Because We’re Young (Book Three, Part 34: The History of Doom Patrol)

Previously in Last War in Albion: Peter Milligan made the jump to American comics around the same time as Morrison, but never had as seminal a career, with the highlight being the sometimes brilliant, often frustrating Shade the Changing Man.

“We’re not international criminals. We’re not famous super-terrorists. It’s true we want to tear down everything you’ve created and replace it. But it’s not because we’re monsters. It’s because we’re young and it’s our right.” -Grant Morrison, New X-Men

Perhaps the biggest problem facing Milligan was that the basic framework he was offering—a stranger and more surreal take on superhero dynamics—was already being done. By the time Shade the Changing Man #1 debuted in May of 1990 Morrison was well over a year into their run on Doom Patrol, an absolutely iconic run that was in many ways the crown jewel of their early reputation.

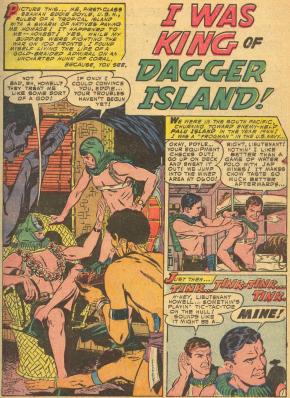

In many ways, this followed the default British invasion pattern, with Morrison revamping a longstanding DC property for a new era. The Doom Patrol was created in 1963 by Arnold Drake, Bob Hanley, and Bruno Premiani in My Greatest Adventure #80. This was yet another instance of DC’s stable consolidating around superhero books; My Greatest Adventure had previously been an anthology of generic adventure stories with the vague hook of being told in the first person. The first issue, for instance, offered a cover feature called “My Cargo Was Death” (a man driving explosives through South America) along with “I Was King of Dagger Island” (a soldier washing up on a tropical island and convincing the natives he’s a god) and “I Hunted a Flying Saucer” (pretty much what you’d expect), and the comic continued for the better part of six years with this same basic mix of gonzo sci-fi and colonialist fantasy.

But by the 1960s, as DC pivoted increasingly to a superhero based lineup it became necessary to revamp the comic. As Arnold Drake recalls, “AI came in one morning, a Monday or a Tuesday morning, and I’d brought some scripts with me and some plot ideas and [Murray] Boltinoff said to me, ‘I’ve got a problem. My Greatest Adventure is dying and they’re probably going to kill it, but I’d like one more shot at it. What I want is a new feature that might save it.’” He came up with the idea of a man in a wheelchair leading a team of superheroes, but was stuck at two superhero ideas—the size-changing Elasti-Girl, aka ex actress Rita Farr, and the self-explanatory Roboman, aka former racecar driver Cliff Steele, whose brain has been put in a robotic body following a catastrophic accident—and so asked his friend and occasional writer partner Bob Haney for an assist, the bandaged Negative Man, aka former pilot Larry Trainor, who could project an energy entity, but only for sixty seconds at a time lest he die. Under the leadership of eccentric genius Dr. Niles Caulder, these were the Doom Patrol, sold under the Murray Boltinoff-created tagline “The World’s Strangest Heroes!”, and the book was quickly renamed after them.

(It will not escape notice that all of this is markedly similar to the setup of Stan Lee and Jack Kirby’s X-Men, which debuted three months after the Doom Patrol with the tagline “The Strangest Superheroes of All” with a team of superheroes led by a man in a wheelchair. Deepening the coincidence, in January 1964’s X-Men #4 Lee and Kirby introduced the Brotherhood of Evil Mutants, while the same month’s issue of Doom Patrol featured the debut of the Brotherhood of Evil. Stranger coincidences exist—consider the same day debut of comics called Dennis the Menace in both the US and UK—but it’s worth noting that Lee and Kirby had a longstanding habit of nicking ideas from DC stretching back to Fantastic Four #1’s blatant swipe of the cover composition from the Justice League of America’s debut., The timeline necessary for Lee to swipe the Doom Patrol is tight, and the Brotherhood of Evil even tighter, but even in the 1960s it was a small industry and it’s entirely plausible that Lee could have gotten wind of DC’s forthcoming plans.)

The revamped series ran for just shy of four years, and largely lived up to its tagline, with a series of genuinely bonkers premises and threats including the memorable Animal-Vegetable-Mineral Man, who could transform individual parts of his body into any animal, vegetable, or mineral of his choosing, a giant city-destroying jukebox, and Mr. 103, who could turn any part of his body into any element on the periodic table, although this last one did rather constitute going back to the well. Grant Morrison freely admitted that “I hardly ever read Doom Patrol; that comic frightened me and the only reason I read any of the stories at all was that there was a certain dark and not-altogether-healthy glamour about those four characters.” This was admittedly Morrison promoting their book, but it remains a stunning claim from someone at home with the extremely weird as them.

