Lost Exegesis (Walkabout)

So I guess we were right, back in the Tabula Rasa entry, about Locke’s first name being John, an invocation of the historical John Locke. We must be, like, psychic or something.

So I guess we were right, back in the Tabula Rasa entry, about Locke’s first name being John, an invocation of the historical John Locke. We must be, like, psychic or something.

A brief history, then. John Locke was a very privileged white man, born in 1632, England. He went to Oxford, studied with such famous scientists as Newton and Boyle, and determined to become a doctor. By 1666, Locke had teamed up with Dr. David Thomas to run a laboratory, probably a pharmacy. Through Thomas, Locke met Lord Anthony Cooper (one of the richest men in England and later the Earl of Shaftesbury) and became his personal physician. Lord Ashley also helped secure a government job for Locke, and for the next ten years or so Locke lived at Lord Ashley’s estate. Locke eventually went back to Oxford and received a Bachelor of Medicine and a license to practice.

But Locke isn’t primarily known as a physician so much as a philosopher, indeed a founder of liberalism. Mind you, we’re talking about the 17th Century. Locke isn’t a “leftist” in the modern sense of the term. Rather, his philosophy forms part of the bedrock of capitalism, from his early theories on prices, money, unlimited accumulation, and a theory of government oriented around the protection of private property versus one that is motivated by, say, compassion. Much of this philosophy is rooted in his conception of our “state of nature”:

“To understand political power right, and derive it from the original, we must consider, what state all men are naturally in, and that is, a state of perfect freedom to order their actions, and dispose of their possessions and persons, as they think fit, within the bounds of the law of nature, without asking leave, or depending upon the will of any other man.”

— John Locke, Second Treatise

So it’s amazingly prescient, given the state of pigfuckery today that LOST’s Locke ends up bringing home a boar. But on the Island, John Locke is not presented as a literal embodiment of the historical figure, despite his constant admonishment, “Don’t tell me what I can’t do!” On the contrast, he’s a frustrated man who has experienced a kind of rebirth, a literal “ascension” given the miraculous restoration of his legs.

Hence the Opening Eye motif at the beginning of the episode.

As mentioned in the exegesis of Pilot Part 1, the Opening Eye is fraught with symbolism. An awakening, becoming aware of an inner truth, a spiritual revelation. Even a resurrection. But Locke’s eye isn’t meant to be “read” in the same way as Jack’s. Locke’s right eye (or, rather, “eye”) is bifurcated by a scar running vertically down “across” is center. His insight, then is “crossed” with Jack’s.

As mentioned in the exegesis of Pilot Part 1, the Opening Eye is fraught with symbolism. An awakening, becoming aware of an inner truth, a spiritual revelation. Even a resurrection. But Locke’s eye isn’t meant to be “read” in the same way as Jack’s. Locke’s right eye (or, rather, “eye”) is bifurcated by a scar running vertically down “across” is center. His insight, then is “crossed” with Jack’s.

In one sense, we could say Locke’s resurrection is exteriorized as opposed to interiorized. His body has been reborn. He can walk. But is just as angry and self-oriented as before the crash, as evidenced by his casual dismissal of Michael’s injury in favor of his own self-aggrandizement in pursuing the boar. (Okay, maybe he does more than “invoke” the historical John Locke.) Not that Michael is a particular saint here, either. He’s not hunting boar to hunt boar, but to get a better idea of who Locke is. He’s doing it to impress his son. And Kate, she’s along so she can climb a tree. Her trip up the axis mundi is ill fated, however, when the monster comes along and disturbs her concentration; she drops the transceiver antenna and ends up being the doctor to Michael’s wound. So everyone, really, is using the boar hunt to achieve some other end. Which rather makes the boar hunt a metaphor. And of course the “boar” as a heraldic figure is rich in many mythologies. The Greek heroes all killed boar to prove their might and valor, or to atone for sins; in Norse culture, too, it symbolized the warrior; the white boar was a badge of Richard III. (Not sure how any of this applies to our small opera, for what it’s worth.)

Well, there is that war game that Locke plays on his lunch break, roleplaying “the Colonel” to his co-worker’s “GL-12.” Back in the Pilot Part 2 entry we made a bit of a hullaballoo about Backgammon as a metaphor for the show itself. But Locke’s game is, well, something he may have well invented. I mean, there’s a Risk board on the table, but it’s covered with generic plastic army men. Mostly, though, the scene is ironic. He chides his friend for lacking patience, even though this is not exactly one of his own demonstrable character traits, given his outbursts. Likewise, his story about Norman Croucher, a paraplegic who climbed Mount Everest, is rather apocryphal. Croucher was indeed a double-amputee renowned for his mountaineering, but he never climbed Everest.

Not sure what that has to with anything, either.

Mirror Twinning

I am more sure, however, of how this episode sets up a mirror-twin dynamic between Locke and Jack. First, of course, is the repetition of the show’s iconic opening image, implicitly linking the two characters at this point. In terms of the story, though, notice how Locke and Jack kind of trade places here. Locke was the quiet one, working on the periphery of the group, while Jack was front and center. But now we’ve got Locke stepping into a leadership role, being all extroverted, while Jack is more passive, marginalized, reflective. He denies the leadership accorded to him by Claire when he refuses to read words at the ceremony. As the fuselage burns, he sits off to the side, alone in the darkness. On top of it, Jack has started seeing things, which is paralleled with Locke’s encounter with the “monster.”

