Lost Exegesis (Tabula Rasa)

One of the problems with Pilot episodes is that they’re made specifically in order to hook people (almost like fish) not just into watching a TV show, but to actually sign off on it being produced. As such, they tend not to be as representative of the series as a whole. So what a TV show has to do after its pilot is to kind of hit the reset button and start playing its cards, showing us what we might expect on a weekly basis going forward. As such, Tabula Rasa is a rather aptly named episode, given that it’s a fresh start for LOST, employing a number of techniques that we did not see previously.

One of the problems with Pilot episodes is that they’re made specifically in order to hook people (almost like fish) not just into watching a TV show, but to actually sign off on it being produced. As such, they tend not to be as representative of the series as a whole. So what a TV show has to do after its pilot is to kind of hit the reset button and start playing its cards, showing us what we might expect on a weekly basis going forward. As such, Tabula Rasa is a rather aptly named episode, given that it’s a fresh start for LOST, employing a number of techniques that we did not see previously.

For starters, we get a “Previously, on LOST” segment. It’s the sort of thing we’re all familiar with, nothing new under the sun in terms of TV, but just its very presence indicates what kind of show we’re dealing with, namely something that’s serialized. The vignettes in this segment briefly depict: the plane crash; the man wounded by shrapnel in his gut and Kate’s apparent interest in him; the fact no one has come yet to the Losties’ rescue; and a recapitulation of Locke’s explanation of backgammon to Walt (“Two players, two sides, one is light, one is dark”), that ends with Locke’s question to Walt, “Do you want to know a secret?”

The thing about a “previously” is that it’s supposed to remind us of what’s actually relevant in the previous episodes in terms of understanding what occurs in this one. Notably, then, we do not get anything about the Monster that tears down trees, or the Frenchwoman’s transmission, even though a significant portion of the character interactions in Tabula Rasa have to do with these big mythology questions. Furthermore, that bit with Walt and Locke is relatively long given that both characters are only part of a rather minor secondary plot thread in this episode. On the other hand, it certainly plays into the final shot of the episode, a shot full of foreboding, so it’s not like it’s pointless or anything.

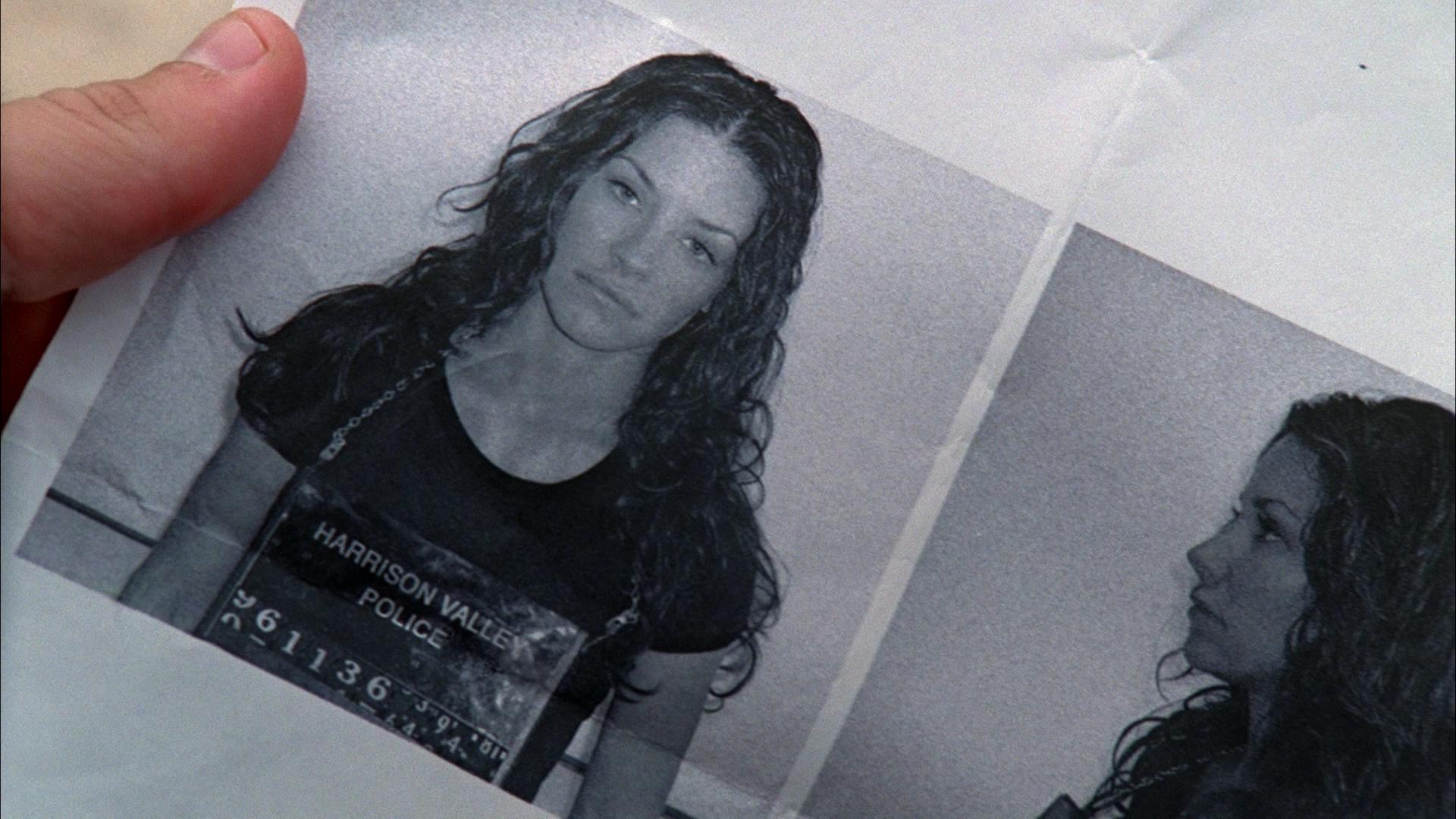

Another new element is the use of a “cold open” before the show’s title card. It’s actually here that the two major mysteries established in the pilot episodes are recapitulated, as well as establishing the focus of the episode, namely the discovery of Kate’s mug shot by Jack and Hurley.

