Let’s Kill Hitler Again

Hi all, sorry about the extended time away. Think of it as a winter hiatus, a polar opposite to, say, the summer hiatus preceding Let’s Kill Hitler. Anyways, I’m back! And I’ve six thousand words to share.

Hi all, sorry about the extended time away. Think of it as a winter hiatus, a polar opposite to, say, the summer hiatus preceding Let’s Kill Hitler. Anyways, I’m back! And I’ve six thousand words to share.

I just happened to rewatch Series 6 recently with very good friends, so it’s on my mind, esepcially Let’s Kill Hitler. It’s one of those episodes that, for me, gets better every time I watch it – it’s very amenable to esoteric exploration, and being so familiar with all its beats, I no longer notice the tonal whiplash and the jarring pace. “Plus, she’s a woman” still sticks out like a sore thumb, but still, that’s a relatively minor complaint compared to all the wonderful stuff going on in this story, and even more so in the context of its production.

For those unfamiliar with the production schedule for Series 6, many of the stories were shot or placed out of order. Black Spot, for example, was repositioned to the first half of the series, switching places with Night Terrors. Let’s Kill Hitler, on the other hand, started production after they’d already filmed The Girl Who Waited, The God Complex, and Closing Time, even though it was meant to precede those stories in the broadcast schedule. So there’s a sort of foreknowledge to the production of this story – as if it were traveling backwards in time and inserting itself into a flow of events that had, in effect, already happened.

And I think this is important to understand when decoding LKH, because the show itself seemed to fully realize its aesthetics with Nick Hurran’s direction of The Girl Who Waited and The God Complex, where the visual elemt to the storytelling is every bit as (if not more) compelling as the stories themselves. Which is not to say that Moffat’s tenure was never about visual storytelling prior to Hurran, only that Hurran really took it to a stratospheric level. And surely Moffat and his production team realized this as Hurran’s work was already done by the time they got around to making Let’s Kill Hitler. As such, I’m inclined to consider LKH primarily in terms of its visuals and aesthetics, because that’s where a huge part of the storytelling occurs, though there are many thematic layers worth exploring as well. Which we will.

The Wheatfield

The very first scene of this episode was actually the very last one shot for the entire series – after The Wedding, in fact, because the production team needed to let the wheat grow. So I’m not surprised that the visuals and aesthetics and thematics of this scene are impeccable, helping it to function as a microcosm of the episode as a whole. Consider the fact it’s filmed out of order, and travels back to be inserted at a particular time and place, which is true for LKH, but is also true for the conceit of Melody “inserting” herself into her parents’ history, not to mention how the character of Mels is inserted into the show’s mythology itself. I find this kind of recursion to be absolutely delightful.

The very first scene of this episode was actually the very last one shot for the entire series – after The Wedding, in fact, because the production team needed to let the wheat grow. So I’m not surprised that the visuals and aesthetics and thematics of this scene are impeccable, helping it to function as a microcosm of the episode as a whole. Consider the fact it’s filmed out of order, and travels back to be inserted at a particular time and place, which is true for LKH, but is also true for the conceit of Melody “inserting” herself into her parents’ history, not to mention how the character of Mels is inserted into the show’s mythology itself. I find this kind of recursion to be absolutely delightful.

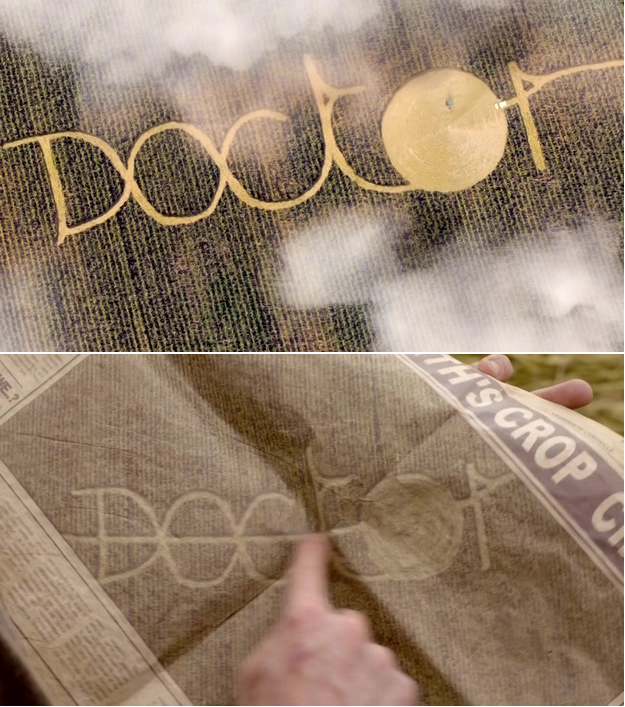

I also think it’s very intentionally self-conscious in this way. Consider the fact that Amy and Rory are making crop circles as a way of invoking the Doctor. “Loop-the-loop,” Amy says at one point during the initial drive through the fields. When the Doctor arrives, he’s come from the future – he’s holding an aged newspaper detailing the crop circles. And, as it turns out, the picture in the paper doesn’t just point to the past, while existing in the present, it also forecasts the future, as the word “Doctor” has a strikethrough line through it, as if the Doctor were being crossed out, which of course functions as prophesy, both in terms of Melody’s arrival in the Corvette and her subsequent attempts to kill the Doctor. It’s frankly amazing that such a simple visual could resonate so strongly with the rest of the episode.

