Lost Exegesis (Pilot Part 2)

One would think, given they pretty much share the same title, that Pilot Part 1 and Pilot Part 2 would be rather similar, that the two parts would fit together as a functional whole. It’s true that both episodes were shot as part of the same production block. However, the two parts aired a week apart. Which was probably wise, for Pilot Part 2 is a very different beast compared to Pilot Part 1.

One would think, given they pretty much share the same title, that Pilot Part 1 and Pilot Part 2 would be rather similar, that the two parts would fit together as a functional whole. It’s true that both episodes were shot as part of the same production block. However, the two parts aired a week apart. Which was probably wise, for Pilot Part 2 is a very different beast compared to Pilot Part 1.

And one might wonder if the two parts had a different director, but they did not; JJ Abrams helmed both parts. Yet they have a very different feel from each other. Pilot Part 2 is rather visually distinct from its predecessor, as all of it is terribly bright; there’s an awful lot of sunlight. The first episode, on the other hand, had moments of “day becoming night,” scenes dominated by cloud cover and shadow, and even one shot at night. Pilot Part 2, on the other hand, is terribly bright; there’s an awful lot of sunlight. But then, Part 1 covers Day One on the Island, Night One, and the beginning of Day Two. All of Part 2 happens during Day Two.

While much of that could be attributed to the vagaries of the weather, we cannot say the same about the episodes’ structures. The structure of Part 1, as we noted in the previous essay, was split in two. The first half ran for twenty straight minutes, without commercial interruption. It had several very long scenes – Jack running out of the jungle and playing the hero while the remnants of the plane exploded. Then a long montage of the wreckage, and people milling about, accompanied by a morose musical score. A few short scenes serve to very briefly introduce a few of the other characters, but there’s some long conversations between Kate and Jack (as she stitches up his wound, and as they talk about the plane crash by a campfire) before the Monster brought that half to a climax. After Jack’s Flashback, the rest of the episode is almost entirely concerned with a trek to the cockpit to retrieve the airplane’s transceiver, and another attack by the monster. The whole episode is largely focused on Jack, secondarily on Kate and Charlie, and is very much in the mold of an action-adventure.

Pilot Part 2, on the other hand, consists of 27 vignettes that eventually feature all of the ensemble cast. The episode runs only 40 minutes. The final scene is five minutes long, and each of the two flashback scenes run about three minutes. As such, most scenes barely last a minute. This gives the episode a very different pace.

And yet it’s not nearly as propulsive as Pilot Part 1, for most of the vignettes are very languorous on their own. Sure, there are a few action sequences – both Flashbacks are on the crashing plane, and there’s the charge of the polar bear – but these are not the focus of the episode. No, this episode gets to do the heavy lifting of introducing us to all of LOST’s characters, primarily through dialogue (as opposed to, but not entirely without, plot). And so the episode makes the brave but necessary decision to largely sideline Jack, sticking him on the beach while six other characters form an away team to hike up a mountain, led by Kate and Sayid.

All that said, there’s still quite a that this episode shares deeply in common with Pilot Part 1, such that they can be easily identified as being kith and kin to each other.

Automictic Parthenogenesis

In the last installment of the Exegesis, we noted several instances where the dialogue had a “mirror-twin” aesthetic to it, through the use of repetition and reversal. Here, that aesthetic is ramped up. Every single one of the 27 vignettes partakes of it in some form or fashion. Some of the mirror-twinning continues through dialogue. Sometimes it’s visual, or thematic. Sometimes it’s both.

In the last installment of the Exegesis, we noted several instances where the dialogue had a “mirror-twin” aesthetic to it, through the use of repetition and reversal. Here, that aesthetic is ramped up. Every single one of the 27 vignettes partakes of it in some form or fashion. Some of the mirror-twinning continues through dialogue. Sometimes it’s visual, or thematic. Sometimes it’s both.

Dialogue-based twinning is actually much more subtle, because the actors have their own voices, their own delivery, and it goes by so quick it’s often over in a flash. Looking at transcripts, however, the structure of the dialogue becomes much more apparent. In the first two lines of the very first scene, for example, we get a twinning of “anything”:

CHARLIE: Anything?

JACK: You keep asking if there’s anything.

Likewise, the final two lines of the scene has that same kind of beat:

CHARLIE: Every trek needs a coward.

KATE: You’re not a coward.

But of course, such dialogue isn’t in service to an aesthetic. The scene is actually about the fact that Jack isn’t getting anything from the transceiver, which is plot based, and then about Kate not understanding why Charlie even came on the trek to the cockpit at all, as his subsequent Flashback shows: he went to get his heroin. And now we know a lot more about Charlie than we did before.

Likewise, when our heroes hit the beach and encounter a fight among the survivors, the point is to start drawing out some characterization. We see that where Michael is ineffective at peacemaking, whereas Jack gets the fight stopped; Sawyer and Sayid have no respect for each other, and indeed seem to be blinded by their initial prejudices. And again, there’s a great deal of mirroring in the dialogue that might otherwise go unnoticed:

MICHAEL: Hey guys. Come on, man. Hey.

JACK: Hey. Break it up. Break it up! Come on! That’s it! It’s over! That’s it!

Not only does Jack repeat “break it up” and “that’s it,” he also repeats Michael’s “hey” and “come on.”