There’s another mirror-twin conceit to consider here, though, which is at the structural level of the narrative’s “discourse.” The biggest one is the shot of Locke’s foot on the beach, which is twinned out in the jungle. The shot begins with the focus on Locke’s face, then refocalizes on his foot — more evidence that the camera is in service to the focal characters, that this is a story told in “third person close.”

There’s another mirror-twin conceit to consider here, though, which is at the structural level of the narrative’s “discourse.” The biggest one is the shot of Locke’s foot on the beach, which is twinned out in the jungle. The shot begins with the focus on Locke’s face, then refocalizes on his foot — more evidence that the camera is in service to the focal characters, that this is a story told in “third person close.”

Notably, both shots are also twinned themselves, with the beach shot repeated at the beginning and end of the story, while the jungle shot bookends the “war game” Flashback that sits right at the very center of the episode.

This repetition of shots is likewise built into the Flashback structure of the episode, which features something new: a Flashback to a time on the Island. It’s Night Four of their time on the Island, but the episode begins on Day One. This is a Flashback, one that John is having when it ends with the sound of a dog barking, which is actually Vincent barking in the present. As mentioned before, Flashbacks are connected to characters via sound effects, typically diegetic ones. Anyways, it’s interesting that the first “Island” flashback is twinned, again suggesting a property of the Island itself.

And then there’s the return of repeated dialogue. The most obvious, of course, is John’s catchphrase, “Don’t tell me what I can’t do.” We get multiple mentions of “Helen” (a name meaning “beautiful” as well as evoking Greek myth) and someone telling John “you can’t.” The repetition of “Steve and Kristin,” the happy newlyweds who sat a few rows behind Claire on the plane. Other twinnings include John’s purchase of two tickets to Australia, and a subplot oriented around a second hunt. The fish hunt.

Like the Boar Hunt, the Fish Hunt is symbolic and metaphorical. It’s also deeply ironic. See, the Fish is predominantly a symbol of Faith in western culture, designated in particular by Christianity. The phrase “fishers of men” is an important one in Christianity, and makes explicit a metaphor that likens people to fish. This, of course, is exactly what happens to Charlie. He’s excited to receive attention from Shannon, so much so he’s willing to forego a fix of heroin. She wants fish. He goes fishing. In so doing, he develops a relationship with Hurley, who helps him “corner” a fish. But when Charlie returns the fish (love the deep red color) to Shannon, he quickly realizes he was just being used. Instrumentalized. “I told you I’d catch a fish,” Shannon says. Charlie is the fish. The irony, of course, is that a symbol of Faith has now been transformed into a symbol for something quite the opposite. Something like a lie.

Like the Boar Hunt, the Fish Hunt is symbolic and metaphorical. It’s also deeply ironic. See, the Fish is predominantly a symbol of Faith in western culture, designated in particular by Christianity. The phrase “fishers of men” is an important one in Christianity, and makes explicit a metaphor that likens people to fish. This, of course, is exactly what happens to Charlie. He’s excited to receive attention from Shannon, so much so he’s willing to forego a fix of heroin. She wants fish. He goes fishing. In so doing, he develops a relationship with Hurley, who helps him “corner” a fish. But when Charlie returns the fish (love the deep red color) to Shannon, he quickly realizes he was just being used. Instrumentalized. “I told you I’d catch a fish,” Shannon says. Charlie is the fish. The irony, of course, is that a symbol of Faith has now been transformed into a symbol for something quite the opposite. Something like a lie.

The Obvious Aspects of the Reveal

RICK: You misrepresented yourself–

LOCKE: I never lied.

RICK: –by omission, Mr. Locke. You neglected to tell us about your condition.

Which brings us to the Reveal. For many people, Walkabout is the episode that truly got us hooked on LOST. And that’s because it delivers the emotional goods. We come to know this man who is frustrated, angry, and alone. He’s belittled and mocked by his boss. His “girlfriend” is a “call” girl. And when we see him getting rejected for his Walkabout, it truly seems unfair and nearly incomprehensible… until the Reveal. We see Lock sitting in a Wheelchair. And then everything locks into place.

This is a Reveal that doesn’t just depend on keeping a secret from the audience. I mean, it does, the first time around, but in subsequent viewings we already know that John is paraplegic. We can appreciate all the little clues that might have tipped off a truly attentive viewer – those shots focusing on his feet, for example. Or the bedside TENS machine stimulating his legs while he talks to Helen on the phone. The story of Norman Croucher. Even the bit where Locke throws a knife into a chair (a twin chair, given Sawyer’s sitting in the second half). And the Reveal wasn’t just set up in this episode. In previous episodes we saw the Losties using a wheelchair to lug around luggage on the beach.

This is a Reveal that doesn’t just depend on keeping a secret from the audience. I mean, it does, the first time around, but in subsequent viewings we already know that John is paraplegic. We can appreciate all the little clues that might have tipped off a truly attentive viewer – those shots focusing on his feet, for example. Or the bedside TENS machine stimulating his legs while he talks to Helen on the phone. The story of Norman Croucher. Even the bit where Locke throws a knife into a chair (a twin chair, given Sawyer’s sitting in the second half). And the Reveal wasn’t just set up in this episode. In previous episodes we saw the Losties using a wheelchair to lug around luggage on the beach.