But so much of this episode trucks in repeated imagery, and using visual shorthand as a way of creating thematic threads. The first shot of the wheatfield itself, for example, is purely visual. On the one hand, it evokes a similar shot at the beginning of Vincent and the Doctor, a story in part about art and aesthetics. On the other hand, the wheatfield itself carries certain long-standing mythological connotations. The myth of Demeter and Persephone, for example, one of death and rebirth, resonates with the mother/daughter relationship between Amy and River. Amy, the figure of Demeter, weeps for the loss of her daughter, but Persephone must have her own life, and make her own choices, to become a goddess in her own right. On the masculine side, many grain gods are killed at harvest so the land may be “reborn” come spring. Considering the death and rebirth of the Doctor here, just the location of the wheatfield is terribly apt.

We might even think of it as the Elysian Fields, an afterlife for those “happy heroes for whom the grain-giving earth bears honey-sweet fruit flourishing thrice a year, far from the deathless gods, and Cronos rules over them,” as Hesiod puts it, though of course much of this episode isn’t about being happy, per se, but quite the reverse. However, I stand by a mythological take, because so much of this episode touches on aspects of religion, and particularly the nature of Grace.

But it’s also an episode about repression. Specifically, how Amy has to repress her emotions in service to her larger ideals. In this shot, Amy hugs the Doctor while hoping he’s found her missing daughter, but of course he hasn’t, because River’s specific history has already been inserted or “fixed” into the established timeline of her parents. So Amy has to bury her disappointment, like a grain goddess planting seeds for the next wheat crop.

But it’s also an episode about repression. Specifically, how Amy has to repress her emotions in service to her larger ideals. In this shot, Amy hugs the Doctor while hoping he’s found her missing daughter, but of course he hasn’t, because River’s specific history has already been inserted or “fixed” into the established timeline of her parents. So Amy has to bury her disappointment, like a grain goddess planting seeds for the next wheat crop.

There are other visual motifs established in this scene that pay off “later,” either in this episode or “future” ones– the TARDIS in the center of a circle, the X motif created by Amy and Rory’s car, the halo of the sun around Mels, which we’ll get to when we get to in a bit. It’s a fun thing, like that Red Corvette juxtaposed against the Blue Box, imagery that goes back to The Eleventh Hour, and continues on in The God Complex (which, as stated before, was already filmed before LKH went into production). Considering this entire scene was the last scene produced for Series Six, I really appreciate how much “foreknowledge” of things to come seems to have informed the construction of the scene itself.

The Mirrors

Much as I want to dive into the abstract symbolism, the first thing to point out is all the mirrors. As I’ve said on previous occasions, the use of the Mirror is probably the most significant aesthetic in this period of Doctor Who. The Mirror is used both literally (as in this shot from Day of the Moon) and extensively – the Siren being able to travel between worlds through any kind of reflective surface in Curse of the Black Spot, for example, and then there are the myriad “mirrorings,” from the Doctor first seeing his own image reflected to him by the mirror-monster Prisoner Zero in The Eleventh Hour, to more fractalized juxtapositions like The Doctor, Rory, and Strax all partaking of a Warrior/Healer dynamic in A Good Man Goes to War. And this isn’t just a matter of style – no, the mirror is most definitely symbolic of the primary thematic inquiry into the nature of Identity. Indeed, the repetition of the Question — “Who Are You?” — in every episode makes that quite clear.

Much as I want to dive into the abstract symbolism, the first thing to point out is all the mirrors. As I’ve said on previous occasions, the use of the Mirror is probably the most significant aesthetic in this period of Doctor Who. The Mirror is used both literally (as in this shot from Day of the Moon) and extensively – the Siren being able to travel between worlds through any kind of reflective surface in Curse of the Black Spot, for example, and then there are the myriad “mirrorings,” from the Doctor first seeing his own image reflected to him by the mirror-monster Prisoner Zero in The Eleventh Hour, to more fractalized juxtapositions like The Doctor, Rory, and Strax all partaking of a Warrior/Healer dynamic in A Good Man Goes to War. And this isn’t just a matter of style – no, the mirror is most definitely symbolic of the primary thematic inquiry into the nature of Identity. Indeed, the repetition of the Question — “Who Are You?” — in every episode makes that quite clear.

So we’ve got a lot of mirrors to cover in Let’s Kill Hitler, both literal and figurative. Going back to that opening scene, for example, we get two shots of the crop circles – one in the present, an aerial overhead shot, and one from the future, which is represented as being from the past via an old yellowed newspaper. There’s a slight difference to the pictures, and this is played as both foreshadowing the arrival of Mels, and as a thematic – her intent to kill the Doctor, hence the “strikethrough” motif in the older/future picture. What this demonstrates is that even when mirroring is figurative – through some kind of duplication, for example – it is still highly relevant.

With that in mind, let’s turn to the first literal mirror in the story, which is placed in Amy’s bedroom. The scene is supposedly in her teenaged years, as she hangs out with Rory and Melody. Rory is the one reflected in the mirror, with Amy in the center. This suggests so much – Amy is the center of Rory’s universe, for example. Also, however, is how child-Rory has been depicted in the Leadworth montage – the blind man in Blind Man’s Bluff, keeping him from seeing that no one is paying him any attention, which goes back to him playing Hide-And-Go-Seek in Amy’s house, while she and Mels don’t go looking for him. Well, now Rory’s in the Mirror, and his fate is about to be reversed – here he’s finally seen, as the young man he is, and more importantly as the young man in love that he is.

