Lost Exegesis (White Rabbit) — Part 1

White Rabbit really does represent a rabbit hole for the series. The Pilot was, well, the pilot, the story to get you hooked. Tabula Rasa was what an ordinary episode of Lost television might look like, and Walkabout showed off all kinds of technical and emotional chops. And all of them played with certain intriguing aesthetics. This episode plays off each of the previous ones, demonstrating a certain structural and thematic continuity, while continuing to broaden the chasm gaping open upon the show’s Mysteries.

We should start with the Flashbacks and the Mirrors. Two episodes in a row now, we’ve begun with an Opening Eye in the focal character’s Flashback. This is an example of continuity, a way of visually juxtaposing two characters, in this case Jack to Locke. It also makes three of five episodes opening with the same image – this is now a part of the show’s overall language, a language that is largely symbolic or at least unspoken (which we’ll get to, I promise).

We’ll get to the Locke/Jack stuff in a bit, but first let’s take a longer look at these Flashbacks. Jack’s first is when he’s sitting on the beach, presumably meditating on the time when Mark Silverman got “jumped” by a couple of bullies. Jack tries to change what’s happening, but his efforts are useless – he gets punched in the eye, and the screen goes blank, filled in with the cries of what’s happening now on the Island, which is Charlie shouting Jack’s name while someone drowns at sea. Jack tries to save the drowning woman, but only comes back with Boone.

So there’s an obvious parallel here about the futility of Jack’s actions. Given the iconography in the other Flashbacks, though, one thing that might go unnoticed in this mirroring is what’s actually in the dialogue – the boy Jack tried to save when he was just a kid was named “Silverman.” A reflective surface, a mirror, and entirely symbolic. Which we only learn in the next Flashback, in what’s quite possibly the most important scene in Jack’s character development, the talking to he gets from his father.

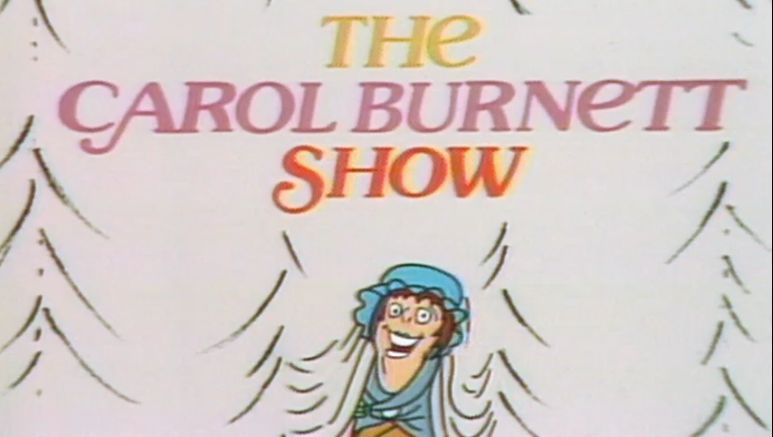

FATHER: I had a boy on my table today. I don’t know, maybe a year younger than you. He had a bad heart. It got real hairy, real fast. And everybody’s looking at your old man to make decisions. And I was able to make those decisions because at the end of the day, after the boy died, I was able to wash my hands and come home to dinner. You know, watch a little Carol Burnett, laugh till my sides hurt. And how can I do that, hmm? And even when I fail, how do I do that, Jack? Because I have what it takes. Don’t choose, Jack, don’t decide. You don’t want to be a hero, you don’t try and save everyone because when you fail… you just don’t have what it takes.

Jack’s father tells a tale of failure – and failing is just what we’ve seen Jack experience twice in a row. Jack isn’t good at failing, as his father says. He doesn’t have what it “takes” as his father puts it. But what is this, “what it takes?” Jack invokes that phrase again during his big chat with Locke in the heart of the jungle, but what is Jack’s dad actually talking about?