So it should not be too surprising that the episode ends up being Kate-centric. And that’s a term I use very specifically, given the third major conceit introduced by Tabula Rasa – the episode features five Flashbacks, all of them about Kate. The Flashbacks themselves end up serving as the B-plot of the episode, detailing Kate’s time in Australia: a drifter, she ends up getting work at Ray Mullen’s farm, but he betrays her for a $23,000 rewards, setting up her capture by the Marshal. So not only do we see how she ended up on the plane, we also get a hefty amount of characterization – Kate would do almost anything to escape, like crashing Ray’s truck, but when the truck catches fire she pulls him to safety, at the cost of her own freedom.

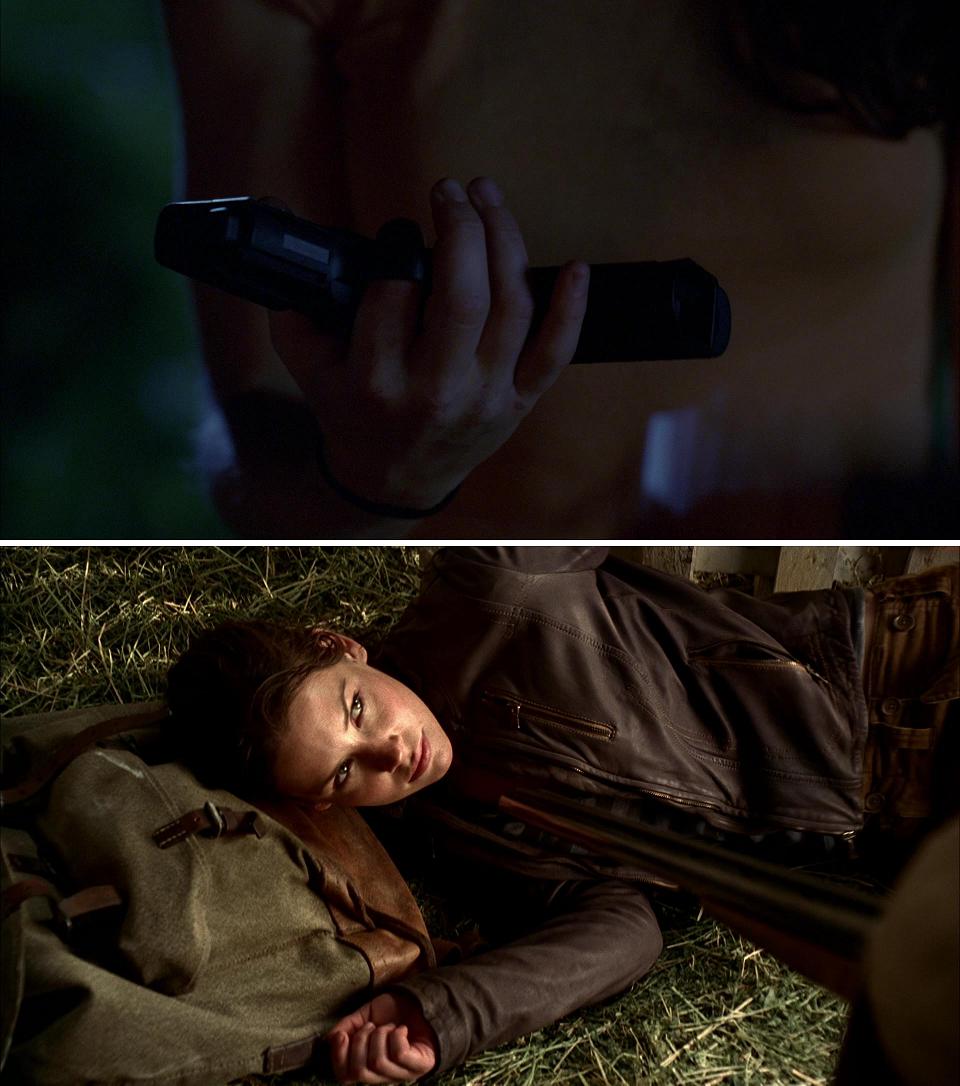

The Flashbacks are interesting, structurally speaking, beyond what they do to flesh out Kate’s character. Like the Flashbacks in Pilot Part 2, there’s a continuity between them and what’s happening to Kate on the Island. The first Flashback occurs when Kate is given the gun that Sawyer took from the Marshal – at that moment there’s a particular sound effect, the rising crescendo of a whoosh, plus the sound of a gun cocking, and then transition to the Flashback where Kate wakes up in a sheep pen to the click of Ray’s rifle being cocked and pointed at her.

The Flashbacks are interesting, structurally speaking, beyond what they do to flesh out Kate’s character. Like the Flashbacks in Pilot Part 2, there’s a continuity between them and what’s happening to Kate on the Island. The first Flashback occurs when Kate is given the gun that Sawyer took from the Marshal – at that moment there’s a particular sound effect, the rising crescendo of a whoosh, plus the sound of a gun cocking, and then transition to the Flashback where Kate wakes up in a sheep pen to the click of Ray’s rifle being cocked and pointed at her.

A similar transition occurs for the second Flashback: on the Island, Kate is looking at the unconscious Marshal in his tent, there’s a whoosh and the sound effect of a light switch being flipped, and then we’re in Kate’s Flashback as she prepares to leave Ray, to escape. This second transition is also marked by the use of slow-motion at the end of the Island shot. It’s even more interesting in that the return to Kate on the Island is also marked by a whoosh, just after Ray says that everyone deserves a “fresh start.” Unlike the return from first Flashback, which was just a hard cut from Kate and Ray in Australia to Hurley and Jack on the beach, no whoosh required.

So what we have here is a narrative convention that establishes a kind of connectivity between the Island story and the Flashbacks. That continuity is focalized on a character. Which is to say, it isn’t just a Flashback for the purpose of providing backstory, but strongly suggests that the Flashback belongs to the character. In these instances, it suggests that Kate is actively remembering her past.

So, for the third Flashback: she’s standing in the rain after Jack says he’s seen her mug shot and that he isn’t a murderer—in this moment, Kate realizes that he’s learned her secret. We get a music cue (Patsy Cline) that takes over the sound track, and then we move into Flashback, where Kate is riding in Ray’s truck and Patsy Cline is playing on the radio. In this scene, she discovers that Ray has learned her secret. When the Flashback is over, we cut back to Kate still standing in the rain, now in slow motion, while an extradiegetic sound effect resembling a soft echoing crash marks the transition. Given the similarity in content of these scenes, it’s not unreasonable to assume that the Flashback is a memory,

and specifically one that resembles what Kate has just gone through with Jack.

