Build High for Happiness 5: Crash (1973/1996)

a fixed spatial field entails establishing bases and calculating directions of penetration

a fixed spatial field entails establishing bases and calculating directions of penetration

Within the biotemporal omnipresence of the hypercube escape must be understood as an exit wound. In practice, this would manifest itself as an area towards which the natural flows towards annihilation congregate – the eddies along the surface where narrative tracks converge, scar tissue forming anticipatorily around the site of injury. Counterintuitively, then, a weak point is going to appear as the thickest part of the skin.

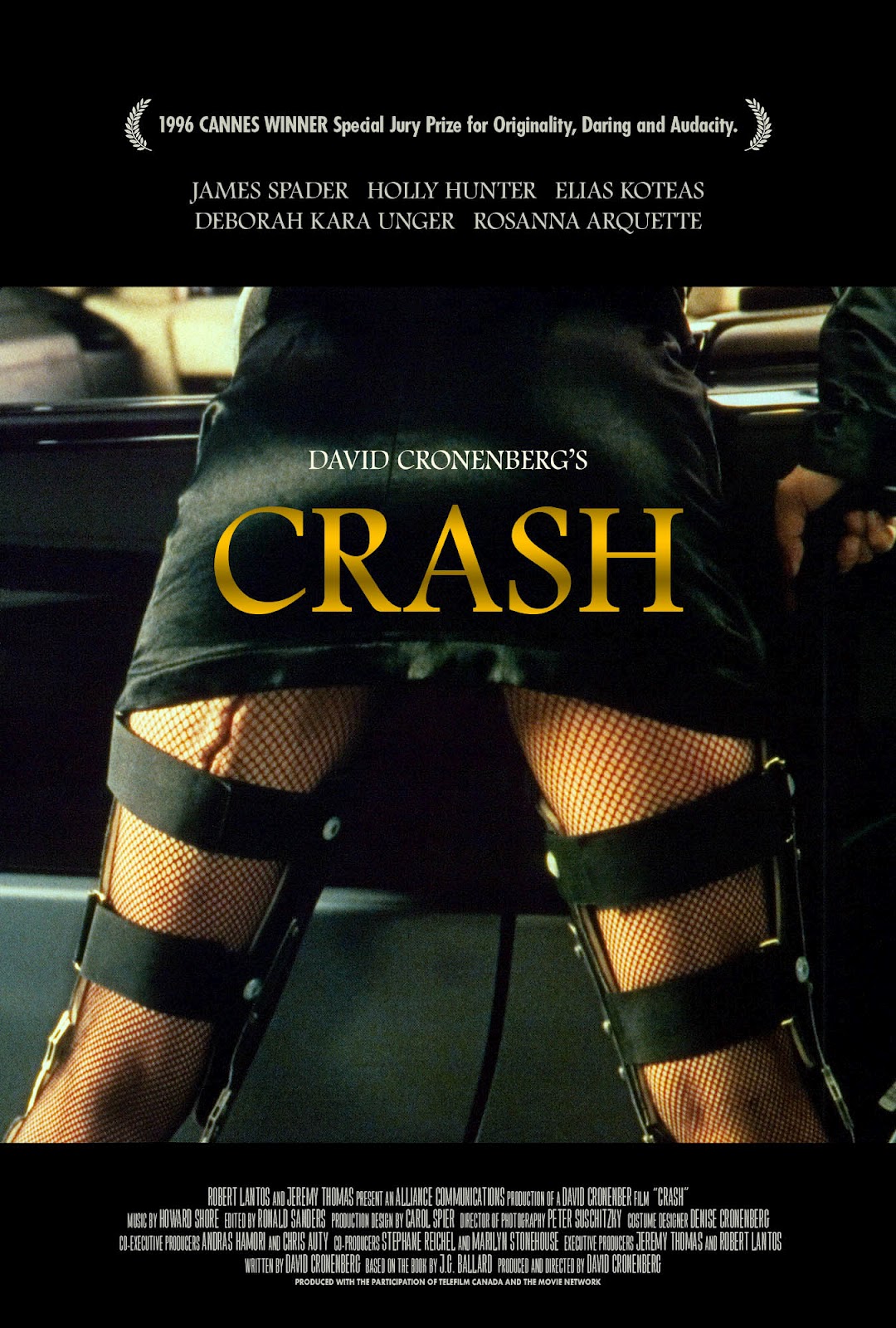

Crash, then – first of Ballard’s three attempts at sci-fi without futurity, the book is a famously scandalous meditation on the eroticism of the car crash. Its film adaptation, in 1996, is suspended neatly at the halfway point between the twin towers of the Ballard and Wheatley/Jump High-Rises, and circles neatly around other touchstones. It’s directed by David Cronenberg, for instance, whose 1975 film Shivers saw him independently arriving at the concept of a modernist apartment complex descending into madness, albeit because of genetically engineered parasites who drive their hosts mad with lust as opposed to because of some inherent property of modernity. Its opening sequence – a slow tracking shot through an aircraft hanger, across the sleek bodies of airplanes, fragmented like a female body beneath the male gaze, until finally, in the middle distance, a woman undressing enters the frame and, as we move to close-up, exposes her nipple and lays it seductively upon the body of the aircraft, which she proceeds to relate to more closely and intimately than the lover who subsequently takes her from behind – draws a crucial link between the sexuality of cars and one of Le Corbusier’s other defining aesthetic obsessions, the airplane.

This connection is more subdued in the novel, but still present: Ballard’s wife (the main character is named after himself) is sleeping with a pilot and taking flying lessons, and Ballard has occasional descriptions like “even the giant aircraft taking off from the airport were systems of excitement and eroticism, punishment and desire waiting to be inflicted on my body.” The connection between cars and planes is hardly an unexpected one requiring reference to Le Corbusier, but the link is nevertheless generative. Le Corubusier’s aestheticization of mechanical functionality creates a tightly wound feedback loop that Ballard efficiently short-circuits. As Le Corbusier puts it, talking about cars, “through the relentless competition of the countless firms that build them, each has found itself under obligation to dominate the competition, and, on top of the standard for realized practical things, there has intervened a search for perfection and harmony outside of brute practical fact, a manifestation not only of perfection and harmony, but of beauty.” In other words, the mechanistic efficiency of cars naturally leads to the emergence of beauty, to which Ballard, quite sensibly, sets about trying to fuck.

The cold detachment that characterizes Laing is obviously a big part of this, but what Crash foregrounds that High-Rise does not is the eroticization of this clinicism, as evidenced by his description of a fantasy of “the dying chromium and collapsing bulkheads of their two cars meeting head-on in complex collisions endlessly repeated in slow-motion films, by the identical wounds inflicted on their bodies, by the image of windshield glass frosting around her face as she broke its tinted surface like a death-born Aphrodite, by the compound fractures of their thighs impacted against their handbreake mountings, and above all by the wounds to their genitalia, her uterus pierced by the heraldic beak of the manufacturer’s medallion, his semen emptying across the luminescent dials that registered forever the last temperature and fuel levels of the engine.”…