From Jack’s perspective, “what it takes” is whatever’s necessary to succeed. He wasn’t able to save Mark Silverman, and he wasn’t able to save the drowning woman, Johanna; he doesn’t have what it takes. And when he fails, he takes it personally; he’s motivated by compassion, in large part, because when he fails, it hurts. But what the father is really is getting at has nothing to do with skill. He’s talking about being able to laugh watching Carol Burnett at the end of a day of failure. What he’s talking about is the ability to let go. Letting go is what it takes. A lovely union of opposites.

From Jack’s perspective, “what it takes” is whatever’s necessary to succeed. He wasn’t able to save Mark Silverman, and he wasn’t able to save the drowning woman, Johanna; he doesn’t have what it takes. And when he fails, he takes it personally; he’s motivated by compassion, in large part, because when he fails, it hurts. But what the father is really is getting at has nothing to do with skill. He’s talking about being able to laugh watching Carol Burnett at the end of a day of failure. What he’s talking about is the ability to let go. Letting go is what it takes. A lovely union of opposites.

Sorry, I digress. About the mirrors, I mean. There’s another mirroring here, namely that Jack’s got a black eye. Back in Pilot Part 2 we saw Locke holding up black and white Backgammon pieces — he held them up by his eyes, but he’s got black on the right instead of on th left. Anyways.

There’s also a remarkable continuity in the use of Flashbacks. The first (Jack’s failure) is twinned with an Island event. The second, that speech with the father, is juxtaposed with Hurley asking Jack why he’s “not deciding anything” – i.e., not stepping into a role of leadership. Both these Flashbacks feature or invoke Silverman. The next one begins with a reflection of Jack on the window while it’s raining outside (hmm, water and reflective surfaces, hmmm) and his mom commands him to fetch his father from Australia. This is juxtaposed with Jack searching for his father in the jungle, creating another thematic thread between the Island and Australia. Within the third Flashback, we’re also treated to that “mirror twinning” of dialogue that predominated in Pilot Part 2:

MOTHER: Your father’s gone, Jack. Did you hear what I said? He’s gone, Jack.

JACK: He’ll be back.

MOTHER: This time it’s different. I want you to bring him back.

After repeating herself with “gone, Jack,” she repeats the word “back” from her son.

After repeating herself with “gone, Jack,” she repeats the word “back” from her son.

JACK: He hasn’t talked to me in two months, Mom.

MOTHER: You haven’t talked to him in two months.

JACK: He doesn’t want me to bring him back, trust me. Let one of his friends.

MOTHER: He doesn’t have friends anymore. Why do you think that is? He was right about you.

JACK: Right about what?

MOTHER: You don’t understand the pressure that he’s under.

JACK: I understand pressure.

The interplay continues with “two months,” “friends,” and “right about,” and notice that it’s not just Mother repeating Jack – he, too, repeats her. It’s only when we get to the very end of the scene that we get a break in the pattern:

JACK: Where is he?

MOTHER: Australia.

This is probably just a coincidence, but after more Jack running through the jungle, the next scene is about the Australian woman passing out. Not that she would have any connection to Jack or his father – she’s just there to provide concrete urgency to the situation of running out of water.

The fourth flashback is in a hotel room, and features a lovely shot of Jack turning around in front of a mirror adorned with an X motif lattice (which I remembered thanks to the “Judith” reference we got with Walkabout). This scene is about Jack playing detective, trying to find out what his father’s been up to. He finds a lot of alcohol in the suite. He also finds Hydralazine, which is used to treat high blood pressure and heart disease. Remember the big speech, and the boy who died of a bad heart? Meanwhile, on the Island, we’ve got Jack trying to find his father.

In the fifth Flashback, the transition is from Jack sitting by a camp fire. We go back to a coroner’s wing at a hospital, with all kinds of silvery reflective surfaces, where Jack finally finds the corpse of his father, who died of a heart attack. Jack begins to cry. And when we return to the Island, Jack is now crying by the camp fire. There’s an emotional continuity here, which strongly suggests (again) that the Flashbacks are something happening to the characters – they are memories. And indeed, there’s an emotional continuity or mirroring to all the flashbacks here, given they directly relate to what Jack’s experiencing on the Island. Like in the final flashback, when Jack finds a coffin at the Caves, he flashes back to convincing the woman at the airport to let him bring his father’s corpse home. But he doesn’t find his father’s corpse. All he finds is water.

to what Jack’s experiencing on the Island. Like in the final flashback, when Jack finds a coffin at the Caves, he flashes back to convincing the woman at the airport to let him bring his father’s corpse home. But he doesn’t find his father’s corpse. All he finds is water.