But that Reveal of the Chair, as stunning as it is, is still effective. The lie of omission has been cleared from the decks, and yet it still works. I maintain it’s because the truth revealed is so powerful. A man who could not walk, can now walk. And we can tell how deeply important this is to him. How grateful he is when he stands on his own two legs. The swelling music in the background surely facilitates this. But what we ultimately have here is a story that ends in Grace, that boon delivered to someone who doesn’t deserve it, who has in fact given up. It’s the Grace that’s powerful.

And given how the chrome finish of the Chair mirrors all that fire around it, before it fills up the entire screen, creating a juxtaposition between the Chair and Grace and yet also this imagery of Hell, I can’t even.

INTERMISSION

INTERMISSION

So we have two books to talk about for the Intermission. The first comes from the title of this episode, “Walkabout.” It’s an interesting word. As Locke says, a “walkabout” is certainly a “a journey of spiritual renewal, where one derives strength from the earth. And becomes inseparable from it.” Certainly puts Locke’s personal journey on the Island into perspective. But there’s a second meaning to word “walkabout.” To “go walkabout” also means “to be lost.” So the title of this episode functions as a mirror to the show as a whole.

It’s also the title of a book that’s been made into a movie. Walkabout by James Vance Marshall (1959), details the adventures of a brother and sister who survive a plane crash in Australia, which the girl, Mary, remembers in Flashback. So, you know, there’s a bevy of connections to LOST right there. Hell, the first words on the inside cover are “LOST AND AFRAID!”

Mary and Peter immediately struggle to survive – they have trouble just finding food and water once their meager provisions run out. They encounter, however, a young Aboriginal boy on his “walkabout,” for him a rite of passage to prove his manhood. He keeps them alive, but at the cost of his own life – he succumbs to Peter’s cold, of all things, withering because he mistakes Mary’s religious horror at his nakedness for a surety that’s he’s destined to die. The children learn just enough to make it to a fertile valley, where a couple weeks later they meet some more Australians, who direct them to Western “civilization.”

Throughout the book there are references to being lost—“somewhere in the middle of an unknown continent” as Mary imagines it. They are lost in trying to communicate with the Aborigine boy. And even staying with him, they’ll still be lost; he doesn’t know where they want to go. At one point in the story, moved to dance ritually, the boy becomes “lost” in it, and his “pantomime became reality.” “Lost” describes a missing handkerchief, a trance, and the moment before waking from sleep. And then there’s this:

Death was the Aboriginal’s only enemy, his only fear. There was for him no future life, no Avalon, no Valhalla, no Islands of the Blest. That was perhaps why he watched for death with such unrelaxing vigilance; that certainly was why he feared it with a terror beyond all “civilized” comprehension.

I highlight this not just to point out a reference to the Island, but to note the kind of implicit Eurocentrism in the writing. To be clear, writer James Marshall doesn’t exactly disparage the Australian outback; on the contrary, he obviously loves it, and the perspective of the people who live there – the scare quotes around “civilized” are genuine. Yet he is still an outsider. He still writes from a European point of view, laden with Western assumptions and values, including latent variations of racism and misogyny. Worse, he uses an omniscient point of view for the story, pretending that he does have access to the interiority of the Aborigines. But it’s more effective when he’s in Mary’s point of view, as when she holds the Aborigine on his deathbed:

It was the smile that broke Mary’s heart: that last forgiving smile. Before, she had seen only as through a glass darkly, but now she saw face-to-face. And in that moment of truth all her fears and inhibitions were sponged away, and she saw that the world which she had thought was split in two was one.

This union of opposites is, of course, the heart of alchemy. It’s a principle that extends to Mary’s musings on the afterlife, which she considers the boy’s place in Heaven to be assured, given that she knew “that Heaven, like Earth, was one.

The movie made in 1971 was only roughly aligned with the book. There’s no plane crash; the children’s father instead drives them out to the bush before committing suicide. The Aborigine boy dies under different circumstances. Mostly, though, there isn’t the same isolation from other Western people. But whereas the theatrical Walkabout was not much to write home about (apart from its cinematic beauty), the same cannot be said of Apocalypse Now, which, perfectly, announces at the beginning that “this is the end” juxtaposed over a screen of fire… just like the end of LOST’s Walkabout.

Anyways.

JACK: So, hunting boar now, huh?

KATE: Who says it’s my first time boar hunting?

JACK: Tell me something, how come every time there’s a hike into the heart of darkness you sign up?

To get to Apocalypse Now, we must first look at Heart of Darkness, by Joseph Conrad (1902), a book referenced by Jack’s dialogue, and considered a “classic” of Western literature. Like Marshall’s Walkabout, it can’t help but be problematic, which we’ll get to in a bit. In many respects, though, this is “the other side” to the Australian yarn. Beginning with its discourse, a frame story which allows a single narrator to tell the tale (to a group of fellow sailors). As such, it becomes rooted in a particular perspective, which gives it a kind of honesty – not so much in the unfolding of the story’s details, but in that those details are clearly shaped by the character himself, and as such are necessarily subjective.

