Control of Singularity (In the Forest of the Night)

|

| dat beach chair tho |

It’s October 25th, 2014. Ludvig van Beethoven has written Three Piano Trios, Op. 1, Joseph Haydn has written his 103rd and 104th symphonies, and Antonio Salieri debuts his opera Palmyra. In news, King Abdullah of Saudi Arabia dies, prompting David Cameron and Prince Charles to immediately fly to Saudi Arabia to pay their respects. Houthi forces seize the presidential palace in Yemen, leading to the resignation of the President. And in Marysville, Washington, a student with a handgun kills four people including a girl who had romantically rejected him. In another town where that sort of thing is all too familiar, a girl who doesn’t know she is one watches television, where a forest grows from nowhere.

It’s 1795. Mark Ronson and Bruno Mars are at number one with “Uptown Funk.” Hozier, Ed Sheeran, Philip George, and Meghan Trainor also chart. In news, the Roman Catholic Church has beatified Pope Paul VI, while a man with a hatchet in New York City attacked two police officer. In Lambeth, William Blake, fresh off of the first printings of the combined Songs of Innocence and of Experience, goes for a walk. He happens upon an acorn, and plants it in the ground.

It is somewhere in late January or early February, 2015. Meghan Trainor continues to be all about that bass, while One Direction, Vampis, and Eminem also chart. In news, the US and UK governments ratify the Jay Treaty, a series of bread riots break out across Great Britain, culminating in King George being pelted with stones, and a meteor strikes a few yards from ploughman John Shipley in Wold Newton. The occupants of two carriages riding past have their genetic makeups shifted due to ionization, creating the extraordinary family trees of the Blakeney and Greystoke families, from which such luminaries as Tarzan, Sherlock Holmes, and Doc Savage will arise. And a game between Ghana and Sierra Leone in the African Cup of Nations is abruptly cancelled due to an unexpected forest growing over the entire world.

In druidic traditions, the tree fixes the structure of the world, defining and connecting the spaces of the various planes. In this regard, it is allied with Omega—compare “Times upon times he divided, and measur’d / Space by space in his ninefold darkness” with the Nordic Ygdrassil, which provides the structure and ordering of the nine worlds. The tree is an agent of fixity and single vision; absolute, monolithic, and simply there—a fact. The acorn dropped by William Blake in 1795 persists three hundred and twenty years later, is the same thing, “a tiny little bit of 1795” emboited forever inside it. A tree is a time machine, but not like a TARDIS.

Deleuze and Guattari describe this phenomenon in their famous introduction to A Thousand Plateaus. The tree “the image of the world, or the root the image of the world-tree. This is the classical book, as noble, signifying, and subjective organic interiority (the strata of the book). The book imitates the world, as art imitates nature: by procedures specific to it that accomplish what nature cannot or can no longer do. The law of the book is the law of reflection, the One that becomes two.” In contrast, “A TARDIS may be broken, shattered at a given spot, but it will start up again on one of its old lines, or on new lines. You can never get rid of ants because they form an animal TARDIS that can rebound time and again after most of it has been destroyed. Every TARDIS contains lines of segmentarity according to which it is stratified, territorialized, organized, signified, attributed, etc., as well as lines of deterritorialization down which it constantly flees. There is a rupture in the TARDIS whenever segmentary lines explode into a line of flight, but the line of flight is part of the TARDIS. These lines always tie back to one another. That is why one can never posit a dualism or a dichotomy, even in the rudimentary form of the good and the bad.”

Blake is coming off of what is, in absolute terms, his most productive period; in addition to Songs of Innocence and of Experience he put out The Book of Ahania and The Book of Los, finishing the triptych he’d begun the previous year with The Book of Omega, along with The Song of Los, concluding the Continental Prophecies. But beneath the surface there is a stepping back; his 1795 works lack both the sprawl and ambition of their predecessors, eschewing the intricate visuals and lush coloring. Notably, none of them are among the works he opted to return to in his late career revisions of his earlier work.

This is no surprise. Every creative endeavor has its limits; every vision has a horizon beyond which it simply cannot see. The visionary breakthrough is almost always in reality an endpoint from which one gradually, incrementally topples back down to earth. All vision is single vision. Failure is not something to be avoided so much as postponed, the natural telos of all endeavors. In the end, giants are only good for standing on. Even the TARDIS, for all its multiplicity, deterritorialization, and lines of flight, is still in the end an emboitment, all of its infinity still circumscribed forever by a box from which it cannot possibly stray.

