The Dream King (Tear in Your Hand)

Tear in Your Hand (1992)

Tear in Your Hand (1992)

Tear in Your Hand (live, 1992)

Tear in Your Hand (live, 1998)

Tear in Your Hand (TV performance, 2002)

Tear in Your Hand (official bootleg, 2005)

Tear in Your Hand (official bootleg, 2007, Tori set)

Tear in Your Hand (live, 2014)

Preludes and Nocturnes

We all know where this is going, but let’s start with the actual song: a comparatively uptempo breakup song. The temptation to make another Y Kant Tori Read comparison is obvious from the description, which makes the song all the more surprising given how radically far from that it actually ends up. There are obvious reasons for this. For one, “Tear In Your Hand” is, like most of Little Earthquakes, built around Amos’s piano, which offers a jaunty descending riff doubled by Amos’s initial “yai la la lai lai lai lai” vocal line. This is not a song of swaggeringly wounded pride or of pained yearning, but something altogether more trickster-like. Amos is teasing in her vocal, maintaining a sense of humor throughout, as with “I don’t believe you’re leaving cause / me and Charles Manson like the same ice cream / I think it’s that girl.” Amos is clearly hurt by the breakup, most obviously in the bridge’s “cutting my hands up / every time I touch you,” but has already obtained a position of ironic distance.

Musically, Amos describes the way she sought to keep the song relatively still despite its energetic performance: “I heard the music as a steady motion, no change really from verse and chorus, only the bridge that leads straight back like a loop to the same toll booth where you threw in some change to go around only to end up surrounded by the place you left,” suggesting that the departure and return gives a sense of perspective and little more. It’s a good structure, well-suited to the simultaneous emotional turmoil and stasis of a breakup, and slyly foreshadowed by the opening line: “all the world just stopped.”

But the bridge is not the first moment in which the musical steadiness is disrputed—that comes when the backing music cuts out momentarily while Amos sings, “if you need me, me and Neil will be / hanging out with the Dream King.” Neil, in this case is writer Neil Gaiman, and the Dream King is Morpheus, the lead character of his landmark Sandman series of comics. This invocation marks the first moment of Amos’s trickster role within the song—the first emotion other than her stunned confusion at the breakup, and in turn is the first instance of what Alex Reed has described as “Gaiman’s coinciding with a breaking free of patterns in Amos’s songs.”

A Doll’s House

Chronology is tricky here—ultimately the two phenomenon emerged in my life simultaneously but independently, a Bader-Meinhof phenomenon cross-cutting between the two. I unequivocally encountered Gaiman first, somewhere around 1995. A committed Douglas Adams fan left in the lurch by his failure to publish any books after 1992, I made the sensible lateral expansion into Terry Pratchett’s Discworld books following the release of the 1995 DOS-based adventure game for which former Doctor Who actor Jon Pertwee had done voices, which was enough to get me in the door. Browsing a local bookstore, I found Good Omens, a book lampooning Biblical prophecy and the end of the world that Pratchett had co-authored with… some guy.

The identity of this “some guy” clarified further with the April 1997 issue of Fantasy and Science Fiction, which carried a book review by Charles de Lint of Neverwhere. This caught my eye—the book sounded right up my alley. But de Lint recommended getting the UK edition due to the US edition bastardizing some British phrasing, and so I did not pursue it with any ardor.

Around the same time I acquired Little Earthquakes where the musical emphasis on “hanging out with the Dream King” drew attention to itself. These were the days of learning about the world on the early Internet, leafing through FAQs long since lost to the mists of time. In one on Tori Amos, I learned that the line was a reference to Gaiman, at which point the name on the front of Neverwhere and Good Omens finally began to register as an important and interesting thing in its own right. I moved on to Neil Gaiman FAQs, learning the broad strokes of Sandman.

My most vivid memory of their subsequent intersection comes… ooh, this gets tricky. I remember there being snow on the ground, so logically we must still be in early 1997, since that summer was when I read A Doll’s House at CTY. I can only assume the April 1997 issue of Fantasy and Science Fiction came out a few months early in the way that periodicals often do, and that the eerie synchronicity was in full effect.

Anyway, we were visiting my uncle at his condo in Fishkill, New York. I was the sort of child who would, twenty years later, be vividly depicted in Saturday Night Live’s “Wells for Boys” sketch (https://youtu.be/BONhk-hbiXk ), and so my reaction to this turn of events was to hole up in one of his bedrooms with my Discman and Little Earthquakes. I’d seen a comic shop on the way into the condo development, so eventually I put on my coat and walked down there. I’d dropped out of actually buying superhero comics a few years earlier, so my interest was largely in the “oh, something to do” vein, but I found myself browsing back issues and eventually rifling through the available issues of Sandman. Armed with my FAQ knowledge, I plucked two out of the bin, the standalone stories “Ramadan” from issue #50 and “The Tempest” from #75, the book’s final issue. I went back to my uncle’s room, set the album to play one more time, and started to read.