The last two Flashbacks are similarly constructed – using sound effects for transitions, and being related to the action that’s occurring on the Island. And this whole convention of limiting Flashbacks in an episode to a single character is really an elegant way for the show to structurally put a flag in the sand regarding one of its core concerns, that of Identity. It’s elegant, because it allows the show to spend an entire episode focusing on a single character, rather than spreading itself thin over the dozen or so that make up the entire ensemble. Furthermore, by positioning Kate’s “secret identity” as a mystery to be uncovered, which is only partly revealed (neither we nor Jack learn here what she did to get into this mess in the first place), the show effectively positions the character drama onto the same footing as its “mythology” of tree-crashing monsters, tropical polar bears, and French transmissions.

The One-Armed Man

The One-Armed Man

HURLEY: Yo, so where’s The Fugitive?

JACK: In the tent.

HURLEY: You let her in there alone?

An unusual detail in the story about Ray Mullen is that he’s missing his right arm – how he lost it, we never find out. But that’s not important. What’s important is that this detail, coupled with some select dialogue on the part of Hurley (who has an interesting extradiegetic role we’ll get to later) points us towards an intertextual reference that has some bearing on Tabula Rasa. Specifically, that reference is a TV show from the 60s called The Fugitive.

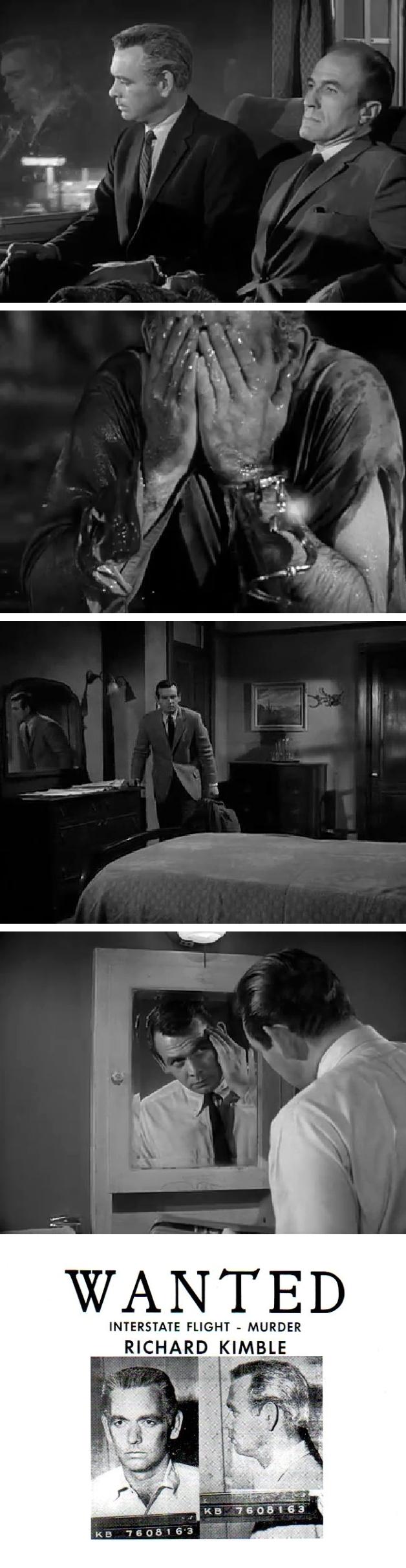

The Fugitive was kind of ahead of its time. It was a semi-episodic/semi-serialized story about Dr. Richard Kimble, a man wrongly convicted of the murder of his wife. He’s on the run from the law after miraculously escaping a train crash, pursued by the relentless police detective Lt. Philip Gerard.

Most episodes had Dr. Kimble taking on a new identity (like George Browning, for example) and a new job, then getting involved in a character drama – out of the goodness of his own heart – that would necessitate his moving on. It was a very well-regarded show, earning Emmy awards and guest appearances by top-notch actors, with a structure that allowed it to delve into a wide variety of dramatic conceits and trope. One week might be a meditation on domestic abuse or a cheating husband, while others might be medical dramas and action stories, what have you. Interspersed with the drama-of-the-week were the “mythology” stories that filled in the overarching story of Kimble’s escape, his efforts to track down the one-armed man, and the building respect of his nemesis, Detective Gerard.

Of course there are obvious similarities to Kate and Kimble – on the run, changing identities, always pursued, a one-armed man, getting betrayed on account of large rewards, and so forth. (In the movie adaption starring Harrison Ford, the Detective is even changed to a Marshal.) More interesting, though, is how The Fugitive can also serve as a mirror to LOST, which (by virtue of its many characters and the Flashback structure introduced in Tabula Rasa) can play in the sandbox of a wide variety of genres. Like a meditation on the ethics of euthanasia, for example, juxtaposed with an detective-chase yarn.

One episode of The Fugitive stands out in particular: the 14th episode of its first season, “The Girl from Little Egypt.” It’s only in that episode that we come to learn what actually happened to Kimble that got him into his predicament, beyond the brief synopsis that constitutes the opening credits of every episode. In “Little Egypt” Kimble is hit by a car, and in the hospital he ends up having Flashbacks that describe his marriage falling apart, the night his wife was murdered, and his subsequent trial, conviction, and miraculous escape. These Flashbacks are presented as memories, brought up in his delirious state, which the driver (the eponymous Girl) subsequently hears. The final Flashback is somewhat different – it represents Kimble telling the Girl a story – but even here it’s clear that the Flashback is more than just a case of telling a story out of order, but is integral to the story happening in the moment. It’s something that’s being experienced at some level by the characters themselves.

(Unlike, say, the use of Flashforwards in the final season of The Fugitive, a conceit used to begin episodes, before the credits.)

And of course, it’s not like The Fugitive or LOST are inventing anything new under the sun. This is just to point out the kinds of narrative techniques that they use, and how they’re consistent with character-oriented drama. This gives us a demonstration of LOST being “literary” in the sense of it adapting techniques used in the past, and indeed demonstrating a measure of self-consciousness about that. Given that, we must consider the “discourse” or “telling” of the narrative, just as much as the “events” or “story”; the discourse informs us of how to read the show. Here we’ve identified not just a relevant intertextual reference, but also the means by which LOST divulges its own secrets – we found that reference to The Fugitive from a bit of dialogue and an unusual, distinctive character detail, and the exploration of that hunting ended up bearing out on several parallels, aiding in our understanding of the show itself.