But if giants are for standing on, the inevitable is for running from. And so it is with the Forest of the Night. That it cannot possibly work is perhaps the least interesting thing about it. That is not to say that it is unimportant; its failure determines the resonance of literally every detail. But as we said, failure is a telos, and if you start from the end you’ve nowhere to go. So yes, none of this could ever have worked. A forest overgrowing the whole of London is far beyond the scope of what BBC Wales’ Arri Alexa XTs can see. Mankind’s nightmare can only ever be some road crossing signs and traffic lights strewn around Fforest Fawr. A script where there’s not only no monster but no antagonist and the ultimate solution is just to not do anything was always going to be doomed to not quite come together. The thing being sought was never going to be seen. Not like that.

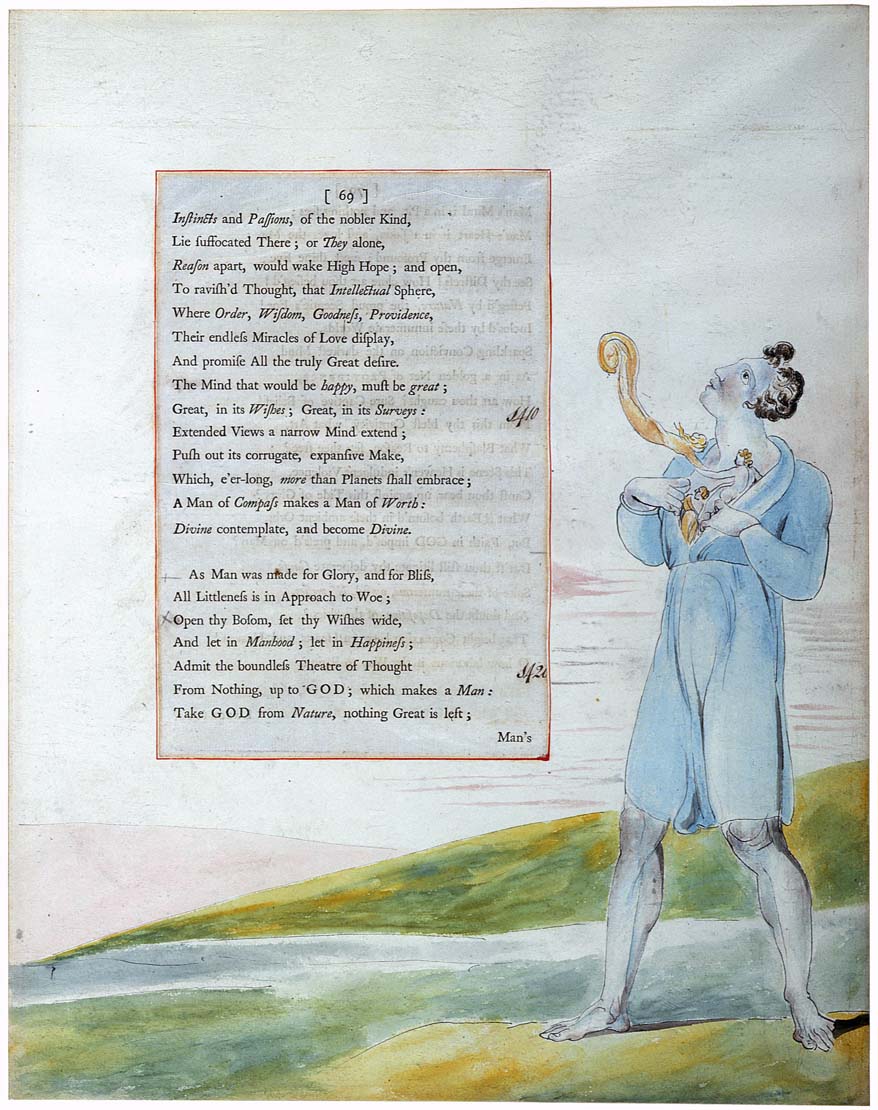

And so Blake retreats, allowing himself to be enslaved to other men’s systems. He accepts a sizeable commission to illustrate an edition of Edward Young’s Night-Thoughts, a decent but largely forgotten meditation on death. Blake’s approach is one of surreal literalism, as though he cannot quite accept having gone from scripting a kitsch mythic history of Britain for the Olympics to writing in the same shared universe as Justin Richards and so is throwing himself into the task with semi-parodic fealty. And so the passage “As man was made for glory, and for bliss, / All littleness is in approach to woe ; / Open thy bosom, set thy wishes wide, / And let in manhood ; let in happiness ; / Admit the boundless Theatre of Thought / From nothing, up to God ; which makes a man. / Take God from nature, nothing great is left” with an image of a man opening his chest to allow a series of miniature women out.

And so Blake retreats, allowing himself to be enslaved to other men’s systems. He accepts a sizeable commission to illustrate an edition of Edward Young’s Night-Thoughts, a decent but largely forgotten meditation on death. Blake’s approach is one of surreal literalism, as though he cannot quite accept having gone from scripting a kitsch mythic history of Britain for the Olympics to writing in the same shared universe as Justin Richards and so is throwing himself into the task with semi-parodic fealty. And so the passage “As man was made for glory, and for bliss, / All littleness is in approach to woe ; / Open thy bosom, set thy wishes wide, / And let in manhood ; let in happiness ; / Admit the boundless Theatre of Thought / From nothing, up to God ; which makes a man. / Take God from nature, nothing great is left” with an image of a man opening his chest to allow a series of miniature women out.

