Sex in the Time of Empire

I was a guest on Daniel & Shana’s Oi! Spaceman podcast again, this time talking about ‘Rose’ and ‘The End of the World’. But now, back to the ongoing saga…

I was a guest on Daniel & Shana’s Oi! Spaceman podcast again, this time talking about ‘Rose’ and ‘The End of the World’. But now, back to the ongoing saga…

The last time I wrote about Star Wars, I said that it sees the galactic politics and history it depicts as being essentially powered by neurosis, specifically male neurosis. Rogue One very explicitly adheres to this pattern – though, laudably, it represents a counter-strain in opposition.

In Rogue One, the Death Star openly represents the immense strength and immense vulnerability of any imperial system, the simultaneously terrifying and ridiculous urges and principles which animate such systems. At a different-yet-connected level, it represents the same mixture of dangerous power and ridiculous vulnerability within one of the techno-bureaucrats who run that system. It sees the causal throughline as very clearly running from inside the heads of at least two men, out into the universe.

I have mixed feelings about this. The thesis that politics comes from emotions and psychology, though I believe it is ultimately wrong, doesn’t necessarily have to collapse into a reactionary ‘fix yourself first’ ideology. Psychology clearly plays a role in politics, and in resistance and struggle. The subjective factor is important. We are generally supposed to think that the ‘mass psychology of crowds’ is negative and scary, but crowds can also be expressions of unifying principles rather than just the loss of individuality, and collective struggles create dialectics of learning and cooperation that expand people’s political horizons. This is why it is generally a mistake to too ruthlessly criticise mass political movements that, while broadly on the right side, also have imperfect or even pernicious elements. A lot of people who demonstrate against Trump will have ideas that are retrograde, unpleasant, unhelpful, conventional, short-sighted… but they’re still better than anyone else because they’re there, on the street. And the collective process of protest creates a space – found nowhere else within capitalism – in which people can encounter strange new people, and strange new ideas, face to face as it were, in struggle, in unity but not in conformity, where they can learn and grow and expand, can improve their political consciousness. The social effect of mutual support and solidarity in struggle is a vital part of any radical movement. This is undoubtedly psychological. Indeed, it is only the vulgar reduction of psychology, society, etc into discrete and separate things (itself an aspect of bourgeois ideology) which sees the psychological aspect as being apart from the other dynamics of political struggle. Anything that impedes this dialectic is to be shunned, including criticism that stops being constructive and becomes sectarian doctrinaire nitpicking, whether it comes from identity politics or from class politics. (Again, the apparent schism is a false dichotomy.)

On the other hand, the way Rogue One – and Star Wars generally – depicts cosmic levels of political tyranny and turmoil as emanating directly from inside addled and repressed and anxious male brains can be, as it were, reclaimed. It needn’t reduce the political to the personal so much as remind us that all these structures are, ultimately, human creations, and as such they are structured like us, as are all things we create, as are our children. And while I reject the ‘King List’ version of history – the idea that history is ultimately the result of the ideas and actions of ‘great men’ – there is doubtless a sense in which the grotesque imbalances of class society make the individual neuroses of certain individuals far more damaging to the rest of us than they should be. I’m sure I could think of applications of this idea to present-day political events, if I were to make a special effort.

Rogue One is a deeply political film, but it shows every political decision made by the m ain characters underwritten by essentially personal motivations. It would not be fair or accurate, however, to say that these personal motivations are always apolitical or unpolitical. Apart from anything else, I reject any theory of human consciousness which sees humans as essentially isolated individuals staring out at the world through two peepholes. Human consciousness is socially constructed. Every individual is the shifting and temporary arrangement of interrelations between a self and a society. Self and world, self and society, are interpenetrating. The self is really nothing more than a way of looking at a particular bit of the world. That doesn’t make it unreal, but it does – contra bourgeois ideology – make it untenable as a sovereign and supreme subject. We are far more socially constructed than popular bourgeois ideology would have us believe, and this makes us more free rather than less, because freedom is social too, not individual as capitalism always claims. So I don’t really believe that there are such things as apolitical or unpolitical emotions at all. However, it is possible to designate an emotion or motivation as apolitical or unpolitical in a temporary and local sense, depending on one’s chosen and temporary working definition of politics in any given situation. In some texts, the personal motivations of the characters are carefully segregated from politics. But I don’t think Rogue One does this.