An Essay Concerning Human Understanding?

The Fugitive was a sort of “buried treasure” that might only be unearthed through close reading, even a “paranoid” reading if you wish. A less covert bit of intertextuality is presented through the episode’s title, Tabula Rasa. It’s Latin, and it’s taken to mean “blank slate,” which is obviously one of the themes of the episode. Ray Mullen (not just a farmer, but a shepherd given that he keeps sheep) tells Kate that he understands the desire for a “fresh start.” This is mirrored by Jack at the end of the story, when he says he’d prefer not to know what Kate did, a rather remarkable about-turn given his earlier keen interest, perhaps motivated by his own irony – for shortly after declaring, with righteous fury, that he’s not a murderer, he ends up having to murder the Marshal to put him out of his misery after Sawyer’s attempt fails horribly.

But there’s another, more common meaning to the term tabula rasa than what’s on offer here. It’s worth taking a closer look at, given we discover that one of our characters is named “Locke.” After all, his speech to Walt figured prominently in the “previously” segment, and that he’s featured in ominous closeup at the very end. We don’t know Locke’s first name yet, but it’s certainly no secret that a very important historical figure named John Locke advanced a “tabula rasa” theory back in the 17th Century.

But there’s another, more common meaning to the term tabula rasa than what’s on offer here. It’s worth taking a closer look at, given we discover that one of our characters is named “Locke.” After all, his speech to Walt figured prominently in the “previously” segment, and that he’s featured in ominous closeup at the very end. We don’t know Locke’s first name yet, but it’s certainly no secret that a very important historical figure named John Locke advanced a “tabula rasa” theory back in the 17th Century.

Until we get confirmation that “Locke” is indeed “John Locke” (which would suffice as another instance of the show using intertextuality as foreshadowing, much like Walt’s comic book foreshadowing the presence of a polar bear on the Island) let us instead just review the historical Locke’s tabula rasa theory. It’s outlined in his Essay Concerning Human Understanding, which was one of the foundational works of philosophy in the Western Renaissance.

If we can find out how far the understanding can extend its view; how far it has faculties to attain certainty; and in what cases it can only judge and guess, we may learn to content ourselves with what is attainable by us in this state.

The Essay itself, as evidenced from this quote, has a rather grand ambition, that of how human beings actually come to understand anything at all, and hence what scope our epistemology may entail. It covers a tremendous amount of ground – first, though, it works to tear apart the philosophy of “nativism,” specifically that we are endowed with certain knowledge at birth. Only then does Locke instead propose something different:

Let us then suppose the mind to be, as we say, white paper, void of all characters, without any ideas:—How comes it to be furnished? Whence comes it by that vast store which the busy and boundless fancy of man has painted on it with an almost endless variety? Whence has it all the MATERIALS of reason and knowledge? To this I answer, in one word, from EXPERIENCE.

Mind you, I’m not interested at this point in debating whether Locke is right or not, just to elucidate his position and hence what kinds of relevant themes are being evoked for LOST. So, at this point, we should note that Locke never actually uses the term “tabula rasa” in the Essay—but that is nonetheless the term by which his theory of learning is known. We are “white paper” upon which Life, the Universe, and Everything inscribes. Well, except for one caveat:

By reflection then, in the following part of this discourse, I would be understood to mean, that notice which the mind takes of its own operations, and the manner of them, by reason whereof there come to be ideas of these operations in the understanding.

For Locke, “reflection” is the other means to knowledge – we think about our experiences, combine ideas together into more complex thoughts, and so come to deeper understandings of ourselves and the universe around us. But this “reflection” is used in a very particular sense, as Locke distinguishes:

To think often, and never to retain it so much as one moment, is a very useless sort of thinking; and the soul, in such a state of thinking, does very little, if at all, excel that of a looking-glass, which constantly receives variety of images, or ideas, but retains none; they disappear and vanish, and there remain no footsteps of them; the looking-glass is never the better for such ideas, nor the soul for, such thoughts.

Reflection is not just the action of a mirror. For Locke, reflection hinges on both memory, as evidenced above, and especially on Reason. And in terms of LOST, going back to the structure of the Flashbacks, there is a sense of “reflection” to them, that one’s experiences are informing one’s emotions and actions in the present Island story. And indeed, the characters themselves are “white paper” regarding what they know of each other. Who they “are” on the Island is based in large part on their current interactions, not their past lives. So it’s very noble for Jack to say he doesn’t want his “white paper” to be inscribed with what Kate did, because the Kate he knows now, through his own experience, is ultimately the one that matters.

So there is an aptness to the invocation of the historical Locke here. Which, if it turns out that LOST’s Locke is actually named John, would also be demonstration that the reference isn’t gratuitous, but demonstrates a knowledge of the philosophy being invoked. In such a case, then, we can make the argument that understanding LOST through its intertextuality and referential implications is a valid tack to make.

Moments of Grace

I want to close this portion of the Exegesis, before the Intermission, on the nature of the episode’s denouement. For again, we get something here that we didn’t get in the pilot episodes. The pilot episodes were all about setting up the hook of the show, and as such they presented us with dramatic mysteries concerning the nature of the Island. But Tabula Rasa turns the tables on this conceit, mostly. Yes, it ends with a dramatic mystery, by virtue of that very long, very close-up, very circular tracking shot on Locke, with a dark turn in the musical score as it fades to black before the smash cut to the LOST title card. But this is hardly an Island mystery – rather, it’s a character mystery. Who is this guy?

Before that, though, we get a montage of our various Losties that is decidedly upbeat, and which actually speaks to the use of “tabula rasa” evidenced throughout the story, not that of John Locke’s theory on human understanding, but one that’s rooted in a decidedly religious concept, that of Grace.

Before that, though, we get a montage of our various Losties that is decidedly upbeat, and which actually speaks to the use of “tabula rasa” evidenced throughout the story, not that of John Locke’s theory on human understanding, but one that’s rooted in a decidedly religious concept, that of Grace.