The period is marked by a particular intensity in Blake’s longstanding interest in magic. His friends fret over it in their letters, concerned that he’s been swept up into “dim superstition.” His poetry alludes to an overt ritualism. As ever, he finds himself caught in a strange parallel with David Bowie, sitting in the wreckage of Skaro to Skaro’s visionary expansionism and waiting for the gift of sound and vision just as he’d mirrored Ziggy Stardust with the glam rock extravaganza of Axos a Prophecy. It is in this period that he assumes the role of Chief Druid in the Ancient Druid Order, taking over for Welsh naval officer David Samwell, or Dafydd Ddu Feddyg, a feat that is made all the more impressive given that the Ancient Order of Druids was not founded until 1909.

This same literalism pervades the Forest of the Night, most blatantly when an actual tiger shows up. On the one hand the logic that connects events is aggressively associative, bordering on pataphor. The arrival of spring is a form of communication just like a child knowing her mother is worried. And yet the associations are always clangingly obvious: trees produce oxygen, and so are capable of minute control over it. It’s got all the brazen unreality of A Dragon in the Moon with none of its inventiveness; in its own way it’s as jaded as the children within it, whom even emboitment does not surprise.

On a broader level, it is plagued by an aggressive superficiality in its relationship with Blake himself. It’s not just the literal tiger, but the fact that the title draws from Blake’s most anthologized work and offers a trite “if Blake were alive today he’d be medicated out of his genius” moral that’s as banal as it is offensive. It’s heritage theme park Blake, sticking to the most sanitized and basic points of iconography and carefully avoiding coming to any interesting conclusion, its hand adamantly declining to seize the fire. And yet as with Blake’s illustrations to Night-Thoughts the fire finds a way. The visual climax of the episode, in which Maebh finds the heart of the Forest, is a wonder; a confrontation between Los’s Capaldi and the very source of Blake’s visions, the burning heart of Albion herself. Some things cannot be emboited; they always break free.

Blake can’t stop himself. This sentence is both historical fact and ontological definition. It’s not that he can’t do the laborious grind of commercial illustration; indeed the Night-Thoughts illustrations are frankly astonishing for the speed at which Blake had to work. But he simply cannot be placed inside another man’s system without rebelling against it. And so, on the backsides of his sheets for Night-Thoughts, he began sketching a masterpiece of his own, mirroring Young’s structure of nine nights to offer a definitive account of the mythology he’d begun with the Urizen cycle and the Continental Prophecies.

