Jerusalem Review

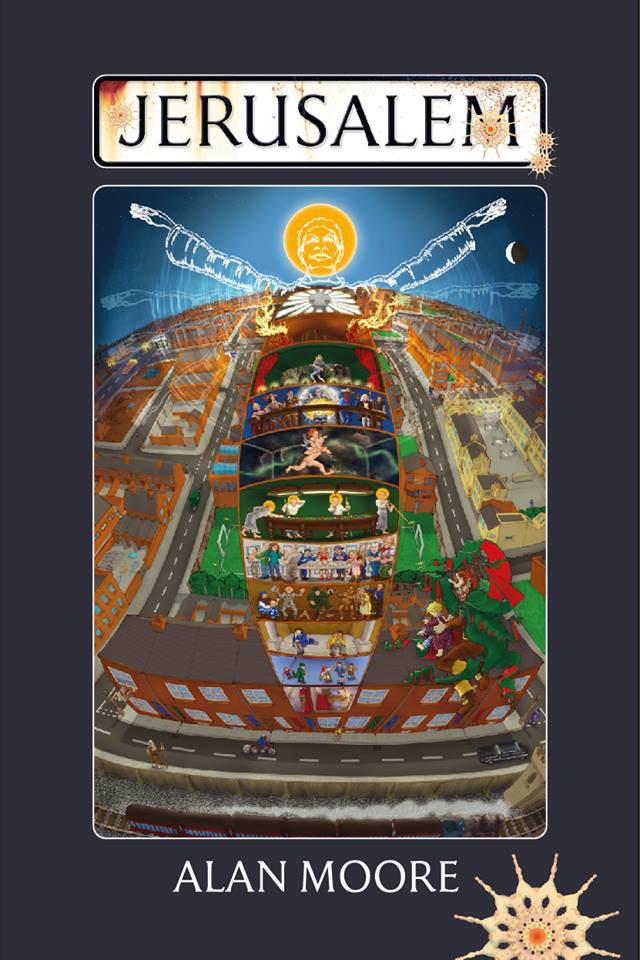

It’s easy, with something like this, for the weight of expectations to become crippling. The stakes are such that anything short of it self-evidently joining Watchmen and From Hell on the list of Major Alan Moore Works would seem like something of a failure, and one can almost imagine reviews that sadly say “it’s not one of the top twenty works of the entire history of English literature – merely one of the top fifty.” At this point in Moore’s career the arrival of a would-be major work is as much an occasion for critical knife-sharpening as anything – there’s a grim and awful sense of critics realizing that there aren’t going to be that many more opportunities to declare that the great man has made a real and proper misstep. A preposterously long and ambitious novel named in part for William Blake’s legendarily quasi-coherent last prophetic work really does seem like a prime opportunity for anyone desperate to make the case that Moore’s finally had one spliff too many, and there’s no shortage of those.

It’s easy, with something like this, for the weight of expectations to become crippling. The stakes are such that anything short of it self-evidently joining Watchmen and From Hell on the list of Major Alan Moore Works would seem like something of a failure, and one can almost imagine reviews that sadly say “it’s not one of the top twenty works of the entire history of English literature – merely one of the top fifty.” At this point in Moore’s career the arrival of a would-be major work is as much an occasion for critical knife-sharpening as anything – there’s a grim and awful sense of critics realizing that there aren’t going to be that many more opportunities to declare that the great man has made a real and proper misstep. A preposterously long and ambitious novel named in part for William Blake’s legendarily quasi-coherent last prophetic work really does seem like a prime opportunity for anyone desperate to make the case that Moore’s finally had one spliff too many, and there’s no shortage of those.

