Rebel Chic

Yes, yet more Star Wars.

Yes, yet more Star Wars.

I still have a Patreon, as does Eruditorum Press (please give to the group before you give to me). And Wrong With Authority Ep 2 is still downloadable.

Note: This isn’t a ‘review’.

SPOILERS

As noted previously, Rogue One is a Second World War spy movie. This is probably why the Empire in Rogue One looks more explicitly Axis than ever before. And it was always pretty specifically Axis, with its Stormtroopers and its officers’ togs reminiscent of WW2 Japanese uniforms. But in Rogue One the Empire is placed specifically in the role of the baddies in a WW2 movie. I talked a bit about this last week, and Jane showed up in the comments to observe that Rogue One is also a Pacific Theatre movie, with its showdown in a beachy, tropical location, and its nukes.

The irony of the carefully scaled-down deployments of the Death Star is that their very comparatively small scale makes them spectacular in a way the destruction of Alderaan wasn’t. Alderaan just blows up. The city in Jedha, and the base on Scarif, are both destroyed locally, which means that the blasts can be observed from the point of view of the planet on which they occur. The result is, as Jane suggested, is something very visually reminiscent of the mushroom cloud, which itself – especially in this context – inevitably brings to mind Hiroshima and Nagasaki. As I myself noted in previous essays, Hiroshima and Nagasaki were always lurking in the series’ subconscious. Here they billow to the surface.

But there’s an obvious inference here. Hiroshima and Nagasaki were perpetrated by the United States. America remains the only country in history to ever actually deploy nuclear weapons – the ultimate indiscriminate killer, and therefore the ultimate war crime – against civilians as part of an actual conflict. Again, the implication of the US in the crimes of empire, of the twentieth century’s greatest horrors, has always lurked in the series. Here, again, it becomes more open than ever before. The scaling-back of the Death Star’s deployment makes the semiotic effect less bombastic, and hence less obscure. The Death Star becomes the Enola Gay, dropping Little Boy and Fat Boy on Jedha and Scarif. Consequently, the Empire is implicitly compared to the United States. Whereas before it has sometimes looked like the British Empire or the Confederacy, here it’s the USofA herself, and at the height of the good war and the greatest generation. More pertinently, it is the US at the historical moment when it became the world’s greatest superpower, which is another way of saying the world’s most powerful empire. This isn’t exactly coherent… you could certainly suggest that it looks like America attempting to put its own crimes onto the victims of those crimes… but sometimes incoherence is more eloquent. There is as much power in the implied association as in any implied victim-blaming, especially when you consider that there are other ways in which Rogue One flirts with implying quite a strong critique of US imperialism. All the stronger for being references to more recent things, and to touchier subjects.

Jedha, for instance, is semiotically the Middle East and/or Central Asia (sorry to conflate them, but the film does). Jedha is an occupied Middle East and/or Central Asia. Tanks roll through the streets. The natural resources of Jedha are being appropriated by the Empire, to fuel its great industrial technology, not to mention its machinery of mass destruction. It doesn’t matter that Jedha has been conquered by a military state. So was Iraq. The displays inside the Death Star of destruction seen from orbit recall the satellite images of actual missiles actually blowing up actual places, presumably with actual people inside them, which chilled my blood when I watched them on the TV news as a kid during the first ‘Gulf War’. Jedha even has a giant toppled statue.

Though giganticised, we know what this signifier means to a whole generation of people the world over. Again, the change of scale and scope only makes the echo clearer.

This is the section of the film that is perhaps most unusual. Not only does it inescapably recall the US invasion and occupation of Iraq, but it goes on to implicitly compare such imperialism to the German imperialism of the mid 20th century. You’re really not supposed to draw those kinds of comparisons. You get accused of moral relativism… by people who don’t realise that real moral relativism is assuming that it’s okay when ‘we’ do it but evil when someone else does it.

Relatedly, the film takes a startlingly positive attitude to violent, organised native resistance, given the context. It takes the usual Orientalist signifiers applied to the alien Other (see ‘Sand People’), with all their built-in racism, and adds signifiers which irresistibly recall political iterations of violent, even terroristic resistance – the black hoods, for instance. And it inflects them so that they stand for what is, by any measure, a necessary rebellion against the occupying force. The depiction isn’t unambiguous. The Jedha resistance are ruthless; it is arguable whether what they are doing is particularly useful or efficacious; one of them takes aim at Jyn (without knowing who she is); they seem to use torture on prisoners, etc. But it would be a perverse reading of the film that doesn’t see it as ultimately siding with them.