Let us first describe what we mean by “Grace.” It might be best understood in relationship to “Mercy.” Mercy happens when we deserve some kind of punishment, only for it to be withdrawn. Like, drinking too much one night, but not getting a hangover in the morning. That’s a mercy. Grace, on the other hand, is when we ended up receiving some kind of boon, despite not deserving it, and especially in those moments when we’ve “given up” and have “let go” of any sort of expectation.

It’s this latter sense that informs the “fresh starts” of the montage. Hurley finds his CD player, and it works, and now he gets to listen to Joe Purdy’s “Wash Away,” even though Hurley’s been too busy hanging around Jack and being suspicious of Kate, as opposed to sorting through the luggage like Claire has. Boone gives Shannon a pair of repaired sunglasses, even though Shannon was heartless about wanting the Marshal to just go ahead and die already. Sayid tosses an apple to Sawyer, who’s moping about his failed euthanasia of the Marshal, and who hasn’t done anything to support Sayid’s efforts to keep the camp organized – and the look on Sawyer’s face speaks volumes about what this gesture means. (Charlie gives himself a new letter on his finger tape, changing the word “FATE” to “LATE” – well, he covers up the F, but still, there’s a measure of grace here, too, that they’re simply running late regarding to their lives back home, rather than being fated to this crash landing on the Island, but it’s not quite what I’m going for here. Or is it?)

The big moment is saved for last, though. Locke has given Vincent to Michael, even though Michael doesn’t deserve this, given he didn’t really do much of anything to find Walt’s dog. But what this really does is then give Michael a “fresh start” with his son (who also doesn’t deserve getting Vincent back, given his being sullen and uncooperative with his father). So one dog confers two moments of grace.

And yes, though we close on a “mystery” – who is Locke anyways, and what’s his deal? – it’s worth noting that the Pilot episodes didn’t have anything resembling a moment of grace. This is the first episode, then, to provide a measure of closure at its end. And not, we should note, the sort of closure that comes with answering mysteries, but emotional closure. The episode has finally established that this is a group, their own circle, and that the fresh start they get on this Island is one that will come together.

INTERMISSION

INTERMISSION

HURLEY: We’ll let Johnny Fever take care of her when he gets better.

This intermission is brought to you by WKRP in Cincinnati, home of the city’s #1 DJ, Doctor Johnny Fever. Woo! Unlike The Fugitive, there’s no real discernible reason for there to be a reference to WKRP. Not that there aren’t similarities. Like The Fugitive, WKRP was a largely episodic TV show, but it did have an ongoing mythology regarding its characters, and some (Bailey Quarters, in particular) actually developed over the course of the show’s four season. But there the similarities end. I mean, Tabula Rasa isn’t exactly played as a comedy. And it doesn’t feature a disc jockey.

Well, let me take that back. Before I do, though, let’s reflect a bit on the production aspects of WKRP. This was a television show that played snippets of actual popular music as part of its regular storytelling. Which can be tricky. Because music is copyrighted, and purchasing rights to music for television can be fraught with difficulty. In the case of WKRP, the rights eventually ran out in the midst of it being one of the most popular syndicated television shows (in other words, being rerun five days a week), long after they stopped making new episodes. And mind you, this didn’t just affect syndication, but long delayed the release of the show on DVD.

So what did they do? How do you air episodes that can’t be aired due to expired music copyrights? Simple. You cover up the music. Get a cover band to produce something that sounds very similar to what was there before. And if the music’s playing in the background during a scene where the characters are speaking, you get voice doubles to redub the lines… again with innocuous music. Which is actually ironic, given that Doctor Johnny Fever was passionate about music, always wanted to play the best music, music with taste and history and relevance. Original music. Real music. Not fakery. Alas.

But there’s a metaphor here, this idea of going back and covering up something. It’s certainly applicable to Kate’s desire to cover up her past, to live as if she weren’t a fugitive. So maybe WKRP is apt after all.

Enough of TV shows. Time for some music! I’ve set up the pictures here to open up the relevant songs on YouTube (in a new window or tab). So let’s just sit right down, relax, open our ears real wide and listen to the songs in Tabula Rasa. And I’m not talking about the score by Michael Giacchino, but the popular music that informs a couple of the episode’s themes.

Enough of TV shows. Time for some music! I’ve set up the pictures here to open up the relevant songs on YouTube (in a new window or tab). So let’s just sit right down, relax, open our ears real wide and listen to the songs in Tabula Rasa. And I’m not talking about the score by Michael Giacchino, but the popular music that informs a couple of the episode’s themes.

First up we’ve got Patsy Cline singing “Leavin’ on Your Mind,” which plays on the radio while Ray is driving Kate to the apocryphal train station. Apt and ironic at the same time, the song is a simple plea for the singer’s lover to just get on with it and leave, if there’s a new love in the picture. Better to suffer now, get it over – one may learn to love again. Kate, of course, is someone who’s always leaving. She tried to leave Ray Mullen in the middle of the night. In the Pilot episode, she tells Jack that she wants to “run.” Kate, in other words, isn’t the singer of the song, but the subject of the song.

Sadly, “Leavin’ on Your Mind” was Patsy Cline’s last single before she died in a plane crash.

The other song featured in Tabula Rasa is Joe Purdy’s “Wash Away,” which plays over the final montage of the episode. Again, it’s a simple song. Joe sings to the Lord that he’s got “troubles” that are going to wash away, and “sins” that are going to wash away, which is very much in keeping with the denouement’s theme of getting a fresh start, a clean slate, the chance to begin again.

But then the song takes a dark turn – in the third stanza, as this time it is “friends” that have already washed away. Here, then, the blank slate is that of death. This leads neatly into the bridge, which is four lines of “crying alone,” but which turns from “been crying alone” into “no more crying alone” halfway through.

But then the song takes a dark turn – in the third stanza, as this time it is “friends” that have already washed away. Here, then, the blank slate is that of death. This leads neatly into the bridge, which is four lines of “crying alone,” but which turns from “been crying alone” into “no more crying alone” halfway through.

The song returns to its upbeat refrain – now it’s the “lonely” which will wash away, but notice that it’s now “we” who will wash away. Interesting. What does it mean to wash away? It almost sounds like dying. In which case, the loneliness will be replaced with the reunion of those who’ve gone before. In the Near-Death Experience community, this reunion is called a Homecoming. Yeah, we’ll get there eventually. Anyways, the song comes full circle with a repeat of “troubles” washing away, and ending with a coda that it’s “this old river” that’s gonna take them away. Given the fairly common metaphor that “time is a river,” we have a nice little beat here at the end.