I say all of this mainly to stress what it in practice means that Jerusalem has largely gotten positive reviews, including a good writeup in Entertainment Weekly, which endearingly called Moore “an angry old man who writes like an angry young man.” Because not only is Jerusalem self-evidently good, and moreover good in a really calm, untroubled way that’s utterly unconcerned with the question, it’s enjoyable. It demands attention, but it is not a difficult novel. Certainly it is unlike Voice of the Fire, whose deliberately obtuse first chapter went out of its way to winnow the readership down to its most sympathetic core. There is a famously difficult chapter about Lucia Joyce that Moore’s been talking up in interviews, but it’s much of the way through the book and can be skimmed and revisited later in a way that “Hob’s Hog” cannot. It’s in no way an “easy” book, but it’s equally absurd to call it a difficult one. Whatever the book’s literary merit – and I’m about to argue that it’s significant – it’s also just a tremendously well-done piece of writing by one of the great storytellers of our age. I loved reading it. You should clear some time in your schedule and have a go at it.

At the heart of the novel is Northampton. Moore has been deftly mythologizing the place for a while now, but this is clearly the weightiest attempt. Within this mythology, it is the center of the world, which makes sense because its Guildhall has a statue of an angel on it with a sword that actually looks kind of like a snooker cue, and so obviously it’s where the four archangels play their eternal game of snooker that decides the fate of all things within the four-dimensional block universe we inhabit by endlessly cycling through our illusions of consciousness. Plus Alan Moore lives there, or at least Alma Warren, the middle-aged artist producing a career-defining thirty-five work exhibit as an act of magic to try to save the working class neighborhood of the Boroughs and obvious genderswapped authorial insert. She’s a descendent of Snowy Vernall, who could see through time, after all.

It’s cheeky and brazen, so that when in the first chapter Warren reflects on her appointed task and the narration reflects that “she wasn’t going to have to simply do these pictures. She was going to have to do the fuck out of them” before dropping a section break and commencing “And she did,” it’s not even fair to call it subtext. But in the end, Jerusalem is willing to take for granted that you’ll buy its mythic Northampton and stay to see the depth of the concept. And the depth is staggering, not just in the fact that there really are 1250 pages of gorgeous and fascinating detail to be had about the mythic history of these couple blocks of Northampton, but in terms of what Moore is accomplishing in telling this story.

Most obviously, and a point the book trumpets, it is endeavoring to create a literary mythology that is distinctly and fundamentally working class. It’s impossible to overstate the ways this fact permeates Jerusalem. Perhaps most fundamentally, it means that the mythology of the Boroughs is rooted in a sense of its own disappearance. Indeed, its own destructor – Moore revives the image of the Destructor from the back pages of some of the early Dodgem Logics to play a major role in the book – an old incinerator built in the Boroughs that comes to symbolize an entire cultural rhetoric of waste populations. It’s not so much a mythology under siege as under demolition order, with only a couple intransigent squatters left inside. Moore finds much of meaning in this image – a line he’s repeated talking about the book is “You may not want to go to the Boroughs but the Boroughs is coming to you.”

Moore makes a persuasive case to this effect, particularly in a later chapter that parallels a history of British money with the life of a local lefty radical, and it’s one of the highlights of the book. But crucially, it comes in the same section of the book as the expansive overview of the history of Northampton and the world from 2006 on to the end of time, which is to say that even it, one of the sections of the book with the most obvious and direct consequences, ends up being one component of a much larger and richer tapestry.

Indeed, it’s perhaps worth talking about the way in which the book fits together as a narrative. I didn’t count the number of viewpoint characters it has, but I expect you’d find a number somewhere around two dozen if you did, spread across several centuries, with their narratives generally told in nothing like chronological order, whether from their perspective or from Northampton’s. As a result, it is not a novel that trades on a traditional sense of suspense regarding plot. “What’s going to happen” is generally not what’s driving the book forward. Instead the book’s resolution amounts to a large number of pieces clicking into place – a series of moments where you go “oh, so that’s what that bit was all about.”

