Lost Exegesis (White Rabbit) — Part 2

Part 1 of the essay can be found here. Unlike that part, this one will have spoilers of future episodes.

Alice in Wonderland

Next up in the Intermission is Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland, written by Lewis Carroll, and directly referred to in the dialogue and as well as being referenced by the episode’s title. Before we examine the manner of the title’s use, let’s take a brief look at Alice. Her adventures cover two books (the other being Through the Looking Glass) and are often issued as a twinset. LOST will certainly play with the Alice story in future episodes – the Season Three finale is titled after the second book, and Jack will read from the “Pool of Tears” chapter in Season Four.

Alice is ostensibly a children’s fairy tale ruled primarily an aesthetic, one that’s largely surreal and operates according to dream logic, what with all the talking animals and such. But the aesthetic is not completely arbitrary – rather, it relies primarily on finding new and strange meaning within the familiar, and in teasing out and secondary meanings for words that it can muster. The famous Jabberwocky poem, for example, is loaded with new portmanteau words, but they’re not meaningless words – rather, they are hybrids, and only sound unfamiliar until you examine the constituent components. There’s likewise a good deal of wordplay – “lessons” become “lessens” which means each teaching gets shorter – while other concepts presented are simply reversals of what we’d expect, like remembering the future instead of the past. And yet the Alice stories aren’t bereft of social commentary. Especially the first book, which presents all manner of British cultural institutions as being faintly ridiculous, albeit heavily disguised in certain aesthetic codes.

And not only does Alice function as cultural commentary, it’s become a part of western culture itself. In his introduction to the year 2000 reprinting, science writer Martin Gardner says that he would not “consider a person educated” who has never read the books. Indeed, that a phrase like “the White Rabbit” can be part and parcel of our regular lexicon attests to that.

So this is where we get the title to this episode, which is directly invoked by John Locke: Jack is chasing his “white rabbit” just like Alice chased a white rabbit into a strange and magical place. Which, of course, suggests that the Island is a kind of “wonderland” and that it operates by different rules than the mundane world. This usage, however, has definitely become mundane in SF/F culture. In the Star Trek episode “Shore Leave,” for example, Dr. McCoy sees a White Rabbit (crafted much like the original illustration of John Tenniel in Carroll’s book) passing by shortly after transporting down to a new planet, which turns out to be an elaborate amusement park. The interactions that the various crewmembers have on the planet are derived from their subconscious, and that is likely a clue to understanding the nature of the Island.

Or perhaps we should consider The Matrix, where Neo follows “the White Rabbit” (this time a tattoo on one of his clients) to meet Trinity, and eventually Morpheus, who describes the experience of leaving the Matrix in Wonderland terms. Interestingly, though, it’s the “real world” that’s a Wonderland, not the false reality of the Matrix. Well, except it isn’t, because The Matrix is a fiction, where “the real world” is actually a metaphor for our own reality. Again, food for thought when it comes to understanding The Island. And indeed, anytime a work of surreal fiction like Alice becomes a way to make sense of another fiction, let alone reality, well, that is quite the rabbit hole, isn’t it?

Watership Down

So, here’s another minor spoiler – the book Watership Down appears in four consecutive episodes of LOST, beginning with White Rabbit. As such, we’ll be looking at Watership Down for the next four essays, this one included, which is appropriate, given that Watership Down is a book about bunnies.

Thankfully, the book is divided into four parts, so we can cover one part per episode. The first part is called “The Journey,” and details the exodus of a group of rabbits from their home, Sandleford Warren, at the behest of a young rabbit named Fiver, who’s been beset with terrible visions. (Slight digression – “Sandleford” and our host’s name, “Sandifer,” share the exact same etymology, which basically refers to a sandbar that bridges a river.) In the audience superior position, we can easily believe Fiver, because we know in a way the rabbits cannot that the warren’s area is going to be bulldozed for new construction — we can read the sign.