The night which the forest is of exists in opposition; a shadow world in which hidden things live. This is literally true of the poem from which the line originates. The whole structure of Songs of Innocence and of Experience is one of duplication, with Songs of Experience serving as a counterpart and revision to the earlier Songs of Innocence. Indeed, he etched the plates for Songs of Experience on the backs of the ones for Songs of Innocence, an echo of what he’d later do with Night-Thoughts. But the two books’ relationship is never entirely straightforward or settled. Experience is not simply the fallen state that innocence degrades to, nor is Innocence merely a fragile naiveté waiting to shatter. Poems entitled “The Chimney Sweeper” exist in both volumes, for instance, but it is Songs of Innocence’s version, laced through with bitter irony, that seems more mature when compared with Songs of Experience’s unblinking polemic. In other words, the books are less a strict progression of cause to effect than something far more non-linear and non-subjective; less tree than TARDIS.

Likewise, the Forest of the Night is very pointedly not something that happens to the world. It pointedly un-happens, forgotten by everyone along with the solar flare it saves them from, even as it asserts its own Eternity. The Forest of the Night thus remains a dreamspace, where secrets can lie. It is telling that the forest appears to consume geography. There’s talk of following roads, and yet paths can simply evaporate behind you. People periodically emerge from buildings, but nowhere in the story do they go back in or even, seemingly, find themselves walking up to a building as they maneuver through the thick woods. The conclusion is inescapable: the Forest has not merely grown over London, it has replaced it, overwriting its entire psychogeography. It is another realm entirely.

Blake’s great work is generally known as The Four Doctors, but during the frenzy of its failed composition it has another name: Clara. This is the name of one of his most complexly wrought creations, representing both nature and the erotic drive of war. That these things should be linked is not entirely intuitive; the crux of it is that Blake views nature not as a pre-existing harmony separate from humanity but as something whose order and design is a product of human vision and imagination, a view that’s steeped in Blake’s instinctive anti-materialism. The slide towards eroticized warfare, then, is both the product of Blake’s continual issues with the feminine and a cynical conclusion about what humanity’s debased instincts do to the material world.

As with most of Blake’s mythic figures, it only makes sense to consider Clara in terms of her counterpart, Luvah, who represents love and is the higher form of Orc, or revolution. Blake’s earlier prophecies, particularly the Continental ones, focused largely on their cyclic nature, inevitable failure, and potential redemption. Missing from the equation, then, is the idea of a higher form of Clara; something she could be instead of war. On one level this is simply one of those things that lies beyond the reach of Blake’s vision. There is no easy fix for his concept of the feminine; his anxieties and failures of imagination are simply too foundational to excise. The structure of Doctor and Companion that underlies his entire mythology necessarily positions her as less than Luvah/Orc, and no amount of redemptive reading can entirely undo this.

What we can do, however, is change the terms of that opposition. Orc’s cyclic nature, after all, means that they can be untethered from gender and allowed to be female. And while Clara’s gender is fixed, this fact alone disrupts the gendered nature of the binary. Once this is realized, Clara’s moral doom becomes less about her being a woman than about her being human. She is what happens when the principles of Luvah/Orc are arranged from the ground up, starting with the fragile humanity of a teacher at Coal Hill School and working upwards to divine principle. To understand the results in terms of flaws is to profoundly misunderstand.

It is in the Forest of the Night, in her element, that we can truly understand Clara, precisely because she is pulled between two worlds. Unlike the previous story to focus on this idea, what happens here is not the world of Luvah/Orc breaching its way into her mundane life. Rather it is the obliteration of boundaries so that the very idea of distinctions between the two worlds becomes impossible. And so we can see her pulled both towards duty of care and a lust for adventure, towards her love of Luvah/Orc and of Danny Pink.

This is, of course, a common dilemma. Blake himself wrote about it in Milton a Poem, his first creative effort after it became evident that The Four Doctors was not working out. There he describes being visited by the angelic Ololon, whom he greets saying “Virgin of Providence, fear not to enter into my Cottage. / What is thy message to thy friend: What am I now to do? / Is it again to plunge into deeper affliction? behold me / Ready to obey, but pity thou my Shadow of Delight: / Enter my Cottage. comfort her, for she is sick with fatigue.” Ololon declines this invitation, however, and Blake quickly finds himself pulled into Milton’s posthumous vision quest without further thought of poor Catherine. It is difficult, then, to justify reading Clara’s evident loyalty to Danny differently. Yes, given the choice she opts to die on what she believes will be a burning Earth instead of becoming the last of her kind, much as Blake offered his protestations. But this isn’t an ending; it’s just a place where we can expose the truth of things.