Water

So obviously there’s a lot going on with Water in this episode. It’s so significant it’s a major plot point – everyone needs water to survive, and the Losties are running out. I would argue that this only scratches the surface – for, after all, water itself is a reflective surface; it too can function as a mirror.

There are other juxtapositions with Water we should focus on in this episode. First, we see Water as a place of death, when Joanna drowns, and despite Jack’s efforts all he can come back with is a Boone. It’s the sound of ice in a drink that marks the big Father/Son speech in the second Flashback, and after the fifth, when Jack’s weeping is interrupted by that sound as the figure of his father passes behind him on the Island. Hell, Jack’s father is standing in the Ocean when Jack first sees him this episode. And as we said before, Jack never catches his father – he is instead led to find water. He finds a waterfall. In one of the pools, a drowned doll, an echo of Joanna. Yeah, water is a mirror.

But there’s a deeper meaning to this juxtaposition of Jack’s father and Water. And again it’s something we learn from the dialogue, from the naming conventions of the show. We’ve already established through the figure of John Locke that naming conventions are important. It’s here, in White Rabbit, that we learn Jack’s last name: Shephard. Which means his father is a Shephard, too – the Doctor at the morgue says the body was found in an alley in King’s Cross, for god’s sake. All this invokes a particularly Christian mythology – Jack’s search for his father is a metaphor for the spiritual search for God. But Jack doesn’t find his father, doesn’t find God, he only finds water. So I’m going to go out on a limb here and say that Water in LOST is symbolic of faith. Let’s see where that gets us.

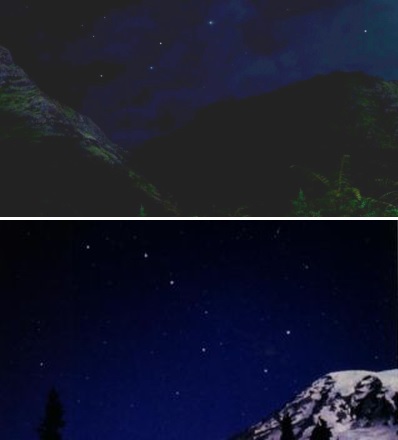

After Jack bashes his father’s empty coffin at the Caves of Water with a silver bat, we cut to a shot of the stars over the mountains. The asterism is familiar. It’s that of the Big Dipper, in the constellation of Ursa Major. There’s just one big problem with this shot. The stars are reversed.

After Jack bashes his father’s empty coffin at the Caves of Water with a silver bat, we cut to a shot of the stars over the mountains. The asterism is familiar. It’s that of the Big Dipper, in the constellation of Ursa Major. There’s just one big problem with this shot. The stars are reversed.

We’re going to talk a lot about mirrors and twinning in the course of Lost Exegesis. This episode is one of the reasons why. Now, mind you, of course it’s easy to just say that the Big Dipper reversal was an accident. That there’s nothing here to actually see. But we don’t know what it or is not intentional. We do know, however, that in tens of thousands of years, the asterism itself will change shape, with the handle of the Dipper becoming the Bowl, and vice-versa. Neat.

We also know that this isn’t the only reference in the episode to the stars. At the beginning of the final act, right after the commercial break on the heels of the Big Dipper shot, we open with a shot of the stars as the camera pans down to the Beach camp. As it turns out, this shot is a duplicate of one they used in the Pilot episode. Which is to say, it’s a twin.

And then there’s a lovely earlier in the episode that begins with Kate and Claire sharing water, in which we get speculation about missing hairbrushes before we get the following very interesting conversation:

CLAIRE: Can I—can I ask you something?

KATE: Sure, shoot.

CLAIRE: Are you a Gemini?

KATE: Yeah, I am.

CLAIRE: I thought so. Restless, passionate. You know, everyone thinks astrology’s just a load of crap but that’s just because they don’t get it. I can do your chart if you want to?