It’s especially clever that it’s Melody who points out the truth of Rory and Amy to Rory and Amy. She herself almost acts like a mirror, reflecting the couple back at them, and this is really so sweet considering she’s their daughter and all. But there’s a nifty bit of time-loopiness here as well. Many time travel stories hinge on the consequences of changing the past, and how to avoid paradoxes and all that. This is quite different. Melody’s actions are the exact opposite of that when it comes to Amy and Rory. She doesn’t try to change her parentage, instead she acts to confirm it, to “fix” it like one might “fix” a photograph like we used to back in the old days when it was all paper and silver halide chemicals.

Not that Mels is beholden to such a philosophy. Indeed, as the title suggests, she’s got no problem with going back in time killing monsters. We’d think from the title of the episode that this is what the story is actually all about, but it’s not – once Hitler’s in the cupboard and Melody regenerates—

–actually, hold up, there’s an oft overlooked bit of symbolism here that’s particularly delicious. No, not Hitler in the cupboard (though it’s quite funny, and obviously plays on foreknowledge of the next episode up, Night Terrors, where all the monsters are put in the cupboard), but the bit where Mels announces she’s been shot. She falls onto a broken stone table, presumably cleaved by the TARDIS crashing through the wall, and it’s here that she’s resurrected. I can’t help but think of The Lion, The Witch, and The Wardrobe, which will be blatantly invoked at Christmas. In the Narnia story, the great lion Aslan’s sacrifice occurs on a stone table, causing it to crack. There’s even a specific line in the Narnia story, as Aslan explains that the Witch “would have known that when a willing victim who had committed no treachery was killed in a traitor’s stead, the Table would crack and Death itself would start working backwards.”

–actually, hold up, there’s an oft overlooked bit of symbolism here that’s particularly delicious. No, not Hitler in the cupboard (though it’s quite funny, and obviously plays on foreknowledge of the next episode up, Night Terrors, where all the monsters are put in the cupboard), but the bit where Mels announces she’s been shot. She falls onto a broken stone table, presumably cleaved by the TARDIS crashing through the wall, and it’s here that she’s resurrected. I can’t help but think of The Lion, The Witch, and The Wardrobe, which will be blatantly invoked at Christmas. In the Narnia story, the great lion Aslan’s sacrifice occurs on a stone table, causing it to crack. There’s even a specific line in the Narnia story, as Aslan explains that the Witch “would have known that when a willing victim who had committed no treachery was killed in a traitor’s stead, the Table would crack and Death itself would start working backwards.”

It’s interesting, then, that Melody is one who is the “willing victim” here. Mind you, at this point, she hasn’t committed any treachery – instead, she is killed rather than “Zimmerman,” the actual traitor that Hitler was shooting at. And it’s almost as if death runs backwards – she regenerates, becoming young again and yet mature all at the same time. Interestingly, the Doctor also falls upon the table after he’s poisoned, and he too will end up being resurrected.

Anyways, I was talking about mirrors. There’s a lovely mirror over the fireplace in Hitler’s office, which comes directly into play after Melody regenerates. There’s even a clock on the mantle, shades of Girl in the Fireplace. Melody checks herself out in the mirror, noting her magnificent hair (it’s practically a lion’s mane, or perhaps a halo) as well her teeth – for she has a monstrous mouth as it turns out, a mouth that can kill.

And of course, now we’re at the point in the story where the big Reveal has occurred, as well as a the big Reversal. This is not a story about killing Hitler – nor is it the anticipated story of tragedy porn predicted by so many after A Good Man Good To War. This is ultimately a story about River Song, who she is and how she came to be herself. The narrative substitution has taken place. Well, except that’s definitely going to kill Hitler – with the Doctor playing Hitler in her mind. She’ll even succeed. The Doctor properly dies here (and in the moment when he realizes he’s been poisoned, the mirror over the fireplace looms in the background at the top of the frame). And sure, she’ll just end up resurrecting him, as if she were Aslan himself, but there’s a nice mirroring to that final scene, where the Doctor sends Amy and Rory off to speak to her, just as he sent away River towards the end of Big Bang to speak to Amy, whispering something in her ear (telling a bedtime story) to inspire after he’s gone.

And of course, now we’re at the point in the story where the big Reveal has occurred, as well as a the big Reversal. This is not a story about killing Hitler – nor is it the anticipated story of tragedy porn predicted by so many after A Good Man Good To War. This is ultimately a story about River Song, who she is and how she came to be herself. The narrative substitution has taken place. Well, except that’s definitely going to kill Hitler – with the Doctor playing Hitler in her mind. She’ll even succeed. The Doctor properly dies here (and in the moment when he realizes he’s been poisoned, the mirror over the fireplace looms in the background at the top of the frame). And sure, she’ll just end up resurrecting him, as if she were Aslan himself, but there’s a nice mirroring to that final scene, where the Doctor sends Amy and Rory off to speak to her, just as he sent away River towards the end of Big Bang to speak to Amy, whispering something in her ear (telling a bedtime story) to inspire after he’s gone.