Ah. And there’s the rub. There are two ways that a dreamlike space could go. it could reveal truth or it could reveal possibilities; trees or a TARDIS. And in the end, the Forest of the Night is a forest, offering truth in all its repressive singularity. That its moral—“be less scared, be more trusting”—is a good one doesn’t change the fact that it is exactly that: one. The invocation of Blake and the mythic heart of Albion closes down opportunities instead of opening them. As we said, this was inevitable; it’s where all efforts at vision are inevitably going to go. Blake in Doctor Who is too good an idea to only do once, but once is the only way it could ever be done. That’s the curse of Doctor Who. It can do anything, yes, but generally only once. Which means every take is the definitive one, in all its suffocating obviousness. Doctor Who does Blake was never going to be a deep dive into visionary mythology; it was going to be a tiger and a dodgy forest.

Does this mean it isn’t worth doing? Of course not. If impossibility were a reason not to do something the BBC would never have tried to shove all of space and time into Lime Grove Studio D in the first place. But it means that what it accomplishes isn’t the point either. The point isn’t the moral. It’s not even the forty-five minute experience of sitting down and watching Doctor Who. Nothing that treats the episode as a closed box whose value lies emboited within is going to work.

No, the point is simply that this happened. That we entered the Forest, were lost within it, and emerged. We saw its golden heart and communed with the spirit of Albion itself. For a fleeting instant we saw the mythic plane; we understood. And if the next morning our memories proved fuzzy, or if our accounts of it proved hard to quite stitch together, well, so be it. We don’t need to remember everything. It doesn’t need to make sense. It works better if it doesn’t. What matters is that we’ve been inside, and been changed by the experience. One night, a forest grew from nowhere to save us from the sun. And then.

June 4, 2018 @ 4:36 pm

Tyger tyger, burning bright

In the forest of the night

What immortal hand or eyes

Could frame thy fearful symmeTREEEEEEEEEEEEEEES

This is one of your best salvage jobs since the Trial articles. Superlative.

June 6, 2018 @ 10:43 pm

Rebecca Clarke set it to music, it’s so good.

June 4, 2018 @ 4:57 pm

I saw this post at half past nine this morning and at half past ten it had disappeared as if it had never been.

June 4, 2018 @ 5:00 pm

It would have been funny to do a 24-hour post that then vanishes and never appears again, but it was just an error in how I set some flags posting it, alas.

June 4, 2018 @ 5:48 pm

How do we know you haven’t done it before….hmm?

June 8, 2018 @ 3:30 pm

The Silence are allowed to comment here as well you know. Did you not read the searing take-down they did of The Impossible Astronaut which suggests they were unfairly maligned and misrepresented in a way that almost borders on racism? Ah but of course you did, I’m reading your response right now…

June 5, 2018 @ 8:47 am

It pointedly un-happened.

June 4, 2018 @ 5:37 pm

I also like how the kids are written. This is one of the few pieces of TV where the kids don’t just say things that middle-aged adults think that kids do or should say, but rather that I can imagine actual children speaking, reflecting their own views on the world.

June 4, 2018 @ 5:55 pm

https://8ch.net/doctorwho/res/41700.html

June 4, 2018 @ 7:50 pm

I figured it was something like that.

June 4, 2018 @ 8:09 pm

This episode always felt like I had actually come in two thirds of the way into an Alan Moorish Swamp Thing story, with the Doctor playing the part of John Constantine on the sidelines instead of being the center of action himself.

There were a couple of stupendous failures with the story. the lesser failure is just the scientific problem of expecting the plants to save Earth by pumping out a lot of extra oxygen. Raising the oxygen content should actually make the Earth burn faster when the flare hits, but that might have been the plant’s plan all along – incinerate the monkeyboys at the cost of the bulk of the plant life, but the seeds planted down in the soil would sprout again and the plants would once again enjoy dominion over the planet. Those bastards. At least that probably should have been how it played out.

The more important thing is that this story wrecked the entire season arc by taking less than a minute at the end, presumably the part which Moffat had written. Seeing the Earth survive, Missy exclaims “well, I didn’t expect that.” What exactly did she expect, the solar flare to vaporaize everybody on the planet? That would mean that her entire scheme she had been working on all season didn’t matter at all, since she didn’t expect any survivors anyway (and most likely not enough corpses with surviving genetic material to turn into Cybermen, not to mention her own Cybermen getting vaporized). So, what was she really expecting to have happened?