And sure, while the song works extremely well for the episode’s denouement, and may even yield some metaphorical implications that would be well worth bearing in mind as the Exegesis progresses, what’s so striking about it here today isn’t just the song itself, but how it’s transformed from something that Hurley is listening to on his tinny CD player to something that takes over the entire soundtrack. Which gives Hurley a kind narrative agency that we haven’t seen from the other characters; he is ostensibly informing the tone of this montage. Interestingly, this is somewhat mirrored in the structure of the episode, which also begins with a montage. But that montage doesn’t feature music, and rather than being focused on our Losties, it’s on all the extras who mill about on the beach. Only one of our focal characters, Claire, is featured in that opening montage. And as we’ve pointed out before, Claire and Hurley have been juxtaposed before, in both Pilot episodes, simply by virtue of having big bellies.

So while Tabula Rasa doesn’t have the intense aesthetic of mirror-twinning that we’ve detailed in the first two episodes, there’s still a nod to it here. And with that, it’s time to look at this episode “through the looking glass,” with foreknowledge of what’s to come, both in terms of LOST and of the Exegesis itself.

LOST Through the Looking Glass (Tabula Rasa)

In Kate’s third Flashback, which sits at the center of the episode, there’s a concern with mirrors, at many levels of the narrative. Most obviously, at the level of the plot. Kate and Ray are driving in a pickup truck, Patsy Cline playing on the radio. Kate catches Ray constantly looking in his rearview mirror, and it’s then that she realizes that something is up. Ray is anticipating a vehicle behind him. His gaze into the mirror is the “tell” for Kate that catches her up on the plot.

In Kate’s third Flashback, which sits at the center of the episode, there’s a concern with mirrors, at many levels of the narrative. Most obviously, at the level of the plot. Kate and Ray are driving in a pickup truck, Patsy Cline playing on the radio. Kate catches Ray constantly looking in his rearview mirror, and it’s then that she realizes that something is up. Ray is anticipating a vehicle behind him. His gaze into the mirror is the “tell” for Kate that catches her up on the plot.

The mirror is also a part of the thematic discourse. Kate takes a look in her own rearview mirror, and this is a shot that’s presented for our own viewing pleasure – an interior POV shot of the mirror itself, which shows Kate’s past literally catching up with her. Naturally, the shot is repeated – twinned – within the scene.

But let’s get down to the nitty gritty here, which is how “mirrors” function at the production level. The flashback scenes with Kate and Ray are happening in Australia. However, the show itself is shot in Hawaii. Which presents a bit of a problem when it comes to scenes that have driving in them… because in Australia, they drive on the other side of the road. (Well, the other side for Americans, who drive on the right. Obviously Aussies and Brits both drive on the left.) And not only do they drive on the other side, but the vehicles themselves are manufactured as mirror images: the steering wheel is on the right instead of the left, so the driver’s POV is nearer the center of the road as opposed to the edge.

Australia’s the Key to the Whole Game

Australia’s the Key to the Whole Game

The easiest solution for a production that’s attempting some level of verisimilitude on a television budget is not to ship Australian cars to Hawaii and drive on the wrong side of the road, violating state laws, but to simply reverse the shot at the level of editing. Which is exactly what we have here. We can tell through careful observation of the actors playing Kate and Ray. Evangeline Lilly, for example, has an almost perfectly symmetrical face, except for her upper front teeth – the right one is ever so slightly longer than the left. But in the Australia driving shots, this imbalance is reversed. Likewise, Nick Tate’s left eye is more pinched than his right; in the truck scenes, this too is reversed. Because they flipped the shots.

We aren’t meant to notice this, of course. The production team has actually been very careful about planning these shots. For while Ray Mullen has a prosthetic right arm, Nick Tate does not. But as we can see when he’s driving, he’s driving with what appears to be his left arm – look at the wedding ring on  his finger. In truth, though, he’s driving with his right, and the prosthetic is reversed. Same for the bangle that Kate wears on her right wrist – in the truck scenes, the actress is wearing the bangle on her left, so when they reverse the shot, the continuity of her costuming will be preserved.

his finger. In truth, though, he’s driving with his right, and the prosthetic is reversed. Same for the bangle that Kate wears on her right wrist – in the truck scenes, the actress is wearing the bangle on her left, so when they reverse the shot, the continuity of her costuming will be preserved.

This attention to detail even applies to the vehicles. In a couple shots we see the license plates of the Marshal’s SUV and Ray’s truck. The plates aren’t reversed in the shots, which means that the prop department had to make reversed license plates just for this scene. So Australia, “down under,” is a kind of mirror-world in some respect, at least at the production level.

Now, you may be asking, “Why the fuck are you paying attention to mirrors, Jane?” Fair enough. It’s surely not the same as paying attention to the emotional nuance of the actors, for example (which there’s plenty, plenty of; the acting in LOST is truly phenomenal). But as we pointed out in the Pilot episodes, Mirrors are part of LOST’s aesthetic. A part of its discourse. And as demonstrated above, the discourse of the narrative is relevant to understanding the show, especially given that certain aspects of the show (specifically, the nature of the Island) were never revealed at the level of the plot. So this is what we’ve got to work with.

Here’s an interesting thing about the “reversed shots” in this episode – the rigamarole in Australia isn’t the only place to find them. On the Island, there’s a scene early in the episode where the away team talks around the campfire at night – which is where we get Charlie’s bit about how satellites in space can take pictures of license plates, and Sayid’s retort that if only they were all wearing license plates, but that such photography only works when you know where to point and shoot. Just in of itself, this dialogue demonstrates a meta-awareness at the script level, given that in this episode there’s a concern at the production level of pointing and shooting at license plates (not to mention that prop of Kate’s mug shot, which also has a kind of “license plate” hung around her neck).

However, it’s what Sawyer has to say that’s of particular interest:

SAWYER: Okay, really enjoyed the puppet show. Fantastic. But we’re stuck in the middle of damn nowhere. How about we talk about that other thing? You know that transmission Abdul picked up on his little radio? The French chick that said, “They’re all dead.” The transmission’s been on a loop for… how long was it, Freckles?