And it’s largely structured like that. There are thirty-five chapters, which divide fairly neatly into three tranches of eleven, with an additional chapter tacked onto the start and finish of the book to frame it. The first eleven spend a bit of time jumping around characters and generally setting up the Boroughs before turning into a series of chapters focusing on the Vernalls over a couple of generations. This segues nicely into the middle eleven, which actually form a linear story focusing on the same set of characters (though still jumping around perspectives), specifically the story of Alma Warren’s brother choking on a piece of candy – an event drawn straightforwardly from Moore’s own life, or at least, from his brother’s. (And yes, that’s eleven straight chapters of a 1250 page book about a small boy choking on a piece of candy. It’s enthralling. One of them’s from the point of view of Asmodeus.) Finally there are what might be thought of as the ambitious chapters – a string of eleven that contain the formal experiments like the Lucia Joyce chapter, the chapter written as a mock Samuel Beckett play, and the chapter written in verse, as well as some calmer things like the history of money, the end of time, or a chapter from Alma Warren’s perspective that gives tremendous insight into Alan Moore’s bathtime rituals. (He’s a fan of Lush products, and really, who isn’t?) It’s these last few chapters where the book’s biggest thrills lie – they regularly set up extraordinary moments where vast chunks of the book suddenly realign themselves in your mind, revealing images and concepts you didn’t know you’d been reading about for over a thousand pages. The penultimate chapter, in particular, casually weaves together strands of the book going back to its earliest chapters in a way that is obvious and stunning in the manner of a great plot twist, even though nothing surprising happens per se, and indeed almost everything that does happen is something that’s been described by characters in other chapters.

This suits the book’s basic premise – an unchanging and eternal block universe experienced through the illusion of linear consciousness. Indeed, Moore uses the metaphor of reading a book to describe the notion at one point. It’s a dazzling case of form following function – a book structured to demonstrate the compelling beauty of its central premise. And frankly, “block universe” is a pretty good description of the majestic brick that is the physical book. But more to the point, this has always been what Moore is good at. From the densely crystalline structure of Watchmen to the forensically organized sprawl of From Hell, Moore’s ability to craft a vastly intricate system has always been unparalleled. Jerusalem is the biggest and most personal one he’s ever done, and almost certainly will ever do. That’s not to say it’s some sterile intellectual exercise – Moore is a gifted chronicler of ordinary humanity at its most joyous and agonizing, and he puts that skill to good use throughout the book. That, in many ways, is the point of an exercise like this: the individual details are as majestic as the whole.

Which circles back to where we started, I suppose: this is Alan Moore’s magnum opus, with all that implies. There’s scads to say about it – I strongly suspect it will be the ending of The Last War in Albion (which is not to say it’ll be a hard cut-off point – I’m sure I’ll follow WicDiv and Injection to their endpoints and include the Bumper Book and all that), simply because I can’t imagine the world is going to serve up a better one. It’s the fullest and most complete realization of the vision and talent of one of the greatest writers of his age. I envy each and every one of you who gets to dive in for the first time, and cannot wait to get to dive back in myself.

September 13, 2016 @ 12:52 pm

Love it! Throwing a bit of chum to blood the water. The repeated references to his hypercubic ambition remind me of Perec’s La Vie mode d’emploi / Life: A User’s Manual. Can’t wait to find out from the brick itself.

September 13, 2016 @ 2:27 pm

I can’t help but think when reading this of the kind of weaving together of often seemingly irrelevant information and story threads we get in Cryptonomicon, though it seems like Moore’s gone way beyond that here…

But what I’m REALLY curious about is how this jives with the fact that, like, from the description this kinda seems to be the basic conclusion of The Invisibles as well, with the characters becoming aware of the illusion of time. It seems like the two great magicians keep coming back to this basic idea. I mean, I’m sure that’s more LWIA fodder but I wonder about where their understanding of this stepping-out-of-time breaks apart and goes in separate directions.

September 14, 2016 @ 10:07 am

I’m half a chapter in and it’s hooked me already. The imagery of the heavenly shop-fitters manages to be simultaneously beautiful, mundane and transcendent. My initial fears that this would be a retread of Voice of the Fire were immediately dispelled. Moore seems to be mythologising Northampton in much the same way Moorcock did his own home city in Mother London. Which BTW Eruditorum people if you haven’t read please do. It’s right up your collective alley I suspect.

Interesting observation re Morrison and The Invisibles Sam Keeper. I guess in ideaspace it’s possible to explore the same journey from different angles.

Moore really is some kind of bloody magickal genius isn’t he?

September 19, 2016 @ 8:37 pm

Northampton is my home town, and it’s frankly surreal to see what is – to be frank – kind of a shithole being discussed in such terms. Very excited to read this.