June 5, 2018 @ 7:47 am

Do you really expect Missy to have a coherent plan and not sabotage herself by being insane/stupid halfway through? We’re talking about a person who literally stabbed themselves in the back twice. I have no trouble believing she meticulously planned the whole Cybermen business but then saw the signs of the incoming solar flare and went “nah, I’ll just watch the planet burn”.

June 4, 2018 @ 8:29 pm

Oh, bravo, madam, bravo.

Although, while you make a good argument for trees as emblematic of single vision, doesn’t mean that a forest, being comprised of countless trees, must similarly represent the multiplicity of vision. At least, that’s how I have always seen it: you climb the tree up and out into enlightenment, and then you come back down, share what you’ve learned, and climb another up and out into a different part of the sky. In the iconography of this episode, the forest speaks in a multitude of voices.

I legitimately impressed you made it through this whole thing without using the word “liminal” once. I would not have been able to resist.

June 5, 2018 @ 9:07 am

I didn’t understand much of this essay but I appreciate its meticulous structure and its depth of thought,even if it proved too deep for me. Whatever I did understand I enjoyed a lot, so thank you.

Knowing nothing about Blake, I can’t really comment on how the pairing of his ideas with “Doctor Who” worked on-screen. What I remember from this episode are mostly the two things that made me angry: the unfortunate implications of the “don’t take your meds, the voices in your head are magic!” plot (that the whole DW team apparently missed) and the Doctor telling Maebh she’s not important. I couldn’t help but flash back to Eleven telling Kazran Sardick “In nine hundred years of time and space and I’ve never met anybody who wasn’t important”. Well, apparently he finally has. A scared little girl looking for help. Good job, Doctor.

June 5, 2018 @ 12:26 pm

For me it was mainly the climate-change-denialist implications (presumably unintentional, but decidedly present), the banalising “this silly thing I made up is the reason why forests are psychologically and culturally important” stuff, and the paltry, parochial shrinking from nature, strangeness and upheaval, a failure manifested especially by the phones. A feeble betrayal of a potentially enchanting concept. I am not a fan.

June 7, 2018 @ 7:17 am

Although, as this site’s own Jack Graham noted, I think, in Christmas Carol the Doctor is perfectly happy to ignore the multitudes of fridged people, and even Abigail is only taken into consideration insofar as she’s important to Kazran. Whereas here the Doctor ultimately realises the importane of Maebh.

June 11, 2018 @ 7:59 am

Ha. That is a very good point.

June 6, 2018 @ 7:33 am

“Likewise, the Forest of the Night is very pointedly not something that happens to the world. It pointedly un-happens, forgotten by everyone along with the solar flare it saves them from, even as it asserts its own Eternity. The Forest of the Night thus remains a dreamspace, where secrets can lie.”

Given that “The Lie of the Land” gets forgotten too, could it be a dreamspace as well? A strange nightmare about fascism, the power of media and the irreducible, core dickishness of the Twelfth Doctor? It certainly makes much more sense as a dream…

(Having said that, I love the idea of “In the Forest of the Night” being a dreamscape, a brief rupture in “Doctor Who” logic caused by an invasion of a different, higher, hidden logic of the world. Not many things can warp DW the way it usually warps every other genre it encounters).

June 6, 2018 @ 3:35 pm

Lovely write-up even if I had to read it half a dozen times to understand it.

“On a broader level, it is plagued by an aggressive superficiality in its relationship with Blake himself. It’s not just the literal tiger, but the fact that the title draws from Blake’s most anthologized work and offers a trite “if Blake were alive today he’d be medicated out of his genius” moral that’s as banal as it is offensive. It’s heritage theme park Blake, sticking to the most sanitized and basic points of iconography and carefully avoiding coming to any interesting conclusion, its hand adamantly declining to seize the fire. And yet as with Blake’s illustrations to Night-Thoughts the fire finds a way. ”

This was what I felt about the episode as well. There is so much promise, but it falls away to banality for the most part. I wonder if you have seen the deleted scene from the episode, which has Capaldi in his poetic best and also foreshadows Clara’s decision to not be the last of her species. The Untempered Schism becomes the source of the Doctor’s visions and he sees the forest on earth as revealing a possibility that Gallifrey is out there.