Fiver’s brother Hazel is their leader. The two make a matched set – Fiver is the dreaming intuitive, while Hazel is “objective” and “rational,” yet still a believer in Fiver’s visions. It’s Hazel who gets the other rabbits out of Sandleford and over a river, though not quite to safety. Hazel’s interesting. He’s not the smartest rabbit – that would be Blackberry. He’s not the strongest – that’s Bigwig. He’s not the most gifted with words – Dandelion is their storyteller. Obviously, he doesn’t have prophetic visions. Nor is he particularly wise: the climax of the first part is the discovery that the new warren he’s led his friends to is actually a bourgeois death trap.

And yet he’s definitely the leader, the one the other rabbits look to. He, of all the rabbits, seems the most able to make choices and follow through on them despite any hardship they may face. Yet he’s able to change his mind when new information becomes available. He understands the strengths and weaknesses of the other rabbits, and how to delegate and direct their talents. He kind of respects everybody. Which rather shows what leadership is really all about.

So obviously Jack and Locke correspond to Hazel and Fiver, but in a peculiar mirror-twin fashion, for while Jack is the leader of the Losties and Locke has had his mystical encounter with the Island, Jack too has had visions, and Locke can certainly motivate other people, as he does with Jack in this episode. So, again, it’s not like this is a minor literary reference – Watership Down is very relevant to understanding the character drama unfolding before us. And as we’ll see in future essays, it’s going to be ever more relevant to understanding the nature of the Island.

LOST Through the Looking Glass (White Rabbit)

LOST Through the Looking Glass (White Rabbit)

Now positioned with full foreknowledge of the shape of things to come, let’s take a closer look at the Caves that Jack finds in this episode. There’s a hint that this might not be the ideal place, given that the first “caves” found by Hazel in Watership Down turn out to be a terrible place (the rabbits have grown fat, but only in service to the local farmer who periodically snares them for game), but this is largely a red herring. No, the Caves are more than a rabbit warren, and certainly not the bourgeois rabbit warren of “The Journey” in Watership Down.

Of course we can’t help but compare the Caves to the one that shows up at the end of the series. That other one, we’re not going to look too hard at it right now, but suffice it to say that it’s a mythological place, one best understood in terms of metaphor (since it doesn’t make sense any other way). So too, I think, are the Caves of the first season.

First and foremost, the Caves are laden with symbolism. They are archetypal, being among the original places that human beings lived, and certainly the oldest places on earth where our Art is still extant. Just being a Cave, it provides a passage from the world Above, the world of the living, to the world Below, the Underworld, or Other Side, or even the land of the dead, if you so prefer. And of course this can be interpreted psychologically – the land of the subconscious, inhabited by demons and angels and monsters and ghosts. By virtue of being an opening, then, it also becomes a place of Rebirth upon egress. This is certainly in play when it comes to Jack’s discovery – he’s found water; the Losties will live!  But there’s a drowned doll; some will die. So life and death are conjoined. And it’s here he finds his father’s coffin, but it turns out to be empty, a terrible mystery he can’t comprehend.

But there’s a drowned doll; some will die. So life and death are conjoined. And it’s here he finds his father’s coffin, but it turns out to be empty, a terrible mystery he can’t comprehend.

Caves are also a place of myth and allegory. As an allegory, Plato used it as a way to explain the difference between ignorance and knowledge, with the ignorant likened to living in a cave a seeing only shadows. And consider the Japanese sun goddess Amaterasu, for example, who withdrew from the world (and plunged it into darkness) by retreating into a cave, and was only tricked into emerging when the other gods held a mirror at the cave’s entrance to reflect her brilliant light. Caves, then, are places where the truth is hidden.

As those who’ve been reading the Exegesis are aware, one of the things I study is the use of Reversed Images within the text of LOST. Here, at the Caves, we get a twinset of Reversed Images. They occur as Jack finds the Caves – see how the hand in which he carries the torch changes (along with his shirt pocket), and how the orientation of the drowned doll and its surrounding flora flips between shots. I tell ya, I was looking for these, and at this point I’d practically given up, and then suddenly they were found! I wasn’t expecting them here, but it actually makes sense that it’s here they’d be found. After all, such a quest is surely a matter of faith. And water is a reflective surface, yadda yadda.