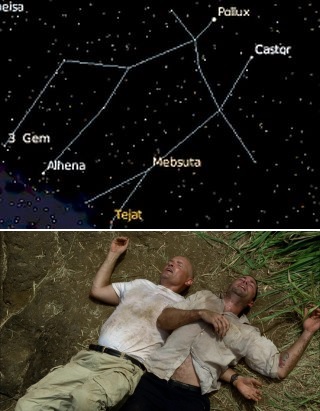

We’ll return to this scene in the Looking Glass portion of the essay, but for now let’s just focus on Gemini. Gemini is one of the twelve houses of the Zodiac in western astrology, but this itself is of course based on the stars. The constellation of Gemini, then, is of interest. “Gemini” is the word for “twins” in Latin, which is why that constellation bears that name:

The story of the Twins in Greek mythology is an interesting one. Castor and Polydeuces were twin brothers, fraternally – Castor’s father was a mortal king, while Polydeuces’ was Zeus, who bedded Leda while disguised as a Swan. When Castor eventually died, Polydeuces insisted on sharing his immortality with his brother, and so they’d take turns between immortality and death, or the heavens and the underworld. The sign of Gemini itself, then, symbolizes the union of immortality and death, of eternity and finality.

The story of the Twins in Greek mythology is an interesting one. Castor and Polydeuces were twin brothers, fraternally – Castor’s father was a mortal king, while Polydeuces’ was Zeus, who bedded Leda while disguised as a Swan. When Castor eventually died, Polydeuces insisted on sharing his immortality with his brother, and so they’d take turns between immortality and death, or the heavens and the underworld. The sign of Gemini itself, then, symbolizes the union of immortality and death, of eternity and finality.

So it’s very interesting that Jack and Locke recapitulate the iconography of Gemini after Locke rescues Jack from his cliffhanger, which brings us back to the mirror-twinning of their opening-eye shots in back-to-back episodes. Both run into the jungle looking for a Shephard. Jack runs into the jungle not knowing where he’s going; Locke runs into the jungle knowing exactly where to look. And whereas Jack doubts his ability to lead, Locke is quite sure of it, finds it obvious.

It’s in the jungle that we get yet another great speech, this time between Jack and Locke. Again, the element of Water is signified – when Jack asks how the people back at the beach are doing, Locke says they are “thirsty.” When Locke asks Jack for a doctorly self-diagnosis, the first cause for “hallucination” that Jack lists is “dehydration.” And when Locke leaves Jack on his own, it’s to go “find some more water.” Hell, the very first image of this scene is one of collecting a drop of water from a leaf, in extreme closeup. So let’s test our hypothesis and see if this conversation is actually about Faith:

JACK: How are they, the others?

LOCKE: Thirsty. Hungry. Waiting to be rescued. And they need someone to tell them what to do.

JACK: Me? I can’t.

LOCKE: Why can’t you?

JACK: Because I’m not a leader.

LOCKE: And yet they all treat you like one.

JACK: I don’t know how to help them. I’ll fail. I don’t have what it takes.

Yeah, right off the bat, we get Jack expressing a lack of faith in himself, which is being countered by Locke. (We also get another invocation of “others,” but that’s for another time.) What’s interesting, then, is that Locke seems to equate the “lack of faith” in the thirsty others with not having a leader. This is an equating of Faith with Authority. Which is common enough, though obviously problematic. It’s not presented as problematic in this scene, though.

Locke has to ask Jack twice why he’s “out here” in the jungle. At first Jack says he’s going crazy (again, an expression of faithlessness in himself) which Locke immediately negates. Then Jack says he’s chasing someone, and we get Locke’s titular invocation of the White Rabbit. We’ll get into the symbolism of the White Rabbit during the Intermission, but for now let’s reflect on the fact that for Jack to be chasing his father into the jungle at all is a tacit admission on his part that he at least wants to be seeing what he’s seeing. He doesn’t dismiss his father as a hallucination. His emotions are real. And sure, Jack has trouble letting go, but it’s interesting that when Jack finally does let go and lets himself cry by the campfire, only then does Grace come in the form of his Father leading him to Water. The White Rabbit is, ultimately, a symbol of Faith.