SAWYER: Son of a bitch!

SAYID: I’m sick of this redneck!

SAWYER: You want some more of me, boy?

SAYID: Tell everyone what you told me! Tell them that I crashed the plane! Go on! Tell them I made the plane crash!

SAWYER: The shoe fits, buddy!

JACK: What is going on?

SAYID: Ibn al-kalb!

JACK: What’s going on?

This is even better. Sayid insists twice that Sawyer “tell them” he made the plane crash. Jack repeats his question about what’s “going on.” And, most cutely, Sawyer’s “son of a bitch” is twinned by Sayid’s “Ibn al-Kalb,” basically the same phrase, just in Arabic. And sure, it’s easy to miss stuff like this in the heat of the moment – everyone’s yelling and talking over each other.

This conceit is present even in relatively languid scenes, however. Immediately after the fight, Sayid and Hurley head over to a singular tree (an axis mundi?) on the beach and commiserate peacefully. It too is twinned:

HURLEY: Chain-smoking jackass.

SAYID: Some people have problems.

HURLEY: Some people have problems? Us. Him. You’re okay. I like you.

SAYID: You’re okay, too.

This scene has a great reversal in it, by the way. Hurley asks how Sayid knows about things like transceivers, and discovers that Sayid fought in the Gulf War. Then he asks if Sayid was in the Air Force, or perhaps the Army. Sayid corrects this assumption – he fought with the Republican Guard; he’s an Iraqi. And it’s a great beat: Hurley now has to recognize that he’s just made friends with somebody who was “the enemy” in that conflict. And we do, too—Sayid definitely has been portrayed as one of the “good guys” right off the bat. Neatly, the underlying conceit of this is likewise reflected in the dialogue: “Us. Him.” For it’s the Us/Them mentality that’s at the heart of war culture. On a large scale, then, the alchemical principle of the “union of opposites” would also point the way towards peace. Material social progress, indeed.

As mentioned, other mirror-twinnings rely on visual juxtapositions. Case in point, the third scene of the episode, where Shannon and Claire finally meet. We open with a shot of Shannon lying on her back, her flat belly exposed to the sun. She’s juxtaposed with Claire and her great pregnant belly, who she says, “I used to have a stomach” (as if having no belly is somehow great than having a big one), before she goes on about how she hasn’t felt the baby move, and doesn’t know the baby’s gender. As this scene progresses, Claire removes her blouse, making her belly more exposed. Shannon, on the other hand, turns over, hiding her stomach… as if they were enacting the alchemical principle of equivalent exchange.

This is immediately followed by a shot of Jin collecting sea urchins, from which he makes sushi. In another visual juxtaposition, we see him offer the raw fish to Hurley, he of the big belly, but Hurley refuses, twice. The other person offered sushi is Claire, sitting in a pair of airline chairs (she’s sitting for two, natch.) Claire also refuses, but the second time she concedes… and then the baby kicks, and Claire realizes her babe is a boy.

This is immediately followed by a shot of Jin collecting sea urchins, from which he makes sushi. In another visual juxtaposition, we see him offer the raw fish to Hurley, he of the big belly, but Hurley refuses, twice. The other person offered sushi is Claire, sitting in a pair of airline chairs (she’s sitting for two, natch.) Claire also refuses, but the second time she concedes… and then the baby kicks, and Claire realizes her babe is a boy.

I find it interesting how the chairs match the colors of Hurley’s shirt. Behind Hurley, we have the ocean — water is a reflective surface. In Claire’s shot, we can tell that the undersid of Jin’s tray is, yes, reflective.

All implications of The Chair Agenda aside (looks like a resurrection to me), there’s at least a certain artistry to how all these scenes are composed, shot, and edited. Looking at the final production script for the Pilot episodes, for example, we can see that certain scenes have been rearranged. The aforementioned shot with Shannon and Claire, for example, was supposed to immediately follow the reveal of the Pilot up in the trees… but as the first shot of Pilot Part 2, given the choice to cliffhanger on the Pilot reveal, it makes sense they’d start with our trekkers in the jungle, and Charlie’s flashback, before cutting to Shannon and Claire after the commercial break.

Another such change at the production level now comes right at the structural midpoint of Pilot Part 2, the 14th scene of the 27. It’s a rather strange scene—one might be tempted to call it three very short scenes, or better yet, a triptych. We open with Charlie at the edge of the jungle, getting a fix of heroin. We then cut to Jack asking Hurley to help him find antibiotics. Then we cut back to Charlie now enjoyed the effect of his fix. The whole sequence takes but 40 seconds. But the thing that binds this triptych together is thematic: drugs. (Funny thing, Jack is called a “hero” by Sawyer, while Charlie is a heroin addict. Well, I thought it was funny.)

Another such change at the production level now comes right at the structural midpoint of Pilot Part 2, the 14th scene of the 27. It’s a rather strange scene—one might be tempted to call it three very short scenes, or better yet, a triptych. We open with Charlie at the edge of the jungle, getting a fix of heroin. We then cut to Jack asking Hurley to help him find antibiotics. Then we cut back to Charlie now enjoyed the effect of his fix. The whole sequence takes but 40 seconds. But the thing that binds this triptych together is thematic: drugs. (Funny thing, Jack is called a “hero” by Sawyer, while Charlie is a heroin addict. Well, I thought it was funny.)