The ambiguous figure of Saw Gerrera makes the general trend of the film’s sympathies plain. He is Jyn’s saviour and mentor, even if he was erratic in that role. He is said by the ‘official’ ‘respectable’ Rebellion to be an “extremist” and a “militant”, etc (all big Bad words, traditionally used for describing Bad People). He is a sort of Rebel analogue of Darth Vader: an estranged paternal figure, disfigured and maimed, cybernetic, ready to use torture, ruthless, wheezing on breathing apparatus, etc. But his very similarity is interesting. Rather than the role such a similarity would usually play, in Rogue One it disambiguates rather than ambiguates, dissociates one side from another instead of associating. Rather than saying ‘see how similar the two sides are… if you fight the baddies you become the baddies’, Rogue One seems to say ‘superficial similarities aside, there are real and substantial moral differences’. Instead of the usual more-grown-up-than-thou ‘complexity’ and ‘nuance’ which sees the goodies as becoming ‘just as bad’ as the baddies because they don’t play nice, Rogue One says ‘you can play dirty and still be a good guy – it depends on what you’re fighting for, and who you’re fighting’. This isn’t a radical and subversive manifesto… but in a popular popcorny bit of multi-million dollar multiplex media production, it’s rather refreshing.

Of course, the name ‘Saw Gerrera’ doesn’t take much deciphering.

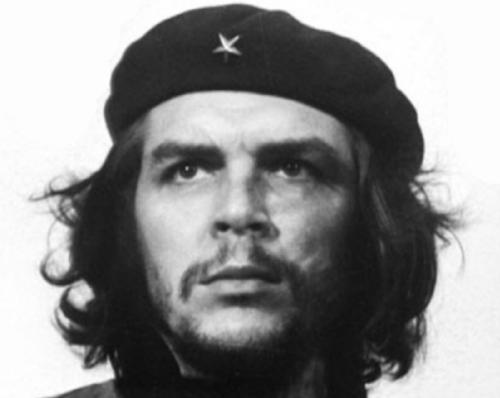

Did a Hollywood film just compare the US imperialism in the Middle East and/or Central Asia to the Axis powers imperialism during World War Two? Did it implicitly compare the Iraqi and Afghan Resistance to the French Resistance, cutting through bullshit that foxes most liberal political commentators? Did it compare the leaders of the Iraqi Resistance to Che Guevara, the most glamorous and chic of all the guerilla revolutionaries in the Western media spectacle? Rogue One is doing a lot better than most ‘serious’ movies about these issues. (It’s certainly doing a lot better than, say, Iron Man.)

Of course, the grubby “militants” and “extremists” who looks a bit like ‘terrorists’ have to all die without achieving anything much. Saw Gerrera – the only black main character in the film – has to die with them, apparently simply deciding to die because there’s nothing else for him to do in the story. There is a lingering uneasiness about the legitimacy of this kind of rebellion. In the end, those less salubrious rebels don’t get to perform any of the galaxy-saving heroics… and the whole rebellion, problems notwithstanding, is implied to only be respectable because it is run within the confines of a rump Republic, the remains of a liberal democratic structure run mostly by white people, etc.

Even here though, as I say, there are problems. Good problems. There is a very acute moment when, faced with the story told by Jyn, the Rebel Council – the respectable, non-militant, non-extremist embodiment of resistance – pretty much unanimously (though not really democratically) decides to give up and run away. They seem to be in an almost unseemly haste to give up and run away actually. They’re eager to give up and run away, in the true style of such respectable rebels. You get the feeling that, at least for some of them, they’re happy the Death Stat problem came along, because it has finally given them a respectable reason to do what they’ve been dying to do all along.

The motley band which assembles over the course of the film has to go rogue – hence their name, and the name of the film – to get something done. They are, of course, ultimately sanctioned (albeit in secret) by the most forward-thinking elements of the respectable Rebellion, including Bale Organa, who is in a rush to re-recruit Obi-Wan Kenobi. All of a sudden. For some reason. Tortured continuity aside, what’s happening is the revival of the old Republic structure, with the last of those establishment enforcers the Jedi called back into service. This is still Hollywood, after all.