JACK: I’d call it a hallucination. A result of dehydration, post traumatic stress, not getting more than two hours of sleep a night for the past week. All of the above.

LOCKE: All right, then. You’re hallucinating. But what if you’re not?

JACK: Then we’re all in a lot of trouble.

Again, just to point out the position of “dehydration” in the list. Also, notice how Locke dismisses the “rational” argument in favor of a more faith-based interpretation. Jack, of course, finds this prospect absolutely problematic. But Locke counters that pessimism:

LOCKE: I’m an ordinary man, Jack, meat and potatoes, I live in the real world. I’m not a big believer in magic. But this place is different. It’s special. The others don’t want to talk about it because it scares them. But we all know it. We all feel it. Is your white rabbit a hallucination? Probably. But what if everything that happened here, happened for a reason? What if this person that you’re chasing is really here?

JACK: That’s impossible.

LOCKE: Even if it is, let’s say it’s not.

JACK: Then what happens when I catch him?

LOCKE: I don’t know. But I’ve looked into the Eye of this Island. And what I saw was beautiful.

So obviously we have the invocation of the Island’s “Eye” and Locke’s beatific expression as he describes it, the look of someone who’s had a religious conversion. More important is how Locke refuses to doubt Jack’s vision. What if that man Jack is chasing is really there? What if everything happens for a reason? Again, it’s an expression of faith.

It’s also, I should note, a potential extradiegetic commentary – instructions on how to read the show itself. Which makes this, possibly, words from the showrunners as well as the character. For example, we in the audience are given permission to consider that Jack’s father isn’t really dead, and what kind of story that would necessarily entail – like, it would take one hell of a conspiracy for Jack’s father to fake his own death. Or the Island would have some kind of special properties to resurrect the dead Shephard. Likewise, the notion that “everything happens for a reason” is an encouragement to read Lost in a certain “paranoid” style, of looking at every detail for potential meaning.

And it’s not like this kind of reading of the show doesn’t pay off – already we’ve gleaned much from looking at certain details, like the literary references and the naming conventions, and we’ve already identified an aesthetic of mirror-twinning.

If so, however, the plot seems to suggest that we won’t find the “fathers” or “creators” of the show by chasing such white rabbits. Instead we’ll find something else. Something that is actually preciously, and more crucial to our survival than identifying the next Creator, the next Shephard, the next Leader. Not that Jack isn’t a good leader, as his big speech to the Losties demonstrates:

JACK: Leave him alone! It’s been six days and we’re all still waiting. Waiting for someone to come. But what if they don’t? We have to stop waiting. We need to start figuring things out. A woman died this morning just going for a swim and he tried to save her, and now you’re about to crucify him? We can’t do this. Every man for himself is not going to work. It’s time to start organizing. We need to figure out how we’re going to survive here. Now, I found water. Fresh water, up in the valley. I’ll take a group in at first light. If you don’t want to come then find another way to contribute. Last week most of us were strangers, but we’re all here now. And god knows how long we’re going to be here. But if we can’t live together, we’re going to die alone.

The big “Live Together, Die Alone” speech. Interesting words in there, like “save” and “crucify” and “first light” and “god knows.” But there’s also a philosophy being expressed here, one that’s distinctly socialistic. There’s none of the pessimism of Jack’s father, but likewise none of the wide-eyed optimism of the spiritual Locke. It’s a repudiation of capitalism (“every man for himself is not going to work”) and instead an emphasis on a social good. The speech is littered with references to “we,” and in the middle, when it gets to “I found water” he immediately invokes the group again, and gets back to encouraging everyone to contribute; Jack isn’t making himself out as a great man, even though he’s being one. What a startling conclusion, a startling union of opposites.

Intermission

We’ve got a great show for you tonight – five wonderful pieces that may not look like they go together, and two that probably should count as one, but it’s the fifth episode so I’m being lenient. Regardless, it’s one of the key features that’s widely overlooked in LOST, its intertextuality (which is the inter-mission of this segment). Not that I blame anyone – the show is so overloaded with references it’s a rather daunting task to track them all down and actually, you know, read them.