To get to Apocalypse Now, we must first look at Heart of Darkness, by Joseph Conrad (1902), a book referenced by Jack’s dialogue, and considered a “classic” of Western literature. Like Marshall’s Walkabout, it can’t help but be problematic, which we’ll get to in a bit. In many respects, though, this is “the other side” to the Australian yarn. Beginning with its discourse, a frame story which allows a single narrator to tell the tale (to a group of fellow sailors). As such, it becomes rooted in a particular perspective, which gives it a kind of honesty – not so much in the unfolding of the story’s details, but in that those details are clearly shaped by the character himself, and as such are necessarily subjective.

So the story is about a sailor, Marlow, who goes up a mighty river in Africa to retrieve a Colonel Kurtz. Kurtz has made himself a god amongst the “primitives” and delivered an incredible amount of ivory for The Company, but his methods have become “unsound.” Of course this is problematic, considering Africa at the turn of the 20th Century as “savage.” Indeed, all of the portrayal of Africa indulges in a great variety of grotesque stereotypes.

The point of the book, though, is that Western culture and white men are even worse. London itself is likened to the “darkness” of the African interior. And as the self-critique it lays itself out to be, holding up a mirror to the West, I couldn’t agree more. But this must necessarily come with a caveat, namely that the “Africa” used by Conrad to describe the state of the Western soul is itself a product of the fevered Western imagination, not Africa itself.

All that said, the core of the story is still an examination of the human (or at least Western) condition, using an “exotic” location to serve as a metaphor for this “spiritual journey.” As the Russian journalist in the story (described as a sort of harlequin) explains, Kurtz has “enlarged” his mind. Nonetheless, the walkabout her isn’t exactly uplifting. Anything but.

The broadening waters flowed through a mob of wooded islands; you lost your way on that river as you would in a desert, and butted all day long against shoals, trying to find the channel, till you thought yourself bewitched and cut off for ever from everything you had known once—somewhere—far away—in another existence perhaps. There were moments when one’s past came back to one, as it will sometimes when you have not a moment to spare to yourself; but it came in the shape of an unrestful and noisy dream, remembered with wonder amongst the overwhelming realities of this strange world of plants, and water, and silence.

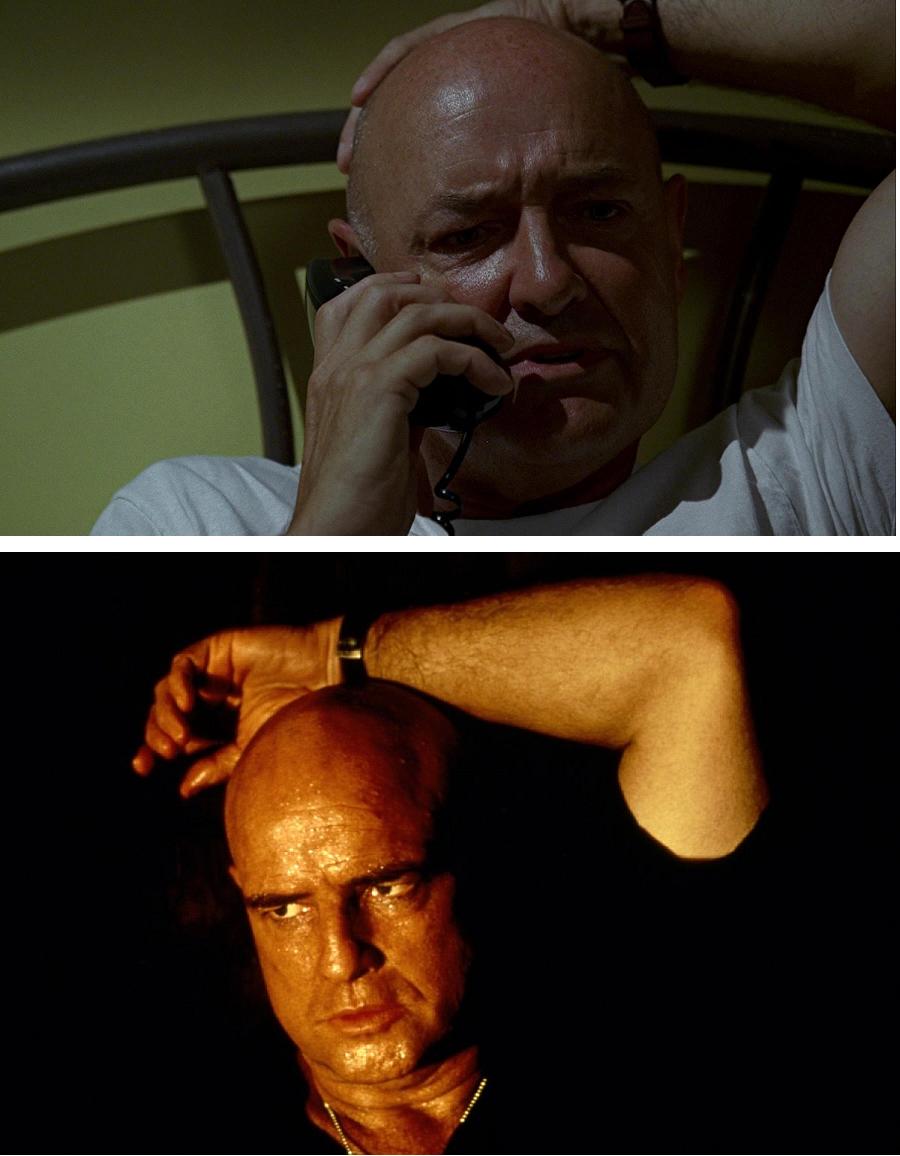

This anxiety (such as carried by John Locke) is one of several features shared in common with this episode of television. Marlow can be seen in Sayid, with their shared zeal for rivets. Locke himself, though, is called Colonel, and his head is bald, like Kurtz’s. But Locke is the one going into the jungle, like Marlow. Who goes on about “Destiny. My Destiny!” He’s the one who comes back with the sacrifice, covered in blood, not unlike the filmic version of Marlow, Martin Sheen’s Capt. Willard in Apocalypse Now. John Locke is both, then, the hunter and the hunted, the false god and the earnest disciple on his walkabout, an ultimately ironic character.

