to the idea. In the infirmary, Doctor Bashir is still trying to ask Doctor Crusher out, but he stresses he only wanted to ask her for help about what to say to Jadzia Dax, given Beverly’s prior experience with Trills. Julian tries to dance out of it, of course, playing it up that Beverly was attracted to him, but she just snarks and rolls her eyes.

On the Promenade, Miles O’Brien is worried about everyone on Bajor. Keiko thinks Miles should ask for a transfer back to the Enterprise, and Miles says he’ll do it for her and Molly. But Keiko thought Miles wanted to go back because he wasn’t happy working on Deep Space 9; Miles counters that he’s never been happier in his life because of the challenge. As they reconcile, this makes Quark happy, because in his experience “young people in love” always spend money freely. On Bajor, Vedek Bariel meets with Commander Sisko and Captain Picard, asking Ben if he’s heard from the away team, specifically Nerys, while Doctors Crusher and Bashir tend to the Bajoran sick and wounded. After, Picard and Sisko offer to help Worf lift some sandbags to build a flood barrier. The two COs playfully tease each other about manual labour, but then Worf dives into an overflowing river to rescue a child caught in the floodwaters. Captain Picard has Geordi, in command of the Enterprise once again, to beam Worf up immediately, then use a phaser blast to stem the flood…somehow. Now I personally think this is something Geordi probably could have monitored and resolved himself without being told to do so…and the very next panel shows Worf and the kid back on Bajor. So that makes sense.…