We’ve got a great show for you tonight – five wonderful pieces that may not look like they go together, and two that probably should count as one, but it’s the fifth episode so I’m being lenient. Regardless, it’s one of the key features that’s widely overlooked in LOST, its intertextuality (which is the inter-mission of this segment). Not that I blame anyone – the show is so overloaded with references it’s a rather daunting task to track them all down and actually, you know, read them.

We start with something that’s likely apocryphal; it is, after all, a tenuous visual connection. But I am terribly reminded of John Millais’s Ophelia, a painting depicting her off-stage death in Hamlet. Granted, the orientation of the painting and the shot are perpendicular to each other, and yet there’s something awfully poignant about the drowned doll that Jack finds in the caves. Which could be simply symbolic of Joanna’s drowning off-shore.

If it is just so, then the dolls represent the Losties themselves, who will become Jack’s “children” when he steps into leadership. Which is rather patronizing, but then, this is an episode that features three variations on the “great man” speech, so it’s not like it isn’t apt.

There’s also the matter of a “twin” to consider. While Millais was painting Ophelia in Surrey, William Hunt was working nearby, apparently in close collaboration, on The Hireling Shepherd. The painting was alternatively derided as too vulgar, or praised for being so socially realistic, but Hunt insisted that the painting had a hidden meaning to it. There’s certainly a religious allegory, but also there’s the matter of the Shepherd holding a Death’s Head Moth in his hand while he seduces the young maiden while his flock wanders off. This actually kind of ties into Jack, who’s off chasing his passion while people are stealing water and not actually being focused on forming a community. Regardless, it’s meant to be read at more than one level — not just the “story” presented, but also the “discourse” that comes from literary and symbolic awareness.

Getting back to Ophelia, though, there’s the matter of what it references as well, mainly Hamlet. There’s a richness to exploring a juxtaposition of Hamlet with Jack at this stage in the game. Hamlet, of course, sees visions of his dead father, just like Jack; they both grapple with melancholy and insanity. And they face a similar problem, the choice to step into the people they can be, or to step away from the responsibilities and opportunities that await them. Hamlet is notoriously reluctant; here, too, is Jack.

There’s another element to Hamlet that’s worth attending to, however, which is the nature of how Hamlet unfolds throughout the ages. It’s a story that’s been rewritten. From 1603 to 1623 we find several extant copies which are not identical. Each version contains something unique. In other words, there are iterations of Hamlet. They follow the same path, more or less, but the words keep changing. And so the inflection changes. Many editors have tried to weave the different versions together into something “authentic.” Consider, then, how production on LOST proceeds – a scene is shot from many different angles, so many different takes, which are then placed together, like a mosaic.

Which is not how television always used to operate. It actually began as something like theatre, but with a camera pointed at it. Take The Carol Burnett Show, for example, since Jack’s father bothered to invoke it. A long-running, award-winning comedy/variety show in the 70s, the show was basically a series of skits performed on a single set in front of a studio audience with a mulitcamera setup, typical of sitcoms back in the day. As a variety show, Carol Burnett isn’t unlike LOST in that it can play with a number of different genres, though more limited – mostly comedy, with a few dance and music numbers.

Which is not how television always used to operate. It actually began as something like theatre, but with a camera pointed at it. Take The Carol Burnett Show, for example, since Jack’s father bothered to invoke it. A long-running, award-winning comedy/variety show in the 70s, the show was basically a series of skits performed on a single set in front of a studio audience with a mulitcamera setup, typical of sitcoms back in the day. As a variety show, Carol Burnett isn’t unlike LOST in that it can play with a number of different genres, though more limited – mostly comedy, with a few dance and music numbers.

And like most sketch comedies, there’s a regular set of recurring characters, played by Burnett, her protégé Vicki Lawrence, Harvey Korman, and Tim Conway. Much of the humor comes with a huge dose of surreal, absurd, and ironic twists, but much of it is actually character-based, especially given how much we come to know the recurring characters. Well, and the actors. Tim Conway, for example, was always adlibbing, particularly with Korman, for the twin purpose of being funnier, and getting Korman to break character and crack up during taping.