The synchronicity never really let up from there.

Dream Country

In the summer of 1991, Gaiman attended the San Diego Comic-Con, as a featured guest. There he picked up one of his four consecutive Eisner Awards as Best Writer. During a signing, he was approached by Rantz Hoseley, who slipped him a cassette tape featuring an early prototypical version of Little Earthquakes and Amos’s number on the back, noting that “She sings about you on one of the songs – don’t sue her.” (Gaiman recalls it containing “50 per cent of the songs that ended up on Little Earthquakes.” Given that it included “Tear in Your Hand,” it must be a combination of the Siegerson and Rosse/Amos sessions, although given that all but two songs for the album were already recorded at this point, Gaiman’s figure seems low. Hoseley, of course, had also been Amos’s path into Sandman, which had been among the comics he’d given her while crashing at her place in 1990, and was thus why the song has a line about him in the first place.)

Gaiman eventually got around to listening to the tape, and in his telling was pleasantly surprised that it was not a badly done metal album. Impressed, he called the number and suggested that Amos was quite talented and should look at doing music as something other than a hobby, to which Amos laconically replied, “that’s a relief, because Little Earthquakes is being released in a couple of weeks”

By this time, Amos was London-based upon the insistence of her label, and so after some further phone conversations Gaiman showed up at an early show of hers at the Canal Brasserie. (The show is early enough in Amos’s career to be poorly documented, and doesn’t show up in any of the comprehensive lists of Amos’s shows, but a review of it in the October 12th, 1991 issue of Melody Maker suggests that Amos made for “absolutely compelling, but uncomfortable listening,” declaring her “a joy to behold, in spite of the pain” and comparing her favorably to Diamanda Galas, who is dismissed as a “hysterical, feminist, psychotic babbler.) As Amos describes it, “We met at a time when celebrity hadn’t made us guarded about people. Also, there was never any confusion that it was going to be a romance, and there’s a sacredness to having a male friendship where that doesn’t come into it.”