So already, Let’s Kill Hitler is trading on the events and aesthetics of previous and future stories. It is using its own shorthand, in other words, in an act of narrative compression. Which is something that can really only be fully exploited in serialized storytelling, which has enough time and space to establish its own language in the first place. And it really kind of has to, in this case, given that it’s simultaneously designed as a season-opener as well as a cliffhanger resolution, and especially that it’s got a lot of emotional heavy lifting to pull off while playing in the sandbox of a farcical romp.

The Voice Interface

Not all mirror shots literally involve a mirror. Yes, the Doctor dying in his TARDIS includes a literal mirror shot – his face against the glass floor at a crucial moment of grace – but that’s not the most interesting mirror here. The more interesting one, of course, is the Voice Interface.

Not all mirror shots literally involve a mirror. Yes, the Doctor dying in his TARDIS includes a literal mirror shot – his face against the glass floor at a crucial moment of grace – but that’s not the most interesting mirror here. The more interesting one, of course, is the Voice Interface.

As we’ve pointed out, Let’s Kill Hitler was produced after The Girl Who Waited and The God Complex. In the former, we got a mysterious white light called “The Interface” through which Amy Pond could communicate with the Two Streams Facility. In the latter, we got another cameo by Caitlin Blackwood, who plays Amelia Pond as a child. So why not bring them together in Let’s Kill Hitler and create additional payoffs down the road?

But that is just a matter of simple cleverness. Here, the Voice Interface is more than just foreshadowing (though the repetition of “You will be dead in 32 minutes” certainly qualifies as foreshadowing). No, what’s far more interesting here is how the Voice Interface functions as a mirror to the Doctor. Notice that the first appearance it takes on is that of the Doctor himself. “No no no, give me someone I like!” he complains. The Voice Interface cycles through images of Rose Tyler, Martha Jones, and Donna Noble. Each of these the Doctor identifies as representing his own personal guilt. Which demonstrates that even when the Voice Interface is taking on a persona other than the Doctor’s there’s still a psychic (psychological) resonance to the Doctor himself. It’s a way of reflecting his inner emotional reality, and specifically the one he’s trying to repress.

I find it interesting, then, that when he gets Amelia for his Voice Interface, she’s still rather uncompromising with him. She refuses to give him solace, is almost aggressive in repeating that he’ll be dead in 32 minutes, and doesn’t even crack a smile. If she’s really a mirror, of course (and look, she’s standing in front of a roundel mirror overlaid upon an X motif) this makes perfect sense – little Amelia wouldn’t behave like that at all, whereas the Doctor’s self-hatred certainly would. And yet there is a moment of grace at the end of all this. Eventually, the Doctor stops bargaining with the Voice Interface, and begs for something for the pain. He stops speaking, stops moving, just lying on the glass floor of the TARDIS, his waxy face gauzily reflected… it is as if he’s given up, and that’s when it comes: “Fish Fingers and Custard.” This is his moment of grace.

We should remark that “grace” has already been invoked in this episode – near the beginning, the Doctor is blaming Mels for shooting his TARDIS, and she says it’s his fault for lying about them being in a state of “temporal grace.” A call back to the Classic Who story The Hand of Fear, certainly, which features another shapeshifter and helps to highlight the importance of “hand” imagery in this story, but also, just on its own, this is very much a story about mercy and grace. They are not the same – mercy is the reprieve of a deserved punishment, while grace is the reception of an undeserved boon and most typically is understood as the beneficence of The Divine upon death, that moment of letting go that everyone will experience.

So what, exactly, is “divine” about Fish Fingers and Custard? Most obviously, it’s an emotional invocation – the moment in their first meeting when Amelia and the Doctor finally bonded. It’s this moment that Amy swore upon when convincing the Doctor to trust her in The Impossible Astronaut. It’s a moment of regeneration. And finally, it’s certainly a moment of silliness, of a completely strange and unexpected synthesis of two parts of space and time that should never have come together, which is practically the ethos of Doctor Who as a television show.

There are two lines of thought on Fish Fingers and Custard that resonate for me in this context. First, for the Doctor, it pulls up the exact memory he needs to keep in mind in order to win the day. Previously his interactions with Melody were confrontational, even judgmental – he doubts that she’s the “best mate” of Amy and Rory, chides her for shooting the TARDIS, admonishes her that time travel never goes to plan… and this is not the approach he can take with this woman. No, he needs to remember his ethos in Amy’s Garden, of not taking himself too seriously, of recognizing the value of whimsy, and most importantly of understanding that he needs to place himself as an equal to Melody, not an authority… which plays into another thematic thread in this episode that we’ll get to shortly.

The other thing about Fish Fingers and Custard is that it represents “integration.” Sometimes the “union of opposites” is not about opposites at all, but about two things that really don’t have much in common. Moreso, though, it’s about recognizing that there’s a time and a place for everything, that there’s nothing in the human condition that can excised from our lives. In terms of this story, the “negative” aspect of humanity that the Doctor has to overcome and yet integrate is judgment – which must be transferred from Melody to the Tesselector. For the Doctor is alchemical, and hermetic, and quicksilver as the alchemy of the hermetic – he must hold up the mirror of judgment to the Judge, as represented by the Tesselector.

The other thing about Fish Fingers and Custard is that it represents “integration.” Sometimes the “union of opposites” is not about opposites at all, but about two things that really don’t have much in common. Moreso, though, it’s about recognizing that there’s a time and a place for everything, that there’s nothing in the human condition that can excised from our lives. In terms of this story, the “negative” aspect of humanity that the Doctor has to overcome and yet integrate is judgment – which must be transferred from Melody to the Tesselector. For the Doctor is alchemical, and hermetic, and quicksilver as the alchemy of the hermetic – he must hold up the mirror of judgment to the Judge, as represented by the Tesselector.