It’s in these lines (the ones underlined) that the two reversed images of Sawyer appear; we can tell by the lighting, and “cut” above Sawyer’s eye. Unlike the shots that are attempting to recreate the experience of driving in Australia, there’s no real good reason (aside from, maybe, line of sight, but even then he’s in a circle of people looking at all angles towards the other people) for these two shots of Sawyer to be reversed. And yet they are!

Perhaps… perhaps it’s the lines themselves that are important. “Damn Nowhere,” a description of the Island’s location. And “they’re all dead,” which is echoed in Jack’s line at the end when he says, “Three days ago we all died.” There’s certainly a reason why early theories of the Island postulated that it was Purgatory, and that the show was actually about the death-throes of the Losties.

But there’s a few other cues in Sawyer’s speech to note. First, the appearance of the word “other,” which is of course how the Losties eventually refer to the, well, other inhabitants of the Island. Here, though, Sawyer is talking about “that other thing,” namely that the Frenchwoman has said everyone was “dead.” And yes, let’s joke about “the other side” as a euphemism for passing on. But the end of Sawyer’s speech zeroes in on the fact that the Frenchwoman’s transmission was on a loop. And as we’ll see later in the Exegesis, there’s some very good reason to believe that on the Island, death releases one’s consciousness to “go back” and (as if in a loop) revisit moments in the past.

The other “reversed image” on the Island occurs after the Marshal tries to strangle Kate, right after her second Flashback. Jack intervenes, pushes the Marshal down, and then explains that the man has gone into sepsis, which means he’s going to die. The moment Kate realizes the Marshal is actually going to die, she’s presented in a reversed image in the tent. Again, there’s absolutely no reason for this shot to be reversed. Thematically, though, it’s apt.

But there’s nothing loopy about that scene. Where are the loops, Jane? Loops and reversed images, that’s what you’re talking about, right? Well, as it turns out, there’s a couple of shots in the Flashback that are reversed. Well, more specifically, that are not reversed… when they should be.

But there’s nothing loopy about that scene. Where are the loops, Jane? Loops and reversed images, that’s what you’re talking about, right? Well, as it turns out, there’s a couple of shots in the Flashback that are reversed. Well, more specifically, that are not reversed… when they should be.

They occur in the scene where Kate grapples with the steering wheel of the truck, after the discovery of Ray’s betrayal. The truck veers off the road, then flips over. And we see the truck twirling in mid-air from three different angles. The second of those angles is “reversed.” We can tell by looking at the reddish colored fence-post, and the direction in which the back window flies off. Again, I’m not so sure this makes cinematic sense, given how that middle shot shows the truck spinning in the opposite direction. Symbolically, though, it’s rich. Here we have a juxtaposition of the “circle” and the “mirror,” so to speak.

A similar juxtaposition occurs shortly thereafter, when Kate is pulling Ray out of the truck. The shot should be reversed (as we’re still dealing with a vehicle that’s supposed to be reversed in all its shots) but it isn’t.  And in this particular shot, the jerky camera momentarily comes into focus just so we can see that Ray’s wedding ring is now on the wrong hand. Again, a juxtaposition of mirror and circle.

And in this particular shot, the jerky camera momentarily comes into focus just so we can see that Ray’s wedding ring is now on the wrong hand. Again, a juxtaposition of mirror and circle.

The thing is, this is an extremely important character beat for Kate. After risking Ray’s life to engineer her escape, she then pulls the man to safety. That’s the beat bookended by these weird shots. And all within the Flashback where, on the Island, she’s preparing to speak to the Marshal for the very last time, on his deathbed. Let us suppose, for the purposes of this Exegesis, that Kate is reflecting on the nature of her capture. Despite what the Marshal says, just because she pulled Ray Mullen to safety doesn’t mean she wouldn’t have been caught. If Kate had regret about, say, killing Ray, she might wish she’d pulled him to safety in the end. She doesn’t want another murder on her hands. And this is why she earns a moment of grace in the end. Because whether she would go back to change things so that Ray doesn’t die, or whether she’d always go back to make sure Ray doesn’t die, she’s still sacrificed what’s precious to her – her freedom – in service of another human being. Which is what’s ultimately heroic about Kate, when all is said and done.

Me, I’m in favor of the idea that she’s actively rewritten her past, but in a way that’s still free of paradox, for she still ends up getting captured and coming to the Island, which is where time-travel is conferred in the first place. I’m especially in favor of this idea, given the WKRP reference and what they had to do on the production side to cover up songs after the copyrights ran out. Of “troubles” being washed away. And especially given the title of Tabula Rasa. It’s Latin. A “dead language,” as Juliet pointed out once. It refers to a wax tablet, which could be melted for reuse. In other words, the old words would be erased (yes, this word derives its etymology from rasa), so that new ones could be inscribed.

Apocrypha Now

We conclude with what will be a periodic entry in the Looking Glass portion of the Exegesis, “Apocrypha Now.” For ages now there’s been a bit of debate in the LOST community regarding what parts of the text are actually “canonical.” It’s not an unreasonable question to ask, given the sheer amount of LOST-related material that’s been made available throughout the show’s run.

For example, between Seasons 2 and 3 there was a LOST Alternative Reality Game that ran on the web that summer, which unveiled a lot of the Dharma Initiative backstory, including a wealth of things that never made it into the televised show. There were spin-off books. A video game. Another web game. Thirteen “missing pieces,” short filmed scenes released on people’s mobile phones. The opportunity to actually “join” a reconstituted Dharma Initiative. A special Marvin Candle feature that played at the San Diego Comic Convention; a LOST University, with classes on stuff like how to read Egyptian hieroglyphs, and the dynamics of Us & Them psychology; hell, there was a jigsaw puzzle with a coded message on the back, in invisible ink , that required a copy of Henry James’s A Turn of the Screw to decipher.

It is officially the position of the Exegesis that only an examination of the broadcast episodes (including the 13 “mobisodes”) – the official “canon” – are necessary and indeed sufficient for determining the nature of the Island and indeed LOST itself. That said, we’ll certainly be looking at some of the “non-canonical” materials as well, if only to demonstrate that they share many of the thematic and extradiegetic features of the show proper. We shall be referring to these materials as the show’s “apocrypha.”