This anxiety (such as carried by John Locke) is one of several features shared in common with this episode of television. Marlow can be seen in Sayid, with their shared zeal for rivets. Locke himself, though, is called Colonel, and his head is bald, like Kurtz’s. But Locke is the one going into the jungle, like Marlow. Who goes on about “Destiny. My Destiny!” He’s the one who comes back with the sacrifice, covered in blood, not unlike the filmic version of Marlow, Martin Sheen’s Capt. Willard in Apocalypse Now. John Locke is both, then, the hunter and the hunted, the false god and the earnest disciple on his walkabout, an ultimately ironic character.

And perhaps, again, it behooves to consider that he does represent a dark heart of Western civilization, much as the historical Locke is somewhat responsible for our current predicament. For this is the heart of the madness:

If man in the state of nature be so free, as has been said; if he be absolute lord of his own person and possessions, equal to the greatest, and subject to no body, why will he part with his freedom? Why will he give up this empire, and subject himself to the dominion and control of any other power? To which it is obvious to answer, that though in the state of nature he hath such a right, yet the enjoyment of it is very uncertain, and constantly exposed to the invasion of others…

— John Locke, Second Treatise

This is exactly the sort of alienation that is rather visible in the “nature books” heretofore described. Mary and Peter have no idea of how to interact with the land, and they are so “toxic” that they end up killing their host (the unnamed Aborginal boy) with their sickness. Kurtz is so devoid of connection that he can rule through sheer brutality. In both books, there’s an “us and them” mentality assumed by the white protagonists. And we see that same kind of alienation in Locke, from his failed relationships to his cold abandonment of Michael in the jungle.

So, that was the intermission. Beyond this point, spoilers abound.

LOST Through the Looking Glass (Walkabout)

So there’s something rather strange about watching a show and already knowing what’s going to happen, especially a show that hangs its hat on mystery. We’re in the ultimate “audience superior” position regarding our relationship to the text. Except with LOST, we are still denied access to the deepest mysteries of the show, namely the nature of the Island, and secondly the nature of the Smoke Monster. To some extent this latter question is answered – we know the Man in Black has “become” a Smoke Monster, and what sorts of powers that entails, but that still doesn’t really answer our question of why his fate was “Smoke Monster” in the first place. So these are the show’s main omissions. And as described by the Walkabout tour guide (helpfully named Rick Romer) these constitute lies.

That this aspect of the text is clarified in a story that pivots on a Reveal, well, it’s understandable that people would take such a structure as a promise for the whole text.

So, omissions. We don’t actually see the Monster yet, only its effects, from its tearing down of palm trees to the profound effect on Locke. Yet this eliding of Smoky fits perfectly with the sort of omission that Locke practices. And indeed, there’s plenty here to suggest that Locke’s aspect was the perfect choice for Smoky to take. Certainly the structure and positioning of certain Flashbacks contributes to this. Locke’s first Flashback is to the Island, not to before the crash. His beatitude is oriented towards the Island, towards rising up on that beach. The slight smile on his face as the Fuselage burns, and the fire rising up to engulf the whole screen, yeah.

But a very important note occurs in a most peculiar Flashback. We’ve noted that the Flashbacks have all shared a principle of connectivity to the characters having them. Here, though, we get a Flashback that violates that principle. It comes on the tail of the scene on the beach where Locke reveals that he’s got a silver suitcase full of knives:

LOCKE: Boar’s usual mode of attack is to circle around and charge from behind, so I figure it’ll take at least three of us to distract her long enough for me to flank one of the piglets, pin it, and slit its throat.

SAWYER: And you gave him his knife back?

JACK: Well, if you’ve got a better idea.

SAWYER: Better than the three of you wandering into the magic forest to bag a hunk of ham with nothing but a little bitty hunting knife? Hell no, it’s the best idea I ever heard.

(Locke opens up his case of knives)

HURLEY: Who is this guy?

It’s on Hurley’s line that we hard cut to Flashback, where Locke is sitting at his desk. This is interesting – there’s no transition here. So the Flashback stands out like a sore thumb. Furthermore, there’s no transition back to the Island, either. Instead we cut to black (a commercial break) – but there is a sound effect. A transition to black – the sound effect is the ticker tape of an adding machine. It’s also one of the sound effects of the Smoke Monster. The Man in Black, who ends up playing Locke – that’s a lovely hidden depth to the structure here.