https://nerdist.com/doctor-who-deleted-scene-gallifrey-capaldi-years-exclusive/

I also felt that is perhaps this is the only episode where Jenna Coleman is unable to inhabit the Clara that was required, and a lot of it perhaps because of the writing. Clara comes across as unnaturally prosaic (unlike Listen’s Clara, for example, who would be more suited to this episode), except until the very end when she is with the Doctor to witness the fire. The crucial scene where she makes the Doctor leave just does not hit the right tone for me. Or even in the end of the deleted scene, where I would expect Clara to be much more introspective on what it means to be the last of one’s species. But I really enjoyed reading the Luvah/Orc part and I can now understand what the episode could have been .. revealing truth or possibilities.

June 6, 2018 @ 4:22 pm

I’ve never seen that scene before. Thank you! It’s beautiful and brilliant. Although I see what you mean about Clara – why would she just crush the Doctor’s hope like that, especially as she was there when he tried to save his planet?

June 7, 2018 @ 2:42 am

Yeah. Capaldi’s speech is beautiful, isn’t it? Perhaps, they cut it because they did not shoot a subsequent scene which would have dwelt on Clara’s reaction. Not only was she present when Gallifrey was saved, she actually saw Gallifrey in Listen and reached out to the the young Doctor’s loneliness. Somehow her reaction just did not fit and came across as quite callous, unless there was a subsequent scene which was not shot. But in the scene where she tells the Doctor to go, she does say that the Doctor is going home (to her student) just as she is, so she seems to think that there is the possibility of Gallifrey for the Doctor.

That deleted scene could have emphasized that Clara’s choice to remain is not about Danny and mundane normalcy, but about leaving humanity behind to get destroyed. She would rather die with humanity (her duty of care side) than run with the Doctor to the stars. And based on that sentence, it appears she was thinking that she was sending the Doctor to his home.

Capaldi’s speech should have been included as it would have worked in setting up a more ethereal dreamscape narrative and made the episode more poignant. More importantly, it also sets up the Doctor as a misunderstood outsider who sees things beyond narratives thrust on us, just like Maebh, which would make his plea to humanity to understand and listen to Maebh heartfelt, without needing that Blake line.

It is unfortunate that there were flaws in the narrative and execution when (on second thought) it could have been a subliminal, perfect episode, matching Listen and Kill the Moon in its audacity and thoughtfulness.

June 6, 2018 @ 10:46 pm

Two things:

1. I thought initially that Clara was refusing to escape on the TARDIS because of Danny, but I found the reason she gives much more interesting and much more honest actually.

2. I think you have to be a crazy Blake initiate to enjoy this episode.

June 17, 2018 @ 3:08 pm

LOVE THE ESSAY EL!

“Every Morn and every Night

Some are Born to sweet delight

Some are Born to sweet delight

Some are Born to Endless Night”

Nothing more to say, just one of my favourite of your entries now.

June 25, 2018 @ 8:35 am

Very late to the party (the past few things have been hectic to say the least), but I can’t resist chiming in.

In the Forest of the Night is my favourite episode of series 8, mostly because of its aesthetic. As someone fascinated by the mythic layer of Britain, I was bound to be charmed by this and that’s pretty much what happened. The episode swept me up so that I didn’t really mind any of the flaws.

But as with Kill the Moon, what I particularly enjoyed was the post-humanist layer. We often say that human activity will kill the planet and I think it’s at the same time hubristic and anthropocentric. True, we can harm the planet, kill off entire species etc. But we cannot kill the entirety of life on the planet. I don’t think we’d be able to manage even all of the humans (though the climate change will probably afflict us to a huge extent). And I draw a sort of grim optimism from this. Even if we murder everything on the surface, with time something will crawl out from the unfathomable oceanic depths to try again.

I also thought it was really fascinating that the solution to the problem in the story didn’t come from any human institution. I didn’t see it as advocating complacency, just a valuable reminder that not everything comes from us. Like the plastic-eating bacteria which seems like something that might help us combat the plastic pollution crisis. There’s still stuff we can do (like synthesising the substance that digests plastic, not to mention having a wider discussion about sustainability and how much plastic we should actually use), but nature still has the potential to surprise us and help us.