“Apocrypha” is an interesting word. It is, of course, now wrapped up in the determinations of the Christian denominations regarding what texts are part of their ecclesiastical canons and which texts have been rejected as spurious or false, usually on the grounds of inconsistency, doubtful authorship, or dubious authenticity. But the word itself derives from the Latin apocryphus, “secret, not approved for public reading,” and that from the Greek apokryphos, “hidden, obscure” (apo- “away” + kryptein “to hide”). So there’s a hidden meaning in the word apocryphal that’s delightfully self-referential in this day in age. I’m encouraged to take the attitude of “treasure hunter” when it comes to LOST’s apocryphal materials.

Tabula Rasa offers a couple of canonical reasons for taking such an approach. First, let us consider the deleted scene from this episode now called “Finding the Tell.” It features Locke and Walt talking about how to “bluff” in poker – that is, how to lie, which Locke teaches to Walt via reverse engineering. He points out how to discern the “tells” of people who are lying.

LOCKE: The easiest tell someone makes is with their body. You tense up, make a fist, curl your toes… another amateur mistake, some players get very defensive when they’re lying. More experienced players use distractions to keep your attention off their cards. Others avoid contact altogether. They isolate themselves for fear of being unable to hide the truth. And some people… you just can’t read at all.

Interspersed with this dialogue are shots of various Losties. Charlie and Claire are presented for tensing up. Shannon and Boone for being defensive. Sayid is featured for using distractions. Sawyer for isolating himself. And Kate is the one who can’t be read at all. This deleted scene is particularly interesting not for the conversation per se – I don’t care at all that Locke is teaching Walt how to read people – but for how the text itself is teaching us how to read it. Watch the characters. Learn their tells. Because they are so very often lying. (And so is the text. What are its tells?)

We certainly get lying liars who lie in Tabula Rasa. Sayid, for example, certainly uses “distraction” to avoid telling the people on the Beach about the Frenchwoman’s transmission – he instead takes a leadership position and starts organizing people to facilitate their long-term survival. And of course there’s Kate, who’s not divulging anything of her past to Jack –as we saw in the “previously” referring to the pilot episode, she’ll step sideways of a question she’d prefer not to ask:

KATE: Do you think he’s going to live?

JACK: Do you know him?

KATE: He was sitting next to me.

Kate told the truth in her answer to Jack – the Marshal was sitting next to her, after all. This is a very effective way to lie, of course. Interestingly, though, Jack is not one of the Losties pointed out by Locke in his “telling” speech. However, we’re given the opportunity to discern Jack’s “tells” when he lies to  Kate after she asks him if the Marshal has said anything. Jack’s tell is to look away. But what’s so interesting about this tell is that it’s also part of the grace-note at the end of the story. Jack tells Kate that he doesn’t want to know her past… which, as we’ll eventually discover, is a bit of a lie; Jack is very interested in knowing and understanding Kate. But at the same time, Jack recognizes that if he’s going to get anywhere with Kate, he’s got to back off… and by giving her a “fresh start,” he too gets a measure of forgiveness for killing the Marshal, even if that forgiveness is only given to him by himself.

Kate after she asks him if the Marshal has said anything. Jack’s tell is to look away. But what’s so interesting about this tell is that it’s also part of the grace-note at the end of the story. Jack tells Kate that he doesn’t want to know her past… which, as we’ll eventually discover, is a bit of a lie; Jack is very interested in knowing and understanding Kate. But at the same time, Jack recognizes that if he’s going to get anywhere with Kate, he’s got to back off… and by giving her a “fresh start,” he too gets a measure of forgiveness for killing the Marshal, even if that forgiveness is only given to him by himself.

This idea of getting to “start over,” of having the slate wiped clean, then, is also somewhat of a lie. We can try to forget the past, erase that history, but it’s still there. It still informs us of who we are. But that doesn’t mean that it’s wrong to hide away the past. To keep it secret. Because secret isn’t just for the monstrous, but for what is fragile. For what isn’t “approved for public reading.” In other words, the “fresh start” is in fact a form of apocrypha.

And I think it’s very deliberately a part of the text’s concern with Identity, and how we all everybody are Mystery Boxes to each other. Consider, for example, the name that Kate chooses for her interactions with Ray – she calls herself “Annie.” The name is derived from Hannah, and that from the Hebrew Channah, which means “favor” or “grace.” But “Anna” became popular only in the Middle Ages, among Western Christians, because of Saint Anna, who was recognized at the mother of the Virgin Mary. Which is terribly interesting, because the Bible never names Mary’s mother. No, that naming convention comes from Infancy Gospel of James… which is an apocryphal work. And we really should pay attention to this one, given that all of Kate’s fake names are taken from Saints.

“Kate,” by the way, derives from the Greek Aikaterine. It’s a name with many meanings, apparently, given the debate around its etymology. Possibly from the goddess Hecate (hekas, “far off”) who was a goddess of magic and dogs and ghosts, as well being knowledgeable of herbs and the Underworld – in some traditions, she is the Savior. Certainly something to keep in mind, given Kate’s nature and the return of Vincent in this episode.

Later variations of Katherine (with the H added from Katerina) are associated with the Greek katharos, which means “pure” and is also the root of the dramatic principle of catharsis (and, of course, “purge”). But going back to early Greek, we also have hekateros, which means “each of the two.” And this is  interesting given Kate’s proclamation to Sawyer in Pilot Part 2 that “No girl’s exactly like me,” coupled with the Marshal’s observation in Tabula Rasa, “You really are one of a kind.” It’s weird, though, Kate’s reaction to this. She looks down and away. Almost like Jack’s tell when he’s lying. She looks away.

interesting given Kate’s proclamation to Sawyer in Pilot Part 2 that “No girl’s exactly like me,” coupled with the Marshal’s observation in Tabula Rasa, “You really are one of a kind.” It’s weird, though, Kate’s reaction to this. She looks down and away. Almost like Jack’s tell when he’s lying. She looks away.

Which rather begs the question… Are there two Kates?

November 3, 2015 @ 9:45 pm

Every time I read one of these posts I want to rewatch the whole series over again! The point about the reversed shots blew my mind!

November 4, 2015 @ 3:10 pm

Don’t forget, Kate’s also a Gemini. 🙂

LOVING these posts, please keep them coming. I’ve always found this show so rich, and you’re showing me even more. I especially love how you point out Hurley’s special narrative authority, and how he’s associated with the togetherness of the group. Very interesting, given his role in The End.

November 19, 2015 @ 1:05 am

Great stuff, thanks Jane.