This notion of union is also expressed symbolically after the Doctor receives his moment of grace. When he returns to action, he’s wearing his tails. An outfit that unifies black and white. An outfit that he last wore at a wedding, which marks the union of two people. And he appears in this outfit while standing betwixt twinned symbols of the Circle in the Square – with the round St John’s Ambulance seal in the door panel of the TARDIS foregrounded, and the encircled swastika swamped in red in the background. The union of Red and Blue is much like the union of opposites – one is cool, one is warm, and of course in the opening scene we got a similar juxtaposition with the TARDIS and the Red Corvette. (The swastika, by the way, divorced from its appropriation by fascists, is an ancient symbol that can mean the cycle of birth and death, the myriad of totality, perpetual motion, eternal life, and auspiciousness in general.)

One last thing about the Doctor’s transformation into a veritable Fred Astaire – his sonic cane. When it opens it, the end looks like a jewel in a lotus. And so it’s kind of like a spiritual awakening for the Doctor – he has to stop focusing on his own guilt and self-hatred, which is ultimately borne of ego, and selflessly tend to the people he loves. His resurrection, ironically, comes only when he has demonstrated complete selflessness of his own accord.

The Tesselector

The most striking mirror of the episode is undoubtedly the Tesselector. In this shot from inside the Hotel Adlon restaurant, the mirror that River’s using is literally replaced by a robot duplicate of her mother, who then proceeds to “cast judgment” on her. Considering how much certain critics decried Let’s Kill Hitler for not advancing the cause of tragedy porn (as if having Amy wallow in grief over her lost daughter makes for anything new in the way of television) and finding Amy’s emotional reactions to be rather muted, this seems like the perfect recognition on the part of the show that this was rather intentional. For most of the second half of the story, we see a completely emotionally blank Amy Pond wandering around, thanks the Tesselector mirror – a reflection of Amy’s emotional shut down in Hitler’s office, actually.

The most striking mirror of the episode is undoubtedly the Tesselector. In this shot from inside the Hotel Adlon restaurant, the mirror that River’s using is literally replaced by a robot duplicate of her mother, who then proceeds to “cast judgment” on her. Considering how much certain critics decried Let’s Kill Hitler for not advancing the cause of tragedy porn (as if having Amy wallow in grief over her lost daughter makes for anything new in the way of television) and finding Amy’s emotional reactions to be rather muted, this seems like the perfect recognition on the part of the show that this was rather intentional. For most of the second half of the story, we see a completely emotionally blank Amy Pond wandering around, thanks the Tesselector mirror – a reflection of Amy’s emotional shut down in Hitler’s office, actually.

One might say that the emotional journeys of Amy and the Doctor are mirrored here. Like the Doctor, Amy (and Rory) actually do respond to Melody primarily as parental figures, most often scolding her. But for Amy there’s another dimension to this, namely that Amy’s own “sacred wounding” is born of abandonment. This is territory that’s very familiar to her, and she’s learned well to repress the consequent emotions as well as possible. Over and over again we see Amy being resigned in the face of abandonment – notably in the twinned shots from The Eleventh Hour and A Good Man Goes To War when the Doctor disappears in his TARDIS, with Amy left behind and only a blurry Rory waiting in the background. As the Tesselector is a mirror, we can actually see it’s “attitude” towards River as a way to create space for Amy’s negative emotions without having them overtake the plot. It’s interesting, then, to consider Amy blaming Melody for the Doctor’s death and giving her daughter “hell” – as if that shining light coming from her mouth was a barrage of verbal abuse.

Lest you think this isn’t in character, it’s important to remember how much Amy has been “monstered” this season, which is primarily a function of juxtaposition. In both The Impossible Astronaut and A Good Man Goes To War, we see Amy point a gun at her daughter, and once she even fires. She becomes a pirate in Black Spot, and nearly causes the death of her husband. She’s unveiled as being a Flesh monster at the end of The Almost People. In future episodes, she’ll turn into a wooden Doll in Night Terrors moments after advocating violence to overcome them, she’ll take on the aspects of the Handbots in Two-Streams as a hardened warrior, and she’ll even don an eyepatch and shoot the Doctor in the head in the season finale.

This isn’t a bad thing, mind you. Part of what Doctor Who is doing in this period is using monsters to describe aspects of being human, aspects that we typically don’t want to admit to having ourselves, but which nonetheless can have value. In this episode, then, the monster – the Tesselector – represents an aspect of humanity that we often castigate: authority and judgment. This is what the Tesselector is actually supposed to do – punish people, but in a sanctioned way. Listen to the rhetoric of the Antibodies within the machine, and then the Captain:

– punish people, but in a sanctioned way. Listen to the rhetoric of the Antibodies within the machine, and then the Captain:

“You are unauthorized.”

“Please cooperate in your officially sanctioned termination.”

“All privileges withdrawn.”

“Time travel has… responsibilities.”

“Give them hell.”