Consider, though, the role that Hurley plays. Hurley asks the question, and given that Hurley becomes the Island protector, a Jacob figure, he once again demonstrates a kind of meta-narrative authority in getting a Flashback (that isn’t his) to come and answer one of his questions. Given that Smoky also has “narrative authority” – when the Monster approaches Locke in the jungle, we get a shot from Smoky’s interior POV – there’s a nice bit of symmetry to how Hurley and Smoky seem to bookend the otherwise unconnected Flashback.

All of which is to say, some rather unexpected things make more sense now, knowing how the narrative will ultimately unwind itself. Of course, this could just be lucky coincidence. It remains to be seen if the principles gleaned from the Exegesis will hold throughout the small opera. But here, at least, we seem to have very good evidence that The Powers That Were were perhaps more aware of how they wanted the show to play out than even they have admitted to.

In which case, perhaps the faith of fandom in the show really was justified? If so, though, then there’s equally evidence that TPTW actively obfuscated the show’s mysteries as the show came to a close, in the most clever of ways – by showing rather than telling. Which is exactly what the Reveal in Walkabout promised.

Fish Redux

Fish Redux

CLAIRE: Excuse me, your name’s Sayid, right?

SAYID: Yes.

CLAIRE: I just found this. It’s got your name on it.

SAYID: I thought I’d lost this. Thank you.

It’s a small moment in the narrative. Claire finds an envelope with Sayid’s name on it. Inside are pictures of a woman. But it’s from the dialogue that open up this scene as a “mirror” of the show, which we get any time the word “lost” appears in the text. So let’s take a closer look at what’s happening here.

Structurally, it sits between a Fish Scene and a Jack/Rose scene. It’s a transition, in other words, from a moment of false faith to one that is pure. But here I must apologize for the Exegesis, for it never covered what the scene with Jack and Rose actually represented. The Jack/Rose interactions all come on the heels of the Fish Scenes, from Shannon recruiting Charlie to catch a fish, to Charlie fishing with Hurley, to Charlie realizing that he was the fish all along.

Jack and Rose are the balancing act to that con artistry. Everything between Rose and Jack is honest, and motivated by concern for others. Notice, though, how they spend their time looking out to sea. To the water. A reflective surface. They are pointed away from the Island, whereas John Locked is pointed to the interior. And then there’s the content of their interaction – it’s the Memorial Service that rouses Rose from her reflections. It is here that we see Rose’s faith expressed – her husband isn’t dead, contrary to Jack’s belief. We know, with our magical foresight, that she is right. Her faith is pure. Alongside that faith, I should note, is the anecdote about her husband’s Ring. The Circle.

Anyways, that the scenes with Rose and Jack are meant to be juxtaposed with Charlie’s fish hunt is evidence by a lovely bit of dialogue:

Anyways, that the scenes with Rose and Jack are meant to be juxtaposed with Charlie’s fish hunt is evidence by a lovely bit of dialogue:

ROSE: He started having me hold onto his wedding ring whenever we took a plane trip. Always wore it around my neck for safe keeping. Just until we landed. You know, doctor, you don’t have to keep your promise.

JACK: Promise?

ROSE: The one you gave me on the plane. The one you made me—to keep me company until my husband got back from the restroom. I’m letting you off the hook.

Jack kept his promise in good faith, but now Rose is “letting him off the hook.” Like a fish that’s been set free, back into the water of the sea. Now, as I said before, the triptych Rose/Jack scenes come on the heels of the triptych of Fish Hunt scenes. And by that, I mean immediately. Except for the middle one, where Sayid receiving an envelope of memories has been spliced between the scene detailed above and the bit where Charlie fishes with Hurley.

The splice maintains a certain structural elegance to the proceedings. But there’s more going on under the hood. Because now we know what the significance of that envelope is to Sayid. It contains pictures of his lover, Noor. Noor – or more properly “N?r” – is a word for Light in Arabic, Persian, and Urdu. But this isn’t any ordinary light, because it’s also used greatly in the Quran to describe the Divine. This understanding of Light surely informs what we’ll find in the Mother’s cave. But we’re getting ahead of ourselves. For now, it suffices that the Divine has been invoked upon Sayid’s opening of the envelope. And because the photographs ultimately represent Sayid’s memories, we now have a juxtaposition of Memory and Divinity as well. Which sheds a very different light on all these Flashbacks that we’ve been seeing. Especially given that a “flash” also implies an instance of light.

So, this envelope of divine memories, this is what Sayid “lost.” LOST, therefore, is really all about this. And again, this occurs in a story called “Walkabout,” a word which explicitly refers both to “being lost” and to some kind of “spiritual journey.”

We Have To Go Back

There are several tidbits in the dialogue to account for, which continue to point at a circular structure to LOST, to a kind of Eternal Return.

KATE: I’m sorry. I guess I should’ve gotten a warranty.

SAYID: I suppose I’ll just try again. Of course, I have no welding iron, no rivets, scorched wiring. And it seems I must continue to lie to anyone who asks me what it is I’m actually doing.

KATE: Sayid, I’ll try it again.

SAYID: We’ll try it again.

In this scene, Kate has returned the broken antenna to Sayid. Of course the repetition of “try again” is delicious, given that “try again” is pretty much the meaning of repetition. I like how Sayid complains about lying, one of the ongoing themes at the beginning of our small opera; Kate’s mention of a “warranty” is the antidote to that. The mention of “rivets” echoes a concern of Marlow in Heart of Darkness. Mostly, though, if the Losties truly are doing things over and over again, in some kind of Eternal Return, this turns out to be a very funny exchange.