This isn’t how these shots are ordered in the production script. They don’t fall at this place in the narrative, and furthermore, the shot of Charlie taking drugs isn’t even in two halves. At the level of editing, then, what we have here is a case of Jack’s scene being spliced into Charlie’s scene; the entire ensemble is then spliced into the structural center of the episode.

Mirror-Twinning

The aesthetic governing LOST, as I’ve said before, is one of “mirror-twinning.” When you hold up a mirror to something, effect is two-fold. On the one hand, the reflection creates a second image, a “twin.” On the other hand, this twin will be reversed in some respect. At a thematic level, then, the “twinning” of Jack and Charlie (through their respective searches for drugs) reveals a polarity: Jack is a hero, while Charlie is a heroin addict, a coward.

This conceit lends new meaning to the appearance of the Polar Bear in the back half of the episode. Yes, it’s a reversal of polarity that a polar bear is found on a tropical island. And sure, the word “polar” is in “polarity.” The common etymology in those word is, of course, “pole,” point to the axis mundi, center that marks the connection of Above and Below, Past and Future, to the Here and Now, and the principle by which the union of opposites occur.

This sort of connectivity implicit in the conceit of Mirror-Twinning is nicely symbolized by the handcuffs found by Walt in the jungle at the beginning of the episode. They’re silver, like a mirror. They have a left and a right side, the principle of reversal. But they’re chained together, as implied by the axis mundi.

This sort of connectivity implicit in the conceit of Mirror-Twinning is nicely symbolized by the handcuffs found by Walt in the jungle at the beginning of the episode. They’re silver, like a mirror. They have a left and a right side, the principle of reversal. But they’re chained together, as implied by the axis mundi.

And yet they’re not presented as symbolic. Instead they are used dramatically, in a variety of ways. First, they’re foreboding: when Walt hands the cuffs to Michael, it’s clear from Michael’s reaction that the implication that anyone on the plane would be wearing handcuffs, and has actually escaped from them, makes the beach potentially dangerous, notwithstanding the presence of a Monster in the jungle. Later, as the presence of handcuffs becomes known, they present a mystery to the Losties—who was the Prisoner? Notably, this is a mystery for the audience as well. And, just like the bottles of booze we saw Jack pull out of his pocket at the very beginning of Pilot Part 1, we get an answer to the mystery right away—Kate. And just like Sayid, we’ve gotten to know enough about her to root for her, before we learn something that might otherwise cast her as “a bad guy.”

But what is the mirror-twin to a pair of handcuffs? To this we add the Knife, another silvery reflective surface. This shot comes in the scene where Michael mopes about alienating his son Walt, while Jack is rummaging through baggage claim looking for something that might suffice for surgery on the Marshal. That we get a close-up on the Knife has ostensibly nothing to with their subsequent interaction, which hinges on Jack’s reveal that he saw a dog in the jungle. The effect on Michael is profound—now he has hope that he might be able to win over Walt. Michael’s attitude, in other words, has been reversed. The knife functions symbolically as a mirror here.

However, unlike handcuffs, which bind, a knife separates, cleaves. You can split something in two with a knife. Each slice doubles the numbers. Immediately following the knife scene, we switch to a shot of the Backgammon set. This particular set has a doubling cube. It’s used for gambling, doubling the bet on the game.

And so it is with Pilot Part 2. The number of pilot episodes has doubled. The number of flashbacks have doubled. The size of the away team has doubled. This doubling, however, it is not like creating a mirror image. It’s more like giving birth. And in this case, the second episode isn’t a perfect clone of the first. It’s a half-clone. Automictic Parthenogenesis.

Intermission (Green Lantern / Flash : Faster Friends)