So what to make of the Caves symbolism in terms of the show? We know that The Cave of Light in the Finale will be a place of the Divine. But these Caves are plural, and dark. So they’re not that. What we can say, however, is that they’re a kind of axis mundi, a place where opposites meet and become as one. As the reversed images point out, this is a place of both Water and Fire, the Fire brought on a stick by Jack. From a fire consecrated by Jack’s grief for his dead father… by his tears… and of course it’s his Father that led him here. If we consider Jack’s father to be symbolic of God (his name is Christian, for Christ’s sake) well, it all starts to come together — in terms of the show, at least. In terms of a spiritual journey.

(That Jack finds the Caves with a big stick lit on fire also makes sense of the dialogue between Sawyer and Shannon, the business about “light sticks” while he’s reading Watership Down, a book which at this point is also about finding a good place in the earth to live. Also, Charlie suggests they use a dowsing rod to find water. Sticks, in service to both the Light and the Water. The union of opposites within a Pole.)

The Axis Mundi

Given the symbolism of the Caves as a place of Rebirth (it’s where Jack is reborn as a leader, after all) let’s be just a bit crass and look at Claire’s role in White Rabbit. As mentioned before, she’s the Astrology fan who brings up the constellation of Gemini with Kate, and even correctly pegs Kate as a Gemini (unless Kate is lying, but as far as I know we don’t have anything to the  contrary). The look that Kate gives Claire after being offered an Astrology reading is priceless — for someone who wants to maximise their ability to shape the future, anything that remotely represents prophecy is anethema.

contrary). The look that Kate gives Claire after being offered an Astrology reading is priceless — for someone who wants to maximise their ability to shape the future, anything that remotely represents prophecy is anethema.

But there’s another thread to this conversation that we’ve overlooked:

CLAIRE: You haven’t found a hairbrush in there, have you?

KATE: No, sorry.

CLAIRE: I must have looked through twenty suitcases. I can’t find one. It’s weird, right? When you’d think that everyone packs a hairbrush.

Suppose… suppose everything that happens here, happens for a reason. What, then, pray tell, is the reason for an exchange like this? It has nothing to do with the plot, nor with the characterization (like Claire cares about such things? Shannon, maybe, but not Claire). Nor is there a great thematic thread about hair or hairbrushes.

However, the exchange makes perfect sense as a form of lampshading. In terms of production, you can’t really concern yourself too much when it comes to things like the “continuity” of hairstyling for the cast. You just can’t. You’re not going to fuck around with the hair of your talent for the sake of continuity. But now that we know there’s no hairbrushes on the Island, we don’t have to pay attention to something as banal as hair for clues regarding the show’s mysteries.

Which in itself is a kind of clue. The show teaches us how to watch it. It’s almost quasi-sentient in this respect. What’s funny, though, given foreknowledge, is what happens in the final season regarding hair. On the one hand, we find Claire living in the jungle, gone crazy, and her hair is practically a jungle unto itself. On the other, we see Boy Jacob running through the jungle in a couple different episodes, but in one his hair has been dyed brown. Which might be there as an exception to the rule. But if rules have exceptions, is that not a form of rule itself? Or perhaps what we call an “exception” is really just a union of opposites. Like the union of Life and Death, Fire and Water, at the Caves.

Less inscrutable than the line about hairbrushes is the conversation Claire has with Charlie in the tent:

Less inscrutable than the line about hairbrushes is the conversation Claire has with Charlie in the tent:

CLAIRE: People don’t seem to look me in the eye here. I think I scare them. The baby… It’s like I’m this time bomb of responsibility just waiting to go off.