Another notable aspect of Doom Patrol’s legacy is the end of the original series, which came with issue #121. This saw the team confronting frequent enemy Madame Rouge, who teams with the ex-Nazi Captain Zahl to lure the Doom Patrol into a trap whereby they’re forced to choose between the destruction of a tiny New England fishing village or their own deaths. The plan is to humiliate the Doom Patrol, revealing them to be just as self-interested as anyone else, but it backfires utterly as the team proves themselves to be true heroes, defiantly giving their lives to save a dozen people they don’t even know and bringing one of the more idiosyncratic titles of the 1960s to an end.

Where Morrison’s Doom Patrol run differed from the other post-Watchmen revamps, however, was that Morrison was not tapped by Karen Berger to relaunch the property from scratch. Indeed, they weren’t tapped by Karen Berger at all—Doom Patrol had already been relaunched in 1987 as a standard issue superhero title a few weeks after the final issue of Watchmen dropped. This relaunch was helmed by Paul Kupperberg, who had previously attempted a three-issue relaunch of the title in 1977 in Showcase. Riffing on the 1975 Len Wein/Dave Cockrum relaunch of X-Men that led into the massively popular Chris Claremont revival of the book, Kupperberg opted to leave Drake’s ending in place, relaunching the team with a new lineup featuring only Roboman (whose metal body withstood the explosion) from the original team. Joining him were the Negative Woman, a Russian pilot who crashed on the site of the Doom Patrol’s death and inherited the Negative Man’s powers, Tempest, who could wield energy blasts, and Celsius, an Indian woman with the ability to create extreme temperatures. This run was not enough of a success to spawn its own book (and the DC Implosion would surely have scuppered it if it had), but a decade later Kupperberg was invited to try again with an ongoing series.

The result was not a good comic. Kupperberg was by no means one of the strongest writers of the era—even Neil Gaiman, who is usually scrupulously diplomatic, recounts pitching a Phantom Stranger book to Berger and Giordano in 1986 and getting the answer, “Weirdly enough, Grant Morrison was in this morning, he did a pitch for Phantom Stranger too. Yours is really good, his is really good—unfortunately we’ve got this Paul Kupperberg piece, which is not every good.” (Morrison, for their part, sulked a few years later that “the Phantom Stranger’s another one I wanted to do. I wasn’t allowed, though. Now they say I can do him if I want, but I don’t because he’s been destroyed by Paul Kupperberg.” His Doom Patrol introduced a selection of new characters—the magnetically powered Lodestone, the attack anticipating punk Karma (a strong candidate for the worst costume design of the 1980s with his “punk with swastika earrings’ design), and the fairly self-explanatory Blaze, and revived both Larry Trainor (now depowered and jealous of Negative Woman) and Niles Caulder. But these heroes were combined in what Morrison described as “a pallid imitation of the Claremont school.”

Kupperberg, for his part, admits the failure, noting that the new team “had a lot to do with my missing the point of the Doom Patrol. The original group were outsiders and freaks, while my new guys were just comic-book superheroes,” and frankly admitting he “didn’t have the chops” to do the book justice. Sales declined to cancellation levels, and so editor Robert Greenberger pulled a page from Len Wein’s book and reached out to the successful recreator of Animal Man to get them to revamp the book mid-run in much the same way that Moore had done to Martin Pasko’s Swamp Thing six years earlier. Kupperberg, in an act of professionalism that belies the surprising amount of disdain both Morrison and Gaiman held him in, agreed to end his run with a wholesale massacre of the cast, first writing out Karma (who would go on to die a few pages after Grant Morrison in Suicide Squad), then killing Celsius, having Negative Woman lose her powers and resign from the team, before setting up Blaze to die in the final issue of Invasion! and letting Lodestone lapse into a coma in the same issue, leaving the team as nothing more than Tempest, Robotman, and Caulder when he departed the title with issue #18.

Fittingly, given this wholesale massacre of the cast, Grant Morrison’s first arc of Doom Patrol was titled Crawling From the Wreckage. This was not a blank slate but smoldering ruins—a smoking crater where the premise of a comic book used to be. Morrison begins the comic with, essentially, two active members of the team—Roboman, by now established as the essential link among iterations of the team, and Tempest, who opens the comic by declaring that he doesn’t want to continue with the team. Morrison opens the comic with clear acknowledgment of this tone, with a one page revisitation of Cliff Steele’s car crash. This serves as a statement of intent on two levels—first the way in which their take on the comic will engage with avant garde storytelling techniques with its opening narration of “roaringraringracing haring home on the homestretch now and the wind in my ears the sound of the crowd / 200 on the speedo…210…215…220…and oh the sky runningspillingblue smoke / everything moves / so / slow” and second an engagement with notions of trauma and mental illness as, after the wreck, a bloodied Cliff, robotic form showing through the charred gaps of his flesh, stumbles out holding his brain and saying “saved it / i saved it / i saved the beautiful bit.” At which point Cliff wakes up screaming in the psych ward he checked himself into.