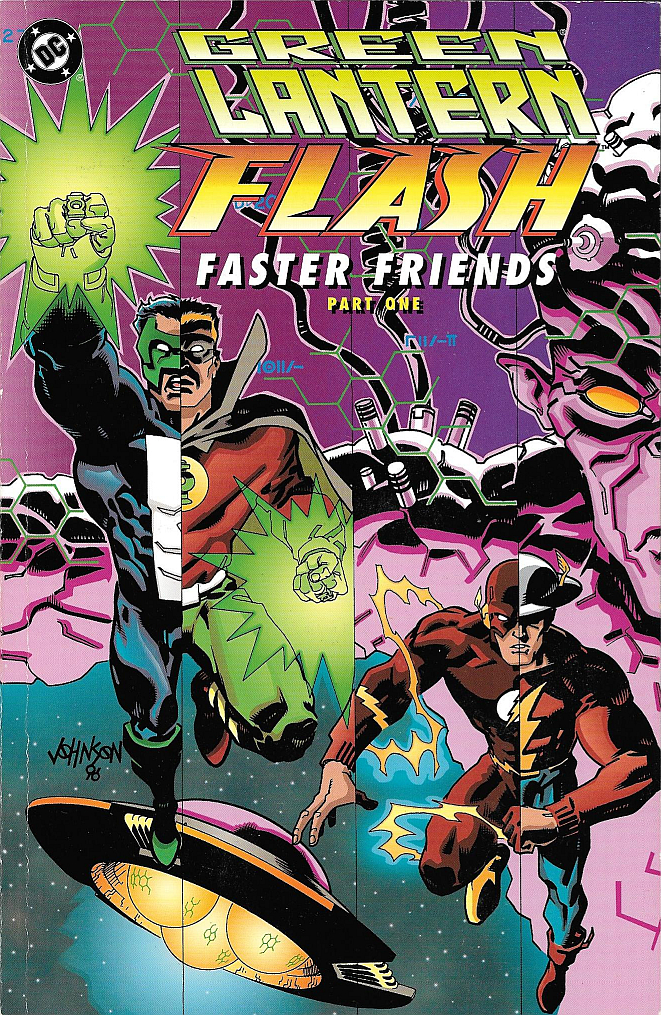

Quite often in the course of LOST we get explicit references to other texts. As the Lost Exegesis covers such episodes, rather than jumping straight into the second portion of the essay that dispenses with the pretense that we don’t know what’s going to happen (and hence where spoilers will abound), there may be an intermission to reflect on the episode’s intertextuality. This first “intermission” (an inter-textuality-mission) will take a look at the comic book Walt was reading on the beach, the one in Spanish that he couldn’t understand… the one with the polar bear. It’s a Green Lantern / Flash crossover comic called “Faster Friends.” Thankfully, I have an English translation.

Quite often in the course of LOST we get explicit references to other texts. As the Lost Exegesis covers such episodes, rather than jumping straight into the second portion of the essay that dispenses with the pretense that we don’t know what’s going to happen (and hence where spoilers will abound), there may be an intermission to reflect on the episode’s intertextuality. This first “intermission” (an inter-textuality-mission) will take a look at the comic book Walt was reading on the beach, the one in Spanish that he couldn’t understand… the one with the polar bear. It’s a Green Lantern / Flash crossover comic called “Faster Friends.” Thankfully, I have an English translation.

This is a story told (like LOST’s pilot episode) in two parts. The first is a Green Lantern comic that shares time with the Flash – here, all the narrational captions are from the perspective of Green Lantern. Likewise, the second part is a Flash comic that shares time with Green Lantern, and again, this time the narrating captions are from the perspective of the Flash. You’d be correct in guessing that I would call this an example of mirror-twinning. Just take a look at that cover, which features both modern-day and golden-age versions of Green Lantern and Flash cleaved together.

Which is entirely appropriate, given there are in fact two Green Lanterns in the story, and two Flashes. Representing Green Lantern, we have Alan Scott (golden age) and Kyle Rayner (contemporary). For the Flash, we have Jay Garrick and the blonde Wally West, respectively.

The story itself is pretty simple. “Alien X” (his actual name is unpronounceable) breaks free from his US Gov’t prison and captures the golden-age heroes, Alan and Jay. Through a shared Flashback, we find out that they captured Alien X back in the early 40s, and, idiotically trusting the military, handed over Alien X, which they now regret: Alien X has since been tortured and subjected to biological experimentation, such that the thousands of years he’d expect to live have been shortened to mere months; he has the alien equivalent of terminal cancer. Jay can sympathize, being similarly afflicted.

Kyle and Wally track them to the North Pole, where Alien X has taken them to retrieve his spaceship (hence the polar bear). And of course there’s a big fight – between the contemporary heroes and the golden-age ones, who are psychically compelled by Alien X. When the jig is up, Alien X triggers a “failsafe” in the spaceship: he dies, but sends out a transmission that invites an alien invasion of a, um, planetary cancer. Think in terms of Doctor Who’s Planet of the Dead.

Given the appearance of the polar bear on the Island coming on the heels of Walt reading this particular comic, are we meant to infer that Walt is psychic? I think we are. He’s our “X” factor.

Given the appearance of the polar bear on the Island coming on the heels of Walt reading this particular comic, are we meant to infer that Walt is psychic? I think we are. He’s our “X” factor.

Getting back to the comics. In Part 2, the invasion proceeds apace, again after a brief Flashback. Back in the present, through some wormhole-portals the mindless aliens pour. All of DC’s superheroes are swamped. To stop the invasion at its source, Wally and Kyle (our contemporary Lantern and Flash) jump through a portal, at the same time, together. In yet another instance of mirror-twinning, they switch bodies, such that Kyle’s consciousness now resides in the body of the Flash, while Wally’s consciousness now resides in the body of the Green Lantern; weirdly and confusingly, they don’t switch outfits. The mixup is only resolved when they converge (thanks to the help of their elders, who didn’t get mixed up because they went through separate portals), and Green Lantern’s body is reunited with his ring.

The plot, by the way, turns into a meditation on Death. The alien creatures that consume planets actually feed their Mother, to keep her from dying. Jay Garrick, who’s thought about the nature of regret (hello, Alien X; also, keeping secrets from his wife), has something to say about it to Mother:

JAY: Listen to me — whatever you are! Believe me, I know what it’s like to have something gnawing away inside of you – waking you up to reality! You fight and fight against it because you don’t want to accept your own mortality.

You’re forced to look at all those around you , great and tiny… the hurt and suffering you’ve caused them over the years, all the times you haven’t been there for them… and you want desperately to say that, in the grand scheme, those little hurts don’t matter.