This is the rhetoric of power and authority. Here, then, we finally get the thematic link to Nazi Germany, and to fascism, which is just another system of power and authority and judgment. It’s not a particularly sharp rebuke, true (though it’s interesting how Harriet goes to the Eyeball to evaluate the color of the Tesselector’s target) but it nonetheless gets to grist of it, namely the belief that some people are in a “superior” position to others, a position to judge, to exercise “power over.” (Not for no reason, I think, we get the Reveal that the Silence are a religious order trying to purge the Doctor from existence.) And notice how this also ties into A Good Man Goes to War, and the Doctor’s giddiness at telling Dany Boy to take out the communications array at Demon’s Run and “give them hell.” But it’s also at the root of the trouble Amy and the Doctor have in their relationship to Melody, before she figures out who she really. They both take on positions of authority – Amy as the parent, the Doctor as a technocrat – and try to deny Melody her own agency.

Most beautifully, Amy shuts down the Tesselector in much the same way she resolved the problem of The Beast Below. In that episode, she took Liz X by the wrist and forced her to press the “Abdicate” button, to let go of power, and particularly “power-over.” Here, she gets the Tesselector to turn on itself by deactivating all the wrist bracelets that give people “privileges” in the face of authority. She removes all privilege, starting with her own. Yes, she still has privilege – she’s white, British, traveling with the Doctor, etc. – but just as a philosophical position, the revocation of privilege to bring mercy to her daughter is something that just makes me beam.

The Only Water in the Forest

Before I get to the conclusion of this piece, I just want to make a quick digression and point out the plethora of abstract symbolism that we get to play with here. Particularly striking are the X motifs in the wheat field and with the pair of flowers carefully arranged in the Hotel Adlon after Melody has acquired her new outfit. (The X motif also plays against the use of the swastika in this episode.) Anyways, I find these two shots of particular interest because they’re both using “nature” to express a very abstract symbol. And I think it’s deliberate, because within the triptych of images of Melody being released from the principal’s office and eventually jail (the latter of which has a lovely shot of a “hatch” that harkens back to, yes, A Good Man Goes to War, and the reveal of Madame Kovarian looking through a hatch just before Amy’s baby turns to milk) there are some interesting signs on the wall – one an admonishment to “break the silence” when it comes to bullying (hmm, power-over) and another about a “nature trail.” Here, the “nature trail” is in the form of an X.

Before I get to the conclusion of this piece, I just want to make a quick digression and point out the plethora of abstract symbolism that we get to play with here. Particularly striking are the X motifs in the wheat field and with the pair of flowers carefully arranged in the Hotel Adlon after Melody has acquired her new outfit. (The X motif also plays against the use of the swastika in this episode.) Anyways, I find these two shots of particular interest because they’re both using “nature” to express a very abstract symbol. And I think it’s deliberate, because within the triptych of images of Melody being released from the principal’s office and eventually jail (the latter of which has a lovely shot of a “hatch” that harkens back to, yes, A Good Man Goes to War, and the reveal of Madame Kovarian looking through a hatch just before Amy’s baby turns to milk) there are some interesting signs on the wall – one an admonishment to “break the silence” when it comes to bullying (hmm, power-over) and another about a “nature trail.” Here, the “nature trail” is in the form of an X.

As with so much in alchemy, the main point of the X is to suggest some kind of integration. A synthesis. Perhaps, even, a dialectic. But I think it’s also there to signify or mark some kind of “cross over.”

DOCTOR: “Well, at least I’m not a time-travelling shape-shifting robot operated by miniaturised cross people.”

No, not that kind of crossover! No, I mean how the paths of Melody and her parents and the Doctor all cross over each other. They don’t run like train tracks. More like knots. And when two things cross each other, both are irrevocably changed. They become more alike, but also more complicated. Bits of ourselves get lodged in other people, and bits of other people get lodged in ourselves.

Which rather gets back to the Ultimate Question in this show: Who Are You? The oldest question in the universe, hidden in plain sight.

DOCTOR: I’d ask you who you think you are, but I think the answer is pretty obvious. So, who do you think I am? The woman who killed the Doctor. Sounds like you’ve got my biography in there.

But just as this is a story about who the Doctor is, and who Amy has to be (both shed their authority), it’s also a story of Melody becoming River. And yeah, sure, there’s so much going on in Let’s Kill Hitler that is kind of gets short shrift, but it isn’t devoid of development, either. After her “broken table” resurrection, she jumps outside and confronts a group of Nazis, deliberately provoking them with a statement of morality: “Well, I was on my way to this gay Gypsy Bar-Mitzvah for the disabled, when I thought gosh, the Third Reich’s a bit rubbish. I think I’ll kill the Fuhrer. Who’s with me?” She hasn’t killed Hitler, of course – no, she thinks she’s killed the Doctor, and she’s reveling in it. This line pretty much confirms that Melody actually has a moral compass, and believes that as a “warrior” she’s done a good thing in taking out the man who “understands every kind of warfare,” and whose exercising of authority during her encounter with him only confirms that he’s the “Hitler” deserving of punishment and justice, despite her parents’ beliefs.

And yet, ironically, when she gets to the Hotel Adlon restaurant, she ends up donning the official jacket and cap of an SS officer. She too, like the Doctor and Amy, has fallen into the trap of judgment and authority.

So what does it take for Melody to change “who she is” in such a short amount of time? Or, conversely, to shed the exterior trappings of who she thinks she is? It may be the most frustrating aspect of the episode, that so much of this process is shown in bits and snippets, leaving us to piece together the pieces into something resembling coherency. Oh well. Not a problem for me, given I’m inclined to in-depth longform close readings anyways, but I can understand where a lot of people are coming from. All that said, I do think all the pieces are there to put together.