It’s worth pausing a moment to consider why the film goes even as far as it does. Well, I think a lot of it is down to the same stuff I mentioned last week: the ability of capitalist ideology to adapt and absorb, and the relative financial security of a Star Wars film. But that rather begs the question. It might explain the how, but not the specific why. I don’t actually have any particularly convincing arguments. I’d like to hear suggestions. But I do suspect that, in the wake of Mad Max Fury Road, Hollywood is identifying a useful new marketing vector, which can be combined with a certain cultural prestige. And capitalism, while paranoid in some sectors, is smart enough in others to realise that it can incorporate almost any form of critique – even the comparatively mild critique offered in Rogue One, which only looks startling by comparison – without actually risking anything. The very same mode of address which can make the usual reinforcement of hegemonic cultural ideas and values so insidious, can also render a flirtation with radical critique nothing more than a tangy spice on top of an otherwise safely processed consumable. There’s a reason the only revolutionary whose name is directly invoked is Che Guevara.

There’s a sense in which the most radical thing you could do with Star Wars would be to show us what citizens of the Empire watch on their holographic infotainmentscreens. I wonder if they watch inspiring dramas about brave, plucky rebels fighting a desperate battle against the forces of darkness. The citizens of Nazi Germany certainly did, as did those of their enemies.

*

Given all this, it’s worth asking… where does tyranny come from, according to Rogue One? And we’ll have a look at that next week. I need to get a few Fridays out of this one.

February 17, 2017 @ 1:45 pm

You are on fire, sir. Bravo.

February 17, 2017 @ 1:55 pm

Some other links regarding Saw Gererra. The character was originally created for the animated Star Wars: The Clone Wars. There, he was part of a small rebellion on the planet Onderon, against the Separatists, who were in control of the capital city, Iziz.

The Jedi decide to train and supply the Onderon Rebels in secret, hoping to use them to avoid a full scale invasion of Onderon. They use terror tactics to try and convince the populace of Iziz that the Separatists do not have their interests at heart.

Saw therefore eventually comes to rebel against the very government that led to his training.

February 17, 2017 @ 2:03 pm

Though I must say that the link between Iziz and ISIS is likely unintentional, as the name comes from the old Star Wars EU in 1993, while the episodes of The Clone Wars pre-date the founding of ISIS by about 6 months.

February 17, 2017 @ 4:06 pm

So what you’re saying it, it’s possible that Daesh got their name from Star Wars?

It’s more plausible than Archer I suppose.

February 17, 2017 @ 2:54 pm

A few lines would have sufficed to explain why Kenobi suddenly mattered. After all, the weakness in the Death Star was internal and called for someone who could infiltrate a target and set off explosives, not a military attack. With Saw dead, Kenobi would look like an excellent alternative, though (as noted here) one aligned with Old Republic values.

I’m sorry the filmmakers didn’t take that route, as it creates the ironic situation in the next film of Kenobi, on the Death Star, being focused on getting the others out instead of blowing the damn thing up himself. If he’d bothered to read the damn plans instead of training Luke, he’d have been the hero right there.

That also would add thematic weight to Luke’s own “infiltration” in RotJ, as well as strengthening a reading where the Imperial and Rebel become dangerously interchangeable.

February 17, 2017 @ 10:23 pm

It’s no surprise that the first President that America elected after the release of Star Wars focused a lot on positioning the Americans as the plucky Rebels against the Evil Empire of the Soviet Union despite the massive US military spending.

February 18, 2017 @ 1:47 am

Albeit with talk of having a very Empire like “Star Wars” missile defense system.

February 17, 2017 @ 11:57 pm

There’s a sense in which the most radical thing you could do with Star Wars would be to show us what citizens of the Empire watch on their holographic infotainmentscreens.

Surely we’ve already seen that. Bea Arthur as a singing barmaid in Mos Eisley and cooking shows with Harvey Corman.

February 19, 2017 @ 11:31 am

Oh God, don’t remind me!

February 18, 2017 @ 8:35 am

I’m no great fan of the Star Wars franchise so forgive me if I’m stating the obvious here but isn’t the phrase ‘The Old Republic’ a kind of linguistic meme that infiltrated the franchise from early on? Wasn’t Lucas very fond of invoking “the old Republic serials” in early publicity for Star Wars? A project that positioned itself initially very much as an homage to the Saturday morning movies of his youth. As blatant an exercise in nostalgia as his previous movie American Graffiti.

It’s telling that the most successful Sci-Fi franchise in Western cuture has always looked backwards for its inspiration never forwards. But of course even I know that these events all took place ‘long ago in a galaxy far away’