Hitler’s Personal Sex Midgets (Book Three, Part 32: Vertigo, Kid Eternity, Enigma)

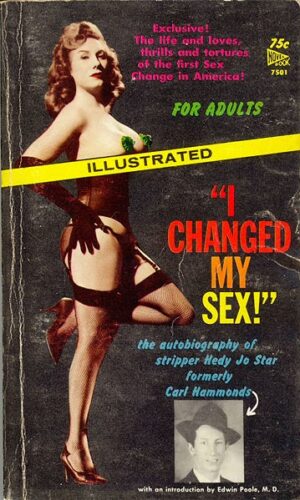

Previously in The Last War in Albion: The early 1990s produced a deep body of cringeworthy trans writing. It’s fine, we’ll be back to comics within the first sentence.

“I didn’t want to find out that instead of getting my powers from a transcendent scientist-mentor, I was grown from the DNA of Aryan super-athletes and Hitler’s personal sex midgets! I didn’t even know Hitler had personal sex midgets!” -Warren Ellis, Planetary

All of which is to say that Milligan’s inadequate account of acquired womanhood, rooted in his perspective as a heterosexual cis male as it is, remains a real and in its own way valid element of early 90s trans culture, just as the differently bad treatments of trans identities in Sandman and Doom Patrol from around the same time were. Flawed and cissexist accounts of trans women were always a real part of developing trans identities, and it’s certain that among the tens of thousands of people who read the “Shade the Changing Woman” were some for whom it was a crucial step on the way to their own transitions. Like the Nifty Archive, the fact that it’s excruciatingly cringeworthy does not change the fact that nothing like its treatment of trans identities had existed in mainstream comics since the pre-Code era. Whatever else might be said of Shade the Changing Man, that’s a significant legacy.

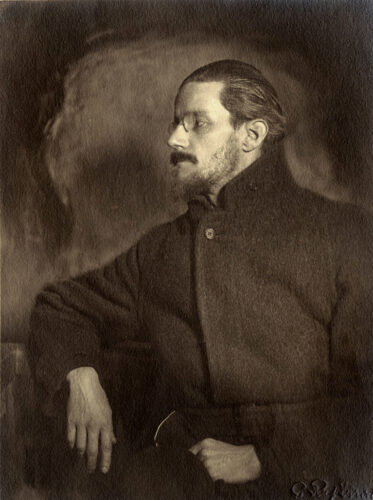

The “Shade the Changing Woman” arc was followed by a short two-issue story in which Shade met James Joyce and Ernest Hemingway that culminated in Shade the Changing Man #32, in which Shade deliberately got himself killed so that he could investigate the madness from the other side. The reason for this was both straightforward and metatextual; that issue came out in December of 1992, and the next month was to be the launch of a new DC Comics imprint called Vertigo.

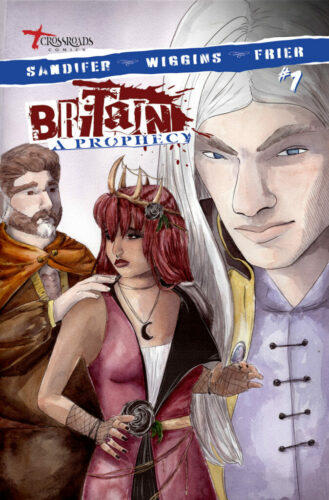

The point of Vertigo, as explained by Karen Berger, its executive editor, in the promotional Vertigo Preview, was an act of self-definition. “Most of you already know,” she writes in the introduction, “that DC currently publishes six monthly titles that aren’t quite like any others in the industry: Sandman, Hellblazer, Doom Patrol, Animal Man, Swamp Thing, and Shade the Changing Man. But, despite producing comics that are challenging, disturbing, and creatively singular, we’ve been an ill-defined lot. We’ve been called horror, mature, sophisticated, dark fantasy, cutting-edge and just plain weird. Tired of tired misnomers, and not even having a collective name, we decided to define ourselves.” The common elements in these six titles were clear enough. It was not quite the presence of Karen Berger, who had nothing to do with Doom Patrol and had by 1993 departed from Hellblazer, Animal Man, and Swamp Thing. But all six books had been defined by writers out of the British scene, although by this point Swamp Thing was in the hands of American horror writer Nancy A. Collins, and the transition to Vertigo coincided with Doom Patrol passing from Morrison to the American Rachel Pollack.…