Two things to note here. First, there’s an invocation of the Eye, which is a significant symbol at this point in the series; this is concurrent with seeing that Charlie (by virtue of actor Dom Monaghan) has a tattoo on his arm that quotes the Beatles: “Living is easy with eyes closed.” So it’s a line that should be paid attention to. Given that, then, the fact that Claire calls herself a “time bomb” is particularly interesting, given the importance of Time on this Island and the fact that it’s much more “relative” than it is in the Ordinary World. We’ll get into more of this when we get to Raised By Another and All the Best Cowboys, and simply declare that this constitutes foreshadowing.

Speaking of time, and in juxtaposition of water (the lack of which is why Claire has ostensibly fainted), I wonder how our symbol-system works here. Mind you, now we know that Claire is also a child of Christian Shepherd, who Jack is searching for out in the jungle, having Flashbacks about when he was searching for their father in Australia. Claire’s going to get sick in a few episodes’ time, and I have a theory about that… let’s see if it makes sense given what we’ve got here.

It is my contention that the Flashbacks are more than just memories. They are events. Specifically, they are time-travel events. And sometimes, I believe, what happens in the Flashback is not original, but a change from what happened before. This power is conferred by the Island. And as long as the person having Flashbacks makes it back to the Island, in order to have those Flashbacks, causality is preserved. But what if you change something that prevents someone else from getting to the Island, who you know is already there?

If Jack found his father in Australia, that might have altered Claire’s trajectory to the Island. Sure, it’s a matter of faith. But their father is named Christian, he stands in the water, and Claire passes out because she’s lacking water… I dunno, it’s a tenuous connection, and I’m not entirely convinced that at this point in the narrative the character biographies were so well developed the writers had realized that Claire and Jack are half-siblings. All that said, it’s still fun to think about.

The Heroic Journey

The Heroic Journey

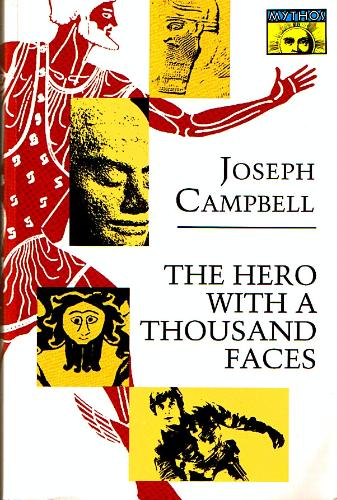

It’s at this point we’ve got to tackle something we’ve been putting off for a while now. That, of course, is Joseph Campbell and The Heroic Journey. But we’ve got to deal with it. After all, we’ll eventually have a monk called Brother Campbell in LOST, not to mention a major DVD extra featurette called “Heroic Journeys.” And the word “hero” has been bandied about a lot already, only five episodes into the run of LOST.

The reason we’ve been putting it off is that much of Campbell and his Journey is rather problematic. As Sandifer has eloquently stated already. For the record, I agree that as a writing template “the heroic journey” is terribly overused now, especially in feature films. And I also agree that Campbell is wrong to paint his work as a “monomyth” or some “master narrative” of mythology.

But I’d be lying if I didn’t find an incredible amount of value in Campbell’s work, especially when it comes to understanding mythology, especially the western mythology in which I, as a westerner, have been steeped for nearly all my life.

And just so y’alls know, it’s not like I was raised a Christian. (I’ve been assaulted for not being Christian, but that’s another story.) I wasn’t raised in any particular religious tradition – my Dad’s a devout atheist, and my Mom is a noncommittal agnostic on account of not having any religious experiences despite her desires. I know I believed in “God” up until about the age of six, when our family went out and failed to procure a lane at the bowling alley; we gave up, and that was that. That I even had such a de-conversion experience is only because my folks put my sister and I in Sunday school at the local Unitarian church for several months in our early childhood, until they decided we were being taught problematic hogwash.

