A Man On My Back (Me and a Gun)

CW: Rape

CW: Rape

Me and a Gun (TV performance, 1992)

Me and a Gun (official bootleg, 2007, Pip set)

It is one of the most harrowing things in the history of pop music. The bulk of adjectives for it seem to fall short, fatally undermined by the fact that they’ve already been used for so many lesser songs. Brave? Raw? Powerful? Obviously. But all of these are understatements. Ultimately, the vocabulary of pop music begins to falter here. “Me and a Gun” exists in a different space than anything else. Alex Reed, writing about industrial music in Assimilate, notes that nose forms an extreme limit that you cannot progress past: there is simply a boundary past which you cannot create more or harsher noise. In its own way, “Me and a Gun” does the same thing. Its aesthetic project is closed definitively after four minutes; nothing else like this can ever be done except as a pale and frankly offensive imitation.

In January of 1985, a few months after moving to Los Angeles, Tori Amos agreed to give a guy a ride home after a show at a bar. He raped her over the course of several hours holding her hostage. He demanded that she sing hymns for him, which she did while literally pissing herself, listening to his threats of how he’d take her to share with his friends and then kill and mutilate her. Eventually, needing a drug fix, he let her go.

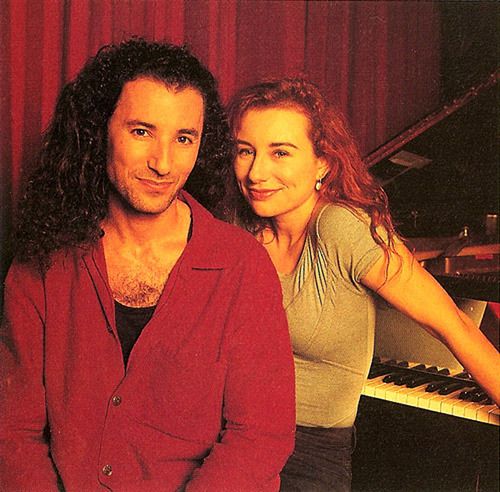

For years, Amos was unable to deal meaningfully with the experience. Much of the vapidity of Y Kant Tori Read comes from the fundamentally doomed contradiction of an artist whose internal landscape is dominated by one thing trying desperately to write about anything but that. Even Little Earthquakes has an odd relationship to it, spending most of its time processing adjacent thoughts and emotions. But while in London in August of 1991, Amos went to see Thelma and Louise and found herself assailed by the memories of what had happened six and a half years earlier. Withdrawing into herself for several days, she wrote “Me and a Gun.”

It is easy to see “Me and a Gun” as a simpler thing than it is. Amos’s decision to arrange it a capella and its aggressively vulnerable autobiographical nature conspire to make it seem straightforward: a woman narrates the events of her rape. This obscures the degree to which the song is carefully crafted. To take the most obvious point, Amos’s rapist used a knife—Amos changed it to the more dramatic sounding title. And Amos makes a lot of careful choices about what to focus on. Obviously one cannot narrate one’s own rape without a degree of abjection, but Amos doesn’t really lean into that aspect of it—the detail of her urinating on herself, for instance, comes from an interview, not from the song.…

Song for Eric (demo, 1990)

Song for Eric (demo, 1990) Tear in Your Hand (1992)

Tear in Your Hand (1992) Little Earthquakes (1992)

Little Earthquakes (1992) The traditional Eruditorum Press post-holiday ebook sale is running from now until January 2nd.

The traditional Eruditorum Press post-holiday ebook sale is running from now until January 2nd.  Precious Things (live, 1991)

Precious Things (live, 1991) Flying Dutchman (1992)

Flying Dutchman (1992)

The only thing missing is the actual tense relationship between the Amoses. In fact Ed Amos is consistently supportive of his daughter, and has been throughout her life, from chaperoning her as she played Georgetown gay bars in her teens to any number of comments to the press in which he speaks warmly of his daughter’s career. This is not, to be clear, because he’s a radically progressive Christian. By all appearances he’s solidly moderate—Amos has spoken about her father’s support for the civil rights movement, but also made wry comments about how he’s evolved to seeing gay people as individuals instead of as a homogenous mass of “the gays.” Instead there’s a sort of wry pragmatism to his assessment of his daughter—one rooted in a profound respect for her ability. The relationship is perhaps best summed up by a comment Amos attributes to him in several interviews to the effect of “what would you have written about if I had been a dentist?”

The only thing missing is the actual tense relationship between the Amoses. In fact Ed Amos is consistently supportive of his daughter, and has been throughout her life, from chaperoning her as she played Georgetown gay bars in her teens to any number of comments to the press in which he speaks warmly of his daughter’s career. This is not, to be clear, because he’s a radically progressive Christian. By all appearances he’s solidly moderate—Amos has spoken about her father’s support for the civil rights movement, but also made wry comments about how he’s evolved to seeing gay people as individuals instead of as a homogenous mass of “the gays.” Instead there’s a sort of wry pragmatism to his assessment of his daughter—one rooted in a profound respect for her ability. The relationship is perhaps best summed up by a comment Amos attributes to him in several interviews to the effect of “what would you have written about if I had been a dentist?” Happy Phantom (demo, 1990)

Happy Phantom (demo, 1990) Upside Down (live, 1991)

Upside Down (live, 1991)