LOCKE: Boar’s usual mode of attack is to circle around and charge from behind, so I figure it’ll take at least three of us to distract her long enough for me to flank one of the piglets, pin it, and slit its throat.

Locke says that a boar’s mode of attack is to “circle around and charge from behind,” but this is a lie. Boars just charge. Which we actually saw when it gored Michael. Locke’s speech, apocryphally speaking, is an excuse to get the word “circle” into the dialogue.

RICK: I can get you on a plane back to Sydney on our dime. That’s the best I can do.

LOCKE: No. I don’t want to go back to Sydney. Look I’ve been preparing for this for years.

“Go back” comes the moment before the Wheelchair reveal. And of course Locke doesn’t want to “go back.” He’s had a pretty miserable life. Why on earth would he ever want to go back? But he will have to. He’s been left behind.

JACK: We don’t have time to sort out everybody’s god.

CHARLIE: Really, last I heard we were positively made of time.

Probably my favorite quote from the whole episode. Here it is established that Time and Divinity have some kind of equivalence. The conversation, though, is about proper funeral rites. It’s about Death.

Apocrypha Now

This is just a little something. In the memorial service scene, Claire reads out a bunch of names. One of them is a man, Harold, who was sitting in 23C. Jack’s seat was 23A. Yet in all the airplane crash scenes, we never see another man sitting next to Jack. In fact, Jack ends up sitting in 23C while he’s comforting Rose, when the plane starts to go down. Funny, that.

Another name read by Claire: Judith Martha Wexler. Martha means “lady,” nothing remarkable there. Wexler means “money changer,” which is slightly more interesting. It actually expresses an alchemical principle, that of equal exchange. To change money is also to “translate” one type of currency into another. I only bring this up now because, due to the magic of foresight into the Exegesis, this is an alchemical principle that will figure rather strongly in future readings.

And then there’s Judith. Her name means “praised,” but what’s really interesting about her is that she has her own Book of Judith, another deuterocanonical book in the Christian tradition. Which is to say, another source of Apocrypha. Judith saves Israel from the Babylonian king Nebuchadnezzar by charming his general Holofernes before decapitating him. Now there’s a lovely image. It’s actually been depicted by many great artists, from Botticelli and Caravaggio to Michelangelo’s Sistine Chapel. Pretty impressive for something “apocryphal.”

The other thing that’s interesting about the Book of Judith is its structure, which follows a “chiastic pattern” or “ring structure” – a kind of mirror pattern where the procession of text’s motifs repeats itself going backwards from the center, with slight variation. Kind of like A-B-C-c-b-a. Inverted parallelism. The word “chiastic” derives from chiasmus, which means “crossing” and refers to the shape of the letter X. (Ah, an X motif!) We’ll be addressing this concept in more detail when we get to The Moth.

The other thing that’s interesting about the Book of Judith is its structure, which follows a “chiastic pattern” or “ring structure” – a kind of mirror pattern where the procession of text’s motifs repeats itself going backwards from the center, with slight variation. Kind of like A-B-C-c-b-a. Inverted parallelism. The word “chiastic” derives from chiasmus, which means “crossing” and refers to the shape of the letter X. (Ah, an X motif!) We’ll be addressing this concept in more detail when we get to The Moth.

Oooh, and there’s another reversed image!

CHARLIE: If he’s so eager to burn the bodies why are we waiting until sundown?

KATE: He’s hoping someone will see it.

The image that’s reversed is the delivery of Kate’s line. I wonder if this a “through the looking glass” moment, in the sense of a breach of the 4th Wall. The Powers That Were, were they hoping someone would find this stuff?

Coda

Coda

Finally, just to loop back around to that opening image of John’s opening eye, and in particular the vertical line crossing his eye. The thing about that line is that every day the makeup department has to recreate it anew. Each time, though, they have to do it just a little bit differently, to suggest that the wound is healing. Eventually it will become a scar.

In theatre makeup, the motif of a vertical line crossing through the eye is most obvious in the figure of the mime. To mime something is act it out, to imitate. As such, there’s an implication of the simulacra in the mime. Historically speaking, the modern visual motifs of the mime derive from Jean-Gaspard Deburau, a French mime of the early 19th Century. In particular, through his work with the Commedia dell’Arte character known as Pierrot, the original sad clown, naïve, insular, frustrated, isolated, estranged. John Locke, in other words.

On a more abstract level, though, Locke’s eye reminds me of the musical symbol of the Coda. The Coda is the tail-end of a musical passage, which is jumped-to after a series of repetitions or variations. The Code functions like a musical denouement, recapitulating the song in such a way that a listener can “look back” on the piece and “take it all in,” in order to “create a sense of balance.”

This motif makes me wonder about all the Eye openings littered throughout LOST. In particular, if they are “entry points” for a consciousness to “go back” to, possibly upon death. We certainly get that suggestion from the continuity of the show’s first image (Jack’s Opening Eye) and its final one (Jack’s Closing Eye). And especially given that the Opening Eye of Walkabout is, indeed, a Flashback.

Now there’s a rabbit hole for you.