But they do. Every life counts. No one, no matter how insignificant, deserves to be hurt… or ignored. Not life is worth living without conscience… and without communication. I know that now. And so do you.

The Mother opens up a portal and leaves. Turns out that the Flash was able to create a sympathetic vibration and establish a two-way link of communication with the creature; both Flashes are reasonably sure that Mother got the message. As to Jay’s illness, well, he and Alan travel back to Earth through the same portal (it’s a race, as both think they need to self-sacrifice for each other, and now we know that Green Lantern can fly faster than Flash can run), and as a result Green Lantern’s biology cures Jay. So there’s that.

The Mother opens up a portal and leaves. Turns out that the Flash was able to create a sympathetic vibration and establish a two-way link of communication with the creature; both Flashes are reasonably sure that Mother got the message. As to Jay’s illness, well, he and Alan travel back to Earth through the same portal (it’s a race, as both think they need to self-sacrifice for each other, and now we know that Green Lantern can fly faster than Flash can run), and as a result Green Lantern’s biology cures Jay. So there’s that.

That the plot’s resolution doesn’t depend on violence, but an acceptance of death, well, that’s something I find particularly interesting. Especially the bit where Jay practically invokes what people in the Near Death Experience community call “Life Review.” For a superhero comic, it’s surprisingly circumspect. Reverential, even. The story is ultimately a story about faith, and self-sacrifice, and atonement.

We now return you to your regular programming. Spoilers will abound.

LOST Through the Looking Glass (Pilot Part 2)

SHANNON: It’s… it’s repeating.

SAYID: She’s right.

BOONE: What?

SAYID: It’s a loop. “Iteration”—it’s repeating the same message.

One of the rather interesting things about LOST is its use of language, in particular languages other than English. If we want to talk about LOST as a metaphor for the experience of being “lost,” then certainly one of those ways is being unable to understand what someone else is saying.

In this episode alone we’re exposed to four different languages: Sayid speaks Arabic when he and Sawyer are fighting on the beach; Sun and Jin, of course, speak Korean; Walt finds a comic book that’s in Spanish, and which we now know was actually Hurley’s; and then there’s Danielle Rousseau’s distress call to close out the episode.

But in what’s a miraculous stroke of luck, Shannon just happens to be on the trek, and just happens to know how to speak French, and so she’s able to provide a simulacrum of a transmission, once she gets over her fear of being a failure, of being “worthless.” And so the gist of the message, and its implications, are not lost on the Losties. However, it is fair to ask… was any part of the message lost in translation? Thankfully, in the age of teh interwebz, there are plenty of people who can translate French, and who indeed translated the Frenchwoman’s transmission shortly after the episode was first broadcast.

Si qui que ce soit puisse entendre ceci, ils sont morts. Veuillez nous aider. Je vais essayer d’aller jusqu’au rocher noir. Il les a tués. Il les a tués tous.

If anybody can hear this, they are dead. Please help us. I’ll try to make it to the black rock. It killed them. It killed them all.

Okay, good thing we took a closer look at this! There was something else in there, a reference to “The Black Rock.” Which was a lovely mystery for those attentive fans who paid attention to such things, and which paid off magnificently in the Season One finale when our Losties were brought to a 19th Century tall ship in the middle of the jungle with the name of “The Black Rock.” As Sayid put it in this episode, “Thank you for observing my behavior.” Or, the pseudonymous Mark Wickman said, “Careful observation in the only key to true and complete awareness.” And so we dive deeper into the transmission.

Il est dehors. il est dehors et Brennan a pris les clés. Veuillez nous aider. Ils sont morts. Ils sont tous morts. Aidez-nous. Ils sont morts.

It is outside. It is outside and Brennan took the keys. Please help us. They are dead. They are all dead. Help us. They are dead.

This, as it turns out, is the second transmission. It’s, um, very much different from the first. Which, you know, it really shouldn’t be, if the transmission is being played on a loop. The thing is, though, just like the reference to “The Black Rock” is paid off at season’s end, so too is the invocation of the mysterious “Brennan,” in the Season Five episode This Place Is Death, which charts the events that happened to Danielle Rousseau’s crew sixteen years ago.

Ils sont tous morts. Aidez-nous. Ils sont morts. Si qui que ce soit puisse entendre ceci–… Il est dehors. Veuillez nous aider. Veuillez nous aider!

They are all dead. Help us. They are dead. If anybody can hear this — It is outside. Please help us. Please help us!

The third iteration seems like it’s composed of splices from the first two. Likewise, the fourth:

Si qui que ce soit puisse entendre ceci, je vais essayer d’aller jusqu’au rocher noir. Veuillez nous aider. Ils sont tous morts. Ils sont morts. Il les a tués. Ils les a tués tous. Je vais essayer d’aller jusqu’au rocher noir.

If anybody can hear this, I’ll try to make it to the black rock. Please help us! They are all dead. They are dead. It killed them. It killed them all. I’ll try to make it to the black rock.

Now, one could just say that this is a production error, that they screwed up a bunch of different takes. But given that all these iterations had to be written in the first place, I don’t find this explanation very plausible. One might also say that this is just a bit of trolling on the part of the production, something to mess with people who insist on reading the show so closely. After all, this was touted as a JJ Abrams production, and given his style with Alias, which had plenty of Easter Eggs, it’s not entirely unreasonable. Well, except that tidbits like “The Black Rock” and “Brennan” actually pay off. That isn’t exactly trolling. So I don’t find this explanation very satisfying, either.