It probably comes as no surprise, then, that spiritual pursuits have been a part of my life since I was a teenager. I’ve explored a number of spiritual traditions, and even practiced a few of them. Practiced to the point where I’d consider myself to have had some rather significant “religious experiences.” And, sure, they could all be in my head (most likely were, yup) but that doesn’t take away from the fact that they were still experiences that I had. And it’s in this respect that Campbell’s work really works for me. The Heroic Journey doesn’t describe all mythologies across the world, it’s not a monomyth, but it sure does make for a hell of a useful framework for understanding a westerner’s spiritual quest.

So, for all eleven of you not yet familiar with the Heroic Journey structure, it basically goes like this: first, there’s a Call to Adventure, which a Hero is often Reluctant to follow. But it is nonetheless followed, often at the heed of a Mentor (if not Supernatural Aid) and motivated by the needs of the Ordinary World. This brings the hero to the Threshold of a “Special Place” which requires a metaphoric Death and Rebirth to enter (which Campbell calls “The Belly of the Whale”). All of this is called “The Departure” (just like the first part of that book about bunnies).

Next comes an “Initiation.” In the Special Place, the hero has many trials to overcome. There may be Temptations. There may be a Mother figure who is likened to a Goddess, and a first taste of the Divine, of supreme comfort and goodness. There’s also the confrontation with the Father – which Campbell calls “Atonement” with the attendant wordplay of “at-one-ment,” for this an encounter where the hero learns to accept the darkness of power and which is ultimately necessary for overcoming the duality of good and evil. All this work leads to Apotheosis, a quintessential religious experience, whereby a Boon is secured (often from some Inner Sanctum, like a Cave) that can be brought back to the Ordinary World.

The third part of this journey is called “The Return.” The hero is chased by Threshold Guardians – one isn’t supposed to steal from the Special Place. Often the hero needs help from the Ordinary World to escape (think Han Solo flying in to throw off Darth Vader as Luke tries to blow up the Death Star). But once back in the Ordinary World, the work is not yet complete – now the hero must become a “Master of Two Worlds,” which amounts to learning how to translate the “gift” of the Special World to the Ordinary Place. Only once the “boon” is finally relinquished is the hero finally off the hook with the “Freedom to Live.”

So, two things to note about Campbell’s structure. First, it’s highly influenced by Jungian psychology, and by the notion of psychological development in general. This isn’t a story about myths, it’s a story about growing up, learning to individuate from mother and father, and to eventually provide constructively towards society – and all within a particularly western paradigm of relationships. Secondly, it also mirrors the “structure of ritual” as described by the anthropologist Arnold van Gennep in his 1909 book, The Rites of Passage, which divides ritual into three parts: Rites of Separation (the Departure), Rites of Change or Liminal Rites (Initiation), and Rites of Incorporation (the Return). We might even put an Alchemical sheen upon this, with the nigredo, albedo, and rubedo stages of The Great Work corresponding accordingly.

Moreover, the structure described is a pretty accurate way of compartmentalizing the religious experience. An encounter with the Divine (even if it’s only in your head, and actually an encounter with the Subconscious) necessarily involves departure from the ordinary world and some kind of liminal experience. The bit about integrating that experience afterwards, well, that’s a measure of success or failure in the endeavor. Certainly there’s all kinds of opportunity for failure in that department.

The Boone

The Boone

So let’s now turn our attention to a character we’ve given very little attention to so far: Boone. Only on looking for a screencap for this piece did I find another reversed image, simply of the waves while Jack dives deep looking for someone to save in the cold open. Mirrors, water, yeah.

Anyways, Boone’s last name is interesting, but we’ll get to it in when we get to Hearts and Minds. For now, all we need to know is that his first name definitely conjures up one of Campbell’s major thematic elements, and that the character of Boone himself is, so far, an incompetent failure.