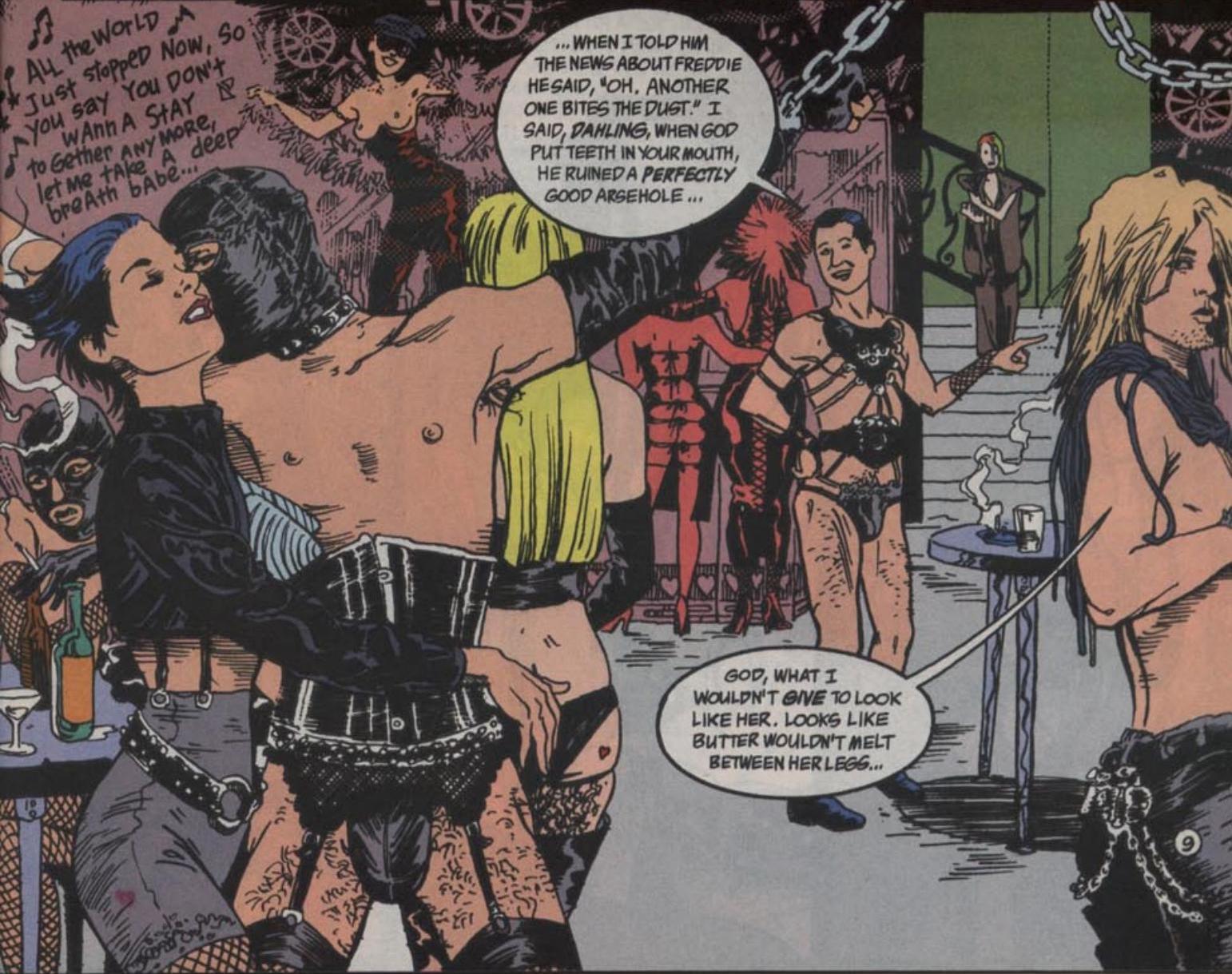

Gaiman quickly began incorporating references to Amos into Sandman, most obviously having the character of Delirium physically resemble her in a number of scenes, and in the first issue of Brief Lives, the most Delirium-centric arc of the series, having “Tear in Your Hand” playing in the background of a bondage club. This game of mutual reference has continued across their careers, as will no doubt be documented over the course of this blog and The Last War in Albion.

A Game of You

Cynical as the question is, it is worth asking what Amos and Gaiman get out of this relationship. Obviously non-cynical answers abound. For one thing, they just actually and legitimately get along and enjoy each other’s friendship. Amos speaks about the way that Gaiman has supported her at a variety of difficult times. Gaiman speaks about the way in which Amos is creative and insightful and simply cool to be around.

But there are dimensions to their friendship beyond the basic level of emotional attachment. After all, Amos and Gaiman are both friends with lots of people, but you don’t see Maynard James Keenan or Lenny Henry making cameo appearances in multiple works across the whole of their careers. (Amos does make a chain of Nine Inch Nails references across her early albums before having a falling out with Reznor, but that ultimately doesn’t refute the point I’m making here) There’s something about this particular friendship that can be productively aestheticized by both.

Amos is a strange and visionary artist, but she is also at the end of the day a shrewd and canny practitioner of the business of being a pop star. And Gaiman is much the same in his field, identifying an aesthetic and style that would sell and riding it on an ever-upwards pointing career path from comics to novels to television. Both of them accomplished this in something akin to the classic pop star way, creating a self that is both persona and brand. More to the point, both engage in a repeated game of reference and allusion. In Gaiman, these allusions are generally outward-facing: his works reward the learned reader who gets the references to classical mythology, literature, or pop music scattered throughout. It’s a familiar passtime from the geek media scene that Gaiman came up through, but turned away from obsessive recitations of ancient Batman comics and towards Milton, Egyptian mythology, and Elvis Costello. Amos is a particularly frequent reference point, but still just one of an extended textual game.

Amos, meanwhile, is not so straightforward in her allusiveness. She refers to things within the hall of mirrors of an evolving personal mythology. Often the point is not to be understood but to mystify. This is not, to be clear, a state defined by the absence of understanding, but rather by its incompleteness—by the presence of confusion. This requires that there be islands of clear sense and relatability, as already seen at length in “Silent All These Years.” And it is here that Gaiman finds his utility, offering a consistent anchor point within her music—a frequent reference listeners know how to make sense of.

But in each case their cross-referencing assumes an overlapping audience, the existence of which clarifies the nature of each party. For Gaiman, it becomes clearer that his appeal lies in no small part in his successfully packaging his brand of sweetly gothic geekery in a way that appeals to female audiences. For Amos, meanwhile, there is the clear realization that she belongs to a subculture of weirdo theater kids with a fondness for eyeliner. Neither of these are stunning realizations, obviously, but neither are they things that follow self-evidently from a purely formal analysis of their art. They are obvious facts about each one’s fandom in practice, but understanding why this should be so is most easily accomplished by viewing the two as a binary star system, their art as a glorious folie à deux.

Recorded in Los Angeles at Eric Rosse’s home studio in 1990, produced by Rosse and Tori Amos. Played throughout Amos’s career.

January 9, 2020 @ 11:36 am

As a kid, this was the one Tori song I knew because of the Sandman connection. I grabbed it off Napster. I remember a girl yelling ‘Tori!’ when she saw me reading Death: The High Cost of Living in class