Which kind of leaves us with considering that the differences in the iterations are entirely intentional. It all had to be written and translated into French in the first place; not only is it not in fact gibberish, but it actually contains pertinent details; JJ Abrams is known for putting such clues in his text. Intentional makes sense.

The real question is then, “What is the intention?” And to this we can only speculate, for the mystery of the Island was never revealed, and the writers won’t divulge their secrets. Which is all fine and good. But that can’t keep us from speculating. It would help if there was another instance of “iterations” to examine, and as it so happens we already have three now, given that the Flashbacks of Jack, Charlie, and Kate all occurred during the same event: the Crash of Flight 815.

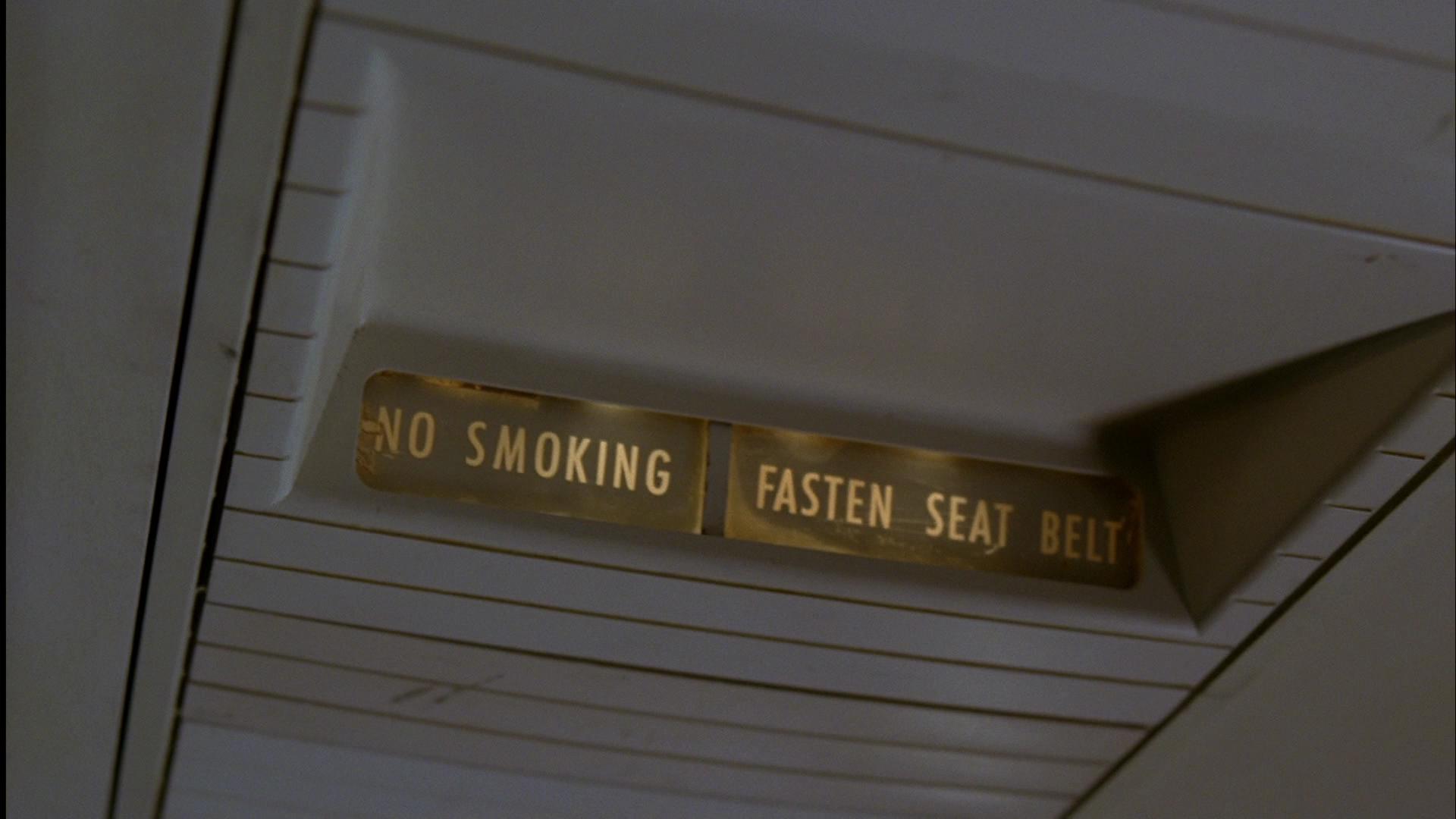

They are, in fact, all remarkably similar, each reflecting the same basic physical reality, that of the plane in the minutes before it crashed. For example, Charlie bumping into Jack, followed by the flight attendants, happens in both Flashbacks, and with the same dialogue. But there’s one thing that’s different in each iteration. In all three, the stewardess Cindy tells people to put on their seatbelts. But the actual spoken line changes:

They are, in fact, all remarkably similar, each reflecting the same basic physical reality, that of the plane in the minutes before it crashed. For example, Charlie bumping into Jack, followed by the flight attendants, happens in both Flashbacks, and with the same dialogue. But there’s one thing that’s different in each iteration. In all three, the stewardess Cindy tells people to put on their seatbelts. But the actual spoken line changes:

JACK’S FB: Ladies and gentleman, the pilot has switched on the “fasten seatbelt” sign. Please return to your seats and fasten your seatbelts.