Another interesting irony is The Family. Here we’ve got Burnett and Korman playing daughter and son-in-law to Lawrence’s domineering “Momma,” but this is of course an ironic reversal of the relationship of the performers – Lawrence actually being the youngest of the bunch, taken under Burnett’s wing and shown the ropes. (This recurring sketch ending up as a spinoff, “Momma’s Family,” which ran for several years after Burnett ended.)

Part of the fun, then, is seeing the performers playing against the obvious aspects of their types. This requires seeing the show with two different lenses, so to speak – one that’s following the “story” being presented (a less fancy word for “diegesis”) and another that’s paying attention to the “discourse,” a lense of which is inherently aware of the fictionality involved, what goes into the production, and so forth. And Carol Burnett is certainly a self-aware production – hell, the opening of the show typically began with Burnett answering questions from the audience, and doing her best to ad-lib something funny out of it, all while being supremely gracious. This is unusual in film and television – to actually be in a kind of conversation with the audience. But then, Carol Burnett is really theatre that’s been televised.

Part 2 of the essay is coming tomorrow. 🙂

December 8, 2015 @ 10:53 am

“What he’s talking about is the ability to let go. Letting go is what it takes.” <—- Oooh, chills.

“So I’m going to go out on a limb here and say that Water in LOST is symbolic of faith. Let’s see where that gets us.” <—- “Now you’re like me” 🙂

Great point, too, about Christian first being seen standing in water. Of COURSE that’s what he’s helping Jack find.

On a totally unrelated note, here’s something that always frustrates me about the Lost detractors who were mainly disappointed in the show for not upholding its supposed hard SF aesthetic. I think it’s perfectly fair to critique the show on other grounds, but here’s Locke in episode 5 talking about magic and an inherently meaningful (and meaning-full) universe. To me, this was always a clear indication of where the show falls on the SF/F scale.

Looking forward to part 2!

December 13, 2015 @ 9:23 am

it is good post . when i pondered a notion, of which possibly doesn’t entirely hold up but will then have something during it, related to them In the same way corresponding in order to a good rather American set in connection with archetypal poles linked to narrative geography. essay editing service

February 25, 2016 @ 7:04 am

Steps for a Livestock Farmer to Get Started In Raising Rabbits and Chickens for Meat real essay writing help bestessaywriting.com at an affordable price

May 7, 2016 @ 10:33 am

good Google

May 26, 2016 @ 6:29 am

google

January 15, 2017 @ 9:06 am

moviestarplanet is an amazing game. You can spent lot of time on this game. We are here provide you msp free without any technical knowledge. You can easily add the diamond and starcoin to you game account.

May 20, 2019 @ 7:12 am

It is right to submit. Once I pondered a notion, of which likely would not completely maintain up but will then have something in the course of it, related to them inside the equal manner corresponding so one can a terrific as an alternative American set in connection with archetypal poles linked to narrative geography. Visit and review the top essay writing services in UK.

October 9, 2019 @ 8:57 am

I have loved this movie since childhood. An interesting story about those who are in trouble.

I want to see it again. Now I will write an essay I will use the site https://exclusive-paper.net/ and I will watch.

December 4, 2019 @ 5:35 am

Nuts and seeds contain high levels of minerals and healthy fats. Although these are common additions on superfood lists, the downside is that they are high in calories. Portion control is key. Shelled nuts and seeds, in this regard, are ideal because they take time to crack open and slow you down. A quick handful of shelled nuts could contain more than 100 calories, according to Hyde. [Related: Reality Check: 5 Risks of Raw Vegan Diet]

Kale

April 21, 2020 @ 5:23 pm

Amazing! Looking forward to some sketch comedies to brighten the planet.

https://treeservicerichmondhill.com

October 15, 2020 @ 9:43 am

Hi. My dream is travelling. But now I’m a student and I don’t always have time to fulfil my dream. I’m always overloaded with writing tasks. That’s why I sometimes use the help of writing agency. If to speak about nursing writing services, I found the one with is really helpful. These guys are the best.