November 17, 2015 @ 8:18 am

Another brilliant, insightful and interesting reading Jane. I have to take exception to this comment though –

the theatrical Walkabout was not much to write home about (apart from its cinematic beauty)

The films of Nicholas Roeg, including The Man Who Fell to Earth, Performance, Insignificance and of course Walkabout all demonstrate a unique and innovative use of editing and direction using cross cutting, juxtaposition and most importantly a way of shuffling chronology that almost approaches the Burroughsian ‘cut up’ technique to tease meaning from random associations in the text. In this regard I’m surprised you don’t make more comparison between the movie and Lost. Sight and Sound’s James Bell called Walkabout “a piece of ‘pure’ cinema through the use of mesmerising images of the landscape, dramatic shifts to the subjective points of view of its characters, and the jarring juxtapositions in editing for which he [Roeg] would become well known.”

I agree with you about this exchange and think it is key

JACK: We don’t have time to sort out everybody’s god.

CHARLIE: Really, last I heard we were positively made of time.

Also as I mentioned William Burroughs

…who was sitting in 23C. Jack’s seat was 23A. Yet in all the airplane crash scenes, we never see another man sitting next to Jack. In fact, Jack ends up sitting in 23C

I’m sure you’re aware of Burroughs and the 23 mystery but here’s a link and an uncannily apposite quote –

“I first heard of the 23 enigma from William S Burroughs…According to Burroughs, he had known a certain Captain Clark, around 1960 in Tangier, who once bragged that he had been sailing 23 years without an accident. That very day, Clark’s ship had an accident that killed him and everybody else aboard. Furthermore, while Burroughs was thinking about this crude example of the irony of the gods that evening, a bulletin on the radio announced the crash of an airliner in Florida, USA. The pilot was another Captain Clark and the flight was Flight 23”

https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/23_enigma

The scar on Locke’s eye could also suggest the crosshairs of a gun-sight. Visually positioning him as far sighted, a hunter who is target or goal oriented and demonstrably not ‘blinded’ by the events of the crash. In fact, as we later discover – as a kind of reverse or mirrored injury, his actual pre-crash disability has been miraculously cured; suggesting that he has been touched by the divine or the uncanny.

November 17, 2015 @ 9:03 am

Oooh, you’re right, I missed a trick on the Walkabout movie.

Yes, cross-hairs! But Locke isn’t just the far-sighted hunter, with deeper insight into the Eyeland than the rest of his cohort. He also has those cross-hairs trained on him. He’s been marked for another purpose, and for a very long time.

This kind of makes Locke a Mirror Man.

November 17, 2015 @ 10:02 am

Nice. Mirror Man.

I can’t remember where LOST and l parted company but I think it was around season three. You’ve piqued my interest now and I’m really going to have to make time for a LOST re-watch.

November 17, 2015 @ 9:25 am

I think you’re overstating the extent to which John Locke, the philosopher, is really the poster boy for the modern right that the modern right would like him to be. There is nothing I think in his philosophy that rules out spending on a welfare state, for example, and quite a lot that would justify it. (We have he says in the state of nature a duty to preserve other people’s lives which takes second place only to the duty to preserve our own.)

I think the orientalist reading of Heart of Darkness that Achebe objects to is a product of Western attempts to depoliticise or dematerialise it. Conrad was an associate of Casement in Casement’s project to document the atrocities in the Congo. The positioning of Africa as Other is repeatedly made problematic: in particular, there’s one instance where it occurs to Marlowe that the Congolese might regard the sound of drumming that seems so savage to him in the way that the English regard church bells. That is not the only instance in which the Congo is structurally identified with England. The book presents the position of Africa as the Other as a product of Marlowe’s ignorance (and of the Belgian atrocities) rather than an essential quality.

November 17, 2015 @ 10:40 am

So brilliant. I was hooked from the Pilot, but Walkabout really is the first episode to fully deliver on the promise of the show (even while making bigger promises as you point out). It’s rightly considered a classic, and you did it justice.

The connections between Locke & the Smoke Monster are so glaring in hindsight. And I’m LOVING the repetition of Hurly’s narrative control. I think later of the motif of “Hurley’s handouts” – of being the guy who takes care of everybody and “makes them feel safe” – and he really is immediately positioned as the antithesis to Locke the (for better or worse) consummate individualist.

I’m finding myself eagerly anticipating these analyses.

November 19, 2015 @ 1:28 am

Good stuff! It is really worth to go through this article. I appreciate you for sharing your viewpoints on a relevant topic like this. I impressed with the valuable points you have shared. Looking forward for more updates!

February 22, 2016 @ 10:10 am

I am a writer working with custom essay writing service it provided by the quality essay papers to all students that is school students, research students and doctoral students.

April 16, 2016 @ 7:37 am

Thanks for sharing this info.Good articles.I always find here many useful things

May 10, 2016 @ 8:03 am

Hi! Thanks for this post! Keep writing!

June 13, 2016 @ 7:44 am

I am impressed with the image depicting an open eye with vertical line. Hats off to the artist.

August 22, 2016 @ 2:37 pm

I was really impressed to visit your blog and read all the stories. Fascinating adventures, keep on sharing more.

My page is http://www.grand-essays.com/.

November 12, 2016 @ 12:29 pm

Very well written and detailed story which is very close to the reality of life.

November 17, 2016 @ 10:08 am

I did not watch this episode but it looks very interesting and full of thrill & adventure.

December 22, 2017 @ 7:07 pm

Good post.