Let’s track Boone’s exploits so far. First, he failed to resuscitate Rose in Pilot Part 1 because he didn’t actually know CPR, despite his so-called lifeguard experience. He thought getting a bunch of pens to perform a tracheotomy would do the trick. He constantly belittles his sister Shannon; when he tells Charlie in Walkabout that the Fish Hunt was a con, it’s not out of concern for Charlie, but to score a point against Shannon. He tries to save Joanna from drowning in this episode, but fails. He tries to prevent a run on the limited water supplies, too, but that backfires as everyone thinks he just stole the water. We have yet to see Boone contribute in a materially positive way for the Losties in any way just yet.

But this is not how Boone sees himself. He sees himself as a Hero. He wants to be the Hero:

BOONE: You think you’re all noble and heroic for coming after me? I was fine! You’re not the only one who knows what to do around here, you know that? I run a business! Who appointed you our savior, huh? What gives you the right—look at me. Hey, I’m talking to you!

This is the objection of Ego. Boone wants to be a Hero because his Ego demands it. But he’s not qualified; he doesn’t have training. As if “running a business” were enough! And so he fails, constantly. And when someone else is successful, even to the point of saving Boone’s life, his response is not one of gratitude or recognition of materially beneficial skills, but the teenaged sulking of a bruised ego.

It is highly ironic, then, that this character is named Boone.

So with this association in mind, let us attend to the “heroic journey” structure that’s permeated the first few episodes of LOST already. Because these journeys have all been marked by Failure. For example, in Pilot Part 1 we see Jack, Kate, and Charlie head off to the cockpit to retrieve the plane’s transceiver. The Jungle is the Special Place, while the beach is the Ordinary World. The transceiver is the supposed “boon” that will get everyone rescued. But the transceiver doesn’t work. The boon is faulty.

In Pilot Part 2 the Journey is up a mountain, in search of enough “bars” to use the transceiver. Again, the journey fails. The transceiver doesn’t work because it is blocked by another signal, a signal that promises only death and abandonment on this Island. And this information is deliberately withheld from the Ordinary World – there is no integration. We can say the same about “saving” the Marshall, who is secreted away in the Inner Sanctum of Jack’s tent. The first Heroic Journey that’s actually successful is Locke’s: he returns with boar meat. He, in turn, becomes the Mentor to help Jack.

White Rabbit begins with an ironic Heroic Journey. Jack heeds the Call to Adventure, to swim out into the ocean to save Joanna. Jack fails. And yet, he returns with a Boone. Which is to say, he returns with something he did not set out to find. This is a synecdoche for the entire episode. Jack’s journey to find his father in Australia ends in failure; he only find a corpse. He finds death. This is mirror-twinned on the Island. Consider the people on the beach, in the Ordinary World: they need water, and they need a leader. But Jack doesn’t head out into the jungle to find water, or to find a leader. The call he’s answering, the white rabbit he’s following, is that of his father. Which he doesn’t find, doesn’t bring back. But he brings back two boons. He brings back the knowledge of fresh water. And he brings back himself, ready to lead.

Jack, then, is a Boon he brings back from his Heroic Journey. Which he wasn’t expecting at all.

I love this show.

December 9, 2015 @ 1:38 am

And just to kind of set this part apart from the first part, I’ll go ahead and offer up a question to readers: What was it that first drew you into LOST in the first place?

For me it was a combination of the emotional payoff of Walkabout, that moment in Numbers when I realized that all the Numbers (especially 23) had been seeded in the program. That this was a show that also functioned as a sort of puzzle box to try and solve? Oh yeah, I was all over it like cheese on pizza.

And then I got deeply invested in the characters — Charlie, Claire, and Hurley in particular, with a nice dose of Locke. They all had journeys that I could relate to, if only at a metaphoric level. But that’s what mythology is all about, really, I think.

So how about you? What got you hooked?

December 9, 2015 @ 10:45 am

I love this show, too. These posts are great. I always felt the thematic and symbolic cohesion of the show, even as others complained about the lack of cohesion on a purely surface or narrative level (although even there I think it’s far better than its reputation). Some of the connections you mention are things I’ve caught previously, but many are not, if only because I haven’t taken the time to go through it with the fine-tooth come you are. I look forward to these posts every time, and you’re not disappointing.

