Fair Boy Your Eyes (Song For Eric)

The b-sides for Little Earthquakes are a mixture of fine songs that it’s difficult to see how missed the album, or that if it is clear, it comes down purely to tonal fit instead of quality—“Upside Down” and “Take to the Sky”—and the usual mix of songs that fall just short of the album tracks that did make it—“Mary” and “Sweet Dreams.” And then there is “Song for Eric,” the only song among the Little Earthquakes sessions to simply be bad. An a capella love song framed entirely in fantasy romance pablum about a “fair maiden” who will “wait all day for my sailor” that unironically includes the phrases “over hill and dale” and “you know me like the nightingale,” it is at best a cut rate version of “Etienne,” and at worst a rehash of the character-based love songs she wrote as a teenager. (It’s worth comparing specifically to “Rubies and Gold,” which is essentially the same song only with a baroquely complex musical arrangement instead of an a capella delivery.)

Exactly what happened here is hard to discern, not least because it’s one of only two Little Earthquakes-era songs upon which Amos has literally never made any sort of comment. It was on the rejected first version of Little Earthquakes, sequenced between “Sweet Dreams” and the terminally unreleased “Learn to Fly,” but the commercially released version (dumped on a limited edition reissue of “Silent All These Years” in the UK) comes from the London-based 1991 sessions with Ian Stanley that yielded “China.”

Where the second set of sessions for Little Earthquakes were an effort to reconceptualize the album away from the excessive lightness of the Siegerson tracks, these London sessions were essentially just extra. After rejecting the first cut of the album and giving Amos no end of grief (as described in “Leather”), Atlantic executive Doug Ross called Amos up after the second version to say, in his own words, “I don’t know how to tell you this, but I’ve fallen in love with your record.” (Ironically, the track that grabbed him was “Winter,” one that had been on the original version.) Still puzzling over how to promote an artist as unusual as Amos, Morris decided that the easiest thing to do would be to ship Amos off to London for a year to work the British market. With a much smaller geographic area and national radio stations, the UK had always been a more hospitable market for odd artists. Amos performed a set for East West honcho Max Hole, who as a devoted Kate Bush fan, made the leap to Amos fandom with relative ease, and Amos was up and running. And in the course of her UK residency, she found herself in the studio with former Tears for Fears member Ian Stanley cutting another set of songs.

These sessions are something of a curiosity in general—they’re by far the least remarked upon recording block for Little Earthquakes, and the songs that came out of them are a baffling mix—a handful of new songs Amos had penned between the completion of the home sessions with Eric Rosse in late 1990, a couple of covers, and a few reworkings of old material such as “China” and “Song for Eric” (and possibly “Girl” under one theory of “Thoughts”’s provenance). Some of these are absolutely extraordinary tracks—we’ll talk about the most obvious one next time—but the sessions as a whole feel vaguely directionless. This raises the question, however, of exactly when Amos actually penned “Song for Eric.” Was it one of the songs written in late 1989/early 1990 as Amos sat within her fairy circle summoning up the first version of Little Earthquakes? Or is it a bit of old schmaltz that actually does date to around the same time as “Etienne” and the other Y Kant Tori Read songs that its complete lack of emotional depth or nuance most resembles?

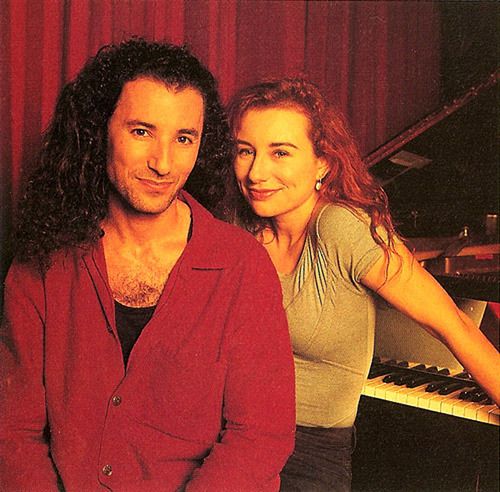

As for Eric, he is of course Eric Rosse, Amos’s then-boyfriend and co-producer. Rosse had been with Amos dating back to the Y Kant Tori Read days—Joe Chiccarelli recalls him hanging around the studio. And he’d been a major figure of encouragement in the wake of the album—Amos recalls that he was “one of the first to encourage me” afterwards, listening to her piano work and being astonished that she’d never showed it to anyone.

But for all of that, there’s a preening quality to many of Rosse’s own comments on Amos. He’s not the nightmarish controlling male figure of countless female pop origins—it’s clear that Rosse has tremendous regard for Amos’s abilities. But he also visibly wants to be a key part of her narrative—he talks in interviews of the song’s he’s proud of, and uses phrasings that take more credit than is due, such as noting that Amos “sang and played piano at the same time on one song, but for the others, I did not have her sing and record at the same time,” a phrasing that implies he had wildly more to do with “China” and indeed much of the album than his co-producer credit on four songs actually warrants. His respect for her talents and her art is clearly tremendous, but he also tangibly sees himself as being The Guy Who Discovered Tori Amos and Got Her To Follow Her Art.

And while it’s true that Rosse produced one of Amos’s best albums and four tracks off of another, it’s also true that the album Amos wrote in part about their breakup and that she solo-produced for the first time was Boys for Pele. Which is to say that whatever emotional role Rosse had in Amos’s recovery from Y Kant Tori Read, he was never essential to what she was. And if this song is any indication, moving away from him was far more important than anything he actually did.

Recorded in London in 1991, produced by Ian Stanley. Played occasionally before being retired in 1998.

Song for Eric (demo, 1990)

Song for Eric (demo, 1990)