CHARLIE’S FB: Ladies and gentlemen, the captain has turned on the “fasten seatbelt” sign. Please return to your seats and fasten your seatbelts.

KATE’S FB: Ladies and gentlemen, the captain has switched on the “fasten seatbelt” sign. Please return to your seats and fasten your seatbelts.

The actress playing Cindy had to read these lines three different ways for this to occur. And because all three lines are given over the intercom system, the sound editor had to lay in three different tracks for the three scenes in question. This, to me, indicates a degree of intentionality.

But it still doesn’t determine what the intention is. It’s not necessarily the case that the Flashbacks are iterations in of themselves. When we get to comparing House of the Rising Sun, the 6th episode of the season, with …In Translation, the 17th, we’ll see just how much the direction of the show is oriented around the “third-person-close” mode of storytelling we discussed in the previous essay—the Flashbacks are subjective, containing only information known by the characters themselves. And indeed, looking at all the shots for Pilot Part 2, we again find that every shot is reflective of what the characters are experiencing; there are no “omniscient” shots. So we can explain any differences in these three Flashbacks, with the “seatbelts” line, as evidence of a very slightly unreliable narrator; each character remembered the line not quite the same.

Conversely, that the story is told in third-person-limited does not mean that something like multiple Flashbacks representing different iterations is not true. These conditions are not mutually exclusive.

It’s a Better Game Than… Checkers

It’s a Better Game Than… Checkers

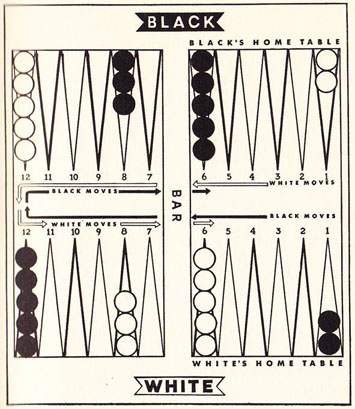

So, let’s take a look one of the more obvious metaphors for LOST: the backgammon game, as presented by Locke to Walt:

LOCKE: Backgammon is the oldest game in the world. Archeologists found sets when they excavated the ruins of ancient Mesopotamia. 5000 years old. That’s older than Jesus Christ.

WALT: Did they have dice and stuff?

LOCKE: Mmm hmm. But theirs weren’t made of plastic. Their dice were made of bones.

WALT: Cool.

LOCKE: Two players… two sides. One is light… one is dark. Walt, do you want to know a secret?

Given what we know of Jacob and the Man in Black, this is now a pretty obvious metaphor for the “game” they play over the fate of the Island. Which is to say, this scene has credibility. Especially with Locke holding up the game pieces so that they’re by his eyes, a conceit that recurs in Claire’s dream in Raised By Another. It’s a scene that pays off.

Backgammon is a more interesting game than Checkers, but there are similarities. In Checkers, you play on a checkerboard with your pieces moving diagonally. You capture other pieces by jumping over them. When your piece gets to the end of the board, it is “crowned” and can now go backwards. You win by capturing all of your opponent’s pieces.

Backgammon is more complex. Like Checkers, the player’s pieces move in the opposite direction relative to each other. And there’s an element of capture, which occurs when one of your pieces lands on an opponent’s piece that stands alone. (Live together, die alone, as they say.) But that’s kind of where the similarity ends. First, you move two pieces (blots) at a time, as opposed to one. The number of spaces the pieces can move is determined by rolling the bones; each die corresponds to one piece. You can only move to a point that isn’t occupied by at least a twinset of your opponent’s blots. You don’t win by getting your opponent off the board—on the contrary, you win by removing or “bearing off” your pieces via the respective exits.

Backgammon is more complex. Like Checkers, the player’s pieces move in the opposite direction relative to each other. And there’s an element of capture, which occurs when one of your pieces lands on an opponent’s piece that stands alone. (Live together, die alone, as they say.) But that’s kind of where the similarity ends. First, you move two pieces (blots) at a time, as opposed to one. The number of spaces the pieces can move is determined by rolling the bones; each die corresponds to one piece. You can only move to a point that isn’t occupied by at least a twinset of your opponent’s blots. You don’t win by getting your opponent off the board—on the contrary, you win by removing or “bearing off” your pieces via the respective exits.

Most interestingly, when a piece is captured, it ends on the center bar (hmm, an axis mundi?) where it must re-enter the game at the far end of the board. Think of it like this: capture (which in other games, like Checkers and Chess, is “death”) sends you to a kind of “purgatory” before you can get back into the game. Each time you’re captured, therefore, you in essence go back to the beginning. So not only does Backgammon have the mirror-twin aesthetic we’ve described so far, it also has an element of “looping.”

So the game is really a footrace. You can block other pieces, keeping them from advancing, or even make them go to spaces they wouldn’t other wise choose to go. And this can lend itself to some interesting tactics.