The most striking thing, I think, is how much of Melody’s journey is portrayed using iconography with mythic or religious overtones. Earlier we discussed how her regeneration took place on a broken table, evoking the Narnia story which itself is a religious allegory. When the Tesselector finally “gives her hell” she’s literally a depicted as experiencing Hell, an agony of fiery torment. (Of course, given she’s a Pond—or a River—the fact she’s burning makes for a peculiar alchemy: once again, the union of opposites.) The poison she used on the Doctor was from “the Judas Tree” – Judas, of course, was the apostle who betrayed Jesus, and with a kiss.

The most striking thing, I think, is how much of Melody’s journey is portrayed using iconography with mythic or religious overtones. Earlier we discussed how her regeneration took place on a broken table, evoking the Narnia story which itself is a religious allegory. When the Tesselector finally “gives her hell” she’s literally a depicted as experiencing Hell, an agony of fiery torment. (Of course, given she’s a Pond—or a River—the fact she’s burning makes for a peculiar alchemy: once again, the union of opposites.) The poison she used on the Doctor was from “the Judas Tree” – Judas, of course, was the apostle who betrayed Jesus, and with a kiss.

Anyways, to be relieved of this burning judgment could properly be called a Mercy. That she is deserving of punishment – she’s attempted murder – seems like something even she might believe, given how she was raised by Amy, who loves the Doctor. Its cessation, therefore, especially in light of the religious overtones of its presentation, I’m perfectly happy to cast as Mercy, with a capital M. But this isn’t enough to help Melody see the light. The next step is actually requires stepping into the opportunity to be the one who delivers salvation.

It’s not, I think, the scene where the Doctor flails on the floor while Melody watches, saying she’s impressed, while getting ever more curious about River Song. And we don’t actually get to see the moment where she decides to go ahead and save her parents. What we see, instead, are the after-effects of her choice.

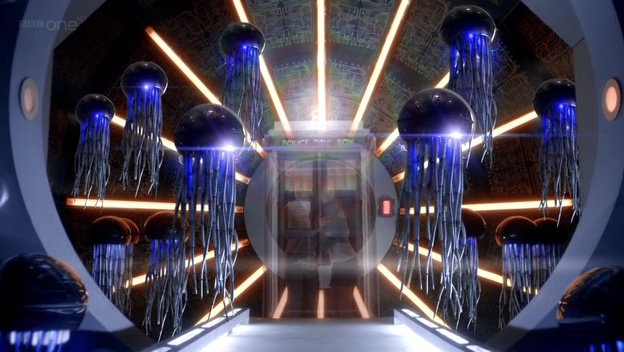

Those after-effects are two-fold. First, we get a shot of the TARDIS materializing around Amy and Rory as they face certain death – this is their literal salvation. It’s a shot that’s deliciously visual and metaphoric. We get one of those beautiful images where the TARDIS is presented a religious object – a veritable Holy Ghost. A silvery shimmering square appears halo around Amy and Rory, while golden rays beam out from the convergence. For it is a convergence. It’s materializing inside an “eyeball” and so we get not a Circle in the Square, but the reverse, the Square in the Circle — not the Divine within the Material body, but the Material Body within the Divine. Which, let’s take a step back from that. Material action within a field of divinity – and in particular, a material rectification of that “divine judgment.” (Also, I love how the Antibodies “float” in this scene, like the “floaties” one gets in one’s eye, the loose detritus of one’s retina. Plus, they look like jellyfish, and there’s a species of jellyfish that’s functionally immortal – rather than aging, it reverts to its immature polyp stage and begins its life cycle anew.) And then there’s the metaphor of Melody finally getting “into her mother’s head,” given the Tesselector has taken on Amy’s appearance.

Those after-effects are two-fold. First, we get a shot of the TARDIS materializing around Amy and Rory as they face certain death – this is their literal salvation. It’s a shot that’s deliciously visual and metaphoric. We get one of those beautiful images where the TARDIS is presented a religious object – a veritable Holy Ghost. A silvery shimmering square appears halo around Amy and Rory, while golden rays beam out from the convergence. For it is a convergence. It’s materializing inside an “eyeball” and so we get not a Circle in the Square, but the reverse, the Square in the Circle — not the Divine within the Material body, but the Material Body within the Divine. Which, let’s take a step back from that. Material action within a field of divinity – and in particular, a material rectification of that “divine judgment.” (Also, I love how the Antibodies “float” in this scene, like the “floaties” one gets in one’s eye, the loose detritus of one’s retina. Plus, they look like jellyfish, and there’s a species of jellyfish that’s functionally immortal – rather than aging, it reverts to its immature polyp stage and begins its life cycle anew.) And then there’s the metaphor of Melody finally getting “into her mother’s head,” given the Tesselector has taken on Amy’s appearance.

This shot is immediately followed by Melody’s appearance in the TARDIS, where she is visibly shaken by what she’s just learned about herself – she is the “child of the TARDIS,” which, remember, has just been depicted as a holy object. And she herself has just delivered salvation. She might as well realize that she’s a Child of the Goddess – for actually, she is. And just as she’s gotten into her mother’s head,  her other mother has just gotten into hers – Melody can now “fly” her, which is an apt way to describe an Ascension.

her other mother has just gotten into hers – Melody can now “fly” her, which is an apt way to describe an Ascension.