What drew me to LOST? At first, Dominic Monaghan, coming over from LOTR fandom. After that, the previews for the Pilot – the show looked like such an epic adventure, unlike anything I’d ever seen on TV (I was primarily a sitcom watcher before LOST and the era of “peak TV” changed everything).

The Pilot episodes themselves certainly impressed me, and I grew more and more in love with the show with each new episode of that unparalleled first season.

I think my real conversion experience was Walkabout, but not in the way you’d expect. I do remember the shock and wonder of Walkabout’s ending, but strangely my most vivid memory of realizing how emotionally invested I was was at the end of Tabula Rasa when Kate offers to tell Jack what she did and he declines. I remember feeling such disappointment, and was seriously worried that the Flashback structure would only be for that one episode. I was so elated to find at the BEGINNING of Walkabout that no, this would continue to be the structure of the series. So, I think it was that: The dual Island/Flashback structure, and the paralleled journeys of the exploring the Island and exploring the characters. Seeing the mysteries of both unfold together, and how each aspect of the show echoed and spoke to the other across time and space… yeah, that was my sweet spot.

December 9, 2015 @ 3:21 pm

There’s a little bit of sleight of hand about the seeding of the numbers, I believe. Once they came up with the concept, they looked for numbers which had already appeared in the show, like Kate’s reward, then used those in the list.

December 9, 2015 @ 4:29 pm

23 was always one of the numbers, for the esoteric reasons cited in the comments in previous essays. It’s a number that catches the attention of certain people.

So it’s no coincidence that 23 is the row Jack sits in for the Pilot episode.

December 9, 2015 @ 8:47 am

What got me hooked on LOST? I think it might be this post. I confess I gave up on the show round about the third season but, inspired by this blog, I fully intend to revisit the island.

You got me with the Alice stuff. The works of Lewis Carroll are a slight obsession of mine. I recently attended an event at the British Library, a celebration of the 150th anniversary of the first publication of Alice in Wonderland. The panel of writers included the great granddaughter of the original Alice and Frank Cotrell-Boyce (familiar to followers of the Eruditorum of course as the writer of In the Forest of the Night) who memorably described Alice in Wonderland as ‘a book full of memes’. A work that has transcended literature to become an indelible part of Western culture both for its instantly recognisable imagery and its verbal coinages.

Apart from Charles Dodgson (Lewis Carroll) another classic children’s author comes to mind when contemplating LOST – JM Barrie. In Peter Pan of course we have not only a magical island (Neverland) but the Lost Boys. Barrie also wrote a stage play which concerned itself with supernatural disappearances called Mary Rose or The Island That Likes To Be Visited.

December 9, 2015 @ 4:31 pm

I hope you listened to the Alice in Wonderland Shabcast this past spring!

December 10, 2015 @ 4:22 pm

I certainly did, enjoyed it immensely and commented as such. The Jonathan Miller BBC adaptation of Alice is so extraordinary for a number of reasons. Not least for its inspired casting and the use of Ravi Shankar’s evocative sitar music. I was pleased to learn (at the event I mentioned) that it is Cottrell-Boyce’s favourite version too.

December 11, 2015 @ 3:23 pm

What got me into LOST? Nothing yet – still never seen it – but I admit posts like these are tempting me!

Another Carroll fan here, BTW – I once wrote a rather verbose page on adapting Through the Looking Glass as a text adventure (or work of Interactive Fiction, if you prefer).

December 9, 2015 @ 10:50 am

“Time bomb” sounds rather like Jughead.

Sawyer reading Watership Down – One of the best and most unexpected character notes was realizing that redneck Sawyer is the bookworm.

Fantastic connection with Boone’s name, and Jack coming back with “boons.” I like the idea of Boone being symbolic of the failures of the hero’s journey, even as he enables other people to achieve their journeys in unexpected ways. We’ll definitely have to come back to that in Deus Ex Machina.