For instance, it is very hard to see Krennic’s internalised, denied, curdled, possibly-unconscious attraction to Galen as unpolitical or apolitical in the context of the Empire. There is no explicit homophobia in the Empire, but I can’t imagine a whisper of such things would do a man’s career any good.

Just as the Empire is inherently human, and largely white and/or Western, so it is inherently… well, not straight exactly, but rather sexless. Mind you, its depiction as sexless on screen is to do with ‘real world’ factors such as the overall sexlessness of the series, designed as it was for children.

It’s worth asking – given that sexuality is such a huge part of human psychology, and given that we are opaque to ourselves and not in control of our unconscious drives, and given that almost all children’s stories are written by adults, and given that the modern practice in children’s stories is to edit out sexuality to a great degree… where does the sexuality go? If we don’t believe that sexuality, or indeed any part of the human psyche, sits in a mental box that we can choose to keep open or closed, then we should probably assume that sexuality gets into children’s stories written by adults. When it is consciously edited out, it manifests itself unconsciously. It is sublimated, and reconfigured into other forms. And indeed, anyone who knows children’s stories know this. Classic fairytales are dripping with sublimated sex, as are many modern children’s stories, particularly more elaborate ones for older children.

Sex generally only factors into the series in the abstract and distanced form of family relationships. The relationship between Anakin and Padme in the prequels should, on the surface, be the sexiest the series ever got… but that isn’t exactly how it pans out on screen. It’s noticeable that, like almost every couple of failed-couple in the Harry Potter series, Anakin and Padme meet first when they are children. (Natalie Portman was actually 18 when she starred in Episode One, but her character is depicted in highly childlike ways.) In practice, Anakin and Padme spend very little time doing anything sexy. In fact, Padme spends very little time doing anything, and they spend very little time together overall. Even Leia and Han’s ‘romance’ in Empire and Jedi consists of a couple of kisses between largely-hostile conversations and lots of running around, being captured, escaping, going on missions, etc. If Leia got it on with Han after rescuing him from Jabba, the film is careful to take us back to Degobah with Luke while this happens, so we can watch a muppet die instead. Meanwhile, the rest of the galaxy seems superficially sexless, apart from Jabba himself, who likes chained semi-naked humanoid slavegirls, despite being a giant slug, which is so incoherent it scrambles the sexual implications until lust itself looks both inherently abusive and inherently… um… what would be the word? Impractical? Let’s go with that.

Jabba, and Jabba’s palace, is one locus of where the adult sexuality – consciously edited out but, of course, uncontainable, goes in the stories. It can’t not get in – because human sexulaity simply doesn’t work like that – so it has to be hidden, so it goes into dark corners and into disguise, is transfigured and reified. One of the tells is the very adolescentness of the Jabba sequences, with their anxious combination of sex, domination, and revulsion. But one reason why the Jabba sequences don’t work so well in context (despite being, in aspiration, some of the most interesting material in the series) is because they’re too open about containing sublimated sexuality.

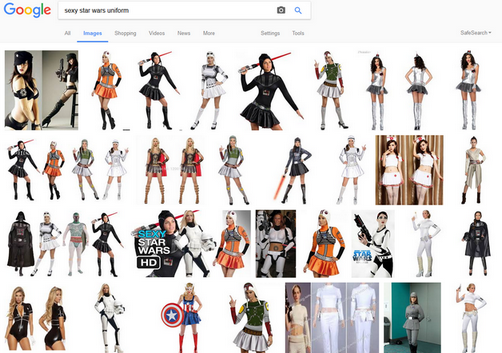

Meanwhile, the films’ most powerful sequences tend to work precisely because they sublimate the sexuality more completely. Part of the thrill of the Empire is in its combination of orderliness and opulence, coldness and pageantry, blankness and texture, functionality and fetishism. The Empire is gorgeous to look at in a way that the Rebellion simply isn’t. It’s no accident that assorted Rebel characters suddenly look a lot sexier when they steal and don imperial uniforms. We know about the libidinous charge of the uniform, generally. There is no uniform that is not fetishised by human beings, not even the SS uniform. And indeed, it is almost certainly putting the cart before the horse to suggest that uniforms are only fetishised later, as an afterthought. (I wanted to include some theory from sex theorists here, but you try researching this topic on Google.)