When we return to the Hotel Adlon, the Doctor dies. But not before whispering something in Melody’s ear, a message for River Song. It doesn’t matter what the message is – it sounds important and personal and meaningful to Melody, enough so for her curiosity to follow up and ask her mother who River is. Amy, now that she’s mastered the Tesselector, simply uses it as a mirror. And we get this beautiful shot of the Tesselector turning into River, a River who has a halo around her. Melody finally gets the answer to her question, to oldest question in the Universe – Who Are You? – and realizes that she is not bespoke, not a psychopath, and neither mundane nor profane, but holy and sacred. Which every daughter could stand to learn from her mother, oh Persephone, oh Demeter.

It is with this understanding that River is now able to confer not just Mercy, but Grace – that boon which is neither deserved nor expected (hence the necessity of giving up or letting go). She kneels before the dead god and performs a Laying On of Hands. Golden light swirls throughout the cathedral as she bestows the Kiss of Life, a reversal of her earlier kiss. And it is an act of Self Sacrifice, which we aren’t meant to take literally – for in mythology, self-sacrifice is simply a vehicle for Ego Death, which bestows union with the Universe.

In the denouement, everything comes full circle. River awakens under the World Tree, which symbolizes the connection of Above and Below, Past and Future, to the Here and Now. This is coupled with a very interesting directorial choice – Amy and Rory looking into the camera as they address their daughter. Which rather suggests that we ourselves are the Water in the Forest, if we can only remember, every one a drop of rain flowing to the ocean.

And now the narrative substitution is complete. This was never just a romp.

And it wasn’t even a story about Grace. Nor, indeed, is it necessarily a story about River.

It can be a story about you… if you dare.

February 2, 2016 @ 12:48 pm

Welcome back Jane, and with a fantastic overview of LKH. Thanks for your totally enjoyable close reading/reconstruction. I love your suggestion that it is in fact the Doctor whom Mels considers to be the ‘Hitler’ worthy of assassination.

A story about me if I dare? Okay let’s see…

Once again your observations, filtered through my own esoteric knowledge, suggest to me links to Tarot imagery. The Tesselector as Judgement or Justice, Amy and Rory as the Lovers with the Doctor as the presiding angel of the image which also suggest its mirror, the Devil card with the Doctor as Devil and Amy and Rory as chained supplicants. Thus the dual nature of the Doctor’s relationships is revealed.

You link Amy with Demeter, who is represented in Tarot as the Empress. Take a look at the Rider Waite deck depiction of the card. Demeter sits in a field of corn on a throne (the chair agenda!) While a river(!) flows toward her from the trees behind. She wears a crown of twelve stars, traditionally signifying the zodiac but in this case I feel Amy’s growing intellectual understanding of the universe. The Empress is card 3 of the major arcana (foreshadowing The Power of Three?).

I’m struck by the number of vehicles in this episode, the cars in the wheat field, the motorbike, the TARDIS and the Tesselector itself. For me the TARDIS is always the Chariot (in the Waite deck shown pulled by sphinxes, traditional askers of riddles, “Who Are You?”)

Coincidently (if there is such a thing) I’ve been considering revisiting series 6 myself. Bearing in mind your observations on the production schedule iliciting foreshadowing and so forth do you have a suggestion for an order to watch the episodes in?

February 2, 2016 @ 10:51 pm

I really think the broadcast order is for the best when it comes to a rewatch. Just bear in mind that the Moffat episodes are the “connective tissue” holding together the other episodes. Stories like Black Spot and TGWW really deserve to be understood in context of the larger threads around them; it really behooves us to consider the events therein as metaphors for the issues surrounding them.

February 2, 2016 @ 4:08 pm

A wonderful read, Jane, as ever. Not an episode I’ve ever been terribly keen on; but I’m considering reevaluating my position after that analysis. Are we back to Tuesdays as your regular slot, then?

February 2, 2016 @ 10:52 pm

Yup, back to Tuesdays. Hoping to get another Lost Exegesis in next week. 🙂

February 3, 2016 @ 12:39 am

Put me down as another reader who’s reevaluating his take on this episode. Your take on it has revealed a lot to me that I missed.

February 4, 2016 @ 3:15 am

Thank you! Even though this episode has all sorts of issues, I really, really enjoyed it when I first watched it and I think this essay highlights why. I certainly didn’t notice all of the symbolism throughout, but it is obviously dense with story even if you aren’t looking for the symbolism itself. Even when the density lead to it not making a ton of sense, I still liked the overstuffedness of it. (This is unlike most science fiction that is overstuffed, where they just spend most of the time explaining things.)

Also, that’s an excellent definition of mercy vs. grace. They far too often – especially in evangelical Christianity – are confused for each other.

February 6, 2016 @ 5:57 pm

If you ever write another piece on this, you can call it “They Keep Killing Hitler.”

March 24, 2016 @ 4:36 pm

This was a beautiful read. Thank you. I’ve always loved your take on Doctor Who and visual symbolism.

Funny thing, I found this after noticing all the golden halos around River Song in The Husbands Of River Song. It seems the motifs of divinity & redemption is literally echoed in that episode. Which I thought was a fitting ‘last’ episode for her. I would love to read you take on it if you ever have the inclination.

Thanks for all your wonderful work!