CLAIRE: There! Right there, that’s a kick! There! There, right there’s a foot! (Scene 20)

BOONE: We’ve all been through a trauma. The only difference is since the crash you’ve actually given yourself a pedicure. (Scene 15)

In Scene 15, we get this marvelous fight between Boone and Shannon. She’s sitting on the beach, and she’s finally having an emotional. Being properly empathetic about the dead man in front of her. Who saved her life by denying her and Boone first-class seats. And what does Boone do? He calls her “worthless,” just “sitting on her ass,” and then, when Shannon gets angry at him, he starts mirror-twinning her:

SHANNON: You know what? It is so easy to make fun of me, and you’re good at it. I get it.

BOONE: I wish I didn’t have to waste my time making fun of you. I wish I didn’t have a reason. Yeah, it is easy, Shannon.

SHANNON: Screw you, you do not have the slightest idea what I am thinking.

BOONE: I have a much better idea than you think I do.

The effect of Boone’s instigation propels Shannon to join the away team. Which is the only reason that anyone has any idea what the Frenchwoman’s Transmission said. Not that this does anyone any good, but Boone wouldn’t know that, would he? But he certainly knows how to needle his half-sister. If Boone actually had some foreknowledge, for instance, that the away team came back hearing a French distress call, and knowing that his sister spoke French, and knowing even better how to emotionally manipulate her… if he had the opportunity to go back and actually prod her to come with the away team?

Of course he would. And the nice thing about this kind of foreknowledge, couple with a theory of time-travel, is that it makes emotional sense. It’s still rooted in character drama.

So, with that possibility in mind, let’s take a closer look at Charlie’s Flashback. It involves the most blatant mirror-shot of the entire episode; Charlie’s character development is truly shown in front of the mirror.

So, with that possibility in mind, let’s take a closer look at Charlie’s Flashback. It involves the most blatant mirror-shot of the entire episode; Charlie’s character development is truly shown in front of the mirror.

I should point out that there’s something similar about both Flashbacks in this episode, Kate’s and Charlie’s. They are preceded by sound effects within the Flashbacks themselves. This is an early conceit of the show; by the time we get to House of the Rising Sun, those sound effects will be replaced the familiar whoosh for transition into and out of those Flashbacks that aren’t bounded by the hard break of a commercial interruption or the beginning of an episode.

Charlie’s Flashback begins with a tapping sound, the effect of tapping the arm of his chair with a ring. Which represents a loop. That sound effect begins before the Flashback, immediately after a bit of mirror-twinned dialogue:

CHARLIE: Every trek needs a coward.

KATE: You’re not a coward.

The emotional continuity here is one of faith. Kate expresses faith in Charlie. Then we hear the tapping ring, and then we’re back on the plane, and Charlie is jonesing for a fix. He rushes to the bathroom, and pulls from his checkerboard shoes a bag of heroin. He gets his fix, leans into the mirror…

…and then something really weird happens. He raises his hand to his forehead, as though some foreign thought has come to him. He drops his dope in the loo. But he doesn’t reach into the loo to retrieve the bag. No, he reaches for the handle, to flush it away. It’s as if that future emotional reality of Faith has traveled back in time and changed him for the better. But, obviously, he can’t flush the drugs away. Then he wouldn’t have come back to the cockpit with Jack and Kate, and Kate wouldn’t have expressed faith in him, and he wouldn’t have tried to flush the drugs.

At this point fate intervenes (ah, Fate, written on the loops of tape around the fingers of his left hand). Or, perhaps, the Universe has a way of… course correcting. The plane hits turbulence, Charlie is flung to the ceiling of the cabinet and then slammed to the ground… an instance of mirror-twinning. He rushes outside, and has a near-death experience, almost getting brained by the beverage cart. And then he scrambles down the aisle, finds an empty seat, and prepares for the plane crash.

That scene in the bathroom… it’s got a couple of continuity errors. The thing is, they both have something to do with loops. First, there’s the rubber band around the drugs, which Charlie removes and puts on his finger. Fingers? It switches back and forth between being looped around one finger and two. Almost like a count, or a twinning. Second, there’s a piece of tape looped around his necklace, which is itself a loop, and which has a loop at the end for a clasp. In the moment that Charlie drops the drugs, the necklace itself is reversed; the “loop tape” goes from being on Charlie’s right, to his left, and back to his right. The continuity errors therefore symbolize, yes, a mirror-twinning.

Well, it’s a theory. We know there’s time-travel in the show. And mirror-twinning is the show’s aesthetic. And there’s slyly hidden an Easter Egg about iterations on a loop, an Easter Egg the true extent of which is only apparent through the practice of close reading… translation… interpretation.

But who in their right mind would make mistakes on purpose?

SHANNON: It’s… it’s repeating.

SAYID: She’s right.

BOONE: What?

SAYID: It’s a loop. “Iteration”—it’s repeating the same message. It’s a counter. The next number will end…

October 14, 2015 @ 10:40 am

Excellent analysis. I’m going to really enjoy these. I’ve always loved part 2 for really focusing on all the secondary characters and giving each of them really interesting character beats.

October 15, 2015 @ 4:08 am

I have not seen Lost, nor do I have any intention of doing so; and yet I am finding this compelling. Thanks!

October 30, 2015 @ 7:57 am

Huge fan of LOST, loving your exegesis! Keep up the great work!