Krennic’s sublimated attraction to Galen exists in the context of an imperial culture that is intensely male and homosocial, and dripping with repurposed and furtive glamour, and as repressed as it is oppressive. Moreover, it occurs in the contest of the Empire’s inhuman repurposing and utilisation of all human creativity. The sexual spark that is poured furtively into the Empire’s aesthetically controlled-yet-gorgeous evil becomes a symbol of the way structures like the Empire simultaneously repress human creativity and also fuel themselves on that very repression.

Orwell pointed out in Nineteen Eighty-Four how totalitarianism (not a term I’m fond of, but let’s cope) channels sexual energies into frenzied hate directed towards designated enemies of the state, foreign and domestic. The impersonality of the hate can be seen in the way it can be directed towards one object one minute, and then immediately redirected towards another object the next minute, without a moment’s pause or disorientation. I have to say, I don’t think this sort of thing is the fundamental animating principle of tyranny, but it is certainly a technique in the social construction and maintenance of tyranny. Political structures find and utilise existing human psychological realities, and construct themselves along those lines. How could they do otherwise, being themselves human creations? In the process, they interpenetrate with human psychological realities, affecting them in return. In class society, this is a form of alienation. It is by no means unique to authoritarian regimes, but it is generally a feature of hierarchical societies. In such societies it can be directed towards foreign competitors, and in the age of empire it forms part of the psychological animus of supremacism, racial or cultural. Look how easy it is for centrist liberals, working within the ideological mainstream, to instantly, without any consciousness of being directed, channel alarming degrees of frothing moral urgency and outrage towards whatever designated enemy or crisis currently best serves the needs of established power. It’s sometimes forgotten these days that liberals were yelling bellicose cries of “Benghazi!” before conservatives turned that word into a conspiracy theory. Western culture is still imperial. It still channels alienated human creativity – some of it undoubtedly sexual, though I wouldn’t want to enthrone sexual energy too much; it’s hardly the only or necessarily the most crucial energy – towards the needs of power.

What we end up with is, of course, the old question of the relation between structure and agency in history. But we also end up with the old question of the relation between structure and agency inside the human mind. These are actually questions which Star Wars tries to grapple with. Indeed, once again, while the series as a whole tends to do so implicitly, Rogue One tends to make it far more aesthetically explicit. It relies upon the idea that the galaxy is structured fractally, with each instantiation of structure existing within a larger instantiation of the same structure, and with smaller instantiations of the same structure within it in turn.

But we’ll get to that.

March 25, 2017 @ 2:53 am

I know somebody who started an incredibly successful Star Wars burlesque franchise, The Empire Strips Back.

March 25, 2017 @ 9:33 am

Those recruitment posters with pin-ups in Stormtrooper armor are another epiphenomenon of this kind.

March 25, 2017 @ 11:45 am

Well, now you’ve mentioned it, it’s a little weird that Leia says Luke’s too short to be a Stormtrooper when he rescues her, and yet his uniform seems to fit him pretty fucking perfectly. Or that he and Han don’t have helmet-hair when they take their helmets off.

March 25, 2017 @ 5:52 pm

My theory: smart armour. It restructures itself to fit the person wearing it.

I’m still working on why an army with strict height regulations/all identically sized clones would have such a thing, though…

March 25, 2017 @ 7:55 pm

The Stormtrooper armor fits Han and Luke so well because Han and Luke are, unbeknown to them, rogue clones from the imperial hatcheries. Under the helmets, every single Stormtrooper in the original trilogy looks like either Han or Luke. This is because all Stormtroopers are grown from the DNA of Anakin Skywalker and Padme Amidala. Vader did this to make himself feel better. This, of course, means that Han and Luke are actually brothers, Which means Leia is Han’s sister too. Which might explain why Ben Solo came out so unstable.