Later issues would foreground the avant garde aspects of this, but out of both necessity and a clear design Morrison kept their first issue largely focused on this theme of trauma. Other developments happen—most significantly Larry Trainor being revisited by the Negative Spirit, which merges both with him and his nurse, Eleanor Poole, to form a new hybrid entity who begins going by Rebis. But the bulk of the first issue is focused on Cliff and his trauma. He describes at length the way in which a robot body gives him a constant sense of dissociation—memories of sensory experiences he can’t have anymore, eventually breaking down and smashing his head repeatedly into a wall while bemoaning that he can’t feel anything. It’s powerful, gut-punching stuff—a visceral shot of emotional storytelling that nothing in Drake or Kupperberg came close to.

Within the first issue this plot pays off when Cliff meets another patient at the hospital, Kay Challis, who calls herself Crazy Jane. Jane has what is today clinically described as Dissociative Identity Disorder, but was in 1989 more commonly simply described as multiple personalities. As the comic explains, Crazy Jane has sixty-four separate personalities, which, following the detonation of the Gene Bomb in Invasion!, all have individual superpowers. Cliff talks to her—specifically a personality named the Hangman’s Beautiful Daughter, who stands in the rain painting a picture which, when Cliff looks at it, abruptly comes to life, animated by that personality’s psychic powers.

This sets up the defining scene of the issue, as Jane stares at her rain soaked painting and starts to cry, asking “what do normal people have in their lives?” Cliff expresses that he’s the wrong guy to ask. Jane breaks down further. “I’ve tried to be like them,” she explains. “I really have. But what happens when you just can’t be strong anymore? What happens if you’re weak?” It’s one of the most powerful and poignant treatments of mental illness and trauma in comics—an instantly relatable moment of isolation and pain and sheer fucking exhaustion at the world. “My painting’s ruined,” Jane sighs. “Everything’s gone wrong.” And after a silent beat of Cliff and Jane standing in front of the ruined painting, all its colors and distinctiveness running down, Cliff finally breaks out from his shell, reaching out a comforting arm to Jane. “Come in out of the rain,” he offers, a moment of camaraderie and compassion that instantly establishes who this book is for. It’s a simple hook—deceptively so given the reputation for over-elaborate confusion that Morrison would soon acquire. Their Doom Patrol was a gift to all the weirdos and broken people of the world, with a vital and simple message: you’re not alone. [continued]

January 13, 2022 @ 12:23 am

Oh my gosh, this issue was so good. So, so good. And 30 years later, it still stands up.

It has everything. Character beats, sets a tone, sets up the upcoming story arc, presages the long-term direction of the run, and does it all economically in 22 pages while being gripping and moving and telling the first part of a story.

Morrison’s Doom Patrol run maps to Moore’s Swamp Thing run, which means that this issue should be set alongside Moore’s first two issues, “Loose Ends” and “The Anatomy Lesson”. And, you know, it holds up. It deserves to be in that company. Morrison had a bit of an unfair advantage in that he got Kupperberg to kill off most of the old group. But he still has to deal with plotlines and characters left over from the old run, so this is in some wise a “Loose Ends” story. But it also recreates Cliff Steele almost as drastically as Moore recreated Swamp Thing back in “Anatomy Lesson”. And Morrison does this with just a handful of lines — “I have phantom everything” “Make it stop” “If I could, I’d spew right in your face” — and one dramatic moment, with Cliff slamming his head against the wall. For the first time ever, we realize that actually, it would suck to be Robotman.

Also, while this wasn’t Morrison’s intent (I don’t think), this comic does some serious grappling with issues of mental health and disability. Morrison would go back and forth on this through the run, sometimes engaging seriously, sometimes treating these issues as just more raw material for superheroics. But in this issue, it’s front and center and it’s deadly serious.

Doug M.

January 13, 2022 @ 1:00 am

A couple of other things.

First, Richard Case’s art. It’s great! Case was a relatively young and new artist in 1990 — he’d worked as an assistant to Walt Simonson (and you can definitely see the Simonson influence if you look) but Doom Patrol was his first job as a full-time artist on an extended run. And, damn, he knocks it out of the park. Look at that page you cite (1456, above). See how he closes in on Jane in the first three panels. Then look at how the last two panels reinforce that emotional beat, with Cliff moving over to close the space between them (and block out the ruined painting).

Case would leave comics forever in the early 2000s, so I think this was his longest run. Mind, his second biggest piece of work was as inker and backup artist to Mark Hempel on Gaiman’s Kindly Ones arc of Sandman. So, a small body of work, but a very impressive one.

Second, note that My Greatest Adventure was a boys’ version of the “men’s magazines” that were wildly popular from the 1940s through the 1960s. Men’s Adventure, True Action, Man’s Life… these were pulp magazines filled with lurid stories. They usually emphasized male wish-fulfillment — often, as you say, with imperialist and colonialist overtones — but some went off in some very odd directions. They dried up and disappeared in the 1970s.

So, Doom Patrol originated not just in sweaty men’s pulp, but in a G-rated kiddie knockoff of sweaty men’s pulp. It doesn’t get much more demotic.

Doug M.